Church of Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio

| Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio Parrocchia S. Nicolò dei Greci alla Martorana (Italian) Famullia e Shën Kollit së Arbëreshëvet (Albanian) | |

|---|---|

The Baroque façade, with the Romanesque belltower and Byzantine dome | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Eastern Catholic Churches |

| Province | Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi (Italo-Albanian Catholic Church) |

| Rite | Byzantine Rite |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Co-cathedral |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Palermo, Italy |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Norman-Arab-Byzantine, Baroque |

| Groundbreaking | 1143 |

| Completed | (restoration on 19th century) |

| Official name: Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Reference no. | 1487 |

| State Party | Italy |

| Region | Europe and North America |

The Church of St. Mary of the Admiral (Italian: Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio), also called Martorana, is the seat of the Parish of San Nicolò dei Greci (Albanian: Klisha e Shën Kollit së Arbëreshëvet), overlooking the Piazza Bellini, next to the Norman church of San Cataldo and facing the Baroque church of Santa Caterina, in Palermo, Italy.

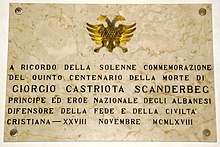

The church is a co-cathedral to the Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi[1] of the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, a diocese which includes the Italo-Albanian (Arbëreshë) communities in Sicily who officiate the liturgy according to the Byzantine Rite in the Koine Greek language and Albanian language.[2] The Church bears witness to the Eastern religious and artistic culture still present in Italy today, further enhanced by the Albanian exiles who took refuge in southern Italy and Sicily from the 15th century under the pressure of Turkish-Ottoman persecutions in Albania and the Balkans. The latter influence has left considerable traces in the painting of icons, in the religious rite, in the language of the parish, in the traditional customs of some Albanian colonies in the province of Palermo. The community is part of the Catholic Church, but follows the ritual and spiritual traditions that largely share it with the Eastern Church.

The church is characterized by a multiplicity of styles that meet, since, through the succession of centuries, it was enriched by various tastes in art, architecture and culture. Today, it stands as a church-historical monument, and subject to protection.

Since 3 July 2015 it has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale.

History

[edit]

The eponym Ammiraglio ("admiral") derives from the Syrian Christian admiral and principal minister of King Roger II of Sicily, George of Antioch, whose palace and property overlapped with the area, and who first patronized its establishment. After approximately 100 years under Arab control, Palermo was named the capital of Kingdom of Sicily. The Norman leaders appreciated the artistic qualities found in the Muslim script and incorporated it into the interiors of their architecture, including in this church. At the same time, Greek was a prevalent language in Mediterranean society, serving as legal language.[3] The foundation charter of the church (which was initially Eastern Orthodox), in Koine Greek and Arabic, is preserved and dates to 1143; construction may already have begun at this point. The church had certainly been completed by the death of George in 1151, and he and his wife were interred in the narthex. In 1184 the Arab traveler Ibn Jubayr visited the church, and later devoted a significant portion of his description of Palermo to its praise, describing it as "the most beautiful monument in the world." After the Sicilian Vespers of 1282 the island's nobility gathered in the church for a meeting that resulted in the Sicilian crown being offered to Peter III of Aragon.[4]

In 1193–94, a female Benedictine convent was founded on adjacent property by the aristocrat Eloisa Martorana. In the first half of the millennium, Sicily underwent a drastic shift as rulers from various dynasties seized control, aggressively expelling Muslims, exemplified by Frederick II's mass deportation of Sicilian Muslims to Lucera.[5] Their drive for cultural homogeneity was reflected in their remodeling of the church. In 1433–34, under the rule of King Alfonso of Aragon, this convent was attached to the church, which has since then been commonly known as La Martorana. The nuns extensively modified the church between the 16th century and the 18th century, making major changes to the structure and the interior decoration.[6] The monastery was suppressed in the 1866 suppression of religious orders.

The nuns of the Martorana were famous for their marzipan, shaped and dyed to resemble various fruits, known as Frutta di Martorana, still sold in pastry shops of Palermo.

