Chautauqua

Chautauqua (/ʃəˈtɔːkwə/ shə-TAW-kwə) is an adult education and social movement in the United States that peaked in popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua brought entertainment and culture for the whole community, with speakers, teachers, musicians, showmen, preachers, and specialists of the day.[1] U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt is often quoted as saying that Chautauqua is "the most American thing in America".[2][3] What he actually said was: "it is a source of positive strength and refreshment of mind and body to come to meet a typical American gathering like this—a gathering that is typically American in that it is typical of America at its best."[4] Several Chautauqua assemblies continue to gather to this day, including the original Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, New York.

History

[edit]

The First Chautauquas

[edit]In 1874, Methodist Episcopal minister John Heyl Vincent and businessman Lewis Miller organized the New York Chautauqua Assembly at a campsite on the shores of Chautauqua Lake in the state of New York.[5] Two years earlier, Vincent, editor of the Sunday School Journal, had begun to train Sunday school teachers in an outdoor summer school format. The gatherings grew in popularity. The organization Vincent and Miller founded later became known as the Chautauqua Institution. Many other independent Chautauquas were developed in a similar manner.[6]

The educational summer camp format proved popular for families and was widely copied by several Chautauquas. Within a decade, "Chautauqua assemblies" (or simply "Chautauquas"), named for the location in New York, sprang up in various North American locations. The Chautauqua movement beginning in the 1870s may be regarded as a successor to the Lyceum movement from the 1840s.[7] As the Chautauquas began to compete for the best performers and lecturers, lyceum bureaus assisted with bookings. Today, Lakeside Chautauqua and the Chautauqua Institution, the two largest Chautauquas, still draw thousands each summer season.

Independent Chautauquas

[edit]Independent Chautauquas (or "daughter Chautauquas") operated at permanent facilities, usually fashioned after the Chautauqua Institute in New York, or at rented venues such as in an amusement park.[8][9] Such Chautauquas were generally built in an attractive semirural location a short distance outside an established town with good rail service. At the Chautauqua movement's height in the 1920s, several hundred of these existed, but their numbers have since dwindled.[10][11]

Circuit Chautauquas

[edit]

"Circuit Chautauquas" (or colloquially, "Tent Chautauquas") were an itinerant manifestation of the Chautauqua movement founded by Keith Vawter (a Redpath Lyceum Bureau manager) and Roy Ellison in 1904.[12] Vawter and Ellison were unsuccessful in their initial attempts to commercialize Chautauqua, but by 1907 they had found a great success in their adaptation of the concept. The program was presented in tents pitched "on a well-drained field near town".[13] After several days, the Chautauqua would fold its tents and move on. The method of organizing a series of touring Chautauquas is attributed to Vawter.[14] Among early Redpath comedians was Boob Brasfield.[15]

Reactions to tent Chautauquas were mixed. In We Called it Culture, Victoria and Robert Case write of the new itinerant Chautauqua:

The credit–or blame–for devising the Frankenstein mechanism which was both to exalt and to destroy Chautauqua, the tent circuit, must be given to two youths of similar temperament, imagination, and a common purpose. That purpose, bluntly, was to "make a million".[16]

Frank Gunsaulus attacked Vawter:

"You're ruining a splendid movement," Gunsaulus roared at Keith Vawter, whom he met at a railroad junction. "You're cheapening Chautauqua, breaking it down, replacing it with something what [sic] will have neither dignity nor permanence."[17]

In Vawter's scheme, each performer or group appeared on a particular day of the program. "First-day" talent would move on to other Chautauquas, followed by the "second-day" performers, and so on, throughout the touring season. By the mid-1920s, when circuit Chautauquas were at their peak, they appeared in over 10,000 communities to audiences of more than 45 million; by about 1940 they had run their course.[18]

