Socialist Unity Party of Germany

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Socialist Unity Party of Germany Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary | Walter Ulbricht (first) Egon Krenz (last) |

| Founded | 21 April 1946 |

| Dissolved | 16 December 1989 |

| Merger of | East German branches of KPD and SPD |

| Succeeded by | Party of Democratic Socialism |

| Headquarters | Haus am Werderschen Markt, East Berlin |

| Newspaper | Neues Deutschland |

| Youth wing | Free German Youth |

| Pioneer wing | Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation |

| Paramilitary wing | Combat Groups of the Working Class |

| Labour wing | Free German Trade Union Federation |

| Membership (1989) | 2,260,979[1] |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Far-left |

| National affiliation |

|

| Regional affiliation | Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin (1962–1989) |

| International affiliation | Cominform (1947–1956) |

| Colours | Red |

| Anthem | "Lied der Partei" ("Song of the Party") |

| West German affiliation |

|

| Party flag | |

| |

|

|---|

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (German: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, pronounced [zotsi̯aˈlɪstɪʃə ˈʔaɪnhaɪtspaʁˌtaɪ ˈdɔʏtʃlants] ; SED, pronounced [ˌɛsʔeːˈdeː] )[3] was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from the country's foundation in 1949 until its dissolution after the Peaceful Revolution in 1989. It was a Marxist–Leninist communist party,[4] established in 1946 as a merger of the East German branches of the Communist Party of Germany and Social Democratic Party of Germany.

The GDR was effectively a one-party state.[5] Other institutional popular front parties were permitted to exist in alliance with the SED; these parties included the Christian Democratic Union, the Liberal Democratic Party, the Democratic Farmers' Party, and the National Democratic Party. These parties were largely subservient to the SED, and had to accept the SED's "leading role" as a condition of their existence. Long one of the most rigidly Stalinist parties in the Soviet bloc, the SED rejected the liberalisation policies of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, such as perestroika and glasnost in the 1980s, which would lead to the GDR's isolation from the restructuring USSR and the party's downfall in the autumn of 1989.

The SED was officially organized on the basis of democratic centralism. Theoretically, the highest body of the SED was the Party Congress, convened every fifth year. When the Party Congress was not in session, the Central Committee was the highest body, but since the body normally met only once a year most duties and responsibilities were vested in the Politburo and its Standing Committee. Members of the latter were the top leadership of both the party and the state, with the party's general secretary effectively having the authority of a dictator. From 1960, many of them concurrently served on the State Council of East Germany, replacing the President of the German Democratic Republic.

Ideologically, the party, from its foundation, adhered to Marxism–Leninism, and pursued state socialism, under which all industries in East Germany were nationalized, and a command economy was implemented. The SED made the teaching of Marxism–Leninism and the Russian language compulsory in schools.[6] Walter Ulbricht was the party's dominant figure and effective leader of East Germany from 1950 to 1971. In 1953, an uprising against the Party was met with violent suppression by the Ministry of State Security and the Soviet Army. In 1971, Ulbricht was succeeded by Erich Honecker who presided over a stable period in the development of the GDR until he was forced to step down during the 1989 revolution. The party's last leader, Egon Krenz, was unsuccessful in his attempt to retain the SED's hold on political governance of the GDR and was imprisoned after German reunification.

The SED's long-suppressed reform wing took over the party in the autumn of 1989. In hopes of changing its image, it reorganized as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), abandoning Marxism–Leninism and declaring itself a democratic socialist party. It received 16.4% of the vote in the 1990 parliamentary elections. In 2007, the PDS merged with Labour and Social Justice (WASG) into The Left (Die Linke), the sixth largest party in the German Parliament following the 2021 federal election.

Early history

[edit]

The SED was founded on 21 April 1946 by a merger of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) which was based in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany and the Soviet-occupied sector of Berlin. Official East German and Soviet histories portrayed this merger as a voluntary pooling of efforts by the socialist parties.[7] However, there is much evidence that the merger was more troubled than commonly portrayed. By all accounts, the Soviet occupation authorities applied great pressure on the SPD's eastern branch to merge with the KPD. The newly merged party, with the help of the Soviet authorities, swept to victory in the 1946 elections for local and regional assemblies held in the Soviet zone. However, these elections were held under less-than-secret conditions, thus setting the tone for the next four decades. Conversely, in the Berlin City Council elections held that same year, the merger fared more poorly. In that contest, the SED received less than half the votes of the SPD. The bulk of the Berlin SPD remained aloof from the merger, even though Berlin was deep inside the Soviet zone.

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (Russian initials: SVAG) directly governed the eastern areas of Germany following World War II, and their intelligence operations carefully monitored all political activities. An early intelligence report from SVAG Propaganda Administration director Lieutenant Colonel Sergei Ivanovich Tiulpanov indicates that the former KPD and SPD members created different factions within the SED and remained mutually quite antagonistic for some time after the formation of the new party. The report also noted considerable difficulty in convincing the masses that the SED was an authentic German political party and not merely a tool of the Soviet occupation force.