In 1937 the church returned to the Byzantine rite with the Albanian community present in Palermo. The church assumed and inherited the title of seat of the parish of the Italo-Albanians in 1945, after the church adjacent to the Italo-Albanian Seminary of Palermo was destroyed in the Second World War. Today, it is still used by the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church for their services and shares cathedral status with the church cathedral of San Demetrio Megalomartire in Piana degli Albanesi. The church was restored and reopened for community worship in 2013. Clergy and congregation were momentarily welcomed in the church of the Santa Macrina of the Italo-Albanian Basilian nuns in Palermo during the restoration works.

The parish of San Nicolò dei Greci does not have a real parish territory, but is the reference point for 15,000 Arbëreshë (the Albanian community of Sicily historically settled in the province of Palermo) residing in the city.

Since 2015, it is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale.

Names

[edit]

The church was traditionally known as "Saint Nicholas of the Greeks", where the term "Greek" meant the adoption of the Byzantine rite and the use of Ecclesiastical Greek as liturgical language, rather than the ethnicity.

The church is now also known as "Parrocchia San Nicolò degli Albanesi", or "Famullia / Klisha e Shën Kollit i Arbëreshëvet në Palermë in Arbëresh language.

Other version include Klisha Arbëreshe Palermë ("The Arbëreshe Church in Palermo") or simply Marturanë. The title "Parrocchia San Nicolò dei Greci alla Martorana" means that the Italo-Albanian parish is now based in the Martorana church, and not at the initial location next to the Italo-Albanian Seminary.

Liturgy and rite

[edit]

The liturgical rites, the wedding ceremonies, the baptism and the festivities religious of the parish of San Nicolò dei Greci follow the Byzantine calendar and the Albanian tradition of the communities of the Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi.[7][8][9]

The languages liturgical used are the koine Greek (as per tradition, which was born to unify all the peoples of the Eastern Church under a single language of understanding) or Albanian (the mother tongue of the parish community). It is not uncommon here to hear the priest and the faithful speaking habitually in Albanian, in fact the language is the main element that identifies them in a specific belonging ethnic. Some young woman from Piana degli Albanesi marries still wearing the rich wedding dress of the Albanian tradition and the ceremony of the marriage (martesa).[10]

A special celebration for the Arbëreshë population is the Theophany or Blessing of the waters on 6 January (Ujët e pagëzuam);[11] the most important festival is Easter (Pashkët), with the oriental rituals of strong spirituality of Holy Week (Java e Madhe) and the singing of Christos anesti – Krishti u ngjall (Christ is risen). On 6 December occurs the feast of Saint Nicholas (Dita e Shën Kollit).[12]

Architecture

[edit]

The original church was built in the form of a compact cross-in-square ("Greek cross plan"), a common variation on the standard middle Byzantine church type. The three apses in the east adjoin directly on the naos, instead of being separated by an additional bay, as was usual in contemporary Byzantine architecture in the Balkans and Asia Minor.[13] In the first century of its existence the church was expanded in three distinct phases; first through the addition of a narthex to house the tombs of George of Antioch and his wife; next through the addition of a forehall; and finally through the construction of a centrally-aligned campanile at the west. The campanile, which is richly decorated with three orders of arches and lodges with mullioned windows, still serves as the main entrance to the church. Significant later additions to the church include the Baroque façade which today faces onto the piazza. In the late 19th century, historically-minded restorers attempted to return the church to its original state, although many elements of the Baroque modifications remain.[14]

Certain elements of the original church, in particular its exterior decoration, show the influence of Islamic architecture on the culture of Norman Sicily. A frieze bearing a dedicatory inscription runs along the top of the exterior walls; although its text is in Greek, its architectural form references the Islamic architecture of north Africa.[15] The recessed niches on the exterior walls are likewise derive from the Islamic architectural tradition. In the interior, a series of wooden beams at the base of the dome bear a painted inscription in Arabic; the text is derived from the Christian liturgy (the Epinikios Hymn and the Great Doxology). The church also boasted an elaborate pair of carved wooden doors, today installed in the south façade of the western extension, which relate strongly to the artistic traditions of Fatimid north Africa.[16] On account of these "Arabic" elements, the Martorana has been compared with its Palermitan contemporary, the Cappella Palatina, which exhibits a similar hybrid of Byzantine and Islamic forms.[17]

Interior

[edit]

