Civic Gospel

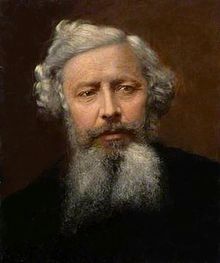

The Civic Gospel was a philosophy of municipal activism and improvement that emerged in Birmingham, England, in the mid-19th century. Tracing its origins to the teaching of independent nonconformist preacher George Dawson,[1] who declared that "a town is a solemn organism through which shall flow, and in which shall be shaped, all the highest, loftiest and truest ends of man's moral nature",[2] it reached its culmination in the mayoralty of Joseph Chamberlain between 1873 and 1876.[3] After Dawson's death in 1876 it was the Congregationalist pastor R. W. Dale who took on the role as the movement's leading nonconformist spokesman.[4] Other major proponents included the Baptist Charles Vince and the Unitarian H. W. Crosskey.[5]

Early years

[edit]During its early years in the 1850s and 1860s the concept of the Civic Gospel combined Dawson's liberal theology with a social and political vision of civic brotherhood that saw a city as having a communal interest that transcended those of its constituent social classes and other groupings.[6] Under Dale it evolved into a more systematic and thorough philosophy, less dependent on Dawson's idiosyncratic theology.[7] In its mature form its position was essentially that a city was a closer and more significant form of community than a nation or a religion, and thus it was a municipality, more than parliament or the church, that had most to contribute to the health, welfare and fairness of urban society.[8]

Participants and achievements

[edit]

Dawson's congregation at the Church of the Saviour included some of the most influential cultural and political leaders of Victorian Birmingham,[9] including not only Joseph Chamberlain, but also George Dixon, J. T. Bunce, J. A. Langford, Robert Martineau, Samuel Timmins, A. F. Osler, Jesse Collings, William Kenrick, and William Harris. Between 1847 and 1867, 17 members of Dawson's congregation were elected to the Town Council, of whom 6 were elected mayor.[10] The philosophy encompassed not only practical measures such as slum clearance and improvements in sanitation, but also the provision of cultural facilities such as libraries and a museum and art gallery: for 31 of the first 33 years of its existence the Birmingham Free Libraries Committee had as its chairman a member of Dawson's congregation.[11] The effect of the Civic Gospel was to transform Birmingham from the inactive and backward municipal borough that had emerged from the Municipal Reform Act of 1835 into a model of progressive, enlightened and efficient local government.[12] Roy Hartnell writes: "It was nothing less than a bloodless revolution which had been engineered from above by the exploiting class, rather than through agitation from below by the exploited class."[13] By 1890, a visiting American journalist could describe Birmingham as "the best-governed city in the world".[14]

Wider influence

[edit]- The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw Birmingham becoming a model of municipal progress in England,[15] with other municipalities, especially those under Nonconformist control, following the lead of its civic gospel. Thus in Lancashire Darwen eagerly adopted such reforms as a free public library, their civic gospel spilling over into moral policing when the leadership attempted to remove light literature from the shelves (the move was swiftly defeated).[16] In London, Nonconformist capture of the London County Council in 1889 led to similar developments in the 1890s,[17] as – alongside municipal libraries, parks, swimming pools and trams – there came a municipal puritanism that restricted licensing hours and controlled music halls.[18]

- Chamberlain's reforms were influential on Beatrice Webb, one of the leaders of the Fabian movement, which laid the foundations of the Labour Party in the United Kingdom. Beatrice Webb's husband, Sidney Webb, wrote in 1890 in Socialism in England:[19]

It is not only in matters of sanitation that this "Municipal Socialism" is progressing. Nearly half the consumers of the Kingdom already consume gas made by themselves as citizens collectively, in 168 different localities, as many as 14 local authorities obtained the power to borrow money to engage in the gas industry in a single year. Water supply is rapidly coming to be universally a matter of public provision, no fewer than 71 separate governing bodies obtaining loans for this purpose in the year 1885–86 alone. The prevailing tendency is for the municipalities to absorb also the tramway industry, 31 localities already owning their own lines, comprising a quarter of the mileage in the Kingdom.

