Madrid

Madrid | |

|---|---|

Location of Madrid | |

| Coordinates: 40°25′01″N 03°42′12″W / 40.41694°N 3.70333°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Community of Madrid |

| Founded | 9th century |

| Government | |

| • Type | Ayuntamiento |

| • Body | City Council of Madrid |

| • Mayor | José Luis Martínez-Almeida (PP) |

| Area | |

• Capital city and municipality | 604.31 km2 (233.33 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 650 m (2,130 ft) |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

• Capital city and municipality | 3,223,334 |

| • Rank | 2nd in the European Union 1st in Spain |

| • Density | 5,300/km2 (14,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 6,211,000[2] |

| • Metro | 6,791,667[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Madrilenian, Madrilene madrileño, -ña; matritense, gato, -a |

| GDP | |

| • Capital city and municipality | €135.6 billion (2020)[5] |

| • Metro | €261.7 billion (2022)[6] |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 28001–28080 |

| Area code | +34 (ES) + 91 (M) |

| HDI (2021) | 0.940[7] very high · 1st |

| Website | https://madrid.es |

Madrid (/məˈdrɪd/ mə-DRID; Spanish: [maˈðɾið] )[n. 1] is the capital and most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.4 million[10] inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and its monocentric metropolitan area is the second-largest in the EU.[2][11][12] The municipality covers 604.3 km2 (233.3 sq mi) geographical area.[13] Madrid lies on the River Manzanares in the central part of the Iberian Peninsula at about 650 meters above mean sea level. The capital city of both Spain and the surrounding autonomous community of Madrid (since 1983),[14]: 44 it is also the political, economic, and cultural centre of the country.[15] The climate of Madrid features hot summers and cool winters. The primitive core of Madrid, a walled military outpost, dates back to the late 9th century, under the Emirate of Córdoba. Conquered by Christians in 1083 or 1085, it consolidated in the Late Middle Ages as a sizeable town of the Crown of Castile. The development of Madrid as administrative centre fostered after 1561, as it became the permanent seat of the court of the Hispanic Monarchy.

The Madrid urban agglomeration has the fourth-largest GDP in the European Union and its influence in politics, education, entertainment, environment, media, fashion, science, culture, and the arts all contribute to its status as one of the world's major global cities.[16][17] Madrid is considered the major financial centre[18] and the leading economic hub of the Iberian Peninsula and of Southern Europe.[19][17] The metropolitan area hosts major Spanish companies such as Telefónica, Iberia, BBVA and FCC.[14]: 45 It concentrates the bulk of banking operations in the country and it is the Spanish-speaking city generating the largest number of webpages.[14]: 45

Madrid houses the headquarters of the UN's World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB), the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), and the Public Interest Oversight Board (PIOB). It also hosts major international regulators and promoters of the Spanish language: the Standing Committee of the Association of Spanish Language Academies, headquarters of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), the Instituto Cervantes and the Foundation of Urgent Spanish (FundéuRAE). Madrid organises fairs such as FITUR,[20] ARCO,[21] SIMO TCI[22] and the Madrid Fashion Week.[23] Madrid is home to two world-famous football clubs, Real Madrid and Atlético Madrid.

While Madrid possesses modern infrastructure, it has preserved the look and feel of many of its historic neighbourhoods and streets. Its landmarks include the Plaza Mayor, the Royal Palace of Madrid; the Royal Theatre with its restored 1850 Opera House; the Buen Retiro Park, founded in 1631; the 19th-century National Library building (founded in 1712) containing some of Spain's historical archives; many national museums,[24] and the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three art museums: Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Museum, a museum of modern art, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which complements the holdings of the other two museums.[25] The mayor is José Luis Martínez-Almeida from the People's Party.[26]

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the name is unknown. There are various theories regarding the origin of the toponym "Madrid" (all of them with problems when it comes to fully explaining the phonetic evolution of the toponym), namely:[27]

- A Celtic origin (Madrid < *Magetoritum;[27]: 701 with the root "-ritu" meaning "ford").

- From the Arabic maǧrà / majrā (meaning "water stream")[27]: 701 or Arabic: مجريػ, romanized: mayrit, lit. '"spring", "fountain"'.[28]

- A Mozarabic variant of the Latin matrix, matricis (also meaning "water stream").[27]: 701

Nicknames for Madrid include the plural Los Madriles[29] and La Villa y Corte (lit. 'the town and court').

History

[edit]The site of modern-day Madrid has been occupied since prehistoric times,[30][31][32] and there are archaeological remains of the Celtic Carpetani settlement, Roman villas,[33] a Visigoth basilica near the church of Santa María de la Almudena[34] and three Visigoth necropolises near Casa de Campo, Tetuán and Vicálvaro.[35]

Middle Ages

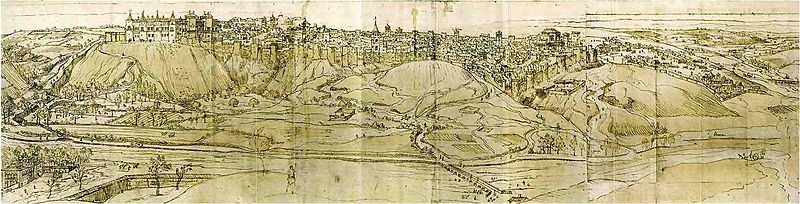

[edit]The first historical document about the existence of an established settlement in Madrid dates from the Muslim age. In the second half of the 9th century,[36] Umayyad Emir Muhammad I built a fortress on a headland near the river Manzanares[37] as one of the many fortresses he ordered to be built on the border between Al-Andalus and the kingdoms of León and Castile, with the objective of protecting Toledo from the Christian reconquests and also as a starting point for Muslim offensives. After the disintegration of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the early 11th century, Madrid was integrated in the Taifa of Toledo.

In the context of the wider campaign for the conquest of the taifa of Toledo initiated in 1079, Madrid was seized in 1083 by Alfonso VI of León and Castile, who sought to use the town as an offensive outpost against the city of Toledo,[38] in turn conquered in 1085. Following the conquest, Christians occupied the center of the city, while Muslims and Jews were displaced to the suburbs. Madrid, located near Alcalá (under Muslim control until 1118), remained a borderland for a while, suffering a number of razzias during the Almoravid period, and its walls were destroyed in 1110.[38] The city was confirmed as villa de realengo (linked to the Crown) in 1123, during the reign of Alfonso VII.[39] The 1123 Charter of Otorgamiento established the first explicit limits between Madrid and Segovia, namely the Puerto de El Berrueco and the Puerto de Lozoya.[40] Beginning in 1188, Madrid had the right to be a city with representation in the courts of Castile.[citation needed] In 1202, Alfonso VIII gave Madrid its first charter to regulate the municipal council,[41] which was expanded in 1222 by Ferdinand III. The government system of the town was changed to a regimiento of 12 regidores by Alfonso XI on 6 January 1346.[42]

Starting in the mid-13th century and up to the late 14th century, the concejo of Madrid vied for the control of the Real de Manzanares territory against the concejo of Segovia, a powerful town north of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range, characterised by its repopulating prowess and its husbandry-based economy, contrasted with the agricultural and less repopulated town of Madrid.[43] After the decline of Sepúlveda, another concejo north of the mountain range, Segovia had become a major actor south of the Guadarrama mountains, expanding across the Lozoya and Manzanares rivers to the north of Madrid and along the Guadarrama river course to its west.[43]

In 1309, the Courts of Castile convened at Madrid for the first time under Ferdinand IV, and later in 1329, 1339, 1391, 1393, 1419 and twice in 1435.

Modern Age

[edit]During the revolt of the Comuneros, led by Juan Lopez de Padilla, Madrid joined the revolt against Charles, Holy Roman Emperor, but after defeat at the Battle of Villalar, Madrid was besieged and occupied by the imperial troops. The city was however granted the titles of Coronada (Crowned) and Imperial.

