St Cadoc's Church, Raglan

| Church of St Cadoc, Raglan, Monmouthshire | |

|---|---|

| Church of St Cadoc | |

St Cadoc's | |

| 51°45′53″N 2°51′05″W / 51.7647°N 2.8514°W | |

| Location | Raglan, Monmouthshire |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founded | C13th-C14th century |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 18 November 1980 |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Monmouth |

| Archdeaconry | Monmouth |

| Deanery | Raglan/Usk |

| Parish | Raglan |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | The Rev'd Kevin Hasler |

St Cadoc's Church, Raglan, Monmouthshire, Wales, is the parish church of the village of Raglan, situated at a cross-roads in the centre of the village. Built originally by the Clare and Bluet families in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was rebuilt and expanded by the Herbert's of Raglan Castle in the fifteenth century. In the nineteenth century the church was subject to a major restoration by Thomas Henry Wyatt.

Built in the Decorated style, the church is a Grade II* listed building.

History

[edit]Sir Joseph Bradney, the Monmouthshire antiquarian, described the church in his multi-volume A History of Monmouthshire from the Coming of the Normans into Wales down to the Present Time. He said the earliest church on the site was founded by Saint David, the patron saint of Wales,[1] and that "for some reason which is not apparent the modern ecclesiastical authorities consider Cattwg (Cadoc) to be the patron saint".[1] Hando also said there was a controversy as to the dedication, and said a will dated 1494 references "Sancta Cadoci ville de Raglan."[2] The present church was probably begun by the de Clare family, earliest Lords of Raglan,[1] and completed in the fourteenth century by the Bluets.[1] The church was greatly expanded by the Herberts of Raglan Castle, and by their successors, the Somersets, Earls and Marquesses of Worcester and Dukes of Beaufort.[1] The Beaufort (North) Chapel, constructed by the Somersets, contains three monumental tombs of the Earls of Worcester, hereditary Lords of Raglan and of Raglan Castle in the Middle Ages, with their remains interred within the crypt below the Beaufort Chapel, the side chapel to the north of the nave.[3] These monuments were mutilated by Parliamentarian troops during the English Civil War, they represent William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester, Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Hastings.[3]

Charles Somerset, Marquess of Worcester, who died in a coaching accident between Raglan and Monmouth, is also buried in the church.[4] Bradney records a tablet placed in the chapel by Henry Somerset, 8th Duke of Beaufort in 1868, which details all of the Somerset interments.[1]

The church tower clock is notable for having only three faces; the Monmouthshire writer Fred Hando records that the benefactor, Miss Anna Maria Bosanquet, declined to provide a fourth face, pointing in the direction of Raglan Station, having fallen out with the station's owners.[a][2]

There are also a number of memorials to the Barons Raglan, of nearby Cefntilla Court, including a stained glass window "commemorating the military exploits of FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan" in the Crimean War.[3]

Architecture and description

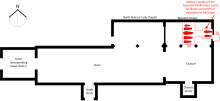

[edit]The chancel and the nave date from the fourteenth century, whilst the "fine, tall" west tower is fifteenth century.[6] The architectural historian John Newman considers the tower's diagonal buttresses "unusual" and suggests their styling dates them to similar work being carried out at Raglan Castle in the 1460s.[3] The Beaufort (North) Chapel, the resting place of many of the lords of Raglan, dates from the middle sixteenth century.[3] The font is original and was returned to the church in the 1920s, after being discovered buried in his garden by the then vicar.[5]

The rest dates predominantly from the mid-Victorian restoration carried out by Thomas Henry Wyatt in 1867–8.[3] All of the church's stained glass dates from this time. The restoration was carried out for Henry Somerset, 8th Duke of Beaufort and included the construction of the Lady Chapel.[7] Re-roofing of Wyatt's nineteenth century roof in 2016 revealed the late-medieval "wagon-roof", a type of roofing common in medieval Monmouthshire.[8]

The churchyard contains the "unusually fine" base and stump of a medieval cross.[3]

Vicars since 1560

[edit]- 1560, John Gallin (Gwillim)

- 1635, William Rogers

- 1640, William Davies

- 1661, John Davies

- 1678, Rice Morris

- 1682, William Hopkins

- 1709, Richard Tyler, B.A.

- 1715, David Price

- 1746, John Leach. B.A.

- 1781, Thomas Leach. (died 1796 at Blakeney, Glos.)

- 1796, Charles Phillips, B.A.

- 1818, William Powell, M.A.

- 1866, Arthur Montague Wyatt

- 1874, Henry Plantagenet Somerset, M.A.

- 1893, Charles Mathew Perkins, M.A.

- 1903, Robert Shelley Plant.

- 1924, David James Sproule, B.A.

