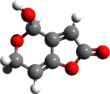

Patulin

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-hydroxy-4H-furo[3,2-c]pyran-2(6H)-one

| |||

| Other names

2-Hydroxy-3,7-dioxabicyclo[4.3.0]nona-5,9-dien-8-one

Clairformin Claviform Expansine Clavacin Clavatin Expansin Gigantin Leucopin Patuline | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.215 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C7H6O4 | |||

| Molar mass | 154.12 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Compact prisms | ||

| Density | 1.52 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | 110 °C (230 °F; 383 K) | ||

| Soluble | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Patulin is an organic compound classified as a polyketide. It is named after the fungus from which it was isolated, Penicillium patulum. It is a white powder soluble in acidic water and in organic solvents. It is a lactone that is heat-stable, so it is not destroyed by pasteurization or thermal denaturation.[2] However, stability following fermentation is lessened.[3] It is a mycotoxin produced by a variety of molds, in particular, Aspergillus and Penicillium and Byssochlamys. Most commonly found in rotting apples, the amount of patulin in apple products is generally viewed as a measure of the quality of the apples used in production. In addition, patulin has been found in other foods such as grains, fruits, and vegetables. Its presence is highly regulated.

Biosynthesis, synthesis, and reactivity

[edit]Patulin is biosynthesized from 6-methylsalicylic acid via multiple chemical transformations.[4]

Isoepoxydon dehydrogenase (IDH) is an important enzyme in the multi-step biosynthesis of patulin. Its gene is present in other fungi that may potentially produce the toxin.[5] It is reactive with sulfur dioxide, so antioxidant and antimicrobial agents may be useful to destroy it.[6] Levels of nitrogen, manganese, and pH as well as abundance of necessary enzymes regulate the biosynthetic pathway of patulin.[5]

Uses

[edit]Patulin was originally used as an antibiotic against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but after several toxicity reports, it is no longer used for that purpose.[7] Isolated by Nancy Atkinson in 1943, it was specifically trialed to be used against the common cold.[7] Patulin is used as a potassium-uptake inhibitor in laboratory applications.[2] Kashif Jilani and co-workers reported that patulin stimulates suicidal erythrocyte death under physiological concentrations.[8]

Sources of exposure

[edit]Frequently, patulin is found in apples and apple products such as juices, jams, and ciders. It has also been detected in other fruits including cherries, blueberries, plums, bananas, strawberries, and grapes.[6] Fungal growth leading to patulin production is most common on damaged fruits.[9] Patulin has also been detected in grains like barley, wheat, corn and their processed products as well as in shellfish.[6][10][full citation needed] Dietary intake of patulin from apple juice has been estimated at between 0.03 and 0.26 μg per kg body weight per day in various age groups and populations.[11] Content of patulin in apple juice is estimated to be less than 10–15 μg/L.[11] A number of studies have looked into comparisons of organic vs conventional harvest of apples and levels of patulin contamination.[12][13][14] For example, one study showed 0.9% of children drinking organic apple juice exceeded the tolerable daily intake (TDI) for patulin.[15][full citation needed] A recent article described detection of patulin in marine strains of Penicillium, indicating a potential risk in shellfish consumption.[10]

Toxicity

[edit]A subacute rodent NOAEL of 43 μg/kg body weight as well as genotoxicity studies were primarily the cause for setting limits for patulin exposure, although a range of other types of toxicity also exist.[3]

While not a particularly potent toxin, patulin is genotoxic. Some theorize that it may be a carcinogen, although animal studies have remained inconclusive.[16] Patulin has shown antimicrobial properties against some microorganisms.[1] Several countries have instituted patulin restrictions in apple products. The World Health Organization recommends a maximum concentration of 50 μg/L in apple juice.[17] In the European Union, the limit is also set at 50 micrograms per kilogram (μg/kg) in apple juice and cider, at 25 μg/kg in solid apple products, and at 10 μg/kg in products for infants and young children. These limits came into force on 1 November 2003.[18][full citation needed]

Acute

[edit]Patulin is toxic primarily through affinity to sulfhydryl groups (SH), which results in inhibition of enzymes. Oral LD50 in rodent models have ranged between 20 and 100 mg/kg.[3] In poultry, the oral LD50 range was reported between 50 and 170 mg/kg.[5] Other routes of exposure are more toxic, yet less likely to occur. Major acute toxicity findings include gastrointestinal problems, neurotoxicity (i.e. convulsions), pulmonary congestion, and edema.[3]

Subacute

[edit]Studies in rats showed decreased weight, and gastric, intestinal, and renal function changes, while repetitive doses lead to neurotoxicity. Reproductive toxicity in males was also reported.[5] A NOAEL in rodents was observed at 43 μg/kg body weight.[3]

Genotoxicity

[edit]WHO concluded that patulin is genotoxic based on variable genotoxicity data, however it is considered a group 3 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) since data was inconclusive.[3]

Reproduction studies

[edit]Patulin decreased sperm count and altered sperm morphology in the rat.[19] Also, it resulted in abortion of F1 litters in rats and mice after i.p. injection.[5] Embryotoxicity and teratogenicity were also reported in chick eggs.[5]