The church is renowned for its 12th century mosaics executed by craftsmen working in the Byzantine style. The mosaics show many iconographic and formal similarities to the roughly contemporary programs in the Cappella Palatina, in Monreale Cathedral, and in Cefalù Cathedral, although they were probably executed by a distinct atelier.[18]

The walls display two mosaics taken from the original Norman façade, depicting King Roger II, George of Antioch's lord, receiving the crown of Sicily from Jesus, and, on the northern side of the aisle, George himself, at the feet of the Virgin. The depiction of Roger was highly significant in terms of its iconography. In Western Christian tradition, kings were customarily crowned by the Pope or his representatives; however, Roger is shown in Byzantine dress being crowned by Jesus in the Byzantine fashion. Roger was renowned for presenting himself as an emperor during his reign, being addressed as basileus ("king" in koine Greek). The mosaic of the crowning of Roger carries a Latin inscription written in koine Greek characters (Rogerios Rex ΡΟΓΕΡΙΟΣ ΡΗΞ "king Roger").

The nave dome is occupied by the traditional byzantine image of Christ Pantokrator surrounded by the archangel saints: Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel. The register below depicts the eight prophets of the Old Testament and, in the pendentives, the four evangelists of the New Testament. The nave vault depicts the Nativity and the Death of the Virgin.

The newer part of the church is decorated with later frescoes of comparatively little artistic significance. The frescoes in the middle part of the walls are from the 18th century, attributed to the flemish painter Guglielmo Borremans.

See also

[edit]- Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale

- Arbëreshë

- Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi

- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Concatedral Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio, Palermo, Palermo, Italy (Italo-Albanese)". www.gcatholic.org. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ The liturgical languages of the parish are Koine (Biblical) Greek (as is the tradition for Eastern churches) and Albanian (the language of the Italo-Albanian faithful, the Arbëreshë people).

- ^ Gabrieli, Francesco (1964). "Greeks and Arabs in the Central Mediterranean Area". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 18: 57–65 – via JSTORE.

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 15–21.

- ^ "History of Islam in southern Italy", Wikipedia, 4 January 2024, retrieved 2 April 2024

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 21.

- ^ N° 1 PALERMO, DOMENICA DELL'ORTODOSSIA PRESSO LA CHIESA DELLA MARTORANA, 13 Febbraio 2013

- ^ N°4 DOMENICA DELL'ORTODOSSIA A PALERMO CHIESA DELLA MARTORANA, 13 Febbraio 2013

- ^ III° Domenica di Quaresima Venerazione della Santa Croce, Parrocchia S. Nicolò dei Greci alla Martorana

- ^ Matrimonio in rito bizantino alla Martorana a Palermo

- ^ Tα Άγια Θεοφάνεια, Teofania, Palermo, San Nicolò dei Greci alla Martorana, 6 gennaio

- ^ CHIESA DELLA MARTORANA PALERMO / FESTA DI SAN NICOLA 6 DICEMBRE 2015

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 29–30.

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 42ff.

- ^ For the text of the inscription, see Lavagnini, "L'epigramma."

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 35ff.

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 66.

- ^ Kitzinger, Mosaics, 261-62.

Sources

[edit]- Durose, Steven; Friedman, Sophie; Ochterbeck, Cynthia Clayton (2020). Sicily (in Spanish). Greenville, SC. ISBN 978-2-06-724310-1. OCLC 1155371390.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Patrizia Fabbri, Palermo e Monreale (Bonechi, 2005)

- Irving Hexham and David Bershad, The Christian Travelers' Guide to Italy (Zondervan, 2001)

- Ernst Kitzinger, with Slobodan Ćurčić, The Mosaics of St. Mary's of the Admiral in Palermo (Washington, 1990). ISBN 0-88402-179-3

- Bruno Lavagnini, "L'epigramma e il committente," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 41 (1987), 339–50.

External links

[edit]- Eastern Catholic cathedrals in Italy

- Roman Catholic churches in Palermo

- Arab-Norman architecture in Palermo

- Norman architecture in Italy

- Churches with Norman architecture

- 1151 establishments in Europe

- 12th-century establishments in Italy

- Religious organizations established in the 1140s

- Byzantine mosaics

- World Heritage Sites in Italy

- Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale

- Italo-Albanian Catholic cathedrals