Imperial cult

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may be one of personality in the case of a newly arisen Euhemerus figure, or one of national identity (e.g., Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh or Empire of Japan) or supranational identity in the case of a multinational state (e.g., Imperial China, Roman Empire). A divine king is a monarch who is held in a special religious significance by his subjects, and serves as both head of state and a deity or head religious figure. This system of government combines theocracy with an absolute monarchy.

Historical imperial cults

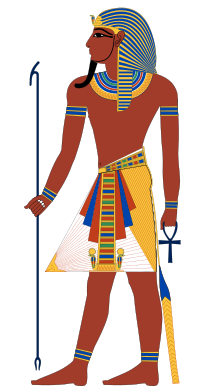

[edit]Ancient Egypt

[edit]The Ancient Egyptian pharaohs were, throughout ancient Egyptian history, believed to be incarnations of the deity Horus; thereby derived by being the son of Osiris, the afterlife deity, and Isis, goddess of marriage.

The Ptolemaic dynasty based its own legitimacy in the eyes of its Greek subjects on their association with, and incorporation into, the imperial cult of Alexander the Great.

Imperial China

[edit]In Imperial China, the Emperor was considered the Son of Heaven. The scion and representative of heaven on earth, he was the ruler of all under heaven, the bearer of the Mandate of Heaven, his commands considered sacred edicts. A number of legendary figures preceding the proper imperial era of China also hold the honorific title of emperor, such as the Yellow Emperor and the Jade Emperor.

Ancient Rome

[edit]

Even before the rise of the Caesars, there are traces of a "regal spirituality" in Roman society. In earliest Roman times the King was a spiritual and patrician figure and ranked higher than the flamines (priestly order), while later on in history only a shadow of the primordial condition was left with the sacrificial rex sacrorum linked closely to the plebeian orders.

King Numitor corresponds to the regal-sacred principle in early Roman history. Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, was heroized into Quirinus, the "undefeated god", with whom the later emperors identified and of whom they considered themselves incarnations.

Varro spoke of the initiatory mystery and power of Roman regality (adytum et initia regis), inaccessible to the exoteric communality.

In Plutarch's Phyrro, 19.5, the Greek ambassador declared amid the Roman Senate he felt instead like being in the midst of "a whole assembly of Kings".

As the Roman Empire developed, the Imperial cult gradually developed more formally and constituted the worship of the Roman Emperor as a god. This practice began at the start of the Empire under Augustus, and became a prominent element of Roman religion.

The cult spread over the whole Empire within a few decades, more strongly in the east than in the west. Emperor Diocletian further reinforced it when he demanded the proskynesis and adopted the adjective sacrum for all things pertaining to the imperial person.

The deification of emperors was gradually abandoned after the Emperor Constantine I started supporting Christianity. However, the concept of the imperial person as "sacred" carried over, in a Christianized form, into the Byzantine Empire.

Ancient and Imperial Japan

[edit]

In ancient Japan, it was customary for every clan to claim descendance from gods (ujigami) and the Imperial Family tended to define their ancestor as the dominant or most important kami of the time. Later in history, this was considered common practice by noble families, and the head members of the family, including that of the Imperial Family, were not seen to be divine. Rather than establish sovereignty by the manner of claimed godhood over the nation however, the Emperor and the Imperial Family stood as the bond between the heavens and the Earth by claims of descending from the Goddess Amaterasu, instead dealing in affairs related with the gods than any major secular political event, with few cases scattered about history. It was not until the Meiji period and the establishment of the Empire, that the Emperor began to be venerated along with a growing sense of nationalism.

- Arahitogami – the concept of a god who is a human being applied to the Emperor Shōwa (Emperor Hirohito as he was known in the Western World), until the end of World War II.

- Ningen-sengen – the declaration with which the Emperor Shōwa, on New Year's Day 1946, (formally) declined claims of divinity, keeping with traditional family values as expressed in the Shinto religion.

