Bobby Jameson

Bobby Jameson | |

|---|---|

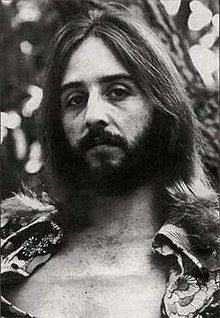

Jameson photographed for a 1972 Rolling Stone magazine article | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Robert Parker Jameson |

| Also known as | Bobby James Chris Lucey Jameson |

| Born | April 20, 1945 Geneva, Illinois, U.S. |

| Origin | Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Died | May 12, 2015 (aged 70) San Luis Obispo, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar |

| Years active | 1963–1985 |

| Labels | Jolum, Talamo, Decca, Brit, Surrey, Mira, Current, Penthouse, Verve, GRT |

| Website | bobbyjameson |

Robert Parker Jameson[1] (April 20, 1945 – May 12, 2015) was an American singer-songwriter who was briefly promoted as a major star in the early 1960s and later attracted a cult following with his 1965 album Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest, issued under the name Chris Lucey. The album's dark lyrics and sophisticated arrangements led its advocates to note similarities with Love's 1967 album Forever Changes.[2] For decades, little was known about Jameson or his origins, and he was more famous for engaging in public disturbances and suicide attempts than his music.[3][4]

Starting his career in 1963, Jameson was hyped as the next major pop event in an elaborate promotional campaign that ran in the magazines Billboard and Cashbox. For the next five years, he released 11 singles across eight different American and British record labels. At one point, he was the opening live act for the Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, and Chubby Checker, and also declined an offer to join the Monkees.[5] From the mid 1960s to early 1970s, Jameson was active in Los Angeles underground music circles, working with musicians such as Frank Zappa and members of Crazy Horse. During this period, he participated in the Sunset Strip riots, appeared as a subject in the 1967 documentary Mondo Hollywood, and garnered a reputation as someone who had ruined his chances at success. After Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest, he released only two more albums: Color Him In (1967), a collaboration with Curt Boettcher, and Working (1969), an album of cover songs.

Jameson's life was affected by personal misfortune, followed by alcoholism and criminal activity. He grew increasingly frustrated and disillusioned with the music industry, alleging that his managers and employers failed to ensure him financial compensation and royalties, and that some companies had illegally claimed the intellectual property rights to his songs. For much of the 1970s he was institutionalized or homeless, but eventually achieved sobriety. After 1985, he left the music business completely, and was rumored to be dead for many years. In 2002, Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest was reissued without Jameson's knowledge, and in response, he resurfaced in 2007 with a series of autobiographical blog posts and YouTube videos, which he maintained until his death in 2015.[6]

Childhood

[edit]Bobby Jameson was born in Geneva, Illinois, but by the age of 10 was living with his mother, stepfather and brother in Tucson, Arizona. He and his brother began to learn guitar and entered talent contests, before his parents divorced. The brothers and their mother then lived in various small towns in Arizona, before moving to Glendale, California in 1962.[7]

Music career

[edit]Early singles and promotion

[edit]Credited as Bobby James,[8] he made his first record, "Let's Surf", with Elliot Ingber on guitar, on the Jolum label in 1963.[7]

In 1964, while sharing a house in Hollywood with Danny Whitten, Billy Talbot, and Ralph Molina (later of Crazy Horse), Jameson met Tony Alamo, who became his manager and promised to make him a star. Alamo mounted a major promotional campaign in the music press, describing the 19-year-old Jameson as "The Star Of The Century" and "The World's Next Phenomenon". Jameson later wrote:

For some reason, that is still a mystery to me to this day, Tony just started promoting me in Billboard and Cashbox magazine without ever telling me he was going to do it. He just showed up one day in a coffee shop in Hollywood with a copy of both publications and I was in them. We had no contract, no agreement of any kind and no record. But there I was, world wide in both mags. I don't know what I can say to describe how weird it was to be nobody and then have that happen....The ads continued to run for 9 weeks doubling in size with each new edition. Half page, three quarter page, full page and so on. By the 8th week the ad ran in Billboard only and was a 4 page, full color fold out...[9]