The Chautauquan

[edit]The Chautauquan was a magazine founded in 1880 by Theodore L. Flood. First printed in Jamestown, New York, the magazine soon found a home in Meadville, Pennsylvania, where Flood bought a printing shop. It printed articles about Christian history, Sunday school lessons, and lectures from Chautauqua. By the end of the decade, the magazine was printing articles by well-known authors of the day (John Pentland Mahaffy, John Burroughs, Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen), and serial educational material (including courses by William Torrey Harris and Arthur Gilman). Strongly allied with the main organization, it had easy access to popular authors ("the big fish in the intellectual sea", according to Frank Luther Mott), but Flood was wary of making his magazine too dry for popular taste, and sought variety. By 1889 the magazine changed course radically and dropped the serials that were Chautauqua's required reading, expanding with articles on history, biography, travel, politics, and literature. One section had editorial articles from national newspapers; another was the "Woman's Council Table", which excerpted articles often by famous women writers, though all this material remained required reading for the Chautauqua program. Contemporary publications regarded the magazine highly, and Mott writes, "its range of topics was indeed remarkable, and its list of contributors impressive". Flood stopped editing the magazine in 1899, and journalist Frank Chapin Bay, schooled by Chautauqua, took over; the magazine became less a general magazine and more the official organ of the organization.[19]

Lectures

[edit]

Lectures were the mainstay of the Chautauqua. Until 1917, they dominated the circuit Chautauqua programs. The reform speech and the inspirational talk were the two main types of lecture until 1913.[20] Later topics included current events, travel, and stories, often with a comedic twist.[citation needed]

The most famous speech

[edit]The most prolific speaker (often booked in the same venues with three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan) was Russell Conwell, who delivered his famous "Acres of Diamonds" speech 5,000 times to audiences on the Chautauqua and Lyceum circuits, which had this theme:[20]

Get rich, young man, for money is power and power ought to be in the hands of good people. I say you have no right to be poor.[21]

Other speakers

[edit]Maud Ballington Booth, the "Little Mother of the Prisons", was another popular circuit performer. Her descriptions of prison life moved her audiences to tears and roused them to reform. Jane Addams spoke on social problems and her work at Hull House. Helen Potter was another notable Chautauqua performer. She performed a variety of roles, including men and women. Gentile writes: "Potter's choice of subjects is noteworthy for its variety and for the fact that she was credible in her impersonations of men as well as of women. In retrospect, Potter's impersonations are of special interest as examples of the kind of recycling or refertilization of inspiration that occurs throughout the history of the one-person show."[22] On a lighter note, author Opie Read's stories and homespun philosophy endeared him to audiences. Other well-known speakers and lecturers at Chautauqua events of various forms included U.S. Representative Champ Clark, Missouri Governor Herbert S. Hadley, and Wisconsin Governor "Fighting Bob" La Follette.[20]

Religious expression

[edit]Christian instruction, preaching, and worship were a big part of the Chautauqua experience. Although the movement was founded by Methodists, nondenominationalism was a Chautauqua principle from the beginning, and prominent Catholics like Catherine Doherty took part. In 1892, Lutheran theologian Theodore Emanuel Schmauk was one of the organizers of the Pennsylvania Chautauqua.[citation needed]

Early religious expression in Chautauqua was usually of a general nature, comparable to the later Moral Re-Armament movement. In the first half of the 20th century, fundamentalism was the subject of an increasing number of Chautauqua sermons and lectures. But the great number of Chautauquas, as well as the absence of any central authority over them, meant that religious patterns varied greatly among them. Some were so religiously oriented that they were essentially church camps, while more secular Chautauquas resembled summer school and competed with vaudeville in theaters and circus tent shows with their animal acts and trapeze acrobats.

One example, Lakeside Chautauqua, is privately owned but affiliated with the United Methodist Church. In contrast, the Colorado Chautauqua is entirely nondenominational and mostly secular.[23]

Competition with vaudeville

[edit]In the 1890s, both Chautauqua and vaudeville were gaining popularity and establishing themselves as important forms of entertainment. While Chautauqua had its roots in Sunday school and valued morality and education highly, vaudeville grew out of minstrel shows, variety acts, and crude humor, and so the two movements found themselves at odds. Chautauqua was considered wholesome family entertainment and appealed to middle classes and people who considered themselves respectable or aspired to respectability. Vaudeville, on the other hand, was widely considered vulgar babbitry, and appealed to working-class men. There was a stark distinction between the two, and they generally did not share performers or audiences.[24][25]