The number of urban inhabitants grew from 4,060 in the year 1530 to 37,500 in the year 1594. The poor population of the court was composed of ex-soldiers, foreigners, rogues and Ruanes, dissatisfied with the lack of food and high prices. In June 1561 Phillip II set his court in Madrid, installing it in the old alcázar.[44] Thanks to this, the city of Madrid became the political centre of the monarchy, being the capital of Spain except for a short period between 1601 and 1606, in which the Court was relocated to Valladolid (and the Madrid population temporarily plummeted accordingly). Being the capital was decisive for the evolution of the city and influenced its fate and during the rest of the reign of Philip II, the population boomed, going up from about 18,000 in 1561 to 80,000 in 1598.[45]

During the early 17th century, although Madrid recovered from the loss of the capital status, with the return of diplomats, lords and affluent people, as well as an entourage of noted writers and artists together with them, extreme poverty was however rampant.[46] The century also was a time of heyday for theatre, represented in the so-called corrales de comedias.[47]

The city changed hands several times during the War of the Spanish Succession: from the Bourbon control it passed to the allied "Austracist" army with Portuguese and English presence that entered the city in late June 1706,[48] only to be retaken by the Bourbon army on 4 August 1706.[49] The Habsburg army led by the Archduke Charles entered the city for a second time in September 1710,[50] leaving the city less than three months after. Philip V entered the capital on 3 December 1710.[51]

Seeking to take advantage of the Madrid's location at the geographic centre of Spain, the 18th century saw a sustained effort to create a radial system of communications and transports for the country through public investments.[52]

Philip V built the Royal Palace, the Royal Tapestry Factory and the main Royal Academies.[53] The reign of Charles III, who came to be known as "the best mayor of Madrid", saw an effort to turn the city into a true capital, with the construction of sewers, street lighting, cemeteries outside the city and a number of monuments and cultural institutions. The reforms enacted by his Sicilian minister were however opposed in 1766 by the populace in the so-called Esquilache Riots, a revolt demanding to repeal a clothing decree banning the use of traditional hats and long cloaks aiming to curb crime in the city.[54]

In the context of the Peninsular War, the situation in French-occupied Madrid after March 1808 was becoming more and more tense. On 2 May, a crowd began to gather near the Royal Palace protesting against the French attempt to evict the remaining members of the Bourbon royal family to Bayonne, prompting up an uprising against the French Imperial troops that lasted hours and spread throughout the city, including a famous last stand at the Monteleón barracks. Subsequent repression was brutal, with many insurgent Spaniards being summarily executed.[55] The uprising led to a declaration of war calling all the Spaniards to fight against the French invaders.

Capital of the Liberal State

[edit]

The city was invaded on 24 May 1823 by a French army—the so-called Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis—called to intervene to restore the absolutism of Ferdinand that the latter had been deprived from during the 1820–1823 trienio liberal.[56] Unlike other European capitals, during the first half of the 19th century the only noticeable bourgeois elements in Madrid (that experienced a delay in its industrial development up to that point) were merchants.[57] The University of Alcalá de Henares was relocated to Madrid in 1836, becoming the Central University.[58]

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors.[59] The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.[60] Electric lighting in the streets was introduced in the 1890s.[60]

During the first third of the 20th century the population nearly doubled, reaching more than 850,000 inhabitants. New suburbs such as Las Ventas, Tetuán and El Carmen became the homes of the influx of workers, while Ensanche became a middle-class neighbourhood of Madrid.[61]

Second Republic and Civil War

[edit]

The Spanish Constitution of 1931 was the first to legislate the location of the country's capital, setting it explicitly in Madrid. During the 1930s, Madrid enjoyed "great vitality"; it was demographically young, becoming urbanized and the centre of new political movements.[62] During this time, major construction projects were undertaken, including the northern extension of the Paseo de la Castellana, one of Madrid's major thoroughfares.[63] The tertiary sector, including banking, insurance and telephone services, grew greatly.[64] Illiteracy rates were down to below 20%, and the city's cultural life grew notably during the so-called Silver Age of Spanish Culture; the sales of newspapers also increased.[65] Conversely, the proclamation of the Republic created a severe housing shortage. Slums and squalor grew due to high population growth and the influx of the poor to the city. Construction of affordable housing failed to keep pace and increased political instability discouraged economic investment in housing in the years immediately prior to the Civil War.[66] Anti-clericalism and Catholicism lived side by side in Madrid; the burning of convents initiated after riots in the city in May 1931 worsened the political environment.[67] However, the 1934 insurrection largely failed in the city.[68]

Madrid was one of the most heavily affected cities in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). It was a stronghold of the Republican faction from July 1936 and became an international symbol of anti-fascist struggle during the conflict.[69] The city suffered aerial bombing, and in November 1936, its western suburbs were the scene of an all-out battle.[70] The city fell to the Francoists in March 1939.

Francoist dictatorship

[edit]

A staple of post-war Madrid (Madrid de la posguerra) was the widespread use of ration coupons.[71] Meat and fish consumption was scarce, resulting in high mortality due to malnutrition.[72] Due to Madrid's history as a left-wing stronghold, the right-wing victors considered moving the capital elsewhere (most notably to Seville), but such plans were never implemented. The Franco regime instead emphasized the city's history as the capital of formerly imperial Spain.[73]

The intense demographic growth experienced by the city via mass immigration from the rural areas of the country led to the construction of abundant housing in the peripheral areas of the city to absorb the new population (reinforcing the processes of social polarization of the city),[74] initially comprising substandard housing (with as many as 50,000 shacks scattered around the city by 1956).[75] A transitional planning intended to temporarily replace the shanty towns were the poblados de absorción, introduced since the mid-1950s in locations such as Canillas, San Fermín, Caño Roto, Villaverde, Pan Bendito, Zofío and Fuencarral, aiming to work as a sort of "high-end" shacks (with the destinataries participating in the construction of their own housing) but under the aegis of a wider coordinated urban planning.[76]

Madrid grew through the annexation of neighboring municipalities, achieving the present extent of 607 km2 (234.36 sq mi). The south of Madrid became heavily industrialized, and there was significant immigration from rural areas of Spain. Madrid's newly built north-western districts became the home of a newly enriched middle class that appeared as result of the 1960s Spanish economic boom, while the south-eastern periphery became a large working-class area, which formed the base for active cultural and political movements.[70]

Recent history

[edit]After the fall of the Francoist regime, the new 1978 constitution confirmed Madrid as the capital of Spain. The 1979 municipal election brought Madrid's first democratically elected mayor since the Second Republic to power.

Madrid was the scene of some of the most important events of the time, such as the mass demonstrations of support for democracy after the failed coup, 23-F, on 23 February 1981. The first democratic mayors belonged to the centre-left PSOE (Enrique Tierno Galván, Juan Barranco Gallardo). Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as la Movida. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.[77]

Benefiting from increasing prosperity in the 1980s and 1990s, the capital city of Spain consolidated its position as an important economic, cultural, industrial, educational, and technological centre on the European continent.[70] During the mandate as Mayor of José María Álvarez del Manzano construction of traffic tunnels below the city proliferated.[78] The following administrations, also conservative, led by Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón and Ana Botella launched three unsuccessful bids for the 2012, 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics.[79] By 2005, Madrid was the leading European destination for migrants from developing countries, as well as the largest employer of non-European workforce in Spain.[80] Madrid was a centre of the anti-austerity protests that erupted in Spain in 2011.[81] As consequence of the spillover of the 2008 financial and mortgage crisis, Madrid has been affected by the increasing number of second-hand homes held by banks and house evictions.[82] The mandate of left-wing Mayor Manuela Carmena (2015–2019) delivered the renaturalization of the course of the Manzanares across the city.

Since the late 2010s, the challenges the city faces include the increasingly unaffordable rental prices (often in parallel with the gentrification and the spike of tourist apartments in the city centre) and the profusion of betting shops in working-class areas, leading to an "epidemic" of gambling among young people.[83][84]

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]

Madrid lies in the centre of the Iberian peninsula on the southern Meseta Central, 60 km south of the Guadarrama mountain range and straddling the Jarama and Manzanares river sub-drainage basins, in the wider Tagus River catchment area. With an average altitude of 650 m (2,130 ft), Madrid is the second highest capital of Europe (after Andorra la Vella).[85] The difference in altitude within the city proper ranges from the 700 m (2,297 ft) around Plaza de Castilla in the north of city to the 570 m (1,870 ft) around La China wastewater treatment plant on the Manzanares' riverbanks, near the latter's confluence with the Fuente Castellana thalweg in the south of the city.[86] The Monte de El Pardo (a protected forested area covering over a quarter of the municipality) reaches its top altitude (843 m (2,766 ft)) on its perimeter, in the slopes surrounding El Pardo reservoir located at the north-western end of the municipality, in the Fuencarral-El Pardo district.[87]

The oldest urban core is located on the hills next to the left bank of the Manzanares River.[88] The city grew to the east, reaching the Fuente Castellana Creek (now the Paseo de la Castellana), and further east reaching the Abroñigal Creek (now the M-30).[88] The city also grew through the annexation of neighbouring urban settlements,[88] including those to the South West on the right bank of the Manzanares.

