Oak Bay, British Columbia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Oak Bay | |

|---|---|

| The Corporation of the District of Oak Bay[1] | |

| |

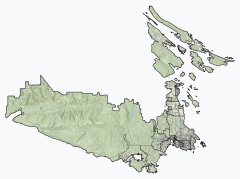

Location of Oak Bay within the Capital Regional District | |

| Coordinates: 48°25′33″N 123°19′05″W / 48.42583°N 123.31806°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Regional district | Capital |

| Incorporated | 1906 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kevin Murdoch |

| • Governing Body | Oak Bay Municipal Council |

| • MP | Laurel Collins (NDP) |

| • MLA | Murray Rankin (BC NDP) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 10.52 km2 (4.06 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 34 m (112 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 17,990 |

| • Density | 1,710.1/km2 (4,429/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Area code(s) | 250, 778 |

| Website | www |

Oak Bay is a municipality incorporated in 1906 that is located on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, in the Canadian province of British Columbia. It is one of thirteen member municipalities of the Capital Regional District, and is bordered to the west by the city of Victoria and to the north by the district of Saanich. It is an eastern residential suburb of Victoria.

History

[edit]

Oak Bay is part of the traditional territories of the Coast Salish people of the Songhees First Nation. The people that came and went in the millennia before are unknown. Evidence of their ancient settlements has been found along local shores, including Willows Beach, where an ancient Lkwungen seaport known as Sitchanalth was centred around the mouth of the river commonly known as Bowker Creek.[3] Sitchanalth is hypothesized to have been destroyed by the great Tsunami of 930 AD.[4] Much of this neighbourhood is built upon an Indigenous burial ground.[5]

Oak Bay takes its name from the Garry oak tree, which is found throughout the region, and also the name of the large bay on the eastern shore of the municipality, fronting onto Willows Beach.

John Tod, in 1850, built on a 109-acre (44 ha) farm that is today the oldest continuously-occupied home in Western Canada. Tod was the Chief Fur Trader for the Hudson's Bay Company for Kamloops, one of the original appointed members of BC's Legislative Council.[6][7][8]

Originally developed as a middle class streetcar suburb of Victoria, Oak Bay was incorporated as a municipality in 1906. Its first Council included Francis Rattenbury, the architect who designed the Legislative Buildings and Empress Hotel located on the inner harbour in Victoria. Rattenbury's own home on Beach Drive is now used as the junior campus for Glenlyon Norfolk School. In 1912, the former farm lands of the Hudson's Bay Company were subdivided to create the Uplands area, but development was hampered by the outbreak of World War I. After the war, development of expensive homes in the Uplands was accompanied by the construction of many more single-family dwellings in the Estevan, Willows and South Oak Bay neighbourhoods.

The Victoria Golf Club is located in South Oak Bay. It was founded in 1893, and is the second oldest golf course west of the Great Lakes. It is a 6,120 yard links course on the ocean side, and claims to be the oldest golf course in Canada still on its original site. The course is reported to be haunted.[7]

The Royal Victoria Yacht Club was formed on June 8, 1892, and moved in 1912 to its current location, at the location of the old Hudson's Bay Company cattle wharf.

In 1925, the Victoria Cougars won the Stanley Cup at the Patrick Arena in Oak Bay, defeating the Montreal Canadiens in four games.[9] The arena was soon after destroyed by fire in 1929. Nowadays, the Victoria Cougars are the Detroit Red Wings of the National Hockey League.

The Oak Bay Marina, built in 1962, was officially opened in April 1964. It replaced the Oak Bay Boat House built in 1893. The breakwater was built in 1959 and funded by the federal government.