According to Tiulpanov, many former members of the KPD expressed the sentiment that they had "forfeited [their] revolutionary positions, that [the KPD] alone would have succeeded much better had there been no SED, and that the Social Democrats are not to be trusted" (Tiulpanov, 1946). Tiulpanov also indicated that there was a marked "political passivity" among former SPD members, who felt they were being treated unfairly and as second-class party members by the new SED administration. As a result, the early SED party apparatus frequently became effectively immobilised as former KPD members began discussing any proposal, however small, at great length with former SPD members, so as to achieve consensus and avoid offending them. Soviet intelligence claimed to have a list of names of an SPD group within the SED that was covertly forging links with the SPD in the West and even with the Western Allied occupation authorities.

A problem for the Soviets that they identified with the early SED was its potential to develop into a nationalist party. At large party meetings, members applauded speakers who talked of nationalism much more than when they spoke of solving social problems and gender equality. Some even proposed the idea of establishing an independent German socialist state free of both Soviet and Western influence, and of soon regaining the formerly German land that the Yalta Conference, and ultimately the Potsdam Conference, had (re)allocated to Poland, the USSR, and Czechoslovakia. The SED began to integrate former members of the Nazi Party at its founding. However, the strategy was controversial within the party. The SED therefore set up the National Democratic Party of Germany (NDPD) in 1948 as satellite party that could serve as a pool for former Nazis and Wehrmacht officers. Nonetheless, the SED continued to absorb former Nazi Party members. By 1954, 27 percent of all members of the SED and 32.2 percent of all public service employees were former members of the Nazi Party.[8]

Soviet negotiators reported that SED politicians frequently went beyond the boundaries of the political statements which had been approved by the Soviet monitors, and there was some initial difficulty making regional SED officials realize that they should think carefully before opposing the political positions decided upon by the Central Committee in Berlin.

A monopoly of power

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Although it was nominally a merger of equals, from the beginning the SED was dominated by Communists. By the late 1940s, the SED began to purge most recalcitrant Social Democrats from its ranks. By the time of East Germany's formal establishment in 1949, the SED was a full-fledged Communist party—essentially the KPD under a new name. It began to develop along lines similar to other Communist parties in the Soviet bloc.

Although other parties nominally continued to exist, the Soviet occupation authorities forced them to join in the National Front of Democratic Germany, a nominal coalition of parties that was for all intents and purposes controlled by the SED. By ensuring that Communists predominated on the list of candidates put forward by the National Front, the SED effectively predetermined the composition of legislative bodies in the Soviet zone, and from 1949 in East Germany.

Over the years, the SED gained a reputation as one of the most hardline parties in the Soviet bloc. When Mikhail Gorbachev initiated reforms in the Soviet Union in the 1980s, the SED held to an orthodox line.

Organisation

[edit]Basic organisation

[edit]The party organisation was based on, and co-located with, the institutions of the German Democratic Republic. Its influence stood behind and shaped every facet of public life. The party required every member to live by the mantra "Where there is a comrade, the party is there too" (Wo ein Genosse ist, da ist die Partei).[9] This meant that the party organisation was at work in publicly owned industrial and quasi-commercial enterprises, machine and tractor stations, publicly owned farms and in the larger agricultural cooperatives, expressly mandated to monitor and regulate the operational management of each institution.

The smallest organisational unit in the party was the Party Group. Group members elected one of their number Party Group Organiser (PGO), to take responsibility for Party Work. There were also a Treasurer, an Agitator, and according to the size of the group other associated members included in the Party Group leadership. Where there were several Party Groups operating in a single place they would be combined in a Departmental Party Organisation (APO / Abteilungsparteiorganisation) which in turn would have its own leadership and an APO Party Secretariat.

Party conference

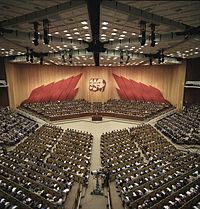

[edit]The Party conference was formally the party's leading institution.

Increasingly, party conferences were planned with military-level precision. Their choreography was carefully undertaken to ensure that they were understood as high-profile society events. They were very much more than mere political functions. Delegates were selected from the regional and sectional party organisations according to criteria determined by the Party Central Committee. Care was taken over the proportions of women, of youth representatives, of members from approved Mass organisations and of "exemplary" workers.

Party Secretaries

[edit]Party secretaries existed at different levels within the party. They usually held their offices on an unsalaried basis, often combining their party secretarial duties with a salaried function. Where a basic administrative unit grew beyond certain size tension tended to arise between the party secretary and fellow committee members, and at this point a full-time salaried party secretary would be appointed. Party secretaries in very large industrial combines and other economically important institutions would combine their party secretarial roles with membership of a more powerful body, applying a structural element maintained right up to the level of the Party Central Committee. The task of the Party Secretaries was the organisation of political work. They prepared the party meetings and organised political training in partnership with the party leaderships. They ensured implementation of and compliance with party decisions and undertook general reporting and leadership duties. They were also required to provide a monthly report on "Morale and Opinions" ("Stimmungen und Meinungen") concerning the people covered by their party secretarial duties.