Parks and forests

[edit]Madrid has the second highest number of aligned trees in the world, with 248,000 units, only exceeded by Tokyo. Madrid's citizens have access to a green area within a 15-minute walk. Since 1997, green areas have increased by 16%. At present, 8.2% of Madrid's grounds are green areas, meaning that there are 16 m2 (172 sq ft) of green area per inhabitant, far exceeding the 10 m2 (108 sq ft) per inhabitant recommended by the World Health Organization.

A great bulk of the most important parks in Madrid are related to areas originally belonging to the royal assets (including El Pardo, Soto de Viñuelas, Casa de Campo, El Buen Retiro, la Florida and the Príncipe Pío hill, and the Queen's Casino).[89] The other main source for the "green" areas are the bienes de propios owned by the municipality (including the Dehesa de la Villa, the Dehesa de Arganzuela or Viveros).[90]

El Retiro is the most visited location of the city.[91] Having an area bigger than 1.4 km2 (0.5 sq mi) (350 acres), it is the largest park within the Almendra Central, the inner part of the city enclosed by the M-30. Created during the reign of Philip IV (17th century), it was handed over to the municipality in 1868, after the Glorious Revolution.[92][93] It lies next to the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid.

Located northwest of the city centre, the Parque del Oeste ("Park of the West") comprises part of the area of the former royal possession of the "Real Florida", and it features a slope as the height decreases down to the Manzanares.[94] Its southern extension includes the Temple of Debod, a transported ancient Egyptian temple.[95]

Other urban parks are the Parque de El Capricho, the Parque Juan Carlos I (both in northeast Madrid), Madrid Río, the Enrique Tierno Galván Park, the San Isidro Park as well as gardens such as the Campo del Moro (opened to the public in 1978)[90] and the Sabatini Gardens (opened to the public in 1931)[90] adjacent to the Royal Palace.

Further west, across the Manzanares, lies the Casa de Campo, a large forested area with more than 1700 hectares (6.6 sq mi) where the Madrid Zoo, and the Parque de Atracciones de Madrid amusement park are located. It was ceded to the municipality following the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931.[96]

The Monte de El Pardo is the largest forested area in the municipality. A holm oak forest covering a surface over 16,000 hectares, it is considered the best preserved mediterranean forest in the Community of Madrid and one of the best preserved in Europe.[97] Already mentioned in the Alfonso XI's Libro de la montería from the mid-14th century, its condition as hunting location linked to the Spanish monarchy help to preserve the environmental value.[97] During the reign of Ferdinand VII the regime of hunting prohibition for the Monte de El Pardo became one of full property and the expropriation of all possessions within its bounds was enforced, with dire consequences for the madrilenians at the time.[98] It is designated as Special Protection Area for bird-life and it is also part of the Regional Park of the High Basin of the Manzanares.

Other large forested areas include the Soto de Viñuelas, the Dehesa de Valdelatas and the Dehesa de la Villa. As of 2015, the most recent big park in the municipality is the Valdebebas Park. Covering a total area of 4.7 km2 (1.8 sq mi), it is sub-divided in a 3.4 km2 (1.3 sq mi) forest park (the Parque forestal de Valdebebas-Felipe VI), a 0.8 km2 (0.31 sq mi) periurban park as well as municipal garden centres and compost plants.[99]

Climate

[edit]

Madrid has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk), transitioning to a Mediterranean climate (Csa) in the western half.[100] The city has continental influences.

Winters are cool due to its altitude, which is approximately 667 m (2,188 ft) above sea level and distance from the moderating effect of the sea. While mostly sunny, rain, sporadic snowfalls and frequent frosts can occur between December and February with cooler temperatures particularly during the night and mornings as cold winds blow into the city from surrounding mountains. Summers are hot and sunny, in the warmest month, July, average temperatures during the day range from 32 to 34 °C (90 to 93 °F) depending on location, with maxima commonly climbing over 35 °C (95 °F) and occasionally up to 40 °C during the frequent heat waves. Due to Madrid's altitude and dry climate, humidity is low and diurnal ranges are often significant, particularly on sunny winter days when the temperature rises in the afternoon before rapidly plummeting after nightfall. Madrid is among the sunniest capital cities in Europe.

The highest recorded temperature was on 14 August 2021, with 40.7 °C (105.3 °F) and the lowest recorded temperature was on 16 January 1945 with −10.1 °C (13.8 °F) in Madrid.[101] While at the airport, in the eastern side of the city, the highest recorded temperature was on 24 July 1995, at 42.2 °C (108.0 °F), and the lowest recorded temperature was on 16 January 1945 at −15.3 °C (4.5 °F).[102] From 7 to 9 January 2021, Madrid received the most snow in its recorded history since 1904; Spain's meteorological agency AEMET reported between 50 and 60 cm (20 and 24 in) of accumulated snow in its weather stations within the city.[103]

Precipitation is typically concentrated in the autumn, winter, and spring. It is particularly sparse during the summer, taking the form of about two showers and/or thunderstorms during the season. Madrid is the european capital with the least amount of annual precipitation.[104][105]

At the metropolitan scale, Madrid features both substantial daytime urban cool island and nighttime urban heat island effects during the summer season in relation to its surroundings, which feature thinly vegetated dry land.[106]

| Climate data for Madrid (667 m), Buen Retiro Park in the city centre (1991–2020) Sunshine (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.5 (95.9) |

40.7 (105.3) |

40.7 (105.3) |

40.7 (105.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

30.1 (86.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

20.3 (68.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

15.4 (59.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

10.4 (50.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 32.0 (1.26) |

34.0 (1.34) |

35.0 (1.38) |

46.0 (1.81) |

48.0 (1.89) |

20.0 (0.79) |

9.0 (0.35) |

10.0 (0.39) |

24.0 (0.94) |

64.0 (2.52) |

52.0 (2.05) |

42.0 (1.65) |

416 (16.37) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 5.5 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 59.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (daily average) | 72.0 | 64.0 | 57.0 | 56.0 | 54.0 | 45.0 | 39.0 | 42.0 | 51.0 | 66.0 | 72.0 | 75.0 | 57.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149 | 158 | 211 | 230 | 268 | 315 | 355 | 332 | 259 | 199 | 144 | 124 | 2,744 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[107][108] | |||||||||||||

Water supply

[edit]

In the 17th century, the viajes de agua (a kind of water channel or qanat) were used to provide water to the city. Some of the most important ones were the Viaje de Amaniel (1610–1621, sponsored by the Crown), the Viaje de Fuente Castellana (1613–1620) and Abroñigal Alto/Abroñigal Bajo (1617–1630), sponsored by the City Council. They were the main infrastructure for the supply of water until the arrival of the Canal de Isabel II in the mid-19th century.[109]

Madrid derives almost 73.5 percent of its water supply from dams and reservoirs built on the Lozoya River, such as the El Atazar Dam.[110] This water supply is managed by the Canal de Isabel II, a public entity created in 1851. It is responsible for the supply, depurating waste water and the conservation of all the natural water resources of the Madrid region.

Demographics

[edit]

The population of Madrid has overall increased since the city became the capital of Spain in the mid-sixteenth century, and has stabilised at approximately 3,000,000 since the 1970s.

From 1970 until the mid-1990s, the population dropped. This phenomenon, which also affected other European cities, was caused in part by the growth of satellite suburbs at the expense of the downtown region within the city proper.

The demographic boom accelerated in the late-1990s and early first decade of the 21st century due to immigration in parallel with a surge in Spanish economic growth.

The wider Madrid region is the EU region with the highest average life expectancy at birth. The average life expectancy was 82.2 years for males and 87.8 for females in 2016.[111]

As the capital city of Spain, the city has attracted many immigrants from around the world, with most of the immigrants coming from Latin American countries.[112] In 2020, around 76% of the registered population was Spain-born,[113] while, regarding the foreign-born population (24%),[113] the bulk of it relates to the Americas (around 16% of the total population), and a lesser fraction of the population is born in other European, Asian and African countries.