- 1928, Thomas Wright, B.A.

- 1939, Charles Duck, L. Div.

- 1952, William Joseph Price

- 1958, Arthur Vernon Blake, B.A.

- 1975, Peter Charles Gwynne Gower

- 1991, Simon Llewellyn Guest

- 2005, Joan Wakeling

- 2014, The Rev'd Canon Tim Clement[9]

Burials in the Somerset Crypt

[edit]Underneath the church is the Somerset family crypt. A tablet was erected in the church in 1868 by the 8th Duke of Beaufort stating:[10]

In the vaults beneath are interred:

- William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester, K.G. died 21st February, 1589.

- Edward Somerset, 4th Earl of Worcester, K.G. died 3rd March 1627.

- Elizabeth, his wife, daughter of Francis Hardinge, Earl of Huntingdon 1621.

- Edward, 6th Earl and 2nd Marquis of Worcester, died 3rd April 1667.

- Mary, daughter of Edward, 6th Earl, and his wife, died in infancy.

- Charles, 2nd son of Henry, 7th Earl, 3rd Marquis, and 1st Duke of Beaufort, died 13 July 1698.

- Edward, 3rd son of the above, died in infancy.

- Henry, 4th son of the above, died 1st April, 1667.

- Elizabeth, elder daughter of the above.

- Rebecca, wife of Charles, Marquis of Worcester, eldest son of Henry, 1st Duke of Beaufort, [died] July 27th [1712] aged 44.

- Mary, daughter of Charles, 2nd Duke of Beaufort ,[b] died in her infancy, 1685.

- John, 3rd son of Charles, 2nd Duke of Beaufort, died 31st December, 1704.

Other than interments, the vault is known to have been disturbed on at least 4 occasions:

- During the English Civil War, (1642 - 1651) Roundheads opened the vault and destroyed some tombs. The remains of 3 effigies destroyed in this action were moved to the Beaufort Chapel.[10]

- At some point prior the 1797 publication of "Historical and Descriptive Account of the Present State of Ragland Castle", Charles Heath, a printer and writer from Monmouth, twice visited the church and found the chancel floor collapsed giving access to the two rooms which make up the vault. He surveyed the vault and documented his findings in the same work. He discovered seven lead coffin linings: five in the main room and two in a recess. Additionally, he discovered the remains of the wooden caskets and the ornamental metalwork, strewn across the floor, either from the previous desecration of the roundheads, or from natural decomposition of the wooden coffins.[10]

- On 11 December 1860, Mr Osmond A Wyatt, the land agent for the Monmouth estates, opened the vault with "four strong burning lamps", again encountering seven lead coffin linings as before, but noting that one of the lead coffin linings appears to have been opened, and that the detritus on the floor included bones, either from the Roundheads desecration, or from the decomposition of coffins which were not lead lined.[10] This survey was a precursor to the excavation of 1861.

- On 4 January 1861, Bennet Woodcroft, of the London Patent Office, his companion John Macgregor, a philanthropist, traveller and writer, Wyatt, the land agent, a carpenter, three labourers, the sexton and clerk opened the crypt in search of a model steam engine which Edward, the second Marquis, specified should be buried with him. They opened two of the seven coffin linings but did not find the model.[10]

The details of the seven extant coffins observed at the documented openings of the crypt are in the table below:

| Coffin Number and Dimensions (from Wyatt's diagram) | Heath's 1797 Interpretation | Wyatt's 1860 Interpretation | Woodcroft/McGregor's 1861 Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffin 1 - 4'1" by 1'2" | Lord John Somerset | A child's coffin. | |

| Coffin 2 - 6'5" by 1'8" | Lord Charles Somerset | ||

| Coffin 3 - 6'7" by 2'2.5" | Lady Granville - "Coffin 8 feet long - Three Wide - Two feet 3 inches deep." | Noted less impressive dimensions than Heath, commenting "a huge coffin in lead placed somewhat askew with a brass plate resting on it but not attached, telling us that a Lady Somerset was interred within."[10] | Having failed to find the model in their initial inspection of coffin 7, McGregor suspected coffin 2 may be the Marquis' coffin wrongly attributed to Lady Granville, so opened to confirm the sex of the deceased. "The lead was therefore cut and folded back and underneath there was found a carefully placed ceiling of beautifully glass-like green wax which seemed quite untouched by decay." They then cut out a section of wood and saw "that the two breasts of a female lying in state confirmed the supposition that the plate was correctly placed on this coffin". McGregor cut open the head covering and "the mouth was soon disclosed and five or six long and rather misshapen teeth appeared. The lower jaw was much separated from the other and I raised it in order to search carefully below for any necklace or other ornament which might be buried there".[10] |