Where work on occasion attracted criticism, there were many ways on which changes could be passed on. This fact lay behind the burgeoning bureaucratization of the party apparatus and the presence of Stalinistic tendencies. Party secretaries underwent a special monthly political process that included instructive guidance and verification by representatives from higher level party committees. Along with their party responsibilities, party secretaries were members of the state administration, and they secured the leadership role that the SED claimed for itself in businesses and offices. Managerial decisions were discussed and ultimately decided in party committees. This meant that a manager, provided he was a party member, was committed to implementing those decisions.

Sectional directorates

[edit]The basic organisional unit in an organisation or department was placed under the control of the party's sectional leadership team ("SED-Kreisleitung"). There were in total 262 of these sectional leadership teams, including one each for the Free German Youth (FDJ), the Trade Union Federation (FDGB), the Foreign Ministry, the Foreign Trade Ministry, the State Railway organisation, the military branches of the Interior Ministry, the Ministry for State Security (Stasi), the National People's Army, each of which had its own integrated political-administrative structure.

Regional directorates

[edit]The party's regional structure started with the country's fifteen regions. Regional level government structure changed dramatically with the abolition of regional assemblies in 1952, but each administrative structure always had a party secretary, applying a structure also replicated in administrative structures at local levels.

The regional party leadership team ("SED Bezirksleitung"/ BL) was an elected body analogous to the Central Committee, membership of which was unpaid. It worked alongside the administrative body of paid officials who were occasionally also members of the party leadership team.

At a regional level the SED leadership team was headed by a Secretariat. The Secretariats always had a First Secretary (also responsible for Security Affairs) and a Second Secretary (also responsible for Cadre Affairs), and secretaries responsible for "Agitation and propaganda", Economy, Science, Culture and Agriculture. There were also regional teams to shadow the regional teams of national institutions such as the FDJ, the FDGB and the Planning Commission. The First Secretaries of the regional FDJ and chairmen of the regional FDGB and Planning Commission were always Secretariat members too.

First Secretaries of regional party organisations held significant power in their respective regions, with some First Secretaries such as Hans-Joachim Böhme or Hans Albrecht being described as despotic, sometimes dictatorial. First Secretaries were always full members of the Central Committee and sometimes even candidate or full members (always the First Secretary in East Berlin) of the Politburo. First Secretaries of Bezirke that had a significant border with West Germany usually also served on the National Defence Council.

| Bezirk | First Secretary | incumbent since | note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bezirk Rostock | Ernst Timm | 29 April 1975 | |

| Bezirk Neubrandenburg | Johannes Chemnitzer | 16 February 1963 | |

| Bezirk Schwerin | Heinz Ziegner | 28 January 1974 | |

| Bezirk Potsdam | Günther Jahn | 23 January 1976 | |

| Bezirk Frankfurt (Oder) | Christa Zellmer | 3 November 1988 | |

| Bezirk Cottbus | Werner Walde | 1 June 1969 | Politburo candidate member |

| Bezirk Magdeburg | Werner Eberlein | 15 June 1983 | Politburo member

National Defence Council member |

| Bezirk Halle | Hans-Joachim Böhme | 5 May 1981 | Politburo member |

| Bezirk Leipzig | Horst Schumann | 21 November 1970 | |

| Bezirk Dresden | Hans Modrow | 3 October 1973 | |

| Bezirk Karl-Marx-Stadt | Siegfried Lorenz | March 1976 | Politburo member |

| Bezirk Erfurt | Gerhard Müller | 11 April 1980 | Politburo candidate member |

| Bezirk Gera | Herbert Ziegenhahn | 14 February 1963 | |

| Bezirk Suhl | Hans Albrecht | 15 August 1968 | National Defence Council member |

| East Berlin[a] | Günter Schabowski | 22 November 1985 | Politburo member |

| Wismut[b] | Alfred Rohde | 5 February 1971 |

Central Committee

[edit]When the Party Congress was not in session, the Central Committee was the party's leading element. Power was centred on the Committee Secretariat, which was chaired by a General Secretary, named First Secretary from 1953 to 1976. This function was combined with chairmanship of the Politburo. The General Secretary until 1971 was Walter Ulbricht: he was deposed by Erich Honecker, who in turn was deposed by Egon Krenz. Unlike in the Soviet Union, the SED only had "Second Secretaries" on the local and regional levels, but not in the Central Committee. That being said, some Politburo members and secretaries held an unofficial number two spot, most notably Karl Schirdewan and then Honecker during the tenure of Walter Ulbricht and Paul Verner, then Egon Krenz during the tenure of Honecker.

In the political hierarchy of the GDR, members of the Central Committee ranked above government ministers.

In July 1950, at the third Party Conference, the SED's Central Committee was elected on the Soviet model, which at this time employed a single list electoral system: most members of the serving party executive were replaced. It was striking that more than 62% of the new Central Committee members had been members of the Communist Party (KPD) before the party merger of 1946. Four years on, there was little sign of the KPD/SPD parity that had been invoked when the SED was created.[10]

By 1989, membership of the Central Committee had increased to 165: there were also 57 people listed as candidates for membership. All the high ranking party functionaries were represented in it along with other senior government officials (provided they were already party members). Beyond the professional functionaries and politicians the Committee also included the chiefs of the country's leading institutions and industrial combines, the president of the country's Writers' Association, top military officers and party veterans.