As of 2019, the fastest-growing group of immigrants were Venezuelans, who consisted of a population of 60,000 in Madrid alone. This made them the second-largest community of foreign origin at the time after Ecuadorians, with a population of 88,000.[114]

Regarding religious beliefs, according to a 2019 Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) survey with a sample size of 469 respondents, 20.7% of respondents in Madrid identify themselves as practising Catholics, 45.8% as non-practising Catholics, 3.8% as believers of another religion, 11.1% as agnostics, 3.6% as indifferent towards religion, and 12.8% as atheists. The remaining 2.1% did not state their religious beliefs.[115]

The Madrid metropolitan area comprises Madrid and the surrounding municipalities. According to Eurostat, the "metropolitan region" of Madrid has a population of slightly more than 6.271 million people[116] covering an area of 4,609.7 km2 (1,780 sq mi). It is the largest in Spain and the second largest in the European Union.[2][11][12]

Government

[edit]Local government and administration

[edit]The City Council (Ayuntamiento de Madrid) is the body responsible for the government and administration of the municipality. It is formed by the Plenary (Pleno), the Mayor (alcalde) and the Government Board (Junta de Gobierno de la Ciudad de Madrid).

The Plenary of the Ayuntamiento is the body of political representation of the citizens in the municipal government. Its 57 members are elected for a 4-year mandate. Some of its attributions are: fiscal matters, the election and deposition of the mayor, the approval and modification of decrees and regulations, the approval of budgets, the agreements related to the limits and alteration of the municipal term, the services management, the participation in supramunicipal organisations, etc.[117]

The mayor, the supreme representative of the city, presides over the Ayuntamiento. He is charged with giving impetus to the municipal policies, managing the action of the rest of bodies and directing the executive municipal administration.[118] He is responsible to the Pleno. He is also entitled to preside over the meetings of the Pleno, although this responsibility can be delegated to another municipal councillor. José Luis Martínez-Almeida, a member of the People's Party, has served as mayor since 2019.

The Government Board consists of the mayor, deputy mayors and a number of delegates assuming the portfolios for the different government areas. All those positions are held by municipal councillors.[119]

Since 2007, the Cybele Palace (or Palace of Communications) serves as City Hall.

Capital of Spain

[edit]

Madrid is the capital of Spain. The King of Spain, the country's head of state, has his official residence in the Zarzuela Palace. As the seat of the Government of Spain, Madrid also houses the official residence of the President of the Government (Prime Minister) and regular meeting place of the Council of Ministers, the Moncloa Palace, as well as the headquarters of the ministerial departments. Both the residences of the head of state and government are located at the northwest of the city. Additionally, the seats of the Lower and Upper Chambers of the Spanish Parliament, the Cortes Generales (respectively, the Palacio de las Cortes and the Palacio del Senado), also lie in Madrid.

Regional capital

[edit]Madrid is the capital of the Community of Madrid. The region has its own legislature and enjoys a wide range of competencies in areas such as social spending, healthcare, and education. The seat of the regional parliament, the Assembly of Madrid, is located at the district of Puente de Vallecas. The presidency of the regional government is headquartered at the Royal House of the Post Office at the very centre of the city, the Puerta del Sol.

Law enforcement

[edit]

The Madrid Municipal Police (Policía Municipal de Madrid) is the local law enforcement body, dependent on the Ayuntamiento. As of 2018, it had a workforce of 6,190 civil servants.[120]

The headquarters of both the Directorate-General of the Police and the Directorate-General of the Civil Guard are located in Madrid. The headquarters of the Higher Office of Police of Madrid (Jefatura Superior de Policía de Madrid), the peripheral branch of the National Police Corps with jurisdiction over the region also lies in Madrid.

Administrative subdivisions

[edit]Madrid is administratively divided into 21 districts, which are further subdivided into 131 neighbourhoods (barrios):

| District | Population (1 Jan 2023)[121] | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Centro | 138,204 | 522.82 |

| Arganzuela | 153,304 | 646.22 |

| Retiro | 117,918 | 546.62 |

| Salamanca | 145,702 | 539.24 |

| Chamartín | 144,796 | 917.55 |

| Tetuán | 160,002 | 537.47 |

| Chamberí | 138,204 | 467.92 |

| Fuencarral-El Pardo | 248,443 | 23,783.84 |

| Moncloa-Aravaca | 121,757 | 4,653.11 |

| Latina | 241,672 | 2,542.72 |

| Carabanchel | 262,339 | 1,404.83 |

| Usera | 142,746 | 777.77 |

| Puente de Vallecas | 241,603 | 1,496.86 |

| Moratalaz | 92,814 | 610.32 |

| Ciudad Lineal | 220,345 | 1,142.57 |

| Hortaleza | 198,391 | 2,741.98 |

| Villaverde | 159,038 | 2,018.76 |

| Villa de Vallecas | 117,501 | 5,146.72 |

| Vicálvaro | 83,804 | 3,526.67 |

| San Blas-Canillejas | 161,219 | 2,229.24 |

| Barajas | 48,646 | 4,192.28 |

| Total | 3,339,931 | 60,445.51 |

Economy

[edit]

After it became the capital of Spain in the 16th century, Madrid was more a centre of consumption than of production or trade. Economic activity was largely devoted to supplying the city's own rapidly growing population, including the royal household and national government, and to such trades as banking and publishing.

A large industrial sector did not develop until the 20th century, but thereafter industry greatly expanded and diversified, making Madrid the second industrial city in Spain. However, the economy of the city is now becoming more and more dominated by the service sector. A major European financial center, its stock market is the third largest stock market in Europe featuring both the IBEX 35 index and the attached Latibex stock market (with the second most important index for Latin American companies).[14]: 45

Madrid is the 5th most important leading Centre of Commerce in Europe (after London, Paris, Frankfurt and Amsterdam) and ranks 11th in the world.[19] It is the leading Spanish-speaking city in terms of webpage creation.[14]: 45

Economic history

[edit]As the capital city of the Spanish Empire from 1561, Madrid's population grew rapidly. Administration, banking, and small-scale manufacturing centred on the royal court were among the main activities, but the city was more a locus of consumption than production or trade, geographically isolated as it was before the coming of the railways.

The Bank of Spain is one of the oldest European central banks. Originally named as the Bank of San Carlos as it was founded in 1782, it was later renamed to Bank of San Fernando in 1829 and ultimately became the Bank of Spain in 1856.[122] Its headquarters are located at the calle de Alcalá. The Madrid Stock Exchange was inaugurated on 20 October 1831.[123] Its benchmark stock market index is the IBEX 35.

Industry started to develop on a large scale only in the 20th century,[124] but then grew rapidly, especially during the "Spanish miracle" period around the 1960s. The economy of the city was then centred on manufacturing industries such as those related to motor vehicles, aircraft, chemicals, electronic devices, pharmaceuticals, processed food, printed materials, and leather goods.[125] Since the restoration of democracy in the late 1970s, the city has continued to expand. Its economy is now among the most dynamic and diverse in the European Union.[126]

Present-day economy

[edit]

Madrid concentrates activities directly connected with power (central and regional government, headquarters of Spanish companies, regional HQ of multinationals, financial institutions) and with knowledge and technological innovation (research centres and universities). It is one of Europe's largest financial centres, and the largest in Spain.[127] The city has 17 universities and over 30 research centres.[127]: 52 It is the second metropolis in the EU by population, and the third by gross internal product.[127]: 69 Leading employers include Telefónica, Iberia, Prosegur, BBVA, Urbaser, Dragados, and FCC.[127]: 569

The Community of Madrid, the region comprising the city and the rest of municipalities of the province, had a GDP of €220B in 2017, equating to a GDP per capita of €33,800.[128] In 2011 the city itself had a GDP per capita 74% above the national average and 70% above that of the 27 European Union member states, although 11% behind the average of the top 10 cities of the EU.[127]: 237–239 Although housing just over 50% of the region's's population, the city generates 65.9% of its GDP.[127]: 51 Following the recession commencing 2007/8, recovery was under way by 2014, with forecast growth rates for the city of 1.4% in 2014, 2.7% in 2015 and 2.8% in 2016.[129]: 10

The economy of Madrid has become based increasingly on the service sector. In 2011 services accounted for 85.9% of value added, while industry contributed 7.9% and construction 6.1%.[127]: 51 Nevertheless, Madrid continues to hold the position of Spain's second industrial centre after Barcelona, specialising particularly in high-technology production. Following the recession, services and industry were forecast to return to growth in 2014, and construction in 2015.[129]: 32 [needs update]