There have reportedly been sightings of a sea monster known as the Cadborosaurus off Oak Bay, with both reports dating back to before European settlement in the area.[10]

Geography

[edit]Neighbourhoods:

- North Oak Bay

- South Oak Bay

- Uplands

- Henderson

- Gonzales

- Estevan[11]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for University of Victoria (Oak Bay / Saanich) WMO ID: 71783; coordinates 48°27′25″N 123°18′17″W / 48.45694°N 123.30472°W; elevation: 60.1 m (197 ft); 1991-2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 19.6 | 16.6 | 21.9 | 25.3 | 31.3 | 35.2 | 40.4 | 35.0 | 33.4 | 31.1 | 20.5 | 20.9 | 40.4 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.5 (94.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.9 (44.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

| Record low wind chill | −15.4 | −11.8 | −9.0 | −1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −3.3 | −12.4 | −14.5 | −15.4 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 109.6 (4.31) |

59.6 (2.35) |

52.6 (2.07) |

35.6 (1.40) |

29.2 (1.15) |

19.7 (0.78) |

10.7 (0.42) |

15.6 (0.61) |

30.4 (1.20) |

77.2 (3.04) |

123.2 (4.85) |

97.8 (3.85) |

661.2 (26.03) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 18.7 | 15.1 | 17.2 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 11.1 | 17.8 | 21.4 | 19.3 | 164.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 83.3 | 75.5 | 70.5 | 63.8 | 60.8 | 58.0 | 55.5 | 57.8 | 65.7 | 76.6 | 81.9 | 82.8 | 69.3 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[12] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Gonzales Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada (1971-2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 13.8 | 16.0 | 18.3 | 22.4 | 29.1 | 33.8 | 36.1 | 35.0 | 32.3 | 24.7 | 19.7 | 15.1 | 36.1 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

20.6 (69.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.5 (85.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.3 (50.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.4 (6.1) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Record low wind chill | −22.0 | −19.0 | −14.0 | −5.0 | −2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | −9.0 | −21.0 | −27.0 | −27.0 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.3 (3.71) |

71.7 (2.82) |

46.5 (1.83) |

28.5 (1.12) |

25.8 (1.02) |

20.7 (0.81) |

14.0 (0.55) |

19.7 (0.78) |

27.4 (1.08) |

51.2 (2.02) |

98.9 (3.89) |

108.9 (4.29) |

607.6 (23.92) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 85.2 (3.35) |

68.1 (2.68) |

45.3 (1.78) |

28.5 (1.12) |

25.8 (1.02) |

20.7 (0.81) |

14.0 (0.55) |

19.7 (0.78) |

27.4 (1.08) |

51.1 (2.01) |

95.5 (3.76) |

101.9 (4.01) |

583.2 (22.95) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.7 (3.8) |

3.5 (1.4) |

1.1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

4.1 (1.6) |

7.8 (3.1) |

26.3 (10.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.0 | 15.4 | 14.5 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 17.5 | 141.9 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.6 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 11.9 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 129.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.82 | 1.9 | 7.81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74.1 | 93.7 | 149.5 | 201.5 | 266.6 | 273.8 | 327.8 | 297.3 | 204.1 | 153.4 | 83.1 | 68.7 | 2,193.6 |

| Source: Environment Canada[13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Oak Bay had a population of 17,990 living in 7,807 of its 8,168 total private dwellings, a change of -0.6% from its 2016 population of 18,094. With a land area of 10.52 km2 (4.06 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,710.1/km2 (4,429.1/sq mi) in 2021.[2]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population counts are not adjusted for boundary changes. Source: Statistics Canada | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnicity

[edit]| Panethnic group |

2021[14] | 2016[15] | 2011[16] | 2006[17] | 2001[18] | 1996[19] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |||

| European[a] | 15,040 | 85.26% | 15,355 | 87.87% | 15,515 | 89.24% | 16,200 | 91.6% | 16,030 | 91.68% | 16,240 | 92.3% | ||

| East Asian[b] | 1,110 | 6.29% | 1,080 | 6.18% | 810 | 4.66% | 645 | 3.65% | 1,000 | 5.72% | 845 | 4.8% | ||

| South Asian | 370 | 2.1% | 285 | 1.63% | 325 | 1.87% | 180 | 1.02% | 120 | 0.69% | 205 | 1.17% | ||

| Indigenous | 345 | 1.96% | 255 | 1.46% | 190 | 1.09% | 260 | 1.47% | 120 | 0.69% | 90 | 0.51% | ||