The Party Central Committee, reflecting the country's overall power structure, was overwhelmingly male: the proportion of women never rose above 15%.

Central Party Control Commission

[edit]The Central Party Control Commission (ZPKK) was the supreme disciplinary body of the SED operating under and elected by the SED Central Committee. Its role was enforcing conformity and eliminating perceived opposition within the party ranks, closely working with the Stasi and Volkspolizei. It had corresponding bodies at all levels of the party in the form of Bezirk (BPKK) and district Party Control Commissions (KPKK). Notable ZPKK victims include Robert Havemann and Rudolf Herrnstadt.

There also existed a Central Auditing Commission (ZRK) to inspect the party finances analogous to the CPSU Central Auditing Commission, though due to its limited jurisdiction, its practical significance was minor compared to the ZPKK.

Politburo of the Central Committee

[edit]The most important day-to-day work of the Central Committee was undertaken by the Politburo, a small circle of senior party officers, comprising between 15 and 25 full members, along with approximately 10 candidate (non-voting) members. The politburo members included approximately ten Central Committee Secretaries. The General Secretary of the Central Committee also held the Chairmanship of the Politburo (along with all his other functions). The country's government, formally headed by the Council of Ministers, served largely to implement the Politburo's decisions. This meant that while the Council of Ministers was nominally the highest executive authority in the GDR, in reality it was under the permanent control of the Party Committees, a structure that ensured the "leading role" of the SED. This status was spelled out expressly after the constitutional changes introduced in 1968, which defined East Germany as a "socialist state" led by "the working class and its Marxist–Leninist party." The Chairman of the Council of Ministers and the president of the National legislature ("Volkskammer") were also members of the Politburo.

The meetings of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the SED usually took place every Tuesday in the conference room on the 2nd floor of the Central Committee building on Werderscher Markt, starting at 10 a.m. The meetings usually lasted only 2 hours and included up to 10 to 20 items on the agenda. According to former Politburo members Egon Krenz and Günter Schabowski, most Politburo members had little to say, much less dissent.

Secretariat of the Central Committee

[edit]The Central Committee Secretariat met each Wednesday to implement decisions finalised by the Politburo the previous day and to prepare the agenda for the Central Committee's next weekly meeting. The Secretariat comprised the Central Committee Party Secretaries. The Secretariat played a decisive role in selecting the Nomenklatura of the Central Committee. Nomenklatura members were the holders of the top 300 or so positions in the party and the state: changes to the Nomenklatura membership list required the approval of the Central Committee Secretariat.

The Secretariat was the connecting element between the Politburo and the Central Committee Departments. These departments, whose heads were always full members of the Central Committee, formulated policy for the party and thus the country, with most departments mirroring ministries of the GDR (for example, there was a Ministry of Light Industry and a Ministry of District-led and foodstuffs industry). Department could de facto issue binding orders to the respective ministries, though de jure this was only possible for the secretaries. A notable exception was the Ministry of People's Education, which was not under supervision of the People's Education Department, but directly under the General Secretary, as Minister Margot Honecker was the General Secretary's wife. Secretaries were usually assigned to multiple departments, for example, throughout the GDR's existence, there was one Economy Secretary.

The party newspaper Neues Deutschland was organised as a department, its Editor-in-chief having department head rank. Similarly, the Party Academy and the Institute for Marxism–Leninism were organised as departments, their directors having department head rank.

| Department | Head | Responsible Secretary |

|---|---|---|

| Agitation[c] | Heinz Geggel | Joachim Herrmann |

| Propaganda[d] | Klaus Gäbler | |

| Friendly Parties | Karl Vogel | |

| Neues Deutschland | Herbert Naumann[e] | |

| Foreign Information | Manfred Feist | Hermann Axen |

| International Relations | Günter Sieber | |

| International Politics and Economics[f] | Gunter Rettner | |

| Youth | Gerd Schulz | Egon Krenz |

| Sport | Rudolf Hellmann | |

| Security Affairs | Wolfgang Herger | |

| State and Legal Affairs | Klaus Sorgenicht | |

| Cadre Affairs | Fritz Müller | Erich Honecker |

| Verkehr[g] | Julius Cebulla | |

| Party Organs | Heinz Mirtschin | Horst Dohlus |

| Woman | Ingeburg Lange[h] | |

| Science | Johannes Hörnig | Kurt Hager |

| Education | Lothar Oppermann | |

| Culture | Ursula Ragwitz | |

| Health Policy | Karl Seidel | |

| "Karl Marx" Party Academy | Kurt Tiedke[i] | |

| Institute for Marxism–Leninism | Günter Heyden[j] | |

| Agriculture | Helmut Semmelmann | Werner Krolikowski |

| Trade and Supply | Hilmar Weiß | Werner Jarowinsky |

| Church Affairs | Peter Kraußer | |

| Planning and Finances | Günter Ehrensperger | Günter Mittag |

| Research and Technical Development | Hermann Pöschel | |

| Trade Unions and Social Policy | Fritz Brock | |

| Construction | Gerhard Trölitzsch | |

| Mechanical Engineering and Metallurgy | Klaus Blessing | |

| Basic Industries | Horst Wambutt | |

| Railways, Transportation and Communications | Dieter Wöstenfeld | |

| Light, Food and Bezirk-managed Industries | Manfred Voigt | |

| Socialist Economic Management | Carl-Heinz Janson | |

| Financial Administration and Party Businesses | Heinz Wildenhain | Edwin Schwertner[k] |