Jameson recorded a single for Alamo's label, Talamo, "I'm So Lonely" / "I Wanna Love You", both self-penned songs. The record became a regional hit in the Midwest and Canada, and as a result he opened shows for The Beach Boys and Chubby Checker, and appeared on American Bandstand. However, the follow-up, "Okey Fanokey Baby", was less successful, and Jameson wanted to get away from Alamo's increasingly manipulative behavior.[nb 1]

As a friend of P.J. Proby, who had already achieved success in Britain, Jameson traveled to London, where Andrew Loog Oldham had expressed an interest in recording him. There, he recorded "All I Want Is My Baby", co-written by Oldham and Keith Richards and probably featuring session guitarist Jimmy Page, with a Jagger/Richards B-side, "Each and Every Day of the Year".[10] After appearing on the TV show Ready Steady Go!, featuring his gimmick of wearing a glove on only one hand, he stayed in London and in 1965 recorded "Rum Pum" / "I Wanna Know", produced by Harry Robinson, for the Brit Records label set up by Chris Peers and Chris Blackwell. Again, however, it was unsuccessful and Jameson returned to Los Angeles.[7][9]

Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest

[edit]After his return to California, Jameson was approached by Mira Records, a company established by Randy Wood, previously of Vee-Jay Records. They had recorded an album, Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest, with another singer-songwriter, Chris Ducey, for release on their mid-price subsidiary Surrey label. The album sleeves had already been printed, with Ducey's name and the track titles, but with a photo showing Brian Jones. However, in the meantime Ducey had entered into another contract with a different company, which meant that Mira were unable to release Ducey's record. The label asked Jameson — who at the time was "broke, homeless, and sleeping on people's couches"[11] — to write and record new songs to match Ducey's song titles, and arranged to have the record sleeves overprinted so that the name "Ducey" would appear as "Lucey". Within two weeks, Jameson wrote the songs, and recorded them with producer Marshall Leib (previously a member of The Teddy Bears with his friend Phil Spector). The record was released without fanfare, with Jameson credited as songwriter, but without any agreement over his legal rights to the recordings. It was later issued on the Joy label in the UK under Jameson's own name, and the title Too Many Mornings.[10][9][nb 2]

Although Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest was not promoted commercially, and was ignored when first released in late 1965, over the years it acquired a strong reputation. According to Dean McFarlane at Allmusic:

This sought after psychedelic pop gem... [is] often compared to Love's Forever Changes, in that it is an intricate exploration of sophisticated arrangements and bleak and twisted lyricism... [It] may have been a little too courageous for its time, tackling blues, exotic - almost lounge arrangements and pure pop psychedelia. Its beauty is in its absolute fracture and collage of a million and one ideas.[2]

Richie Unterberger wrote:

There aren't many albums of the time that bear an unmistakable Love similarity, but Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest is one of them. Both the vocals and songwriting bear strong recollections of early Arthur Lee, with the melodic but wistful folk-rock chord changes, occasional Latin jazz tempos, occasional gruff folk-blues downbeat atmosphere, probing yet vague lyrics, and oddball production.[14]

Part of its appeal to record collectors was its obscurity[2] and that little was known about its creator. Jameson himself commented: "[The album] was a throw away album when it was created. Like it or not, that is a fact. It has, in recent years, taken on a life of its own and for that I am grateful, but it needs to be viewed in real context, to see how it has risen on its own merit to a position it never held when it was created."[11]

"Vietnam" and Mondo Hollywood

[edit]Early in 1966, Jameson recorded (under his own name) a single for the Mira label, "Vietnam" / "Metropolitan Man", on which he was backed by members of The Leaves, who had recorded Jameson's song "Girl from the East" on their own album, Hey Joe. In 2010, writer Jon Savage described "Vietnam" as "an all-time garage-punk classic – a vehement statement against a war that, by early 1966, was already spiralling out of control."[15] However, at the time the record was barely promoted and did not receive airplay because, according to Jameson, its sentiments were seen as too contentious, and Jameson himself had a reputation as someone who had blown his chances of success.[16] In addition to The Leaves, playing drums on the recording session for "Vietnam" was the elusive musician Don Conka from the group Love.[17][18]

Jameson was featured, along with many others, in the experimental 1967 documentary movie Mondo Hollywood, directed by Robert Carl Cohen, in which he talked about his beliefs and career, and was filmed with his then-girlfriend Gail Sloatman (later the wife of Frank Zappa) and recording "Metropolitan Man".[7] He also made a brief uncredited cameo in the 1967 CBS documentary Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution.[19]

Zappa, Color Him In, and Working!

