Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

Chippewas of the Thames First Nation 42

Deshkaan-ziibing Aniishinaabeg | |

|---|---|

| Chippewas of the Thames First Nation Indian Reserve No. 42 | |

| Coordinates: 42°50′N 81°29′W / 42.833°N 81.483°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Middlesex |

| First Nation | Chippewas of the Thames |

| Formed | 1819 |

| Government | |

| • Chief | R.K. Joe Miskokomon |

| • Federal riding | Lambton—Kent—Middlesex |

| • Prov. riding | Lambton—Kent—Middlesex |

| Area | |

| • Land | 39.11 km2 (15.10 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

• Total | 762 |

| • Density | 19.5/km2 (51/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal Code | N0L |

| Area code(s) | 519 and 226 |

| Website | www.cottfn.com |

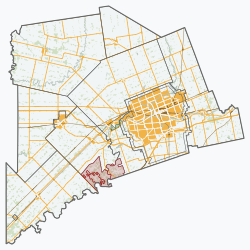

Chippewas of the Thames First Nation (Ojibwe: Deshkaan-ziibing Aniishinaabeg) is an Anishinaabe (Ojibway) First Nations band government located 24 kilometres (15 mi) west of St. Thomas, in southwest Ontario, Canada. Their land base is the 3,652.60 hectares (9,025.8 acres) Chippewas of the Thames First Nation 42 reserve, which almost entirely surrounds the separate reserve of Munsee-Delaware 1. As of January 2014, their registered population is 2,738 people with 957 living on reserve.

Chippewas of the Thames are neighbours with the Munsee-Delaware Nation, and with the Oneida Nation of the Thames who refer to the territory under the jurisdiction of the Ojibway as twaˀkʌnhá·ke.[2]

Territory

[edit]According to Chippewas of the Thames consultation protocol called "Wiindmaagewin", its traditional/ancestral lands, "Traditional Anishinaabe territory in southwestern Ontario north of the Thames River includes the 2.78 million acres marked on treaty maps concerning the Longwoods (1822) and Huron (1827) tracts.[3] In addition, south of the Thames River, the traditional territory also includes the lands addressed in the McKee Treaty (1790), the London Township Treaty (1796), and the Sombra Township Treaty (1796). Deshkan Ziibiing is a party with other Anishinaabe nations to several of these treaties, but is the sole Anishinaabe party to the Longwoods Treaty.[4]

As recognized in these treaties, the ancestral lands of Deshkan Ziibiing thus include all the lands and waters between Lake Huron to the north and Lake Erie to the south, and stretching eastward from the eastern banks of the St. Clair and Detroit rivers to the Mississaugas of New Credit 1792 Treaty lands, a line running northwards from Point Bruce on the Erie shore, to Point Clark on the Huron shore. In addition, Deshkan Ziibiing territory extended into what are now the American states of Michigan and Ohio. Historically, we [Anishinaabek] managed portions of our territory in common with other Anishinaabe nations, and at times in partnership with the Haudenosaunee. Nevertheless, the lands bordering the northern bank of the Thames River have been solely in the stewardship and possession of Deshkan Ziiibiing since before the treaty era."[4]

Chippewas of the Thames First Nation Treaties, Lands and Environment Department has a Treaty Research Unit responsible for researching Chippewas of the Thames' history. All treaties, Chippewas of the Thames First Nation is signatory to, are pre-Confederation treaties. That is to say they were negotiated and signed before Canada's Confederation in 1867. While Canada's government structure has changed significantly from the early days of British colonialism to the present, a continuous political tradition can be identified. This tradition is commonly represented through the British Monarch and their representatives often referred to as the Crown. Land claims research indicates the Crown representatives did not always properly uphold their treaty obligations. It is therefore the job of researchers to provide the historical information required to take legal action against the Crown.

Chippewa members can train to be Archaeology Field Liaison or Archaeology Monitors. The monitors learn to identify features, remains, types of chert and the tools previously used by ancestors of Chippewas of the Thames people, as well as various methods for testing and excavating archaeology sites. This training is provided by the Ontario Archaeology Society. Archaeology assessments are mandatory for developers, municipalities and other entities wanting to develop

History

[edit]In 1763, Chief Seckas of the Thames River brought 170 warriors to the siege of Detroit during Pontiac's uprising. The reserve was established in 1819, as part of a treaty by which the Chippewas of the Thames agreed to share 552,000 acres (2,234 km2) of land with the British for an annuity of £600 and the establishment of two reserves, of which reserve no. 42 is larger. In 1840 the Chippewas reached an agreement with the Munsee-Delaware Nation to allow the Munsee to live on 1 square mile near the Thames river. The Munsee portion of the reserve became part of the new Munsee-Delaware Nation No. 1 reserve in 1967.[citation needed]

Aboriginal Rights, Treaty Rights and Title Rights at Chippewas of the Thames

[edit]Assertion Activities

[edit]DUTY TO CONSULT AND ACCOMMODATE

Issue: Crown did not consult Chippewas of the Thames First Nation as per its obligations under Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution. Instead, the National Energy Board which is a delegated authority acting as a tribunal made a decision that ignored or is contrary to the Crown's constitutional obligations to Aboriginal Peoples to consult and accommodate Aboriginal Peoples. The decision was taken to the Supreme Court of Canada and heard November 30, 2016.