| Management of Commercial Enterprises | Günter Glende | |

Party Congresses

[edit]The 1st Congress

[edit]The 1st Party Congress (Vereinigungsparteitag), which convened on 21 April 1946, was the unification congress. This congress elected two co-chairmen to lead the party: Wilhelm Pieck, former leader of the eastern KPD, and Otto Grotewohl, former leader of the eastern SPD. The union was initially intended to apply to the whole of occupied Germany. The union was rejected consistently in the three western occupation zones, where both parties remained independent. The union of the two parties was thus effective only in the Soviet zone. The SED was modeled after the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The 2nd Congress

[edit]The 2nd Party Congress convened from 20 to 24 July 1947. It adopted a fresh party statute and transformed the party executive committee into a central committee (Zentralkomitee or ZK).

The 3rd Congress

[edit]The 3rd Party Congress convened in July 1950 and emphasized industrial progress. The industrial sector, employing 40% of the working population, was subjected to further nationalization, which resulted in the formation of "people's enterprises" (German: Volkseigener Betrieb, VEB). These enterprises incorporated 75% of the industrial sector. At the same time, the party completed its transformation into a more orthodox Soviet-style party with the election of Walter Ulbricht as the party's general secretary.

The 4th Congress

[edit]The 5th Congress

[edit]The 6th Congress

[edit]The 6th Party Congress convened from 15 to 21 January 1963. The congress approved a new party program and a new party membership statute. Walter Ulbricht was re-elected as the party's First Secretary. A new economic policy was introduced, more strongly centralized – the "New Economic System".

The 7th Congress

[edit]First Secretary Walter Ulbricht announced the "ten requirements of the socialist moral and ethics". During his report at the 7th Party Congress in 1967, Erich Honecker had called for a return to an orthodox Socialist economic system, away from the recently instituted New Economic System. But the about-face in economic policy that year cannot be attributed to Honecker's advancement alone. During the previous two winters, the GDR had been plagued with power shortages and traffic breakdowns.

The 8th Congress

[edit]From 1971 onwards, congresses were held every five years. The last was the 11th Party Congress in April 1986. In theory, the party congresses set policy and elected the leadership, provided a forum for discussing the leadership's policies, and undertook activities that served to legitimize the party as a mass movement. They were formally empowered to pass both the party program and the statutes, to establish the general party line, to elect the members of the Central Committee and the members of the Central Auditing Commission, and to approve the Central Committee's report. Between congresses the Central Committee could convene a party conference to resolve policy and personnel issues.

In the spring of 1971, the 8th Congress rolled back some of the programs associated with the Ulbricht era and emphasized short-term social and economic problems. The SED used the occasion to announce its willingness to cooperate with West Germany and the Soviet Union in helping to solve a variety of international problems, particularly the future political status of Berlin. Another major development initiated at the congress was a strengthening of the Council of Ministers at the expense of the Council of State; this shift subsequently played an important role in administering the "Main Task" program. The SED further proclaimed that greater emphasis would be devoted to the development of a "socialist national culture" in which the role of artists and writers would be increasingly important. Honecker was more specific about the SED's position toward the intelligentsia at the Fourth Plenum of the Central Committee, where he stated: "As long as one proceeds from the firm position of socialism, there can in my opinion be no taboos in the field of art and literature. This applies to questions of content as well as of style, in short to those questions which constitute what one calls artistic mastery."

The 9th Congress

[edit]