Standard of living

[edit]Mean household income and spending are 12% above the Spanish average.[127]: 537, 553 The proportion classified as "at risk of poverty" in 2010 was 15.6%, up from 13.0% in 2006 but less than the average for Spain of 21.8%. The proportion classified as affluent was 43.3%, much higher than Spain overall (28.6%).[127]: 540–3

Consumption by Madrid residents has been affected by job losses and by austerity measures, including a rise in sales tax from 8% to 21% in 2012.[130]

Although residential property prices have fallen by 39% since 2007, the average price of dwelling space was €2,375.6 per sq. m. in early 2014,[129]: 70 and is shown as second only to London in a list of 22 European cities.[131]

Employment

[edit]Participation in the labour force was 1,638,200 in 2011, or 79.0%. The employed workforce comprised 49% women in 2011 (Spain, 45%).[127]: 98 41% of economically active people are university graduates, against 24% for Spain as a whole.[127]: 103

In 2011, the unemployment rate was 15.8%, remaining lower than in Spain as a whole. Among those aged 16–24, the unemployment rate was 39.6%.[127]: 97, 100 Unemployment reached a peak of 19.1% in 2013,[129]: 17 but with the start of an economic recovery in 2014, employment started to increase.[132] Employment continues to shift further towards the service sector, with 86% of all jobs in this sector by 2011, against 74% in all of Spain.[127]: 117 In the second quarter of 2018 the unemployment rate was 10.06%.[133]

Services

[edit]

The share of services in the city's economy is 86%. Services for business, transport & communications, property, and financial together account for 52% of the total value added.[127]: 51 The types of services that are now expanding are mainly those that facilitate movement of capital, information, goods and persons, and "advanced business services" such as research and development (R&D), information technology, and technical accountancy.[127]: 242–3

Madrid and the wider region's authorities have put a notable effort in the development of logistics infrastructure. Within the city proper, some of the standout centres include Mercamadrid, the Madrid-Abroñigal logistics centre, the Villaverde's Logistics Centre and the Vicálvaro's Logistics Centre to name a few.[134]

Banks based in Madrid carry out 72% of the banking activity in Spain.[127]: 474 The Spanish central bank, Bank of Spain, has existed in Madrid since 1782. Stocks & shares, bond markets, insurance, and pension funds are other important forms of financial institution in the city.

Madrid is an important centre for trade fairs, many of them coordinated by IFEMA, the Trade Fair Institution of Madrid.[127]: 351–2 The public sector employs 18.1% of all employees.[127]: 630 Madrid attracts about 8M tourists annually from other parts of Spain and from all over the world, exceeding even Barcelona.[127]: 81 [127]: 362, 374 [129]: 44 Spending by tourists in Madrid was estimated (2011) at €9,546.5M, or 7.7% of the city's GDP.[127]: 375

The construction of transport infrastructure has been vital to maintain the economic position of Madrid. Travel to work and other local journeys use a high-capacity metropolitan road network and a well-used public transport system.[127]: 62–4 In terms of longer-distance transport, Madrid is the central node of the system of autovías and of the high-speed rail network (AVE), which has brought major cities such as Seville and Barcelona within 2.5 hours travel time.[127]: 72–75 Also important to the city's economy is Madrid-Barajas Airport, the fourth largest airport in Europe.[127]: 76–78 Madrid's central location makes it a major logistical base.[127]: 79–80

Industry

[edit]

As an industrial centre Madrid retains its advantages in infrastructure, as a transport hub, and as the location of headquarters of many companies. Industries based on advanced technology are acquiring much more importance here than in the rest of Spain.[127]: 271 Industry contributed 7.5% to Madrid's value-added in 2010.[127]: 265 However, industry has slowly declined within the city boundaries as more industry has moved outward to the periphery. Industrial Gross Value Added grew by 4.3% in the period 2003–2005, but decreased by 10% during 2008–2010.[127]: 271, 274 The leading industries were: paper, printing & publishing, 28.8%; energy & mining, 19.7%; vehicles & transport equipment, 12.9%; electrical and electronic, 10.3%; foodstuffs, 9.6%; clothing, footwear & textiles, 8.3%; chemical, 7.9%; industrial machinery, 7.3%.[127]: 266

The PSA Peugeot Citroën plant is located in Villaverde district.

Construction

[edit]

The construction sector, contributing 6.5% to the city's economy in 2010,[127]: 265 was a growing sector before the recession, aided by a large transport and infrastructure program. More recently the construction sector has fallen away and earned 8% less in 2009 than it had been in 2000.[127]: 242–3 The decrease was particularly marked in the residential sector, where prices dropped by 25%–27% from 2007 to 2012/13[127]: 202, 212 and the number of sales fell by 57%.[127]: 216

Tourism

[edit]

Madrid is the seat of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the International Tourism Fair (FITUR).

In 2018, the city received 10.21 million tourists (53.3% of them international tourists).[135]p. 9 The biggest share of international tourists come from the United States, followed by Italy, France, United Kingdom and Germany.[135]p. 10 As of 2018, the city has 793 hotels, 85,418 hotel places and 43,816 hotel rooms.[135]p. 18 It also had, as of 2018, an estimated 20,217 tourist apartments.[135]p. 20

The most visited museum was the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, with 3.8 million visitors in the sum of its three seats in 2018. Conversely, the Prado Museum had 2.8 million visitors and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum 906,815 visitors.[135]p. 32

By the late 2010s, the gentrification and the spike of tourist apartments in the city centre led to an increase in rental prices, pushing residents out of the city centre.[84] Most of the tourist apartments in Madrid (50–54%) are located in the Centro District.[136] In the Sol neighborhood (part of the latter district), 3 out of 10 homes are dedicated to tourist apartments,[136] and 2 out of 10 are listed in AirBnB.[84] In April 2019 the plenary of the ayuntamiento passed a plan intending to regulate this practice, seeking to greatly limit the number of tourist apartments. The normative would enforce a requirement for independent access to those apartments on and off the street.[137] However, after the change of government in June 2019, the new municipal administration planned to revert the regulation.[138]

International rankings

[edit]A recent study placed Madrid 7th among 36 cities as an attractive base for business.[139] It was placed third in terms of availability of office space, and fifth for ease of access to markets, availability of qualified staff, mobility within the city, and quality of life. Its less favourable characteristics were seen as pollution, languages spoken, and political environment. Another ranking of European cities placed Madrid 5th among 25 cities (behind Berlin, London, Paris and Frankfurt), being rated favourably on economic factors and the labour market as well as transport and communication.[140]

Media and entertainment

[edit]The Madrid metropolitan area is an important film and television production hub, whose content is distributed throughout the Spanish-speaking world and abroad. It is often seen as the entry point into the European media market for Latin American media companies, and likewise the entry point into the Latin American markets for European companies.[141] It is also the headquarters of media groups such as Radiotelevisión Española (RTVE), Atresmedia, Mediaset España, and Movistar+, which produce numerous films, television shows and series which are distributed globally on various platforms.[142] Since 2018, it is also home to Netflix's Madrid Production Hub, Mediapro Studio, and numerous others such as Viacom International Studios.[143][144][145][146] As of 2019, the film and television industry employs 19,000 people locally (44% of people in Spain working in this industry).[147]

The Torrespaña broadcasting tower, located in Madrid's Salamanca district, is the central and main transmission node of the terrestrial broadcasting network in Spain. RTVE, the state-owned radio and television public broadcaster is headquartered in Pozuelo de Alarcón along with all its channels and web services (La 1, La 2, Clan, Teledeporte, 24 Horas, TVE Internacional, Radio Nacional, Radio Exterior, and Radio Clásica). Atresmedia group (Antena 3, La Sexta, Onda Cero) is headquartered in San Sebastián de los Reyes. Mediaset España (Telecinco, Cuatro) maintains its headquarters in Madrid's Fuencarral-El Pardo district. Together with RTVE, Atresmedia and Mediaset account for nearly the 80% of share of generalist television.[148] The Spanish media conglomerate PRISA (Cadena SER, Los 40 Principales, M80 Radio, Cadena Dial) is headquartered in Gran Vía street in central Madrid.