Context: Chippewas of the Thames First Nation is the single signatory to the Longwoods Treaty which includes title to the lands and waterbed of Deshkan Ziibi (Thames River). The NEB authorized Enbridge Pipelines Inc. to reverse the flow of a section of pipeline between North Westover, Ontario and Montreal, Quebec: and, to expand the annual capacity of Line 9; and, to allow heavy crude to be shipped on Line 9 and did not "express an opinion as to whether the Crown had a duty to consult or accommodate in respect of the Proposed Project or, more importantly, whether the Crown had fulfilled its duty to consult"[5] given the potential harm the decision could have on the overall health of the river. The pipeline crosses the river within the Longwoods Treaty Territory.

Timeline:

2017-July-26: Appeal dismissed by SCC, stating, "A majority of the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal, finding that, in the absence of the Crown as a participant in the original application, the NEB was not required to determine whether the Crown was under a duty to consult, and if so, whether the duty had been discharged. Nor was there any delegation by the Crown to the NEB of any power to undertake the fulfillment of any such duty. In dissent, Rennie J.A. would have allowed the appeal, concluding that the NEB was required to undertake a consultation analysis as a precondition to approving Enbridge's application."[6] After the Chippewas of the Thames community filed suit against Enbridge to stop its controversial pipeline through Chippewas land, in July 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada ordered the community of 3,000 to pay Enbridge's legal costs.[7]

2015-October-20: Federal Court of Appeal upheld the National Energy Board's decision to allow Enbridge Inc. to modify its Line 9B pipeline.

Environment

[edit]Chippewas of the Thames First Nation is part of the Thames River watershed. Dawson Creek, Hogg Creek and Big Monday Creek are three of many creeks running into the Thames River through the community.

Chippewas of the Thames First Nation Environment Unit conducts Benthic sampling at 17 locations within the community. Benthic sampling measures the organisms (bugs) that live in the sediment in the top layer of the riverbed (also called the Benthic Zone) as an indicator of water quality. Chippewa uses the same collection protocols used at the Upper and Lower Thames Conservation Authorities which are a 3-minute 'Kick and Sweep' method, bugs preserved in 95% ethanol and samples taken to the lab for identifications. The amount and type of bugs found, indicate the water quality based on the Family Biotic Index (FBI). The FBI reflects the bugs varying tolerance to water pollution. The average Benthic Water Quality Rating for Chippewas of the Thames First Nation is 5.66, this rates Chippewa's average water quality as 'Fair'.

Chippewa of the Thames First Nation has had a recycling program in place for many years. It has grown from a drop-off location to a weekly curbside recycling pick-up program. In the May 2019 Treaties, Lands & Environment Department BiAnnual Newsletter May 2019, it was reported that 97 cubic yards of landfill space was avoided, 506,110 litres of water saved, 451 trees saved and 36,268 pounds of air pollutants avoided.

Through ongoing relationship building with the Lower Thames Valley Conservation Authority (LTVCA), free parking permits to the LTVCA public conservation areas were granted to Chippewas of the Thames First Nation band members as of April 1, 2019.

Governance

[edit]Chippewas of the Thames First Nation's Chief and Council are elected officials who serve 2-year terms of office. Elections are held in July on the odd-numbered years. [citation needed]

Listing of Elected Chiefs and Councillors

[edit]2023-2025: Chief R.K. Joe Miskokomon, Councillors Denise Beeswax, Alanis Deleary, Heather Nicholas, Kingson Huff, Betsy Kechego, Leslee White-eye, Michelle Burch, Gene Hendrick, Felicia Huff, Warren Huff, Evelyn Young, Monica Hendrick

2021-2023: Chief Jacqueline S. French, Councillors Kingson Huff, Allan (Myeengun) Henry, Betsy L. Kechego, Alanis R. Deleary, Warren A. Huff, Michelle Burch, Denise Beeswax, Clinton G. Albert, Terri N. Fisher, Crystal P. Kechego, Gene A. Hendrick, Evelyn G. Young

2019-2021: Chief Jacqueline S. French, Councillors Kingson Huff, Darlene Whitecalf, Warren Huff, Leland Sturgeon, Michelle Burch, Adam Deleary, Terri Fisher, Rawleigh Grosbeck, Denise Beeswax, Kodi Chrisjohn, Beverly Deleary, Election held on July 20, 2019.