[edit]

Later in 1966, Jameson recorded two singles for the Penthouse label, a Mira subsidiary, owned by Ken Handler and Norm Ratner.[20] Both the singles, "Reconsider Baby" and "Gotta Find My Roogalator", were arranged and produced by an uncredited Frank Zappa, who also played guitar, with other musicians including Carol Kaye and Larry Knechtel. Jameson also recorded a single, "All Alone", for Current Records. However, none of the records were commercially successful. According to Jameson, Handler dropped him from the label after Jameson turned down a sexual advance.[21] At about the same time, he was considered for one of the roles in The Monkees, but decided not to pursue the opportunity, and for a time became actively involved in anti-Vietnam War protests in Los Angeles.[9] One report at the time stated that "his outspokenness and active participation in the recent Sunset Strip riots has acquired him the honorary title 'Mayor of the Sunset Strip'".[22]

He began working with arranger and producer Curt Boettcher on an album, Color Him In. The album, credited simply to Jameson, was released in early 1967 by Verve Records as a result of Jameson's connections with Zappa. Two singles on the Verve label, "New Age" and "Right By My Side", followed that year. However, Verve were unwilling to release Jameson's later recordings, and he left the label in 1968. By this time, Jameson was making increasing use of LSD, other drugs and alcohol, and was arrested 27 times, being charged at one point with assaulting a police officer.[23][24] In 1968, he recorded his last album, Working!, for the small GRT label, with musicians including James Burton, Jerry Scheff and Red Rhodes.[10]

Personal struggles

[edit]Increasingly, Jameson became frustrated and disillusioned with the fact that he had never received any financial rewards from his music. He was hospitalized several times after drug overdoses and other suicide attempts, detailed in his later blog. He also intermittently made unreleased recordings, with Jesse Ed Davis, Ben Benay and others, and in 1972 featured in an article about his life and personal troubles in Rolling Stone magazine.[23] For much of the 1970s he was either institutionalized, or living on or close to the streets, and making several attempts to give up alcohol and drugs. He recorded several tracks for RCA in the late 1970s, but they were unreleased, aside from one single issued as Robert Parker Jameson. In 1985, he left the music business completely.[7]

Final years and death

[edit]For the next twenty years, he lived quietly with his mother in San Luis Obispo County, California, overcoming his alcoholism. In 2003, he discovered that Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest had been released on CD without his knowledge. Before then, he was rumored to be dead by many who knew him. He was brought back to the public eye by music historian Steve Stanley, who conducted a private investigation into Jameson's whereabouts.[3] In 2007, Jameson started a blog, detailing his life and his continuing attempts to seek some financial recompense for his earlier recordings.[19]

On May 12, 2015, Jameson died in San Luis Obispo, aged 70, of an aneurysm in his descending aorta.[19]

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]- Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest (as Chris Lucey, Surrey, 1965; issued in UK on Joy label as Too Many Mornings by Bobby Jameson)

- Color Him In (as Jameson, Verve, 1967)

- Working! (GRT, 1969)

Singles

[edit]- "Let's Surf" / "Please Little Girl Take This Lollipop" (as Bobby James, Jolum, 1963)

- "I Wanna Love You" / "I'm So Lonely" (Talamo, 1964; issued in UK on London label)

- "Okey Fanokey Baby" / "Meadow Green" (Talamo, 1964)

- "All I Want Is My Baby" / "Each And Every Day of the Year" (Decca (UK), 1964)

- "Rum Pum" / "I Wanna Know" (Brit (UK), 1965)

- "Vietnam" / "Metropolitan Man" (Mira, 1966)

- "All Alone" / "Your Sweet Lovin'" (Current, 1966)

- "Reconsider Baby" / "Lowdown Funky Blues" (Penthouse, 1966)

- "Gotta Find My Roogalator" / "Lowdown Funky Blues" (Penthouse, 1966)

- "New Age" / "Places Times and the People" (as Jameson, Verve, 1967)

- "Right By My Side" / "Jamie" (as Jameson, Verve, 1967)

- "Palo Alto" / "Singing The Blues" (GRT, 1969)

- "Stay With Me" / "Long Hard Road" (as Robert Parker Jameson, RCA, 1978)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Alamo later became an evangelical cult leader and convicted child sex offender.