At the turn of the 20th century, vaudeville managers began a push for more "refinement", as well as a loosening of Victorian-era morals from the Chautauqua side. Over time, as vaudeville became more respectable, Chautauqua became more permissive in what it considered acceptable acts. The boundaries between the two began to blur.[26]

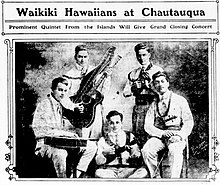

Music

[edit]

Music was important to Chautauqua, with band music in particular demand. John Philip Sousa protégé Bohumir Kryl's Bohemian Band was frequently seen on the circuit. One of the numbers Kryl featured was the "Anvil Chorus" from Il Trovatore, with four husky timpanists in leather aprons hammering on anvils shooting sparks (enhanced through special effects) across the darkened stage. Spirituals were also popular. White audiences appreciated seeing African-Americans performing something other than minstrelsy. Other musical features of the Chautauqua included groups like the Jubilee Singers, who sang a mix of spirituals and popular tunes, and singers and instrumental groups like American Quartette, who played popular music, ballads, and songs from the "old country". Entertainers on the Chautauqua circuit such as Charles Ross Taggart, billed as "The Man From Vermont" and "The Old Country Fiddler", played violin, sang, performed ventriloquism and comedy, and told tall tales about life in rural New England.[citation needed]

Opera became a part of the Chautauqua experience in 1926, when the American Opera Company, an outgrowth of the Eastman School of Music, began touring the country. Under the direction of Russian tenor Vladimir Rosing, the AOC presented five operas in one week at the Chautauqua Amphitheater.[27] By 1929, a permanent Chautauqua Opera company had been established.[28]

Political context

[edit]Chautauquas can be viewed in the context of the populist ferment of the late 19th century. Manifestos such as the "Populist Party Platform"[29] voiced disdain for political corruption and championed the plight of the common people in the face of the rich and powerful. Other favorite political reform topics in Chautauqua lectures included temperance (even prohibition), women's suffrage, and child labor laws.[citation needed]

But the Chautauqua movement usually avoided taking political stands as such, instead inviting public officials of all major political parties to lecture, assuring a balanced program for the members of the assembly. For example, during the 1936 season at the Chautauqua Institution, in anticipation of that year's presidential election, visitors heard addresses by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Republican nominee Alf Landon, and two third-party candidates.[30]

Typical Chautauqua circuit

[edit]A route taken by a troupe of Chautauqua entertainers, the May Valentine Opera Company, which presented Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado during its 1925 "Summer Season", began on March 26 in Abbeville, Louisiana, and ended on September 6 in Sidney, Montana.[31]

In popular culture

[edit]The Chautauqua style of teaching is a recurring motif in Robert M. Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.[2]

The Trouble with Girls, a 1969 film starring Elvis Presley, was based on the 1960 novel Chautauqua by Day Keene and Dwight Vincent Babcock.[32]

See also

[edit]- Chautauqua Circle

- Chautauqua Girl, a Canadian telefilm that takes place in the context of the 1920s Chautauqua movement

- Lecture circuit

- Lyceum

- Lyceum Movement

- Oregon Lyceum

- TED Talks

References

[edit]- ^ Traveling Culture: Circuit Chautauqua in the Twentieth Century – Collection Connections – For Teachers (Library of Congress) Archived May 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Loc.gov. Retrieved on 2011-03-28.

- ^ a b Pirsig, Robert M. (1999). Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values. New York: Quill. ISBN 0688171664. 25th Anniversary Edition.

- ^ Ables, Kelsey (13 August 2022). "What is Chautauqua? The site of the Rushdie attack has a long history". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Cooper, George (2015-07-25). "The Daily Record: Roosevelt lauds Chautauqua as 'typical of America at its best'". The Chautauquan Daily. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 19.

- ^ "History of Chautauqua in Florida". Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "Lyceum movement | American education | Britannica".

- ^ The Chautauquan. M. Bailey, Publisher. 1905.

- ^ Services, DNC Web. "amusement-parks-gallery-1 - RockfordReminisce.com". RockfordReminisce.com. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ Parlette, Ralph Albert (1922). The Lyceum Magazine.