| Coffin 4 - 5'10" by 1'4" | Edward Marquis of Worcester, noting the transcription "Illustrissimi Principis Edwardi, Marchionis et Comitatis Wigorniae, Comitis de Glamorgan, Baronis Herbert de Ragland, et qui obiit apud Londini tertio die Aprilis, A. Dno. MDCLXVII. Loyal to his prince, a true lover of his country, and to his Friend most constant."[10] | Coffin showed evidence of having been previously opened, with two triangular cuts at the head shown on the plan. The inscription was not present on this coffin, and consequently this was interpreted as not being the Marquis' coffin.[10] | |

| Coffin 5 - 2'8" by 8" | Lady Mary Somerset | ||

| Coffin 6 - 5'7" by 1'3" | Ancient Figure - Buried “according to ancient mode of burial, viz., the exact shape of the body at full length, with only the eyes, nose and mouth formed on the metal”.[10] | ||

| Coffin 7 - 6'6" by 1'9" | In early editions "Marchioness of Worcester". In later editions, simply "Anonymous". "Wrapped in lead, devoid of any form or care whatever."[10] | "Baffled by the absence of the figure devoid of any care or form whatever", noted the inscription that Heath attributed to Coffin 4 to this coffin, meaning this was interpreted as the Edward, 2nd Marquis' coffin. | Coffin opened and documented by McGregor, "the lead on the outside was dry and well preserved, and when a part of it had been cut and rolled back some holes were made with the bit and brace in the elmwood cover, which allowed a few smart blows with the chisel to take out a small piece of wood." The foot of the coffin was opened and the 6 or 7 layers of "strong linen" were cut open to reveal "two legs inside with skin very white and not very much shrunken". Outside the linen they found matter "exactly like the slush in an Irish bog and emitting a strong but not pungent or disagreeable odour". The head of the coffin was then opened, although "out of respect for the remains of the mighty dead we did not open the cloth over the face".[10]

They later returned to this coffin, "making a long cut through the stiff close shroud and inserting the axe point in the edge we lifted up the naked body of the renowned Marquis of Worcester. The hands were crossed over the lower part of the stomach, the right hand being uppermost and bound to the other with a lanyard of yarn rope. The skin and flesh were soft and a little shrunken and the nails were long, beautifully shaped and perfectly preserved. There was a good deal of reddish hair on the body. No sign of any substance metal wood or other hard matter being in the coffin could be observed. I was determined to make a thorough search when I was about it and therefore sending for a large screwdriver which was nearly two feet long I probed carefully round the whole body at intervals of about an inch to see if under any part or concealed by the dark mud like matter there might haply be any small metallic ring to indicate the model we were in search of."[10] |

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ John Guy and Ewart Smith, in their study Ancient Gwent Churches, suggest that Miss Bosanquet's actions arose from a generalised dislike of railway development rather than a particularised dislike of the owners of Raglan Station.[5]

- ^ It is stated elsewhere that the 2nd Duke of Beaufort was Charles' son, Henry, inheriting the title directly from the grandfather who outlived the father. The application of the style "Duke of Beaufort" to Charles would appear to be an honorary title, as he died in a coaching accident before his succession to the Dukedom.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Bradney 1992, pp. 33–8.

- ^ a b Hando 1964, pp. 69–71.

- ^ a b c d e f g Newman 2000, pp. 488–9.

- ^ Members Constituencies Parliaments Surveys. "Charles Somerset, Marquess of Worcester (1660–98)". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ a b Guy & Smith 1980, p. 58.

- ^ Davies 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Cadw. "St Cadoc's Church, Raglan (Grade II*) (2100)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "St Cadoc, Raglan (307349)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ St Cadoc's Church Guide. Mrs Horatia Durant. 1975

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hewish, John (1982). "The Raid on Raglan: Sacred Ground and Profane Curiosity". The British Library Journal. 8 (2): 182–198. JSTOR 42554164 – via JSTOR.

References

[edit]- Bradney, Joseph (1992). The Hundred of Raglan. A History of Monmouthshire. Vol. 2 (Part 1). London: Academy Books. ISBN 978-1-873361-09-2. OCLC 25717697.

- Davies, E.T. (1977). A Guide to the Ancient Churches of Gwent. Pontypool, Wales: Hughes & Son Ltd. ISBN 0950049085. OCLC 877397812.

- Guy, John; Smith, Ewart (1980). Ancient Gwent Churches. Newport: The Starling Press. OCLC 656714152.

- Hando, Fred (1964). Here and There in Monmouthshire. Newport: R. H. Johns. OCLC 30295639.

- Newman, John (2000). Gwent/Monmouthshire. The Buildings of Wales. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071053-1.

External links

[edit]- [1] St Cadoc's Church, Raglan, Wales