2017-2019: Chief Arnold Allan (Myeengun) Henry, Councillors Raymond Deleary, Jacqueline French, Warren Huff, Darlene Whitecalf, Larry French, Carolyn Henry, Beverly Deleary, Michelle Burch, Kodi Chrisjohn, Denise Beeswax, Rawleigh Grosbeck, Leland Sturgeon.[8]

2015-2017: Chief Leslee White-Eye (née Henry), Councillors Arnold Allan (Myeengun) Henry, Murray Kechego II, George E. Henry, Clinton Albert, Raymond Deleary, Betsy Kechego, Carolyn Henry, Larry French, Joe Miskokomon, Jacqueline French, Darlene Whitecalf, Monty McGahey II

2013-2015: Chief R.K. Joe Miskokomon, Councillors Allan (Myeengun) Henry, Betsy Kechego, Clinton G. Albert, Darlene Whitecalf, George E. Henry, Nancy Deleary, Larry French, Felicia Huff, Beverly Deleary, Warren Huff, Rawleigh Grosbeck Sr., Shane Henry

2011-2013: Chief R.K. Joe Miskokomon, Councillors Arnold Allan (Myeengun), Darlene Whitecalf, Betsy Kechego, Warren Huff, Beverly Deleary, Katrina Fisher, Rawleigh Grosbeck, Shane Henry, Evelyn Albert, Harley Nicholas, Richard Riley, Nancy Deleary

Women Elected Chiefs at Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

[edit]1st Elected Woman Chief of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

Arletta Silver (née Riley) was elected in a bi-election held on August 20, 1952, with a total of 15 votes being cast with 10 votes counted for Arletta and 5 for Fred Kechego. In an Indian Affairs record of Election of Chief, dated August 21, 1952, it states Arletta Silver was nominated by Mrs. Wilson Fox and seconded by Rosa Deleary. She ran against Fred Kechego who was nominated by Clarence Silver and seconded by Edward Hall. The letter signed by R.J. Stallwood, Supt., Caradoc Indian Agency, Muncey, Ontario confirms the bi-election results and that the nomination for the elections of a Chief was to fill the vacancy created by the resignation of Chief Clarence Silver and that nominations were held on August 13, 1952. A news report in The Lethbridge Herald on Saturday, May 2, 1953, identifies Arletta Silver as being in the role of Chief for a year amid a revised Indian Act policy that "gave Indian women their franchise" in 1951. The Lethbridge news report also indicated that Chief Clarence Silver resigned due to ill health.

In 2015, Leslee White-Eye (née Henry) was elected chief of Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, the second woman chief to be elected in over 63 years. She follows Arletta Silver (née Riley) who was elected in a bi-election held on August 20, 1952, and Starr McGahey-Albert (20xx) was appointed in the role of chief due to the elected Chief of the day being unable to fulfill his duties due to illness. Leslee White-Eye is the daughter of George E. Henry and Theresa E. Henry (née Deleary) both Chippewas of the Thames First Nation members. During her term, she was able to finalize the community benefit agreement amendments with the City of Toronto over the Greenlane Landfill site resulting in monies held in trust since 2009 to be released in December 2016 to the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation community for their benefit. Also during her tenure, Chief White-Eye sought nation attention in the community's Supreme Court case Chippewas of the Thames First Nation vs. Enbridge et al. She was able to garner full support from Chiefs-in-Assembly resolutions from the Anishinaabek Nation/Union of Ontario Indians, Chiefs of Ontario and Assembly of First Nations to proceed with leave to appeal to the Supreme Court. In response, to the ongoing legal proceedings, Chippewas of the Thames approved the nation's Duty to Consult Protocol, Wiindmaagewin, in 2016 which outlines the expectations the nation has regarding proponent and government relations with the nation. In addition, Chief White-Eye led the political work behind the signing of an Agreement-in-Principle with the province of Ontario on July 20, 2017, in tobacco self-regulation on-reserve in July 2017. The self-regulatory work situates the tobacco sector on-reserve as a legitimate economic sector worthy of legislative frameworks to make it so. This is in direct opposition to the federal government's response to on-reserve un-marked tobacco sales as 'contraband' and making it a criminal act as of 2015. On July 13, 2017, Chief White-Eye was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws, honoris causa (LLD) at Western University as an emerging leader in the region, particularly for her work to improve municipal-nation relations with the City of London.

In 2019, Chief Jacqueline S. French was Chippewa's 3rd elected woman chief. She is in her 2nd term as Chief at Chippewas of the Thames First Nation.

