Chicago Portage

| Chicago Portage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Elevation | 589 ft (180 m) |

| Traversed by | Mud Lake (historic), Illinois and Michigan Canal (historic), Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, several railroads, numerous roads including |

| Location | (historic dividing point) 3100 West 31st Street, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, US |

| Range | Valparaiso Moraine |

| Coordinates | 41°50′14″N 87°42′8″W / 41.83722°N 87.70222°W |

The Chicago Portage was an ancient portage that connected the Great Lakes waterway system with the Mississippi River system. Connecting these two great water trails meant comparatively easy access from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River on the Atlantic Ocean to the Rocky Mountains, and the Gulf of Mexico. The approximately six-mile link had been used by Native Americans for thousands of years during the Pre-Columbian era for travel and trade.

In the summer of 1673 members of the Kaskaskia, a tribe of the Illinois Confederation, led French explorers Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette, the first known Europeans to explore this part of North America, to the portage. A strategic location, it became a key to European activity in the Midwest, ultimately leading to the foundation of Chicago.[1]

The Portage crossed waterways and wetlands between the Chicago River and the Des Plaines River, through a gap in the Valparaiso Moraine. In 1848, the water divide was breached by the Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal cutting through the portage, this was deepened and widened in 1900 by the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal which was also used to control the water's directional flow.

Created by a glacier

[edit]

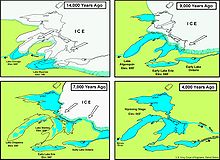

The history of the Chicago Portage begins at the end of the last Ice Age. It was formed as the Wisconsin glaciation retreated northward about 10,000 years ago, leaving behind Lake Chicago (now called Lake Michigan), which was created from the glacier's meltwater.

As the glacier melted and retreated, the water in Lake Chicago rose until it overflowed the southwestern edge of the Valparaiso Moraine, which encircles the lake's southern half, creating the Chicago Outlet River. This was a substantial river, comparable to today's Niagara River, and over time it carved the channel later used by the main and south branch of the Chicago River, the Des Plaines River, and the terrain that became the Chicago Portage.[2][3][4]

As the glacier continued to retreat, it opened another outlet far to the East that became the St Lawrence River. This allowed the emerging lakes to drain even faster, and the Chicago Outlet River dried up leaving the gap in the moraine that served the Chicago Portage.[5]

The Chicago Portage linked what became known as the Chicago River's South Branch and what became known as the Des Plaines River. The point at which the portage crossed the low continental divide that separated waters flowing east toward Lake Michigan from waters flowing west toward the Mississippi River was a wetland that occupied the ancient stream bed of the Chicago Outlet River. Early settlers called this marshy area “Mud Lake”.[6] The total length of the portage was about six miles.[1]

Mud Lake could be wet, dry, marshy, or frozen, depending on the season and the weather, making it at times a difficult, albeit very valuable, transportation route. In very wet weather the water level in both the Des Plaines River and the Chicago River would rise to the point that Mud Lake was flooded, and travelers could traverse the entire six miles by canoe. Usually, however, particularly in late summer, it was necessary to pull out canoes at some point and carry them and all supplies around Mud Lake.[1]

A key to travel and trade in North America

[edit]The Chicago Portage allowed easy access, by boat, to almost all of North America, from the mouth of the St Lawrence River to the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico.[1]

The St Lawrence River divide

[edit]

Until the second half of the 19th century water transportation was virtually the only way to move goods and people around North America. Hence, connections between strategic waterways, usually involving portages, held special importance.[1]

The importance of the Chicago Portage lies in the fact that the channel cut by the Chicago Outlet River created an easy passage over the Saint Lawrence River Divide, the continental divide that separated what had become the Great Lakes waterway system from the Mississippi River waterway system and, as the illustration shows, opened up almost all of what was to become the United States from the Allegheny Mountains to the Rocky Mountains as far south as the Gulf of Mexico.[1]

Early peoples

[edit]Native Americans had used the portage for almost two thousand years before the arrival of Europeans.