In the 16th, 19th, and 20th centuries, Japanese nationalist philosophers paid special attention to the emperor and believed devotion to him and other political causes that furthered the Japanese state was "the greatest virtue".[1] However, in the 14th century, most religious figures and philosophers in Japan thought that excessive veneration of the state and the emperor would consign one to hell.[1]

Ancient Southeast Asia

[edit]Devaraja is the Hindu-Buddhist cult of deified royalty in Southeast Asia.[2] It is simply described as Southeast Asian concept of divine king. The concept viewed the monarch (king) as the living god, the incarnation of the supreme god, often attributed to Shiva or Vishnu, on Earth. The concept is closely related to Indian concept of Chakravartin (wheel turning monarch). In politics, it is viewed as the divine justification of a king's rule. The concept gained its elaborate manifestations in ancient Java and Cambodia, where monuments such as Prambanan and Angkor Wat were erected to celebrate the king's divine rule on earth.[citation needed]

In the Mataram kingdom, it was customary to erect a candi (temple) to honor the soul of a deceased king. The image inside the garbhagriha (innermost sanctum) of the temple often portrayed the king as a god, since the soul was thought to be united with the god referred to, in svargaloka (heaven). It is suggested that the cult was the fusion of Hinduism with native Austronesian ancestor worship.[3] In Java, the tradition of the divine king extended to the Kediri, Singhasari and Majapahit kingdoms in the 15th century. The tradition of public reverence to the King of Cambodia and King of Thailand is the continuation of this ancient devaraja cult.

Examples of divine kings in history

[edit]

Some examples of historic leaders who are often considered divine kings are:

- Africa

- Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt.

- Shilluk Kingdom was ruled by a divine monarchy.

- Ghanas (Kings) of the Empire of Ghana.

- Asia

- God Worshipping Society leader Hong Xiuquan, leader of the Taiping Rebellion, claimed to be Christ's younger brother, and attempted to establish rule as a divine king.

- Korean Buddhist monk Gung-ye, King of Taebong.

- The Japanese emperors up to the end of World War II.

- Javanese Kings during Hindu-Buddhist era (4th–15th centuries AD) such as Sailendra dynasty, Kediri, Singhasari and Majapahit.

- Kings of Khmer Empire, Cambodia

- Srivijaya kings

- Americas

- Kings of the Maya city-states of the Classical period[4]

- Sapa Incas in pre-Hispanic South America; considered descendants of the sun god Inti.[5]

- Oceania

- Kings or Akua Aliʻi of the Hawaiian Islands before 1839

- Europe

- Many Roman emperors were declared gods by the Roman Senate (generally after their death; see Roman imperial cult).

Fictional examples

[edit]- In Warhammer 40,000, the Emperor of Mankind, immortal and perpetual ruler of the Imperium of Man, is worshiped as the deity of the state religion, although he waged a fierce campaign of strict state atheism until the Horus Heresy when the Emperor successfully defeated his fallen son, Horus Lupercal, but was mortally wounded and forced to be interned within the Golden Throne in order to survive.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Conlan, Thomas D. (2022). Spilling, Michael (ed.). Samurai Weapons & Fighting Techniques. London: Amber Books Ltd. p. 113. ISBN 978-1838862145.

- ^ Sengupta, Arputha Rani, ed. (2005). God and King: The Devaraja Cult in South Asian Art & Architecture. National Museum Institute. ISBN 8189233262. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ Drs. R. Soekmono (1988) [1973]. Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed (5th reprint ed.). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 83.

- ^ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Wilfred Byford-Jones, Four Faces of Peru, Roy Publishers, 1967, pp. 17, 50.

References

[edit]- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804748179. OCLC 57577446.

Further reading

[edit]- Ameresekere, H. E. (July 1931). "The Kataragama God: Shrines and Legends". Ceylon Literary Register. Kataragama.org. pp. 289–292. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Baptist, Maria (Spring 1997). "The Rastafari". Buried Cities and Lost Tribes. Mesa Community College. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Effland, Richard (Spring 1997). "Definition of Divine kingship". Buried Cities and Lost Tribes. Mesa Community College. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Effland, Richard; Lerner, Shereen (Spring 1997). "The World of God Kings". Buried Cities and Lost Tribes. Mesa Community College. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Marglin, F. A. (1989). Wives of the God-King: The Rituals of the Devadasis of Puri. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195617312.