The 9th Party Congress in May 1976 can be viewed as a midpoint in the development of SED policy and programs. Most of the social and economic goals announced at the 7th Congress had been reached; however, the absence of a definitive statement on further efforts to improve the working and living conditions of the population proved to be a source of concern. The SED sought to redress these issues by announcing, along with the Council of Ministers and the leadership of the FDGB, a specific program to raise living standards. The 9th Congress initiated a hard line in the cultural sphere, which contrasted with the policy of openness and tolerance enunciated at the previous congress. Six months after the 9th Congress, for example, the GDR government withdrew permission for the singer Wolf Biermann to live in East Germany. The congress also highlighted the fact that East Germany had achieved international recognition in the intervening years. East Germany's growing involvement in both the East European economic system and the global economy reflected its new international status. This international status and the country's improved diplomatic and political standing were the major areas stressed by this congress. The 9th Party Congress also served as a forum for examining the future challenges facing the party in domestic and foreign policy. On the foreign policy front, the major events were various speeches delivered by representatives of West European Marxist–Leninist parties, particularly the Italian, Spanish, and French, all of which expressed in varying ways ideological differences with the Soviet Union. At the same time, although allowing different views to be heard, the SED rejected many of these criticisms in light of its effort to maintain the special relationship with the Soviet Union emphasized by Honecker. Another major point of emphasis at the congress was the issue of inter-German détente. On the East German side, the benefits were mixed. The GDR regime considered economic benefits as a major advantage, but the party viewed with misgivings the rapid increase in travel by West Germans to and through the GDR. Additional problems growing out of the expanding relationship with West Germany included conflict between Bonn and East Berlin on the rights and privileges of West German news correspondents in East Germany; the social unrest generated by the "two-currency" system, in which East German citizens who possessed West German D-marks were given the privilege of purchasing scarce luxury goods at special currency stores (Intershops); and the ongoing arguments over the issue of separate citizenship for the two German states, which the SED proclaimed but which the West German government refused to recognize as late as 1987.

During the 9th Congress, the SED also responded to some of the public excitement and unrest that had emerged in the aftermath of the signing of the Helsinki Accords, the human rights documents issued at the meetings in 1975 of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Before the congress was convened, the SED had conducted a "People's Discussion" in order openly to air public concerns related to East Germany's responsibility in honoring the final document of the Helsinki conference.

The 10th Congress

[edit]The 10th Congress, which took place in April 1981, celebrated the status quo; the meeting unanimously re-elected Honecker to the office of general secretary, and there were no electoral surprises, as all incumbents except the ailing 76-year-old Albert Norden were returned to the Politbüro and the Secretariat. The congress highlighted the importance of policies that had been introduced or stressed at the two previous congresses and that had dominated East German life during the 1970s. As in the past, Honecker stressed the importance of the ties to the Soviet Union. In his closing remarks, he stated: "Our party, the SED, is linked forever with the party of Lenin, [the CPSU]." A delegation led by chief party ideologue Mikhail Suslov, a member of the CPSU Politburo, represented the CPSU at the SED congress. Honecker reiterated earlier positions on the relationship between the two German states, stressing that they were two sovereign states that had developed along different lines since World War II, and that their differences had to be respected by both sides as they continued efforts toward peaceful coexistence despite membership in antagonistic alliances. In his speeches, Honecker, along with other SED officials, devoted greater attention to Third World countries than he had done in the past. Honecker mentioned the continually increasing numbers of young people from African, Asian, and Latin American countries who received their higher education in East Germany, and he referred to many thousands of people in those countries who had been trained as apprentices, skilled workers, and instructors by teams from East Germany.

The bulk of the Central Committee report delivered at the opening session of the congress by the general secretary discussed the economic and social progress made during the five years since the 9th Congress. Honecker detailed the increased agricultural and industrial production of the period and the resultant social progress as, in his words, the country continued "on the path to socialism and communism." Honecker called for even greater productivity in the next five years, and he sought to spur individual initiative and productivity by recommending a labor policy that would reward the most meritorious and productive members of society.

The 11th Congress

[edit]

The 11th Congress, held 17–21 April 1986, unequivocally endorsed the SED and Honecker, whom it confirmed for another term as party head. The SED celebrated its achievements as the "most successful party on German soil", praised East Germany as a "politically stable and economically efficient socialist state", and declared its intention to maintain its present policy course. East Germany's successes, presented as a personal triumph for Honecker, marked a crowning point in his political career. Mikhail Gorbachev's presence at the congress endorsed Honecker's policy course, which was also strengthened by some reshuffling of the party leadership. Overall, the 11th Congress exhibited confidence in East Germany's role as the strongest economy and the most stable country in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev praised the East German experience as proof that central planning could be effective and workable in the 1980s.

Official statements on the subject of foreign policy were mixed, particularly with respect to East Germany's relations with West Germany and the rest of Western Europe. Honecker's defense of his policy of "constructive dialogue" appeared in tune with Gorbachev's own calls for disarmament and détente in Europe. However, the SED leadership made it unequivocally clear that its foreign policy, including relations with West Germany, would remain closely coordinated with Moscow's. Although Honecker's criticism of West Germany was low key, Gorbachev's was sharp, attacking Bonn's participation in the United States Strategic Defense Initiative and the alleged "revanchism" in West Germany. However, after a final round of talks with Gorbachev, Honecker signed a hard-line communiqué that openly attacked the policies of the West German government. Overall, Gorbachev's statements suggested that the foreign policy emphasis would be on a common foreign policy adhered to by all members of the Warsaw Pact under Soviet direction. Until the 11th Party Congress, East German leaders had maintained that small and medium states had a significant role to play in international affairs. As a result of Soviet pressure, such statements disappeared from East German commentary on foreign policy.