Besides hosting the main television and radio producers and broadcasters, the metropolitan area hosts most of the major written mass media in Spain,[148] including ABC, El País, El Mundo, La Razón, Marca, ¡Hola!, Diario AS, El Confidencial and Cinco Días. The Spanish international news agency EFE maintains its headquarters in Madrid since its inception in 1939. The second news agency of Spain is the privately owned Europa Press, founded and headquartered in Madrid since 1953.

Culture

[edit]Architecture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

Little medieval architecture is preserved in Madrid, mostly in the Almendra Central, including the San Nicolás and San Pedro el Viejo church towers, the church of San Jerónimo el Real, and the Bishop's Chapel. Nor has Madrid retained much Renaissance architecture, other than the Bridge of Segovia and the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales.

Philip II moved his court to Madrid in 1561 and transformed the town into a capital city. During the Early Habsburg period, the import of European influences took place, underpinned by the monicker of Austrian style. The Austrian style featured not only Austrian influences but also Italian and Dutch (as well as Spanish), reflecting on the international preeminence of the Habsburgs.[149] During the second half of the 16th century, the use of pointy slate spires in order to top structures such as church towers was imported to Spain from Central Europe.[150] Slate spires and roofs consequently became a staple of the Madrilenian architecture at the time.[151]

Stand out architecture in the city dating back to the early 17th century includes several buildings and structures (most of them attributed to Juan Gómez de Mora) such as the Palace of the Duke of Uceda (1610), the Monastery of La Encarnación (1611–1616); the Plaza Mayor (1617–1619) or the Cárcel de Corte (1629–1641), currently known as the Santa Cruz Palace.[152] The century also saw the construction of the former City Hall, the Casa de la Villa.[153]

The Imperial College church model dome was imitated in all of Spain. Pedro de Ribera introduced Churrigueresque architecture to Madrid; the Cuartel del Conde-Duque, the church of Montserrat, and the Bridge of Toledo are among the best examples.

The reign of the Bourbons during the eighteenth century marked a new era in the city. Philip V tried to complete King Philip II's vision of urbanisation of Madrid. Philip V built a palace in line with French taste, as well as other buildings such as St. Michael's Basilica and the Church of Santa Bárbara. King Charles III beautified the city and endeavoured to convert Madrid into one of the great European capitals. He pushed forward the construction of the Prado Museum (originally intended as a Natural Science Museum), the Puerta de Alcalá, the Royal Observatory, the Basilica of San Francisco el Grande, the Casa de Correos in Puerta del Sol, the Real Casa de la Aduana, and the General Hospital (which now houses the Reina Sofia Museum and Royal Conservatory of Music). The Paseo del Prado, surrounded by gardens and decorated with neoclassical statues, is an example of urban planning. The Duke of Berwick ordered the construction of the Liria Palace.

During the early 19th century, the Peninsular War, the loss of viceroyalties in the Americas, and continuing coups limited the city's architectural development (Royal Theatre, the National Library of Spain, the Palace of the Senate, and the Congress). The Segovia Viaduct linked the Royal Alcázar to the southern part of town.

The list of key figures of madrilenian architecture during the 19th and 20th centuries includes authors such as Narciso Pascual y Colomer, Francisco Jareño y Alarcón, Francisco de Cubas, Juan Bautista Lázaro de Diego, Ricardo Velázquez Bosco, Antonio Palacios, Secundino Zuazo, Luis Gutiérrez Soto, Luis Moya Blanco and Alejandro de la Sota.[154]

From the mid-19th century until the Civil War, Madrid modernised and built new neighbourhoods and monuments. The expansion of Madrid developed under the Plan Castro, resulting in the neighbourhoods of Salamanca, Argüelles, and Chamberí. Arturo Soria conceived the linear city and built the first few kilometres of the road that bears his name, which embodies the idea. The Gran Vía was built using different styles that evolved over time: French style, eclectic, art deco, and expressionist. However, Art Nouveau in Madrid, known as Modernismo did also develop at the turn of the century, in concert with its appearance elsewhere in Europe, including Barcelona and Valencia. Antonio Palacios built a series of buildings inspired by the Viennese Secession, such as the Palace of Communication, the Círculo de Bellas Artes, and the Río de La Plata Bank (now Instituto Cervantes). Other notable buildings include the Bank of Spain, the neo-Gothic Almudena Cathedral, Atocha Station, and the Catalan art-nouveau Palace of Longoria. Las Ventas Bullring was built, as the Market of San Miguel (Cast-Iron style).

Following the Francoist takeover that ensued the end of Spanish Civil war, architecture experienced an involution, discarding rationalism and, eclecticism notwithstanding, going back to an overall rather "outmoded" architectural language, with the purpose of turning Madrid into a capital worthy of the "Immortal Spain".[155] Iconic examples of this period include the Ministry of the Air (a case of herrerian revival) and the Edificio España (presented as the tallest building in Europe when it was inaugurated in 1953).[156][155] Many of these buildings distinctly combine the use of brick and stone in the façades.[155] The Casa Sindical marked a breaking point as it was the first to reassume rationalism, although that relinking to modernity was undertaken through the imitation of the Italian Fascist architecture.[155]

With the advent of Spanish economic development, skyscrapers, such as Torre Picasso, Torres Blancas and Torre BBVA, and the Gate of Europe, appeared in the late 20th century in the city. During the decade of the 2000s, the four tallest skyscrapers in Spain were built and together form the Cuatro Torres Business Area.[157] Terminal 4 at Madrid-Barajas Airport was inaugurated in 2006 and won several architectural awards. Terminal 4 is one of the world's largest terminal areas[158] and features glass panes and domes in the roof, which allow natural light to pass through.

Museums and cultural centres

[edit]

Madrid is considered one of the top European destinations concerning art museums. Best known is the Golden Triangle of Art, located along the Paseo del Prado and comprising three major museums: the Prado Museum, the Reina Sofía Museum, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

The Prado Museum (Museo del Prado) is a museum and art gallery that features one of the world's finest collections of European art, from the 12th century to the early 19th century, based on the former Spanish Royal Collection. It has the best collection of artworks by Goya, Velázquez, El Greco, Rubens, Titian, Hieronymus Bosch, José de Ribera, and Patinir, as well as works by Rogier van der Weyden, Raphael Sanzio, Tintoretto, Veronese, Caravaggio, Van Dyck, Albrecht Dürer, Claude Lorrain, Murillo, and Zurbarán, among others. Some of the standout works exhibited at the museum include Las Meninas, La maja vestida, La maja desnuda, The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Immaculate Conception and The Judgement of Paris.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza) is an art museum that fills the historical gaps in its counterparts' collections: in the Prado's case, this includes Italian primitives and works from the English, Dutch, and German schools, while in the case of the Reina Sofía, the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, once the second largest private collection in the world after the British Royal Collection,[159] includes Impressionists, Expressionists, and European and American paintings from the second half of the 20th century, with over 1,600 paintings.[160]

The Reina Sofía National Art Museum (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía; MNCARS) is Madrid's national museum of 20th-century art and houses Pablo Picasso's 1937 anti-war masterpiece, Guernica. Other highlights of the museum, which is mainly dedicated to Spanish art, include excellent collections of Spain's greatest 20th-century masters including Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Picasso, Juan Gris, and Julio González. The Reina Sofía also hosts a free-access art library.[161]

The National Archaeological Museum of Madrid (Museo Arqueológico Nacional) shows archaeological finds from Prehistory to the 19th century (including Roman mosaics, Greek ceramics, Islamic art and Romanesque art), especially from the Iberian Peninsula, distributed over three floors. An iconic item in the museum is the Lady of Elche, an Iberian bust from the 4th century BC. Other major pieces include the Lady of Baza, the Lady of Cerro de los Santos, the Lady of Ibiza, the Bicha of Balazote, the Treasure of Guarrazar, the Pyxis of Zamora, the Mausoleum of Pozo Moro and a napier's bones. In addition, the museum has a reproduction of the polychromatic paintings in the Altamira Cave.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando) houses a fine art collection of paintings ranging from the 15th to 20th centuries. The academy is also the headquarters of the Madrid Academy of Art.[n. 2]

CaixaForum Madrid is a post-modern art gallery in the centre of Madrid, next to the Prado Museum.[164]

The Royal Palace of Madrid, a massive building characterised by its luxurious rooms, houses rich collections of armours and weapons, as well as the most comprehensive collection of Stradivarius in the world.[165] The Museo de las Colecciones Reales is a future museum intended to host the most outstanding pieces of the Royal Collections part of the Patrimonio Nacional. Located next to the Royal Palace and the Almudena, Patrimonio Nacional has tentatively scheduled its opening for 2021.[166]

