The African Queen (film)

| The African Queen | |

|---|---|

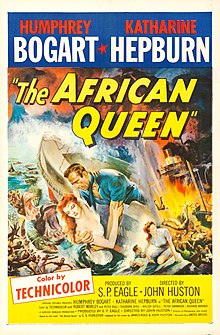

US theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Huston |

| Screenplay by | John Huston James Agee Peter Viertel John Collier |

| Based on | The African Queen 1935 novel by C. S. Forester |

| Produced by | Sam Spiegel John Woolf (uncredited) |

| Starring | Humphrey Bogart Katharine Hepburn Robert Morley |

| Cinematography | Jack Cardiff |

| Edited by | Ralph Kemplen |

| Music by | Allan Gray |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Languages | English German Swahili |

| Budget | $1 million[3] |

| Box office | $10.75 million[4] |

The African Queen is a 1951 adventure film adapted from the 1935 novel of the same name by C. S. Forester.[5] The film was directed by John Huston and produced by Sam Spiegel and John Woolf.[6] The screenplay was adapted by James Agee, John Huston, John Collier and Peter Viertel. It was photographed in Technicolor by Jack Cardiff and has a music score by Allan Gray. The film stars Humphrey Bogart (who won the Academy Award for Best Actor, his only Oscar) and Katharine Hepburn with Robert Morley, Peter Bull, Walter Gotell, Richard Marner and Theodore Bikel.[7]

The African Queen was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1994, and the Library of Congress deemed it "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant."[8][9]

Plot

[edit]Samuel Sayer and his sister Rose are English Methodist missionaries in German East Africa in August 1914. Their mail and supplies are delivered by a small steamboat named the African Queen, helmed by the rough-and-ready Canadian mechanic Charlie Allnut, whose coarse behavior they stiffly tolerate.

When Charlie warns the Sayers that war has broken out between Germany and Britain, they choose to remain in Kungdu, only to witness German colonial troops burn down the village and herd the villagers away to be pressed into service. When Samuel protests, he is struck by a soldier and soon becomes delirious with fever, dying shortly afterward. Charlie helps Rose bury her brother and they escape in the African Queen.

Charlie mentions to Rose that the British are unable to attack the Germans because of the presence of a large gunboat, the Königin Luise, patrolling a large lake downriver. Rose comes up with a plan to convert the African Queen into a torpedo boat and sink the Königin Luise. After some persuasion, Charlie goes along with the plan.

Charlie encourages Rose to navigate the river by rudder while he tends the engine, and she is emboldened after they pass the first set of rapids with minimal flooding in the boat. When they pass the German fortress, the soldiers begin shooting at them, damaging the boiler. Charlie manages to reattach a pressure hose just as they are about to enter the second set of rapids. The boat rolls and pitches as it goes down the rapids, leading to more severe flooding on the deck. While celebrating their success, Charlie and Rose find themselves in an embrace and kiss. The third set of rapids damages the boat's propeller shaft. They rig up a primitive forge on shore and Charlie straightens the shaft and welds a new blade onto the propeller, allowing the two to set off again.

All appears lost when the boat becomes mired in the mud and dense reeds near the mouth of the river. With no supplies left and short of potable water, Rose and a feverish Charlie pass out, both accepting that they will soon die. Rose says a quiet prayer. As they sleep, torrential rains raise the river's level and float the African Queen into the lake.

Over the next two days, Charlie and Rose prepare for their attack. The Königin Luise returns and Charlie and Rose steam the African Queen out onto the lake in darkness, intending to set her on a collision course. A strong storm strikes, causing water to pour into the African Queen through the torpedo holes. Eventually the boat capsizes, throwing Charlie and Rose into the water. Charlie loses sight of Rose in the storm.

Charlie is captured and taken aboard the Königin Luise, where he is interrogated by German officers. Believing that Rose has drowned, he makes no attempt to defend himself against accusations of spying and the German captain sentences him to death by hanging. Rose is brought aboard the ship just after Charlie's sentence is pronounced. The captain questions her, and Rose proudly confesses the plot to sink the Königin Luise, deciding that they have nothing to lose. The captain sentences her to be executed with Charlie, both as British spies. Charlie asks the German captain to marry them before they are executed. The captain agrees, and after conducting the briefest of marriage ceremonies, is about to carry out the execution when the Königin Luise is rocked by a series of explosions, quickly capsizing. The ship has struck the overturned submerged hull of the African Queen and detonated the torpedoes. The newly married couple is able to escape the sinking ship and swim to safety together.