| Southeast Asian[c] | 250 | 1.42% | 190 | 1.09% | 155 | 0.89% | 185 | 1.05% | 75 | 0.43% | 10 | 0.06% | ||

| Latin American | 120 | 0.68% | 95 | 0.54% | 45 | 0.26% | 65 | 0.37% | 45 | 0.26% | 35 | 0.2% | ||

| Middle Eastern[d] | 115 | 0.65% | 115 | 0.66% | 85 | 0.49% | 80 | 0.45% | 10 | 0.06% | 80 | 0.45% | ||

| African | 100 | 0.57% | 55 | 0.31% | 60 | 0.35% | 25 | 0.14% | 70 | 0.4% | 85 | 0.48% | ||

| Other/Multiracial[e] | 180 | 1.02% | 45 | 0.26% | 75 | 0.43% | 35 | 0.2% | 20 | 0.11% | 10 | 0.06% | ||

| Total responses | 17,640 | 98.05% | 17,475 | 96.58% | 17,385 | 96.5% | 17,685 | 98.75% | 17,485 | 98.24% | 17,595 | 98.49% | ||

| Total population | 17,990 | 100% | 18,094 | 100% | 18,015 | 100% | 17,908 | 100% | 17,798 | 100% | 17,865 | 100% | ||

| Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses | ||||||||||||||

Religion

[edit]According to the 2021 census, religious groups in Oak Bay included:[14]

- Irreligion (10,250 persons or 58.1%)

- Christianity (6,430 persons or 36.5%)

- Judaism (260 persons or 1.5%)

- Buddhism (170 persons or 1.0%)

- Sikhism (120 persons or 0.7%)

- Islam (85 persons or 0.5%)

- Hinduism (50 persons or 0.3%)

- Other (280 persons or 1.6%)

Film studio

[edit]During the 1930s, Oak Bay, British Columbia was the original "Hollywood North" where fourteen films were produced in Greater Victoria between 1933 and 1938.[20] In 1932 Kenneth James Bishop leased an off-season exhibition building on the Willows Fairgrounds that was converted to a film sound stage to produce films for the British film quota system under the Cinematograph Films Act 1927[21] and films were produced with Hollywood stars such as Lillian Gish, Paul Muni, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Edith Fellows, Charles Starrett and Rin Tin Tin Jr. Film production was curtailed when the Cinematograph Films Act 1938 specified only British made films would be included in the quota.

The Willows Park Studio films include:

- The Crimson Paradise (1933; "Fighting Playboy" in the US)[22] (The first all talking motion picture in Canada.)[23]

- Secrets of Chinatown (1935; Production Company was Commonwealth Productions Ltd. based on the out of print book The Black Robe by Guy Morton. Kathleen Dunsmuir invested $50,000[clarification needed] in the film. Before completion of the film Commonwealth Productions went bankrupt, Northern Films Ltd. completed post production of the film, Kathleen Dunsmuir lost all $50,000.[23] The film is technically British it received British film registration number br. 11391. The film was seized by the police at request of the Chinese Consul with the claim it was offensive, the film was altered before its release. In Victoria Harry Hewitson the actor playing Chan Tow Ling would remind the audience with the warning it was fictional.[24][25] In addition to Chinatown and surrounding downtown Victoria the Gonzales area is used in outdoor shots of the film.[26][27])

- Fury and the Woman (1936, aka Lucky Corrigan)

- Lucky Fugitives (1936)

- Secret Patrol (1936)

- Stampede (1936)

- Tugboat Princess (1936)

- What Price Vengeance? (1937)

- Manhattan Shakedown (1937)

- Murder is News (1937)

- Woman Against the World (1937)

- Death Goes North (1937)

- Convicted (1938)

- Special Inspector (1938)

- Commandos Strike at Dawn (1942)

Parks

[edit]- Anderson Hill Park - The Vancouver Island Trail's southern terminus is located here

- Uplands Park / Cattle Point (a Garry oak ecosystem).