The Portage was probably created around 500 BCE[7], p 19 at the end of what is commonly referred to as the Archaic period. Early people had been migrating into the region around the Portage since the Paleo-Indian period, and by the time of the formation of the Portage, these people had begun to create semi-permanent settlements.[7] Archaeological evidence shows that long-distance trade routes had been established. Late Archaic sites that have been uncovered around the Chicago area have revealed shells from the Gulf Coast, galena from the Galena, Illinois, area, and copper from Lake Superior.[8]

The Woodland period (500 BCE – 1,000 CE) followed the Archaic. The Hopewell culture (200 BCE to 500 CE) that arose during this time saw further development of these trade networks as well as the appearance of pottery.[7] Hopewell tribes engaged in extensive trade. This trade network is now called the Hopewell Interaction Sphere, and the part that encompassed Illinois, the Havana Hopewell, played a major part. Since at this time most long-distance travel for trade purposes was via water, it is likely that during this Woodland period the Chicago Portage was first regularly used.[7]

The Mississippian period (1000 – 1600) followed the Woodland. During this time native people built more permanent settlements, and continued to expand trading networks. Cahokia was the largest of these settlements and the best example of how native society was evolving. It was located at the confluence of the Mississippi River, the Missouri River, and the Illinois River and was therefore a key to the trade network that had developed. Given that copper from the northern shores of Lake Superior have been found at archeological digs at Cahokia, and that Mississippian pottery has been found at sites at northern Lake Huron, it is likely that the Chicago Portage was regularly used during this period.[7], p 24

During all of this time early Native Americans found the Chicago Portage to be a convenient transportation route between the Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River in the interior.

The first Europeans

[edit]

By 1673 the French had established a trading post at present day Mackinac Island at the top of Lake Michigan.[9] In that year, Jean-Baptiste Talon, the first Intendant (administrator) of New France, having heard of reports of a great river to the West and hoping it would be the long-sought "Northwest Passage" to the Pacific Ocean, ordered a reconnaissance mission to find and explore this river. In May of that year the group, consisting of Louis Jolliet, Father Jacques Marquette, and five voyageurs set out on their voyage of discovery.[10]

Accordingly, on The 17th day of may, 1673, we started from the Mission of st. Ignace at Michilimakinac where I Then was. The Joy that we felt at being selected for This Expedition animated our Courage, and rendered the labor of paddling from morning to night agreeable to us.

— Marquette

The explorers found the Mississippi River, explored it,[10] and then returned to Michilimakinac by a different route on the advice of Native Americans they had encountered along the way, who told them that there was a better way to return to Lake Michigan. Travelling by stages up the Illinois River to the Des Plaines River, in September 1673 members of the Caskaskia, a tribe of the Illinois Confederation, led Jolliet and Marquette to the western end of what became known as the Chicago Portage.[10]

During the 18th century, the Chicago Portage was one of the most strategic locations in the interior of the North American continent for the French. In particular, it provided an easy connection between the French cities of Montreal and New Orleans. An indication of the importance of portages that potentially could make this connection is shown in early maps of the region. For example, this French map of the western regions of New France, published 1755, shows the “R.(iviere) et Port de Checageu” (River and Port of Checageu), the “Checageu River”, and the “Portage des Chenes” (the portage of oak trees), the name the French originally attached to the Portage.[11]

Crossing the portage

[edit]

If water level in the portage was high enough to allow passage by canoe for most of the way, passage across the portage was relatively easy. Accounts from soldiers stationed at Fort Dearborn, at the mouth of the Chicago River, describe a passage from west to east. Starting at the west end of the portage at the Des Plaines River they paddled east through Portage Creek and through the marsh that would later be known as Mud Lake. At the east end of the marsh they portaged their boats, equipment, and supplies over a low rise of land that was the St Lawrence River continental divide. They then entered the South Branch of the Chicago River, and paddled north to the Fort.[12]