- ^ Ohio, Lakeside (2019-03-17). "The Chautauqua Movement". Lakeside Ohio. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- ^ Gentile, John S. (1989). Cast of One: One-Person Shows from the Chautauqua Platform to the Broadway Stage. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-252-01584-3.

- ^ Galey, Mary (1998-04-01). The Grand Assembly. Winlock Galey. ISBN 9781890461041.

- ^ Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (1921): The World's Work ...: A History of Our Time Vol. XLII. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- ^ "Uncle Cyp & Aunt Sap". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- ^ Case, Victoria (28 March 2007). We Called It Culture - The Story Of Chautauqua. Chapman Press. p. 284. ISBN 9781406775440. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Case, Victoria; Case, Robert O. (1948). We Called it Culture: The Story of Chautauqua. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 51, 73.

- ^ "What Was Chautauqua". www.gearhartseitz.com. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- ^ Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines, 1865-1885. Vol. 3. The Belknap Press. pp. 544–47. ISBN 9780674395527.

- ^ a b c Tapia, John E. (1997). Circuit chautauqua: from rural education to popular entertainment in early twentieth century America. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 53. ISBN 0-7864-0213-X. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ Smith Zimmermann Heritage Museum: Chautauqua History Archived October 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gentile, John (1989). Cast of One: One-person Shows from the Chautauqua Platform to the Broadway Stage. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 43.

- ^ Lehndorff, John (2023-07-06). "Hearing history". Boulder Weekly. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ ""The Fourth American Institution"".

- ^ Hibschman, Harry (1928). "Chautauqua "Pro" and "Contra"". The North American Review. 225 (843): 597–605. JSTOR 25110497.

- ^ Gentile, John, S. (1989). Cast of One: One-Person Shows from the Chautauqua Platform to the Broadway Stage. University of Illinois Press. pp. 47–51. ISBN 0-252-01584-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chautauqua Opera – History. Opera.ciweb.org. Retrieved on 2011-03-28 from http://opera.ciweb.org/history/.

- ^ "The Chautauqua Opera Company". Chautauqua Opera Company.

- ^ People's Party Platform, Omaha Morning World-Herald, 5 July 1892

- ^ "Chautauqua! Elling House hosts first Chautauqua of 2019 | The Madisonian". www.madisoniannews.com. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- ^ May Valentine Opera Co. in Gilbert and Sullivan's "The Mikado" Archived January 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine from a University of Iowa Library website that's part of American Memory archives

- ^ Worth, Fred L.; Tamerius, Steve D. (1992). Elvis: His Life from A to Z. New York: Wings Books. pp. 229–301.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hurlbut, Jesse Lyman (1921): The Story of Chautauqua. New York: G.P. Putman's Sons.

- What was Chautauqua? University of Iowa Libraries, accessed: 2006-03-18.

- Galey, Mary (1981): The Grand Assembly: The Story of Life at the Colorado Chautauqua. Boulder, Colorado: First Flatiron Press, ISBN 0-9606706-0-2.

- Gentile, John S (1989): Cast of One: One-Person Shows from the Chautauqua Platform to the Broadway Stage. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01584-3.

- Gould, Joseph Edward (1961): "The Chautauqua Movement". Albany, New York. State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-87395-003-8.

- Pettem, Silvia (1998): Chautauqua Centennial, a Hundred Years of Programs. http://www.silviapettem.com/books.html

- Rieser, Andrew (2003): The Chautauqua Moment: Protestants, Progressives, and the Culture of Modern Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231126425.

- Strother, French (September 1912). "The Great American Forum: Chautauqua and the Chautauquas in Summer and the Lyceum In Winter". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXIV: 551–564. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- Merkel, Diane on behalf of the Walton County Heritage Association (2008): Images of America DeFuniak Springs. Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-5407-3.

External links

[edit]- Chautauqua Institution Archived 2020-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- The Great Lecture Library

- Traveling Culture: Circuit Chautauqua in the Twentieth Century

- Colorado Chautauqua, Boulder,CO

- Greenville Chautauqua Society

- New Piasa Chautauqua, Chautauqua, IL

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Chautauqua

- Program catalog, 1905 Chautauqua, Rockford, IL