The Museum of the Americas (Museo de América) is a national museum that holds artistic, archaeological, and ethnographic collections from the Americas, ranging from the Paleolithic period to the present day.[167]

Other notable museums include the National Museum of Natural Sciences (the Spain's national museum of natural history),[168] the Naval Museum,[169] the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales (with many works of Renaissance and Baroque art, and Brussels tapestries inspired by paintings of Rubens),[170] the Museum of Lázaro Galdiano (housing a collection specialising in decorative arts, featuring a collection of weapons that features the sword of Pope Innocent VIII),[171] the National Museum of Decorative Arts,[172] the National Museum of Romanticism (focused on 19th century Romanticism),[173] the Museum Cerralbo,[174] the National Museum of Anthropology (featuring as highlight a Guanche mummy from Tenerife),[175] the Sorolla Museum (focused in the namesake Valencian Impressionist painter,[176] also including sculptures by Auguste Rodin, part of Sorolla's personal effects),[177] or the History Museum of Madrid (housing pieces related to the local history of Madrid), the Wax Museum of Madrid, and the Railway Museum (located in the building that was once the Delicias Station).

Major cultural centres in the city include the Fine Arts Circle (one of Madrid's oldest arts centres and one of the most important private cultural centres in Europe, hosting exhibitions, shows, film screenings, conferences and workshops), the Conde Duque cultural centre or the Matadero Madrid, a cultural complex (formerly an abattoir) located by the river Manzanares. The Matadero, created in 2006 with the aim of "promoting research, production, learning, and diffusion of creative works and contemporary thought in all their manifestations", is considered the third most valued cultural institution in Madrid among art professionals.[178]

Language

[edit]The usual language in Madrid is Peninsular Spanish. It is in the transition between northern and southern dialects. Typical features are:

- Yeísmo, calló and cayó sound alike among all social classes.[179] According to Alonso Zamora Vicente, yeísmo has extended from Madrid across Spain.[179]

- Aspiration of implosive /s/.[180]

- Frequent ellision of final /d/ ([maˈðɾi]) and devoicing /θ/ ([maˈðɾiθ] ) coexist with the standard preservation ([maˈðɾið] ) realised with varying degrees of relaxation.[8]

- leísmo, laísmo and loísmo. According to Samuel Gili Gaya, in Madrid speech, pronoun le is specialized in the masculine and pronoun la in the feminine, for direct and indirect objects.[181]

The arrival to Madrid of a substantial number of immigrants from Latin America (such as Ecuadorians) has induced processes of dialectal convergence and divergence in the city.[182]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Madrid youth created their own slang, Cheli.[183]

Literature

[edit]Madrid has been one of the great centres of Spanish literature. Some of the most distinguished writers of the Spanish Golden Century were born in Madrid, including Lope de Vega (author of Fuenteovejuna and The Dog in the Manger), who reformed the Spanish theatre, a project continued by Calderon de la Barca (author of Life is a Dream). Francisco de Quevedo, who criticised the Spanish society of his day, and author of El Buscón, and Tirso de Molina, who created the character Don Juan, were born in Madrid. Cervantes and Góngora also lived in the city, although they were not born there. The Madrid homes of Lope de Vega, Quevedo, Gongora, and Cervantes still exist, and they are all in the Barrio de las Letras (Literary Neighborhood). Other writers born in Madrid in later centuries have been Leandro Fernandez de Moratín, Mariano José de Larra, Jose de Echegaray (Nobel Prize in Literature), Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Dámaso Alonso, Enrique Jardiel Poncela and Pedro Salinas.

The "Barrio de las Letras" owes its name to the intense literary activity taking place there during the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of the most prominent writers of the Spanish Golden Age lived here, such as Lope de Vega, Quevedo, and Góngora, and it contained the Cruz and Príncipe Theatres, two of the most important in Spain. At 87 Calle de Atocha, on the northern end of the neighborhood, was the printing house of Juan de la Cuesta, where the first edition of Don Quixote was typeset and printed in 1604. Most of the literary routes are articulated[further explanation needed] along the Barrio de las Letras, where you can find scenes from novels of the Siglo de Oro and more recent works like "Bohemian Lights".[further explanation needed] Although born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, realist writer Benito Pérez Galdós made Madrid the setting for many of his stories; there is a giidebook to the Madrid of Galdós (Madrid galdosiano).[184]

Madrid is home to the Royal Spanish Academy, the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language, which governs, with statutory authority, over Spanish,[185] preparing, publishing, and updating authoritative reference works on it. The academy's motto (lema, in Spanish) states its purpose: it cleans the language, stabilizes it, and gives it brilliance ("Limpia, fija y da resplendor"). Madrid is also home to another international cultural institution, the Instituto Cervantes, whose task is the promotion and teaching of the Spanish language as well as the dissemination of the culture of Spain and Hispanic America. The National Library of Spain is the largest major public library in Spain. The library's collection consists of more than 26,000,000 items, including 15,000,000 books and other printed materials, 30,000 manuscripts, 143,000 newspapers and serials, 4,500,000 graphic materials, 510,000 music scores, 500,000 maps, 600,000 sound recording, 90,000 audiovisuals, 90,000 electronic documents, and more than 500,000 microforms.[186]

Cuisine

[edit]The Madrilenian cuisine has received plenty of influences from other regions of Spain and its own identity actually relies in its ability to assimilate elements from the immigration.[187]

The cocido madrileño, a chickpea-based stew, is one of the most emblematic dishes of the Madrilenian cuisine.[188] The callos a la madrileña is another traditional winter specialty, usually made of cattle tripes.[189] Other offal dishes typical in the city include the gallinejas[189] or grilled pig's ear.[190] Fried squid has become a culinary specialty in Madrid, often consumed in sandwich as bocata de calamares.[189]

Other generic dishes commonly accepted as part of the Madrilenian cuisine include the potaje, the sopa de ajo (Garlic soup), the Spanish omelette, the besugo a la madrileña (bream), caracoles a la madrileña (snails, sp. Cornu aspersum) or the soldaditos de Pavía, the patatas bravas (consumed as snack in bars) or the gallina en pepitoria (hen or chicken cooked with the yolk of hard-boiled eggs and almonds) to name a few.[191][192][187]

Traditional desserts include torrijas (a variant of French toast consumed during Easter)[189][193] and bartolillos.[192]

Nightlife

[edit]

Madrid is an international hub of highly active and diverse nightlife with bars, dance bars and nightclubs staying open well past midnight.[194] Madrid is reputed to have a "vibrant nightlife".[195] Some of the highlight bustling locations include the surroundings of the Plaza de Santa Ana, Malasaña and La Latina (particularly near the Cava Baja).[195] It is one of the city's main attractions with tapas bars, cocktail bars, clubs, jazz lounges, live music venues and flamenco theatres. Most nightclubs liven up by 1:30 a.m.and stay open until at least 6 a.m.[195]

Nightlife flourished in the 1980s while Madrid's mayor Enrique Tierno Galván (PSOE) was in office, nurturing the cultural-musical movement known as La Movida.[196] Nowadays, the Malasaña area is known for its alternative scene.

The area of Chueca has also become a hot spot in the Madrilenian nightlife, especially for the gay population. Chueca is known as gay quarter, comparable to the Castro District in San Francisco.[197]

Bohemian culture

[edit]

The city has venues for performing alternative art and expressive art. They are mostly located in the centre of the city, including in Ópera, Antón Martín, Chueca and Malasaña. There are also several festivals in Madrid, including the Festival of Alternative Art, and the Festival of the Alternative Scene.[198][199][200][201]

The neighbourhood of Malasaña, as well as Antón Martín and Lavapiés, hosts several bohemian cafés/galleries. These cafés are typified with period or retro furniture or furniture found on the street, a colourful, nontraditional atmosphere inside, and usually art displayed each month by a new artist, often for sale. Cafés include the retro café Lolina and bohemian cafés La Ida, La Paca and Café de la Luz in Malasaña, La Piola in Huertas and Café Olmo and Aguardiente in Lavapiés.

In the neighbourhood of Lavapiés, there are also "hidden houses", which are illegal bars or abandoned spaces where concerts, poetry readings and[202][203][204] the famous Spanish botellón (a street party or gathering that is now illegal but rarely stopped).