- ^ The real Chris Ducey became a member of The Penny Arkade, who recorded an unreleased album with Mike Nesmith, and was later a member of Prairie Madness.[12] He released a solo album, Duce of Hearts, in 1975.[13]

Citations

- ^ Some sources give his name as Robert James Parker, but his own site states Robert Parker Jameson as his "full name".

- ^ a b c McFarlane, Dean. "Songs of Protest and Anti-Protest". AllMusic.

- ^ a b Stanley, Steve (2003). "The Return of an LA Legend". Mojo. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

- ^ Rhoades, Lindsey (July 25, 2017). "Q&A: Ariel Pink On Trump, Madonna, & His New Album Dedicated To Bobby Jameson". Stereogum.

- ^ Blush, Steven (April 12, 2016). "This Guy Wrote a Book About Fame and Oblivion So We Asked Him to List Five Artists History Forgot". Vice.

- ^ Geslani, Michelle (June 21, 2017). "Ariel Pink announces new album, Dedicated to Bobby Jameson, shares video for "Another Weekend" — watch". Consequence of Sound.

- ^ a b c d e Jan (2010). "Psychedelic Central: Bobby Jameson". Archived from the original on April 23, 2011.

- ^ Label shot of "Let's Surf". Accessed 17 April 2011

- ^ a b c d Hollywood A Go Go: Bobby Jameson's story Archived December 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 April 2011

- ^ a b c Ankeny, Jason. "Bobby Jameson". AllMusic. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Jameson, Bobby (March 16, 2008). "(part 40) CHRIS LUCEY, THE LITTLE ALBUM THAT COULD". Blogspot. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Donald F. Glut, The Penny Arkade story Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 April 2011

- ^ "Duce of Hearts". AllMusic. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Chris Lucey". AllMusic. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Savage, Jon (November 10, 2010). "Bobby Jameson rages against the Vietnam war". The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Jameson, Bobby (March 18, 2008). "(part 41) LSD, DOWNERS, AND VIETNAM... A NEW BEGINNING". Blogspot. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ AllMusic - Don Conka, Artist Biography by Eugene Chadbourne

- ^ Night Flight, May 20, 2015 - Remembering “Mondo Hollywood”‘s Bobby Jameson By Bryan Thomas Archived 2015-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Thomas, Bryan (May 21, 2015). "Remembering "Mondo Hollywood"'s Bobby Jameson". Nightflight. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Penthouse". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Porter, Maximilano (2018). Losers: Historias de famosos perdedores del rock. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Argentina. ISBN 9789877800005. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ Koslow, Ron (April 22, 1967). "Bobby Jameson: Prophet in Leather". The Beat. p. 7. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Sims, Judith (October 26, 1972). "When Your Manager Turns Jesus Freak". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Jameson, Bobby (June 3, 2008). "(part 75) ASSAULT ON A PEACE OFFICER: 2 COUNTS". Blogspot. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Bobby Jameson discography at Information Is Not Knowledge website. Accessed 16 April 2011

- ^ "Bobby Jameson Discography - USA - 45cat".

External links

[edit]- bobbyjameson

.blogspot .com – Jameson's original blog, active from 2007 to 2015 - "2011 complaint Bobby Jameson" on YouTube

- 1945 births

- 2015 deaths

- American male singer-songwriters

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- Guitarists from Arizona

- Guitarists from Illinois

- Musicians from Tucson, Arizona

- Singer-songwriters from Illinois

- American outsider musicians

- People with hypoxic and ischemic brain injuries

- Deaths from aortic aneurysm

- 20th-century American guitarists

- American male guitarists

- 20th-century American male singers

- Singer-songwriters from Arizona