Cast

[edit]- Humphrey Bogart as Charlie Allnut

- Katharine Hepburn as Rose Sayer

- Robert Morley as Reverend Samuel Sayer, "The Brother"

- Peter Bull as the Captain of the Königin Luise

- Theodore Bikel as the First Officer of the Königin Luise

- Walter Gotell as the Second Officer of the Königin Luise

- Peter Swanwick as the First Officer of Fort Shona

- Richard Marner as the Second Officer of Fort Shona

- Gerald Onn as Petty Officer of the Königin Luise (uncredited)[10]

Production

[edit]

Production censors objected to several aspects of the original script, such as the two unmarried characters cohabiting the boat (as in the book), and some changes were made before the film was completed.[11] Another change followed the casting of Bogart; his character's lines in the original screenplay were rendered with a thick Cockney dialect, but the script had to be completely rewritten because he was unwilling to attempt the accent. The rewrite made the character Canadian.

The film was partially financed by John and James Woolf of Romulus Films, a British company. Michael Balcon, an advisor to the National Film Finance Corporation, advised the NFFC to refuse a loan to the Woolfs unless the film starred his former Ealing Studios actors John McCallum and Googie Withers rather than Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, whom the Woolfs wanted. The Woolfs persuaded NFFC chairman Lord Reith to overrule Balcon, and the film went ahead.[12] The Woolfs provided £250,000 and were so pleased with the completed film that they convinced John Huston to direct their next picture, Moulin Rouge (1952).[13]

Much of the film was shot in Lake Albert, Uganda and the in Belgian Congo in Africa. This was rather novel for the time, especially for a Technicolor picture that used large, cumbersome "Three-Strip" cameras. The cast and crew endured sickness and spartan living conditions during their time on location. In the early scene in which Hepburn plays an organ in the church, a bucket was placed off-camera in which she could vomit between takes because she was sick. Bogart later bragged that he and Huston were the only members of the cast and crew who escaped illness, which he credited to having drunk whiskey on location rather than the local water.[14][15]

About half of the film was shot in the UK. The scenes in which Bogart and Hepburn are seen in the water were all shot in studio tanks at Worton Hall Studios in Isleworth, near London. These scenes were considered too dangerous to shoot in Africa. All of the foreground plates for the process shots were also filmed in studio.[16] A myth has grown that the scenes in the reed-filled riverbank were filmed in Dalyan, Turkey,[17] but in her book about the filming, Hepburn stated: "We were about to head... back to Entebbe but John [Huston] wanted to get shots of Bogie and me in the miles of high reeds before we come out into the lake...". The sequence was shot on location in Africa and at the London studios. The shots of the German-occupied Fort Shona were all filmed at Worton Hall, where a fortress set was constructed from tubular scaffolding and covered with plaster.[18]

Scenes on the boat were filmed using a large raft with a mockup of the boat on top. Sections of the boat set could be removed to make room for the large Technicolor camera. This proved hazardous on one occasion when the boat's boiler, a heavy copper replica, almost fell on Hepburn. It was not secured to the deck because it also had to be moved to accommodate the camera. The small steamboat used to depict the African Queen was built in 1912 in Britain for service in Africa. At one time it was owned by actor Fess Parker.[19] The boat was restored in April 2012 and is now on display as a tourist attraction in Key Largo, Florida.[20][21]

Because of the dangers involved with shooting the rapids scenes, a small-scale model was used in the studio tank in London. The vessel used to portray the German gunboat Königin Luise was the steam tug Buganda, owned and operated on Lake Victoria by the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation. Although fictional, the Königin Luise was inspired by the World War I vessel Graf Goetzen (also known as Graf von Goetzen),[22] which operated on Lake Tanganyika until she was scuttled in 1916 during the Battle for Lake Tanganyika. The British refloated the Graf Goetzen in 1924 and placed her in service on Lake Tanganyika in 1927 as the passenger ferry MV Liemba and she is still operating with continuing maintenance agreed in 2023.[23]