- Willows Beach

Public safety

[edit]- Oak Bay Emergency Program

- Oak Bay Fire Department - The Oak Bay Fire Department was formed in 1937.[28]

- Oak Bay Police Department - The Oak Bay Police Department was formed in 1906.[29]

- Oak Bay Sea Rescue (OBSR) - Royal Canadian Marine Search and Rescue Station 33 (RCM-SAR) - Oak Bay Sea Rescue was formed in 1977, and is a volunteer organisation. The Unit's Boats are based out of Oak Bay Marina [30]

Education

[edit]Oak Bay is the home of the University of Victoria, a public research institution in the Capital Region District. While much of the University of Victoria campus is located within the District of Oak Bay, parts of it are also located in the adjacent municipality of Saanich.

Oak Bay also hosts a number of academically focused public and private secondary schools which are part of School District 61. There is one public elementary school, Willows Elementary, one public middle school, Monterey Middle School, and one public high school, Oak Bay High School, with the largest student population in the Greater Victoria School District.[31] Residents in the South Oak Bay area may also register their children at the nearby Margaret Jenkins Elementary (in Victoria). In addition to public schools, there are two private schools located in Oak Bay, Glenlyon Norfolk School and St. Michael's University School.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ^ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

References

[edit]- ^ "British Columbia Regional Districts, Municipalities, Corporate Name, Date of Incorporation and Postal Address" (XLS). British Columbia Ministry of Communities, Sport and Cultural Development. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Oak Bay, British Columbia (Code 5917030) Census Profile". 2021 census. Government of Canada - Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2024-10-15.

- ^ "Capital Regional District Victoria BC". CRD. 30 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Doughton, Sandi. "Ancient quake and tsunami in Puget Sound shake researchers". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ "When Victorians Used to Dig Up Indigenous Bones for Fun". The Capital. Retrieved 2020-08-16.

- ^ "Tod House".

- ^ a b Belyk, Robert C. (2011-07-06). Ghosts: True Tales of Eerie Encounters. ISBN 9781926971186.

- ^ Green, Valerie (2001). If These Walls Could Talk: Victoria's Houses from the Past. ISBN 9780920663783.

- ^ Fame, Hockey Hall of. "HHOF | Silverware Trophy Tour". Hockey Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- ^ Woodley, M.; Naish, D.; Shanahan, H. (2008). "How many extant pinniped species remain to be described?". Historical Biology. 20 (4): 225–235. doi:10.1080/08912960902830210. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 14824564.

- ^ "Oak Bay - the Victoria Real Estate Board". www.vreb.org. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals 1991-2020 Data - University of Victoria". Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2024-06-27. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ "Canadian Climate Normals - Climate - Environment and Climate Change Canada". 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2022-10-26). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-11-09.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2021-10-27). "Census Profile, 2016 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2015-11-27). "NHS Profile". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-08-20). "2006 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-07-02). "2001 Community Profiles". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2019-07-02). "Profile of Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 1996 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ "The Oak Bay Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2004-11-21.

- ^ p. 30 Gasher, Mike Hollywood North: The Feature Film Industry in British Columbia UBC Press, 2002

- ^ "The Crimson Paradise". IMDb. 14 December 1933.

- ^ a b Reksten, Terry (December 2009). The Dunsmuir Saga. ISBN 9781926706061.

- ^ "Willows Park Studio, Victoria, British Columbia".

- ^ "Secrets of Chinatown - RBCM Archives".

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Secrets of Chinatown = The Black Robe (1935)". YouTube.

- ^ "Secrets of Chinatown (1931)".

- ^ "Fire Department".

- ^ Van Reeuwyk, Christine (2021-05-29). "Oak Bay cop targets police history, aims to share". www.oakbaynews.com. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ^ "History of OBSR Society / CCGA(P) Unit #33". Oak Bay Sea Rescue Society. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ "School Enrolment Numbers - the Greater Victoria School District No. 61".

- Oak Bay, British Columbia: in Photographs 1906-2006 (book)

- Only in Oak Bay Oak Bay Municipality: 1906-1981 (book)