Classical music and opera

[edit]

The Auditorio Nacional de Música [205] is the main venue for classical music concerts in Madrid. It is home to the Spanish National Orchestra, the Chamartín Symphony Orchestra[206] and the venue for the symphonic concerts of the Community of Madrid Orchestra and the Madrid Symphony Orchestra. It is also the principal venue for orchestras on tour playing in Madrid.

The Teatro Real is the main opera house in Madrid, located just in front of the Royal Palace, and its resident orchestra is the Madrid Symphony Orchestra.[207] The theatre stages around seventeen opera titles (both own productions and co-productions with other major European opera houses) per year, as well as two or three major ballets and several recitals.

The Teatro de la Zarzuela is mainly devoted to Zarzuela (the Spanish traditional musical theatre genre), as well as operetta and recitals.[208][209] The resident orchestra of the theatre is the Community of Madrid Orchestra.

The Teatro Monumental is the concert venue of the RTVE Symphony Orchestra.[210]

Other concert venues for classical music are the Fundación Joan March and the Auditorio 400, devoted to contemporary music.

Feasts and festivals

[edit]San Isidro

[edit]

The local feast par excellence is the Day of Isidore the Laborer (San Isidro Labrador), the patron Saint of Madrid, celebrated on 15 May. It is a public holiday. According to tradition, Isidro was a farmworker and well manufacturer born in Madrid in the late 11th century, who lived a pious life and whose corpse was reportedly found to be incorrupt in 1212. Already very popular among the madrilenian people, as Madrid became the capital of the Hispanic Monarchy in 1561 the city council pulled efforts to promote his canonization; the process started in 1562.[211] Isidro was beatified in 1619 and the feast day set on 15 May[212] (he was finally canonized in 1622).[213]

On 15 May the Madrilenian people gather around the Hermitage of San Isidro and the Prairie of San Isidro (on the right-bank of the Manzanares) often dressed with checkered caps (parpusas) and kerchiefs (safos)[214] characteristic of the chulapos and chulapas, dancing chotis and pasodobles, eating rosquillas and barquillos.[215]

LGBT pride

[edit]

The Madrilenian LGBT Pride has grown to become the event bringing the most people together in the city each year[216] as well as one of the most important Pride celebrations worldwide.[217]

Madrid's Pride Parade began in 1977, in the Chueca neighbourhood, which also marked the beginning of the gay, lesbian, transgender, and bisexual rights movement after being repressed for forty years in a dictatorship.[218] This claiming of LGBT rights has allowed the Pride Parade in Madrid to grow year after year, becoming one of the best in the world. In 2007, this was recognised by the European Pride Organisers Association (EPOA) when Madrid hosted EuroPride. It was hailed by the then President of the EPOA as "the best EuroPride in history".[219] In 2017, Madrid celebrated the 40th anniversary of their first Pride Parade by hosting the WorldPride Madrid 2017. Numerous conferences, seminars and workshops as well as cultural and sports activities took place at the festival, the event being a "kids and family pride" and a source of education. More than one million people attended the pride's central march.[220] The main purpose of the celebration was presenting Madrid and the Spanish society in general as a multicultural, diverse, and tolerant community.[218] The 2018 Madrid Pride roughly had 1.5 million participants.[135]p. 34

Since Spain legalised same-sex marriage in July 2005,[221] Madrid has become one of the largest hot spots for LGBT culture. With about 500 businesses aimed toward the LGBT community, Madrid has become a "Gateway of Diversity".[219]

Other

[edit]

Despite often being labelled as "having no tradition" by foreigners,[222] the Carnival was popular in Madrid already in the 16th century. However, during the Francoist dictatorship the carnival was under government ban and the feasts suffered a big blow.[222][223] It has been slowly recovering since then.

Other signalled days include the regional day (2 May) commemorating the Dos de Mayo Uprising (a public holiday), the feasts of San Antonio de la Florida (13 June), the feast of the Virgen de la Paloma (circa 15 August) or the day of the co-patron of Madrid, the Virgin of Almudena (9 November), although the latter's celebrations are rather religious in nature.[224]

The most important musical event in the city is the Mad Cool festival; created in 2016, it reached an attendance of 240,000 during the three-day long schedule of the 2018 edition.[135]p. 33

Bullfighting

[edit]Madrid hosts the largest plaza de toros (bullring) in Spain, Las Ventas, established in 1929. Las Ventas is considered by many to be the world centre of bullfighting and has a seating capacity of almost 25,000. Madrid's bullfighting season begins in March and ends in October. Bullfights are held every day during the festivities of San Isidro (Madrid's patron saint) from mid May to early June, and every Sunday, and public holiday, the rest of the season. The style of the plaza is Neo-Mudéjar. Las Ventas also hosts music concerts and other events outside of the bullfighting season. There is great controversy in Madrid with bullfighting.[failed verification][225]

Sport

[edit]Football

[edit]

Real Madrid, founded in 1902, compete in La Liga and play their home games at the Santiago Bernabéu Stadium. The club is one of the most widely supported teams in the world and their supporters are referred to as Madridistas or Merengues (Meringues). Real's supporters in Madrid are often believed to be constituted principally of members of the middle classes, however, this claim is in dispute and has not been proved. It has also been suggested that a large proportion of Real Madrid's fans are members of the working class.[226] The club was selected as the best club of the 20th century, being the fifth most valuable sports club in the world and the most successful Spanish football club with a total of 104 official titles (this includes a record 15 European Cups and a record 36 La Liga trophies).

Atlético Madrid, founded in 1903, also compete in La Liga and play their home games at the Metropolitano Stadium. The club is well-supported in the city, having the third national fan base in Spain and their supporters are referred to as Atléticos or Colchoneros (The Mattressers). Atlético is believed to draw its support mostly from working class citizens.[227] The club is considered an elite European team, having won three UEFA Europa League titles and reached three European Cup finals. Domestically, Atletico have won eleven league titles and ten Copa del Reys.

Rayo Vallecano, founded in 1924, are the third most important football team of the city, based in the Vallecas neighborhood. They currently compete in La Liga, having secured promotion in 2021. The club's fans tend to be very left-wing and are known as Buccaneers.

Getafe CF, founded in 1983, also compete in La Liga and play their home games at the Estadio Coliseum. The club was promoted to La Liga for the first time in 2004, and participated in the top level of Spanish football for twelve years between 2004 and 2016, and again since 2017.

CD Leganés, founded in 1928, compete in Segunda Division and play their home games at the Estadio Municipal de Butarque. In the 2015–16 season, for the first time in their history, Leganés earned promotion to La Liga. They remained in the top flight for four seasons, reaching a peak of 13th in 2018–19, before relegation in the last game of the following season, a 2–2 home draw with Real Madrid.

Madrid hosted five European Cup/Champions League finals, four at the Santiago Bernabéu, and the 2019 final at the Metropolitano. The Bernabéu also hosted the Euro 1964 Final (which Spain won) and 1982 FIFA World Cup Final.

Basketball

[edit]

Real Madrid Baloncesto, founded in 1931, compete in Liga ACB and play their home games at the Palacio de Deportes (WiZink Center). Real Madrid's basketball section, similar to its football team, is the most successful team in Europe, with a record 11 EuroLeague titles. Domestically, they have clinched a record 36 league titles and a record 28 Copa del Reys.

Club Baloncesto Estudiantes, founded in 1948, compete in LEB Oro and also play their home games at the Palacio de Deportes (WiZink Center). Until 2021, Estudiantes was one of only three teams that have never been relegated from Spain's top division. Historically, its achievements include three cup titles and four league runners-up placements.

Madrid has hosted six European Cup/EuroLeague finals, the last two at the Palacio de Deportes. The city also hosted the final matches for the 1986 and 2014 FIBA World Cups, and the EuroBasket 2007 final (all held at the Palacio de Deportes).

Events

[edit]

The main annual international event in cycling, the Vuelta a España (La Vuelta), is one of the three worldwide prestigious three-week-long Grand Tours, and its final stages takes place in Madrid on the first Sunday of September. In tennis, the city hosts Madrid Open, both male and female versions, played on clay court. The event is part of the nine ATP Masters 1000 and nine WTA 1000 tournaments. It is held during the first week of May in the Caja Mágica. Additionally, Madrid hosts the finals of the major tournament for men's national teams, Davis Cup, since 2019.

Formula 1