The name Königin Luise was taken from a German steam ferry SS Königin Luise (1913) that operated from Hamburg before being taken over by the Kaiserliche Marine on the outbreak of World War I. She was used as an auxiliary minelayer off Harwich before being sunk on 5 August 1914 by the cruiser HMS Amphion.[24]

A persistent rumour holds that London's population of feral ring-necked parakeets originated from birds that escaped or were released during filming of The African Queen.[25]

Premiere

[edit]The African Queen opened on December 26, 1951, at the Fox Wilshire Theatre in Beverly Hills[2] in time to qualify for the 24th Academy Awards. The film opened in New York City on February 20, 1952, at the Capitol Theatre.[26]

Reception and box office

[edit]Contemporary critical reviews were mostly positive. Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "should impress for its novelty both in casting and scenically," and found the ending "rather contrived and even incredible, but melodramatic enough, with almost a western accent, to be popularly effective."[27] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "a slick job of movie hoodwinking with a thoroughly implausible romance, set in a frame of wild adventure that is as whopping as its tale of off-beat love ... This is not noted with disfavor." Crowther added that "Mr. Huston merits credit for putting this fantastic tale on a level of sly, polite kidding and generally keeping it there, while going about the happy business of engineering excitement and visual thrills."[26]

Variety called The African Queen "an engrossing motion picture ... Performance-wise, Bogart has never been seen to better advantage. Nor has he ever had a more knowing, talented film partner than Miss Hepburn."[28] John McCarten of The New Yorker declared that "Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart come up with a couple of remarkable performances, and it's fortunate that they do, for the movie concentrates on them so single-mindedly that any conspicuous uncertainty in their acting would have left the whole thing high and dry."[29] Richard L. Coe wrote in The Washington Post that "Huston has tried a risky trick and most of the time pulls it off in delicious style. And from both his stars he has drawn performances which have rightly been nominated for those Academy Awards on the [20th]."[30]

Harrison's Reports printed a negative review, writing that the film "has its moments of comedy and excitement, but on the whole the dialogue is childish, the action silly, and the story bereft of human appeal. The characters act as childishly as they talk, and discriminating picture-goers will, no doubt, laugh at them. There is nothing romantic about either Katharine Hepburn or Humphrey Bogart, for both look bedraggled throughout."[31] The Monthly Film Bulletin was also negative, writing: "Huston seems to have been aiming at a measured, quiet, almost digressive tempo, but the material does not support it, and would have benefited by the incisiveness his previous films have shown. In spite of Hepburn's wonderful playing, and some engaging scenes, the film must be accounted a misfire."[32]

The film earned an estimated £256,267 at UK cinemas in 1952,[33] making it the 11th-most-popular film of the year.[34] It earned an estimated $4 million in North American theatrical rentals and $6 million worldwide.[35][36]

On review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes the film has a 96% rating based on 47 reviews, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Perfectly cast, smartly written, and beautifully filmed, The African Queen remains thrilling, funny, and effortlessly absorbing even after more than half a century's worth of adventure movies borrowing liberally from its creative DNA."[37] On Metacritic it has a score of 91% based on reviews from 15 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[38]

Differences from the novel

[edit]In 1935, when the novella The African Queen by C. S. Forester was published, many British people believed that World War I was a grievous mistake that could have been avoided. In the novella, the Germans are the antagonists, not the villains, and are depicted as noble and chivalrous opponents of the British, who are likewise equally noble and honorable.[39] The overall message of the novella was that the war was a tragedy in which decent people killed one another for unfathomable reasons and that both sides suffered equally.[39] The British historian Antony Barker wrote in the book there is a strong sense of the shared suffering of the European characters in Africa during the war including the Germans who are presented as having only a "limited responsibility" for the war.[40] By contrast, when the film version of The African Queen came out in 1951, memories of the Second World War were still fresh and the German characters were far more villainous and disagreeable than in the novella.[41] Unlike the memory of the First World War, the Second World War was remembered as a crusade against evil, which influenced the script of The African Queen.[41] In the novella, the Germans capture Rose and Charlie, but release them in a magnanimous gesture, unaware of the failed plot.[39] Likewise, in the film they capture Rose and Charlie, but are on the verge of hanging them when the Königin Luise is sunk by the wreck of The African Queen.[41]