Final days: collapse of the SED

[edit]

On the day of the 40th anniversary of the founding of the GDR, 7 October 1989, the old Social Democratic Party was illegally refounded. The rest of October saw widespread protests across the country, including in East Berlin and Leipzig. At a special Politbüro meeting on 18 October, Honecker was voted out as general secretary and replaced by Egon Krenz, the party's number-two leader. Krenz tried to portray himself as a reformer, but few believed him. He was almost as detested as Honecker himself, and most of the populace remembered that only four months earlier, he had gone to China to thank the regime there for the suppression in Tiananmen Square.[11] Krenz made some attempts to adjust state policy. However, he could not (or would not) satisfy the growing demands of the people for increased freedom.

One of the regime's efforts to stem the tide ended up being its death knell. On 9 November the SED Politbüro drafted new travel regulations allowing anyone who wanted to visit West Germany to do so by crossing East Germany's borders with official permission. However, no one told the party's unofficial spokesman, East Berlin party boss Günter Schabowski, that the regulations were to take effect the next afternoon. When a reporter asked him when the regulations were to be in place, Schabowski assumed they were already in effect and replied, "As far as I know—effective immediately, without delay." This was widely interpreted as a decision to open the Berlin Wall. Thousands of East Berliners crowded at the Wall, demanding to be let through. Unprepared and unwilling to use force, the guards were quickly overwhelmed and let them through the gates to West Berlin.

The fall of the Wall destroyed the SED politically. On 1 December 1989, the GDR parliament (Volkskammer) rescinded the clause in the GDR Constitution which defined the country as a socialist state under the leadership of the SED, thus formally ending Communist rule in East Germany. On 3 December 1989, the entire Central Committee and Politbüro—including Krenz—resigned.

Rebirth as the PDS

[edit]Some younger members of the SED had been receptive to Gorbachev's reforms, but had more or less been silenced until the events of 1989. Soon after the SED abandoned power, Gregor Gysi, a reformist, was elected to the new post of party chairman. In his first speech, Gysi admitted that the SED was responsible for the country's economic problems—thus repudiating everything the party had done since 1949. He also declared that the party needed to adopt a new form of socialism.[12] As December wore on, most of the party's hardliners—including Honecker, Krenz and others—were pushed out as the party made a desperate attempt to change its image. By the time of a special 16 December congress, the SED was no longer a Marxist–Leninist party. To distance itself from its repressive past, the party added "Party of Democratic Socialism" (PDS) to its name. On 4 February 1990, what remained of the party was renamed solely as the PDS. On 18 March 1990, the PDS was roundly defeated in the first—and as it turned out, only—free election in the GDR; the Alliance for Germany coalition, led by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), won on a platform of speedy reunification with the West.

The SED had sequestered money overseas in secret accounts, including some which turned up in Liechtenstein in 2008. This was returned to the German government, as the PDS had rejected claims to overseas SED assets in 1990.[13] The vast majority of domestic SED assets were transferred to the GDR government before unification. Legal issues over back taxes possibly owed by the PDS on former SED assets were eventually settled in 1995, when an agreement between the PDS and the Independent Commission on Property of Political Parties and Mass Organizations of the GDR was confirmed by the Berlin Administrative Court.[14]

The PDS survived the reunification of Germany. It was represented in the Bundestag without interruption until 2007, and eventually began growing again. It has remained influential in former eastern Germany, especially at the state and local levels. It has been important in addressing East-German issues and addressing social problems. In 2007 the PDS merged with the western-based Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative (WASG) to create the new party The Left (Die Linke), which has resulted in a higher acceptance in western states, the party now also being represented in the parliaments of Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony, Bremen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, Hesse and Hamburg.

West Berlin branch

[edit]Initially the SED had a branch in West Berlin, but in 1962 that branch became a separate party called the Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Westberlins – SEW). The party changed its name to Socialist Initiative (Sozialistische Initiative) in April 1990, then dissolved in June 1991, part of its members subsequently joining the Party of Democratic Socialism.

General Secretaries of the Central Committee of the SED

[edit]| # | Picture | Name | Took office | Left office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Chairmen of the Socialist Unity Party Vorsitzende der Sozialistischen Einheitspartei Deutschlands | |||||

|

Wilhelm Pieck (1876–1960) |

22 April 1946 | 25 July 1950 | ||

|

Otto Grotewohl (1894–1964) | ||||

| General Secretary of the Central Committee (titled as First Secretary of the Central Committee 1953–1976) Generalsekretär/Erster Sekretär des Zentralkommitees | |||||

| 1 |  |

Walter Ulbricht (1893–1973) |

25 July 1950 | 3 May 1971 | |

| 2 |  |

Erich Honecker (1912–1994) |

3 May 1971 | 18 October 1989 | |

| 3 |  |

Egon Krenz (1937–) |

18 October 1989 | 3 December 1989 | |

| (Honorary) Chairman of the Central Committee Vorsitzender des Zentralkommitees | |||||

|

Walter Ulbricht (1893–1973) |

3 May 1971 | 1 August 1973 | ||

Electoral history

[edit]GDR Volkskammer elections

[edit]| Election | Party leader | Vote | % | Seats | +/– | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Wilhelm Pieck Otto Grotewohl |

as part of Democratic Bloc | 450 / 1,525 [l]

|

– | ||

| 1950 | Walter Ulbricht | as part of National Front | 110 / 400

|

|||

| 1954 | 117 / 400

|

|||||

| 1958 | 117 / 400

|

|||||

| 1963 | 110 / 434

|

|||||

| 1967 | 110 / 434

|

|||||

| 1971 | 110 / 434

|

|||||

| 1976 | Erich Honecker | 110 / 434

|

||||

| 1981 | 127 / 500

|

|||||

| 1986 | 127 / 500

|

|||||

There were effective constitutional structures in place to ensure that the ruling SED was able to control the Volkskammer because of the extent to which it controlled other parties and mass organisations which also received predetermined fixed quotas of Volkskammer seats.