- The historian Raphael Samuel saw the late twentieth-century local authority turn to heritage promotion as a way of creating service jobs, protecting the environment and resisting urban decline as in some ways a revival of the Civic Gospel.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Briggs 1963, p. 195

- ^ Briggs 1963, p. 196

- ^ Briggs 1963, p. 197

- ^ Parsons 1988, p. 48

- ^ Parsons 1988, p. 47

- ^ Parsons 1988, p. 47

- ^ Parsons 1988, pp. 47–48

- ^ Parsons 1988, p. 48

- ^ Parsons 1988, p. 47

- ^ Wilson, Wright (1905). The Life of George Dawson, M.A. Glasgow (2nd ed.). Birmingham: Percival Jones. p. 152.

- ^ Hennock, E. P. (1973). Fit and Proper Persons: ideal and reality in nineteenth-century urban government. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 93–94. ISBN 9780713156652.

- ^ Parsons 1988, pp. 46–47

- ^ Hartnell, Roy (1996). Pre-Raphaelite Birmingham. Studley: Brewin Books. pp. 52–53. ISBN 1-85858-079-X.

- ^ Hartnell 1995, p. 229, citing Ralph, Julian (June 1890). "The best-governed city in the world". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. pp. 99–110.

- ^ Robson, Brian T. (2012) [1973]. Urban Growth: an approach. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 9781135676117.

- ^ Curran, James (2012). Media and Power. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781134900374.

- ^ Tanner, Duncan, ed. (2006). Debating Nationhood and Governance in Britain, 1885–1939: perspectives from the "four nations". Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 211. ISBN 9780719071669.

- ^ Samuel, Raphael (1998). Island Stories: Unravelling Britain: Theatres of Memory volume II. London: Verso. p. 296. ISBN 1859849652.

- ^ Webb, Sidney (1890). Socialism in England. London: Swan Sonnenschein. p. 102.

- ^ Samuel, Raphael (1994). Theatres of Memory: Volume 1: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture. London. p. 292. ISBN 0-86091-209-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Bartley, Paula (2000). "Moral regeneration: women and the civic gospel in Birmingham, 1870–1914". Midland History. 25: 143–61. doi:10.1179/mdh.2000.25.1.143. S2CID 143409331.

- Briggs, Asa (1963). "Birmingham: the making of a civic gospel". Victorian Cities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 184–240. ISBN 0-520-07922-1.

- Fraser, W. H. (1990). "From civic gospel to municipal socialism". In Fraser, Derek (ed.). Cities, Class and Communication: essays in honour of Asa Briggs. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. pp. 58–80. ISBN 0745006531.

- Green, Andy (2011). "'The anarchy of empire': reimagining Birmingham's civic gospel". Midland History. 36 (2): 163–179. doi:10.1179/004772911X13074595848951. S2CID 144782317.

- Hartnell, Roy (1995). "Art and civic culture in Birmingham in the late nineteenth century". Urban History. 22 (2): 229–237. doi:10.1017/S0963926800000493. S2CID 145701055.

- Parsons, Gerald (1988). "Social control to social gospel: Victorian Christian social attitudes". Religion in Victorian Britain: controversies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 39–62. ISBN 0719025133.

- Skipp, Victor (1983). "George Dawson and the Civic Gospel". The Making of Victorian Birmingham. Yardley. pp. 153–8. ISBN 0-9506998-3-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thompson, David Michael (1996). "R. W. Dale and the 'civic gospel'". In Sell, Alan P. F. (ed.). Protestant Nonconformists and the West Midlands of England. Keele: Keele University Press. pp. 99–118. ISBN 1853311731.

- Vail, Andy (2016). "Birmingham's protestant nonconformity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the theological context for the 'Civic Gospel'". In Cawood, Ian; Upton, Chris (eds.). Joseph Chamberlain: international statesman, national leader, local icon. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 211–28. ISBN 9781137528841.

- Wildman, Stephen (1997). "Pre-Raphaelism and the civic gospel: Burne-Jones and Ruskin in Birmingham". In Watson, Margaretta Frederick (ed.). Collecting the Pre-Raphaelites: the Anglo-American enchantment. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 15–24. ISBN 1859283993.