If water levels in the portage were low, passage was difficult, in part due to the soft or waterlogged ground. In 1818 Gurdon Hubbard, then 16 years old and traveling with a “brigade” of voyageurs as an indentured clerk, crossed the Portage from East to West and left an account in his memoirs.[13][14]

They had traveled down to the Portage from Mackinac Island in bateaux, heavy flat-bottomed boats. They traveled down the South Branch of the Chicago River and pulled their boats over the St Lawrence Continental Divide into Mud Lake where the water was deep enough to float them. Then …

Other members of the crew carried the boats’ cargo, across the seven-mile-long land trail to the Des Plaines River. Because of his status as clerk of the expedition, by virtue of his ability to read and write, Hubbard was spared this hard work. He went on to describe the hardships of crossing the Portage in its natural state.[13]

After a hard day of work crossing the portage, the men camped near the river at the west end of the portage. But their discomfort was not yet over, as Hubbard’s account continues.[13]

Development

[edit]

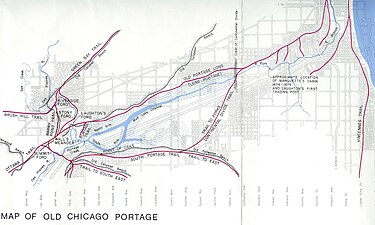

This map of the Portage, superimposed on the map of early Chicago, shows that the most important trails in the region led to the Portage and the several fords near it.

The map also shows the Old Portage Long trail that was used when there was insufficient water in Mud Lake to allow traverse by canoe. This trail extended to the southwest to the early settlement of Ottawa on the Illinois River. Since there was usually sufficient water in the larger Illinois River for canoeing, this “Ottawa Trail” was used in very dry conditions when there was insufficient water in the Des Plaines River.[1]

Wagon roads and today's highways

[edit]As commerce over the portage grew, local entrepreneurs developed services to help travelers using the Portage. One such were the wagon roads that made commerce over the Portage much easier during dry periods. An example is the Ottawa trail that started as a pathway, became a wagon road, and ultimately was paved and became part of US Route 66.[15]

Illinois and Michigan Canal

[edit]The earliest Europeans to cross the Portage saw the potential for a canal dug along the route of the Portage. Louis Jolliet, after his first passage, opined that a canal across “… only a few leagues of prairie…” could link the Great Lakes with the Mississippi Valley.[15]

Eventually, Joliet’s vision came to reality in the form of the Illinois and Michigan (I&M) Canal which opened in 1848.

The birthplace of Chicago, connecting the East with the West

[edit]Recognizing the strategic importance of the Chicago Portage, in 1803 the new country of the United States built Fort Dearborn at the mouth of the Chicago River to guard it.[1]

In 1848 the opening of the I&M canal allowed water transportation from the mouth of St Lawrence River through Chicago to the Mississippi River and the vast ranch and farm lands drained by it. The population of the City tripled in the next six years. The Chicago Portage, established thousands of years before as the link between the two great waterway systems of America, would give birth to Chicago which would go on to become the transportation hub of the US and continue its role as the link between the East and the West.

The official flag of the City of Chicago is a stylized map of the Chicago Portage, with four red stars symbolizing the city and its history, separating two blue stripes symbolizing the two great waters that meet at the city.[16]

Chicago Portage National Historic Site

[edit]The Chicago Portage National Historic Site is a National Historic Site[17] in Lyons, Cook County, Illinois, United States. The site, designated January 3, 1952 as an "affiliated area" of the National Park Service, is owned and administered by the Forest Preserve District of Cook County

Preserved within the park is the western end of the historic Chicago Portage. The site is the only part of the Portage that remains in a natural and protected state more or less as it existed when in use by Native Americans and the Europeans who came after them.[18]

The Des Plaines River today is not the river as it was in, for example, 1673 when Jolliet and Marquette first passed through the Chicago Portage. During the period 1892-1900 the original channel of the river was straightened, cutting off the part that the Jolliet and Marquette party used to reach the west end of the portage.[15] This aerial photo shows the Des Plaines River and the area around the Portage Historic Site as they exist today (2024). The remnants of the old course of the river can be seen as faint collections of water in the middle of the image. The current course of the Des Plaines River flows North to South and is shown just to the left of these remnants.