In the novella, Charlie and Rose fail in their attempt to sink the Königin Luise as the message in the book is: "What appears to be an impossible mission for a private citizen is shown to be just that--it remains a job best left for the professionals".[39] The Königin Luise is instead sunk in a lake battle by a Royal Navy gunboat as Rose and Charlie watch from the shore.[39] The film presented the efforts of Charlie and Rose in a more favorable light as their struggle to bring The African Queen to the lake does causes the sinking of the Königin Luise, and the Royal Navy gunboat does not appear in the film.[41] In the novella, the character of Charlie was British; in the film, he becomes Canadian to accommodate Bogart's American accent.[41] In 1915, there was a successful expedition commanded by Geoffrey Spicer-Simson where the British dragged two Royal Navy gunboats across the African wilderness to Lake Tanganyika to challenge German naval mastery of the lake, which served as the inspiration for the novella.[39] C. S. Forester, the author of The African Queen did not focus on the story of the real life expedition, which he incorporated into his novella as the Royal Navy gunboat in the book is clearly supposed to be one of the two real life gunboats, largely because of the tremendous suffering endured by the African porters who had to drag the two gunboats across the wilderness, an aspect of the expedition that Forester did not wish to dwell upon.[39]

During the campaign in East Africa, the German forces were quite ruthless in forcibly conscripting Africans to work as porters; seizing animals and food for themselves; and in carrying out a scorched earth strategy meant to deny the pursuing British forces the use of the countryside.[40] Barker wrote that the heroic way that the crew of the Königin Luise go down fighting in the book "cancelled" out the brutal behavior of the German forces earlier while in the film the sinking of the Königin Luise is the just punishment of the German characters.[39] Both the book and the film accurately depict the scorched earth tactics of the German Schutztruppe, which had a devastating effect on the African peoples as thousands of Africans starved to death as a result of the destruction of crops and farm animals.[42] However, the focus in both the film and the book are on the white characters and both the film and book treats the Africans as mere extras in the story.[40] Despite the fact that both the book and the novella are set in the Great Lakes region of Africa, there are no important African characters in either the book or the film.[40] Both the book and the film present Africa as a exotic and dangerous locale where white people have adventures and romances, with the Africans themselves just in the background.[40]

Both the book and the film treat Africa as a place where it is possible to find happiness in a way that would be impossible in Europe. In both the book and the film, Rose is a prim, proper missionary from a middle class English family who is dominated by her bossy older brother Samuel, and it is during the voyage of the African Queen that she finds romance and happiness with Charlie along with the courage to assert herself.[40] In the book, Charlie is a coarse and somewhat disreputable working class Cockney who marries a middle class woman that he would be unlikely to marry in England.[39] The film changes Charlie into a Canadian, but has the same message that a working class man is able to marry a middle class woman that he would be unlikely to marry in a place other than Africa.[41] In the book, it is strongly implied that Rose and Charlie are engaged in a sexual relationship before marriage, an aspect of the book that was toned down in the film because of the Hayes Code, which forbade any depiction of a pre-marital sexual relationship. Unlike the book which was a straight adventure story, the film borrows much from American romantic comedies of the 1930s-1940s which portray a "battle of the sexes" that ends with a man and a woman finding love on the basis of "equality and symmetry".[43] The book is set in a thinly disguised version of Lake Tanganyika, on whose eastern shores was the colony of German East Africa (modern Tanzania), but the parts of the film shot on location were filmed in the Belgian Congo (modern Democratic Republic of the Congo) because director Huston had heard that the Belgian Congo was better for hunting elephants.[44]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Director | John Huston | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Humphrey Bogart | Won | |

| Best Actress | Katharine Hepburn | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | James Agee and John Huston | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Foreign Actor | Humphrey Bogart | Nominated | |

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Inducted | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | John Huston | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Katharine Hepburn | Nominated | |

| Online Film & Television Association Awards | Hall of Fame – Motion Picture | Won | |

Others

[edit]American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #17

- 2002 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – #14

- 2006 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – #48

- 2007 – AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #65

AFI has also honored both Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn as the greatest American screen legends.