Education

[edit]Chippewas of the Thames First Nation administers a K-8 elementary school called Antler River Elementary, formerly known as Wiiji Nimbawiyaang Elementary (meaning 'together, we are standing' in Ojibwe).

Life Long Learning Education System Delivery

[edit]Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) Language Acquisition

[edit]Beginning in 2017–2018, an immersion program was implemented beginning in Junior Kindergarten. Each subsequent year, another grade was added. In 2019–2020, the grade 1 students would have received three years of Anishinaabemowin immersion instruction This was an extension of the Early Years language program that first began to implement a language program for its toddler program a few years earlier. Due to a number of reasons including shortage of language immersion teachers, curriculum and funding, the immersion program was paused in Fall 2021.

Education Governance

[edit]1991 - The Creation of the Board of Education

[edit]Following a school evaluation conducted by Dr. Ron Commons and input from Chippewas of the Thames First Nation citizens, Chief and Council in 1991 put in motion the eventual delegation of decision-making over education affairs for the nation to a school board. On June 18, 1991, the Chippewas of the Thames Band Council approved the following motion of council:

Moved by Harley Nicholas, seconded by George E. Henry that this Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation approves Dr. Ron Commons, executive summary recommendations for the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation.

Approximately, four months later on October 8, 1991, the Chippewas of the Thames Band Council passed the following motions of council:

Motion 5

Moved by Joe Miskokomon, seconded by Monica Hendrick that this Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation approves the development of the director of education including terms and conditions, responsibilities, relationship and finances.

Motion 6

Moved by Mark French, seconded by Terry Henry that this Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation hold quarterly meetings between the Chief and Council and the School Board.

In addition, the following motions were amended on October 29, 1991, and passed,

Motion 1

Moved by Harley Nicholas, seconded by Terry Henry that this Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation appoints Monica Hendrick to act as liaison person to the School Board.

Motion 2

Moved by Harley Nicholas, seconded by Terry Henry that this Council of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation have the School Board take over the Education System in finance, personnel, administration and curriculum development as well as the Day Care system.

Subsequently, on June 30, 1993, a Board Management policy went into place. It also further identified the partnership between the Board of Education and Chief and Council to assist each other in joint education matters that arise, e.g. finances, school building, etc.[9]

Listing of Board of Education Trustees

2021-2023 Alexis Albert, Mary Deleary, JoAnn Henry, Felicia Huff, Karsyn Summers. Council Liaison TBD

2019-2021 Ken Albert II, Mary Deleary, JoAnn Henry, Dusty Young, Evelyn Young, Council Liaison Michelle Burch

Demographics

[edit]In April 2004, the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation had a registered population of 2221, of whom 876 lived on the reserve. By January 2011, the Nation had a total registered population of 2462, of whom 911 lived on the reserve.[10]

| 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Population | 0 (+0.0% from 2016) |

| Land area | 42.49 km2 (16.41 sq mi) |

| Population density | 0/km2 (0/sq mi) |

| Median age | 0.0 (M: , F: ) |

| Private dwellings | 0 (total) 0 (occupied) |

| Median household income |

Notable members

[edit]- Cody McCormick, ice hockey player for the Buffalo Sabres

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Chippewas of the Thames First Nation 42 community profile". 2011 Census data. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ Michelson, K., & Doxtator, M. (2019). ”Chippewa; non-Oneida Indian; on the Chippewa side, at the Chippewa reserve on the other side of the river from Oneida-of- the-Thames”. In Oneida-English/English-Oneida Dictionary (p. 935). essay, University of Toronto.

- ^ Wiindmaagewin

- ^ a b Deshkan Ziibiing/Chippewas of the Thames First Nation Wiindmaagewin Consultation Protocol Final November 26, 2016

- ^ Factum of the Appellant, File No.36776, to the Supreme Court of Canada, July 20, 2016.

- ^ Supreme Court of Canada (n.d.) Chippewas of the Thames First Nation v. Enbridge Pipelines Inc., et al. Document 36776. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.scc-csc.ca/case-dossier/info/sum-som-eng.aspx?cas=36776

- ^ "Chippewas must pay energy giant's legal bills in lost court battle". CBC News. Canada. July 28, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- ^ "Chief and Council". Chippewas of the Thames First Nation. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Chippewas of the Thames (1999). Chippewas of the Thames Board of Education Profile 1999. Chippewas of the Thames First Nation: Chippewas of the Thames First Nation. p. 6.

- ^ Indian and Northern Affairs Canada - First Nation Profiles: Registered Population Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

- ^ "2021 Community Profiles". 2021 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. February 4, 2022. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ "2006 Community Profiles". 2006 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. August 20, 2019.

- ^ "2001 Community Profiles". 2001 Canadian census. Statistics Canada. July 18, 2021.