Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2018) |

Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal, Prince-Archbishop of Vienna | |

| |

| Church | Roman Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Vienna |

| See | St. Stephen's Cathedral |

| Installed | 23 May 1757 |

| Term ended | 14 April 1803 |

| Predecessor | Johann Joseph von Trautson |

| Successor | Sigismund Anton von Hohenwart |

| Other post(s) | Cardinal-Priest of Santi Quattro Coronati (1775–1803)

Titular Archbishop of Cartagine (1751–56) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 7 April 1738 |

| Consecration | 10 October 1751 |

| Created cardinal | 23 November 1761 by Clement XIII |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 October 1714 |

| Died | 14 April 1803 (aged 88) Vienna, Austria, Holy Roman Empire |

| Buried | St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Education | Collegium Germanicum |

| Coat of arms |  |

Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi; (German: Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi von Wall und Sonnenthurm, Italian: Cristoforo Bartolomeo Antonio Migazzi di Waal e Sonnenthurn, Hungarian: Migazzi Kristóf Antal) (20 October 1714, Trento – 14 April 1803, Vienna) was Prince-Archbishop of Vienna.

Early life

[edit]Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi was born in 1714, in the Prince-Bishopric of Trent, part of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire. At nine years of age he entered the school for pages at the residence of Prince-Bishop Lamberg of Passau, who later proposed him for admittance to the Collegium Germanicum in Rome. At the age of twenty-two he returned to the Tyrol to study civil and canon law.

Cardinal Lamberg took him as a companion to the Conclave of 1740, whence Benedict XIV came forth pope; Cardinal Lamberg recommended Migazzi to the new pope. Migazzi remained at Rome, as he stated, "in order to quench my thirst for the best science at its very source". About philosophy he stated about this time:

Without a knowledge of philosophy wit is merely a light fragrance which is soon lost, and erudition a rude formless mass without life or movement, which rolls onward unable to leave any mark of its passage, consuming everything without itself deriving any benefit therefrom.

In 1745, he was appointed auditor of the Rota for the German nation.

Patronage of Maria Theresa

[edit]Owing to the friendship of Benedict XIV, Migazzi concluded several transactions to the satisfaction of the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa, who in return appointed him in 1751 coadjutor to the aged Archbishop of Mechelen. Upon being consecrated bishop, Migazzi was removed to Madrid as ambassador in Spain. After concluding a treaty, in 1756, the Empress appointed him coadjutor of Count Bishop Althan of Waitzen. But as Althan died before Migazzi's arrival, and six months later Prince Archbishop Trantson also died in Vienna, the Empress named Migazzi his successor.

In 1761, Maria Theresa appointed him administrator-for-life of the Bishopric of Vác, and at the same time obtained the cardinal's red for him from Clement XIII. Migazzi was thus in possession of two sees, the revenues of which he applied to their improvement. In Vác (Waitzen), he erected the cathedral and episcopal palace and founded the Collegium pauperum nobilium and a convent. After twenty-five years of his administration, the Concilium locum tenens regium asked him if there was any priest in his diocese in possession of two benefices or offices, as in that case it was Emperor Joseph II's pleasure that one of them should be given up. Migazzi was forced to resign from Vác.

During Maria Theresa's reign in Austria, the so-called Enlightenment era (Aufklärung) developed. "The Masonic lodge of the Three Canons" was printed at Vienna in 1742 and at Prague, in 1749, the "Three Crowned Stars and Honesty". In a memorial to the Empress, written in 1769, the Archbishop designated as the primary causes of current evils the spirit of the times, atheistic literature, the pernicious influence of many professors, the condition of the censorship, contemporary literature, the contempt of the clergy, the bad example of the nobility, the conduct of affairs of state by irreligious persons and neglect of the observance of holy days.

Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus, but Migazzi endeavoured to save it for Austria. He wrote to the Empress:

If the members of the order are dispersed, how can their places be so easily supplied? What expense will be entailed and how many years must pass before the settled condition broken up by the departure of these priests can be restored?

Twenty years later, the Cardinal wrote to Francis I:

Even the French envoy who was last here, did not hesitate, as I can prove to your Majesty, to say that if the Jesuits had not been suppressed, France would not have experienced that Revolution so terrible in its consequences.

Migazzi opposed, as far as they were anticlerical. the government monopoly of educational matters, the "enlightened" theology, the "purified" law, the "enlightenment" literature, "tolerance" and encroachment on purely religious matters. He also founded the "Wiener Priesterseminar", an establishment for the preparation of young priests for parochial work. At Rome, his influence obtained for the Austrian monarch the privilege of being named in the Canon of the Mass. Migazzi lived to see the election of three popes. Maria Theresa and Kaunitz took a lively interest in his accounts of what transpired in the conclave (23 November 1775 – 16 February 1776), which elected Pope Pius VI who subsequently visited Vienna during the reign of Joseph II. That pope owed his election to Migazzi, leader of the Royalist party. The Empress, in a letter to Migazzi sent during the conclave, wrote: "I am as ill-humoured as though I had been three months in conclave. I pray for you; but I am often amused to see you imprisoned."

Rise of Josephinism

[edit]When Frederick II of Prussia heard of the death of the Empress he wrote, "Maria Theresa is no more. A new order of things will now begin."

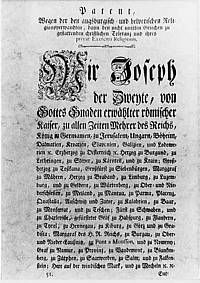

Joseph II, during his ten years' reign, published 6200 laws, court ordinances and decrees affecting the Catholic Church. The first measures, leveled against ecclesiastical jurisdiction, created dissatisfaction as encroachments on the rights of the Church. Cardinal Migazzi sent a number of memorials to Joseph II. Migazzi opposed all the Josephist reform decrees injurious to the Church.