Immunotoxicity

[edit]Patulin was found to be immunotoxic in a number of animal and even human studies. Reduced cytokine secretion, oxidative burst in macrophages, increased splenic T lymphocytes, and increased neutrophil numbers are a few endpoints noticed.[5] However, dietary relevant exposure would not be likely to alter immune response.[6]

Human health

[edit]Although there are only very few reported cases and epidemiological data, the FDA has set an action limit of 50 ppb in cider due to its potential carcinogenicity and other reported adverse effects.[3] In humans, it was tested as an antiviral intranasally for use against the common cold with few significant adverse effects, yet also had negligible or no beneficial effect.[7]

Risk management and regulations

[edit]Patulin exposure can be successfully managed by following good agricultural practices such as removing mold, washing, and not using rotten or damaged apples for baking, canning, or juice production.[3][9]

US

The provisional tolerable daily intake (PTDI) for patulin was set at 0.43 μg/kg body weight by the FDA[3] based on a NOAEL of 0.3 mg/kg body weight per week.[3] Monte Carlo analysis was done on apple juice to compare exposure and the PTDI. Without controls or an action limit, the 90th percentile of consumers would not be above the PTDI. However, the concentration in children 1–2 years old would be three times as high as the PDTI, hence an action limit of 50 μg/kg.[3]

WHO

The World Health Organization recommends a maximum concentration of 50 μg/L in apple juice.[17]

EU

The European Union (EU) has set a maximum limit of 50 μg/kg on fruit juices and drinks, while solid apple products have a limit of 25 μg/kg. For certain foods intended for infants, an even lower limit of 10 μg/kg is observed.

To test for patulin contamination, a variety of methods and sample preparation methods have been employed, including thin layer chromatography (TLC), gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and capillary electrophoresis.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Merck Index, 11th Edition, 7002

- ^ a b Patulin sigmaaldrich.com

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Patulin in Apple Juice, Apple Juice Concentrates and Apple Juice Products". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15.

- ^ Puel, Olivier; Galtier, Pierre; Oswald, Isabelle (2010). "Biosynthesis and Toxicological Effects of Patulin". Toxins. 2 (4): 613–631. doi:10.3390/toxins2040613. PMC 3153204. PMID 22069602.

- ^ a b c d e f g Puel, Olivier; Galtier, Pierre; Oswald, Isabelle P. (5 April 2010). "Biosynthesis and Toxicological Effects of Patulin". Toxins. 2 (4): 613–631. doi:10.3390/toxins2040613. PMC 3153204. PMID 22069602.

- ^ a b c d Llewellyn, G.C; McCay, J.A; Brown, R.D; Musgrove, D.L; Butterworth, L.F; Munson, A.E; White, K.L (1998). "Immunological evaluation of the mycotoxin patulin in female b6C3F1 mice". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 36 (12): 1107–1115. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(98)00084-2. PMID 9862653.

- ^ a b c Medical Research Council. Clinical trial of patulin in the common cold. Lancet1944; ii: 373-5.

- ^ Lupescu, A; Jilani, K; Zbidah, M; Lang, F (2013). "Patulin-induced suicidal erythrocyte death". Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 32 (2): 291–9. doi:10.1159/000354437. PMID 23942252.

- ^ a b "Patulin". Archived from the original on 2013-10-18. Retrieved 2013-11-25.

- ^ a b Pouchous et al. Shellfish

- ^ a b Wouters, FA, and Speijers, GJA. JECFA Monograph on Patulin. World Health Organization Food Additives Series 35 (http://www.inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v26je10.htm)

- ^ Pique, E., et al. Occurrence of patulin in organic and conventional apple juice. Risk Assessment. Recent Advances in Pharmaceutical Sciences, III, 2013: 131–144.

- ^ Piemontese, L.; Solfrizzo, M.; Visconti, A. (2005-05-01). "Occurrence of patulin in conventional and organic fruit products in Italy and subsequent exposure assessment". Food Additives and Contaminants. 22 (5): 437–442. doi:10.1080/02652030500073550. ISSN 0265-203X. PMID 16019815. S2CID 31155096.

- ^ Piqué, E; Vargas-Murga, L; Gómez-Catalán, J; Lapuente, Jd; Llobet, JM (October 2013). "Occurrence of patulin in organic and conventional apple-based food marketed in Catalonia and exposure assessment". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 60: 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.052. PMID 23900007.

- ^ Beark et al 2007

- ^ "Patulin: a Mycotoxin in Apples". Perishables Handling Quarterly (91): 5. August 1997

- ^ a b "Foodborne hazards (World Health Organization". Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ Patulin information leaf from Fermentek

- ^ Selmanoglu, G (2006). "Evaluation of the reproductive toxicity of patulin in growing male rats". Food Chem. Toxicol. 44 (12): 2019–2024. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2006.06.022. PMID 16905234.

- ^ Baert, Katleen; De Meulenaer, Bruno; Verdonck, Frederik; Huybrechts, Inge; De Henauw, Stefaan; Vanrolleghem, Peter A.; Debevere, Johan; Devlieghere, Frank (2007). "Variability and uncertainty assessment of patulin exposure for preschool children in Flanders". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 45 (9): 1745–1751. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2007.03.008. PMID 17459555.

External links

[edit]- Patulin Archived 2017-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, Food Safety Watch