The second image shows the ancient course of the Des Plaines River overlayed (in blue) on the photo above it to show the river as it was during the centuries of the Portage’s use.[19] Travelers coming from the West would approach from the Southwest, using the old river outlined in blue. Reaching the bend in the river they would either head East into Mud Lake, if there was sufficient water there to permit that option, or stop at the landing, offload their canoes or boats, and carry everything along the Portage trails to reach the South Branch of the Chicago River. The Chicago Portage National Historic Site is outlined in red and the map shows the entrance to Mud Lake and the West End Landing.

Further proof that the original course of the Des Plaines River is as shown comes from the third map, one of many from the Knight and Zeuch study of the Chicago Portage.[19], p 95 This one shows the old course of the Des Plaines River and the bend in the river that marked the western end of the portage.

Further reading

[edit]A History of the Chicago Portage (2021), Benjamin Sells, Northwestern U. Press

The Location of the Chicago Portage Route of the Seventeenth Century: A Paper Read Before the Chicago Historical Society, May 1, 1923

Gallery

[edit]-

Mississippi Valley watershed and Chicago. The Great Lakes-St Lawrence basin is to the north-east (upper-right).

-

Great Lakes Basin and St. Lawrence watershed. The Chicago Portage to the Mississippi Valley is to the south west (lower-left) of Lake Michigan.

-

The Illinois and Michigan Canal breached the water divide in 1848. It was largely replaced by the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal in 1900.

See also

[edit]- Chicago River

- Geography of Chicago

- Valparaiso Moraine

- Lake Chicago

- Saint Lawrence River Divide

- Laurentian Divide

- Eastern Continental Divide

- Stevenson Expressway

- Illinois and Michigan Canal

- Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Solzman, David. "Portage". Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- ^ Alden, William (1902). "Description of the Chicago District from US Geological Survey, Geologic Atlas of the US, Nbr 81;". Transcribed by Ellin Beltz.

- ^ "How Was the Portage Created?". The Chicago Portage.

- ^ Schaetzl, Randall. "Glacial Lakes in Michigan". Michigan State University.

- ^ "What The Glacier Left Behind". The Chicago Portage.

- ^ Vierling, Philip (2001). "Chicago Portage Ledger - Mud Lake". Carnegie Mellon University Libraries (Vol 2, Nbr 1 ed.). p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Sells, Benjamin (2021). A History Of The Chicago Portage. Northwestern University Press.

- ^ Markman, Charles (1991). Chicago before History. Illinois Historic Preservation. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Cordes, Luke (October 28, 2016). "The Trade History of Fort Michilimackinac". Michigan Technological University.

- ^ a b c "Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France". Creighton University. 1889.

- ^ Bellin, Jacques Nicolas (1755). "Partie occidentale de la Nouvelle France ou du Canada". Library of Congress.

- ^ "The Creek, The Portage and the Journey's End". The Chicago Portage.

- ^ a b c "Crossing the Chicago Portage". The Chicago Portage.

- ^ Hubbard, Gurdon (1911). The Autobiography of Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard. Chicago, IL: R. R. Donnelley & Sons.

- ^ a b c "The Chicago Portage - Historical Synopsis". The Chicago Portage.

- ^ "Chicago Facts". Chicago Public Library.

- ^ "CHICAGO PORTAGE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE". Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

- ^ "The Future of The Past". Friends of the Chicago Portage. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ a b Knight, Robert; Zeuch, Lucius Henry (1928). The Location of the Chicago Portage Route of the Seventeenth Century. Chicago Historical Society.