The "simplified and improved studies", the new methods of ecclesiastical education (general seminaries), interference with the constitutions of religious orders, the suppression of convents and violations of their rights and interference with the matrimonial legislation of the Church, called for vigorous protests on the Cardinal's part; but though he protested unceasingly, it was of no avail. After Pius VI's visit to Vienna, the Holy See pronounced no solemn condemnation of Josephinism. On 12 March 1790, Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany, arrived in Vienna, as successor of his brother Joseph, and as early as 21 March, Migazzi presented him with a memorial concerning the sad condition of the Austrian Church. He mentioned thirteen "grievances" and pointed out for each the means of redress: laxity in monastic discipline; the general seminaries; marriage licenses; and the "Religious Commission", which assumed the position of judge of the bishops and their rights. Migazzi expressed his dissatisfaction.

Later years

[edit]Emperor Francis II confirmed the Josephist system throughout his reign. During the French Revolutionary Wars, the "Religious Commission" paid little heed to the representations of the bishops. The Cardinal insisted on its abolition, stating:

I am in all things your Majesty's obedient subject, but in spiritual matters the shepherd must say fearlessly that it is a scandal to all Catholics to see such fetters laid upon the bishops. The scandal is even greater when such power is vested in worldly, questionable, even openly dangerous and disreputable men.

In another matter, he wrote:

The dismal outlook of the Church in your Majesty's dominion is all the more grievous from the fact that one must stand by in idleness, while he realizes how easily the increasing evils could be remedied, how easily your Majesty's conscience could be calmed, the honour of Almighty God, respect for the Faith and the Church of God be secured, the rightful activities of the priesthood set free, and religion and virtue restored to the Catholic people. All this would follow at once, if only your Majesty, setting aside further indecision, would resolve generously and perseveringly to close once for all the sources of so great evil.

The Emperor made concessions, greeted by Migazzi with satisfaction. When the pilgrimage to Maria Zell was once more permitted, the Cardinal in person led the first procession.

Migazzi died in Vienna on 14 April 1803. His body is buried in St. Stephen's Cathedral.

Bibliography

[edit]German

[edit]- Günther Anzenberger: Die Rolle Christoph Graf Migazzis (Erzbischof von Wien 1757–1803) zur Zeit Maria Theresias. Diplomarbeit an der Universität Wien, Wien 1994.

- Peter Hersche (1994), "Migazzi, Christoph Graf", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 17, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 486–488; (full text online)

- Franz Loidl: Geschichte des Erzbistums Wien. Herold, Wien 1983, ISBN 3-7008-0223-4.

- Franz Loidl, Martin Krexner: Wiens Bischöfe und Erzbischöfe. Vierzig Biographien. Schendl, Wien 1983, ISBN 3-85268-080-8.

- Josef Oswald: Migazzi, Christoph Anton Graf v. In: Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche. 2. Auflage, 7. Band. Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 1960.

- Ernst Tomek: Kirchengeschichte Österreichs. Tyrolia, Innsbruck - Wien - München 1935–1959.

- Josef Wodka: Kirche in Österreich. Wegweiser durch ihre Geschichte. Herder, Wien 1959.

- Cölestin Wolfsgruber: Christoph Anton Kardinal Migazzi, Fürsterzbischof von Wien. Eine Monographie und zugleich ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Josphinismus. Hermann Kitz, Ravensburg 1897.

Italian

[edit]- Tani, Maurizio (2003). La committenza artistica del vescovo di Eger, Károly Eszterházy, nell´Ungheria del XVIII secolo, Commentari d'Arte, n. 17-19, pp. 92–107

- Tani, Maurizio (2005). Il ruolo degli Scolopi nel rinnovamento delle arti nell'Europa danubiana del XVIII secolo, in Ricerche, n. 85, pp. 44–55

- Tani, Maurizio (2005). La rinascita culturale del '700 ungherese. Le arti figurative nella grande committenza ecclesiastica. Roma: Pontificia Università Gregoriana. ISBN 88-7839-018-6. edizione on-line

- Tani, Maurizio (2013). Arte, propaganda e costruzione dell'identità nell'Ungheria del XVIII secolo. Il caso della grande committenza di Károly Eszterházy, vescovo di Eger e signore di Pápa in István Monok (a cura di), In Agram adveni. Eger: Líceum Kiadó. ISBN 978-615-5250-26-2. edizione on-line

Hungarian

[edit]- A Váci Egyházmegye Történeti Névtára, Dercsényi Deszõ Vállalata Pestividéki Nyomoda, Vác, 1917

- Bánhidi Láslo, Új Váci Kalauz, Vác 1998

- Sápi Vimos e Ikvai Nándor, Vác Története - Studia Comitatensis voll. 13, 14, 15 - 1983

References

[edit]External links

[edit]- Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi in Austria-Forum (in German) (at AEIOU)

- "Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi von Waal und Sonnenthurn". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney.

- Geschichte der Erzdiözese Wien

- 1714 births

- 1803 deaths

- Burials at St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna

- Archbishops of Vienna

- 18th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the Holy Roman Empire

- 19th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in the Holy Roman Empire

- Conclavists

- Italian Roman Catholic archbishops

- Counts of Austria

- Italian Austro-Hungarians

- People from Trento

- Prince-bishops in the Holy Roman Empire

- Austrian founders

- University and college founders

- Bishops of Vác

- Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum alumni