- ^ East Berlin was not officially counted as a Bezirk, but the East Berlin party organisation was still a Bezirksleitung

- ^ The party organisation at Wismut was called Gebietsparteileitung (English: Territorial Party Organization) and had the rank of a Bezirksleitung. This contrasted with the party organisations at almost all other large industrial enterprises, who only held Kreisleitung rank.)

- ^ Agitation and Propaganda until 1963

- ^ Agitation and Propaganda until 1963

- ^ Editor-in-chief with department head rank

- ^ West Department until 1984

- ^ Conspiratorial department, responsible for courier services, funding for the German Communist Party etc.

- ^ department head since 1961, responsible Central Committee Secretary since 1973

- ^ School principal with department head rank

- ^ Institute director with department head rank

- ^ as head of the Politburo's Office

- ^ The 1,400 elected members of the Third German People's Congress selected the members of the second German People's Council.

Allied occupation of Germany (1946)

[edit]| Election | Votes | Seats | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946, Soviet occupation zone | 4,685,304 | 47.57% (No. 1) | 249 / 519

| ||

| 1946, Berlin | 412,582 | 19.8% (No. 3) | 26 / 130

| ||

See also

[edit]- The Left

- Volkskammer

- Politics of Germany

- List of political parties in Germany

- List of foreign delegations at the 9th SED Congress

- Free German Youth

- Eastern Bloc politics

References

[edit]- ^ Dirk Jurich, Staatssozialismus und gesellschaftliche Differenzierung: eine empirische Studie, p.31. LIT Verlag Münster, 2006, ISBN 3825898938

- ^ Gabriel Berger: Mir langt’s, ich gehe. Der Lebensweg eines DDR-Atomphysikers von Anpassung zu Aufruhr. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1988, ISBN 3-451-08408-2, S. 42.

- ^ Orlow, Dietrich (29 October 2015). Socialist Reformers and the Collapse of the German Democratic Republic. Springer. ISBN 9781137574169.

- ^ Political Systems of the World. Allied Publishers. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-81-7023-307-7.

- ^ Frank B. Tipton (2003). "East Germany: The structure and functioning of a one-party state". A History of Modern Germany Since 1815. A&C Black. pp. 545–548. ISBN 978-0-8264-4909-2.

- ^ Grix, Jonathan; Cooke, Paul (2003). East German Distinctiveness in a Unified Germany. A&C Black. p. 17. ISBN 1902459172.

- ^ On the discussion about Social Democrats joining the SED see Steffen Kachel, Entscheidung für die SED 1946 – ein Verrat an sozialdemokratischen Idealen?, in: Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, No. I/2004.

- ^ Pötzl, Norbert F. (26 May 2015). "Karrieren ehemaliger Nazis in der DDR: Erst braun, dann rot". Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg: Der Spiegel GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

Aber auch die SED sog weiter ehemalige NSDAP-Leute auf. 1954 waren 27 Prozent aller Mitglieder der kommunistischen Staatspartei zuvor in der Hitler-Partei und deren Gliederungen gewesen. Und 32,2 Prozent aller damaligen Angestellten im Öffentlichen Dienst gehörten früher einmal nationalsozialistischen Organisationen an.

- ^ Sabine Pannen. ""Wo ein Genosse ist, da ist die Partei!"? – Stabilität und Erosion an der SED-Parteibasis" (PDF). Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Heike Amos, Politik und Organisation der SED-Zentrale 1949–1963: Struktur und Arbeitsweise von Politbüro, Sekretariat, Zentralkomitee und ZK-Apparat, LIT Verlag, Berlin/Hamburg/Münster 2003, ISBN 978-3-82586-187-2, p. 65.

- ^ Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- ^ Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- ^ Spiegel: Magazin meldet Spur in Liechtenstein.

- ^ Franz Oswald 2002, The Party That Came Out of the Cold War, pp. 69–71.

External links

[edit] Media related to Socialist Unity Party of Germany at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Socialist Unity Party of Germany at Wikimedia Commons

- Socialist Unity Party of Germany

- Defunct communist parties in Germany

- Political parties in East Germany

- Parties of one-party systems

- Political parties established in 1946

- Political parties disestablished in 1990

- Formerly ruling communist parties

- Eastern Bloc

- 1946 establishments in Germany

- 1990 disestablishments in East Germany

- Peaceful Revolution