Subsequent releases

[edit]The film was released on Region 2 DVD in the United Kingdom, Germany and Scandinavia. The British DVD includes a theatrical trailer and an audio commentary by cinematographer Jack Cardiff in which he details many of the hardships and challenges involved in filming in Africa.

Prior to 2010, the film had been released in the United States on VHS video, LaserDisc and as a Region 1 DVD.

2009 digital restoration

[edit]In 2009, Paramount Pictures (the current owner of the film's American rights) completed restoration work for Region 1, and a 4K digitally restored version from the original camera negative was issued on DVD and Blu-ray on March 23, 2010. The film was restored with its original mono soundtrack from original UK film elements under the sole supervision of Paramount, and had as an extra a documentary on the film's production, Embracing Chaos: The Making of The African Queen.[45] Romulus Films and international-rights holder ITV Studios were acknowledged in the restoration credits.

ITV released the restoration in Region 2 on June 14, 2010.

Adaptations in other media

[edit]The African Queen was adapted as a one-hour Lux Radio Theater play on December 15, 1952. Bogart reprised his film role and was joined by Greer Garson.[46] This broadcast is included as a bonus CD in the commemorative box-set version of the Paramount DVD.

The March 26, 1962 episode of The Dick Powell Theater, titled Safari, was based on the story, with James Coburn and Glynis Johns in the lead roles.

A 1977 television film continued the adventures of Charlie and Rose, with Warren Oates and Mariette Hartley in the lead roles. Though intended as the pilot for a series, it was not picked up. An elliptic commentary on the making of The African Queen can be found in the 1990 film White Hunter Black Heart, directed by Clint Eastwood.

The African Queen partially inspired the Jungle Cruise attraction at Disneyland. Imagineer Harper Goff referenced the film frequently in his ideas, and his designs for the ride vehicles were inspired by the steamer used in the film.[47]

The African Queen

[edit]One of the two boats used as the African Queen is actually the 35-foot (10 m) L.S. Livingston, which had been a working diesel boat for 40 years; the steam engine was a prop and the real diesel engine was hidden under stacked crates of gin and other cargo. Florida attorney and Humphrey Bogart enthusiast Jim Hendricks Sr. purchased the boat in 1982 in Key Largo, Florida. After falling into a state of disrepair following Hendricks' 2001 death, the ship was discovered rusting in a Florida marina in 2012 by Suzanne Holmquist and her engineer husband Lance. The couple repaired and refurbished the ailing ship and made it available to tourists and film enthusiasts, providing cruises around the Florida Keys.[48]

References

[edit]Specific

[edit]- ^ "Company Information". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "The African Queen (advertisement)". Los Angeles Times: Part III, p. 8. December 23, 1951.

First world showing – Wednesday, December 26

- ^ Rudy Behlmer, Behind the Scenes, Samuel French, 1990 p. 239

- ^ Box Office Information for The African Queen. The Numbers. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "The African Queen Let's Repatriate(1951)". Reel Classics. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Spiegel was billed as "S.P. Eagle".

- ^ "'The African Queen' – Bogart, Hepburn and the Little Boat That Could". About.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "25 Films Added to National Registry". The New York Times. 1994-11-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ McCarty, Clifford (1965). Bogey: The Films of Humphrey Bogart. Cadillac. p. 161.

- ^ "University of Virginia Library Online Exhibits – CENSORED: Wielding the Red Pen". virginia.edu.

- ^ Sue Harper & Vincent Porter, British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference, OUP, 2007, p.12

- ^ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 46

- ^ Web Designer Express and Web Design Enterprise. "History of the African Queen". The African Queen.

- ^ Cosgrove, Ben. "Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn Filming 'The African Queen,' 1951". Time. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013.

- ^ Embracing Chaos: Making ‘The African Queen' a documentary film

- ^ Light Sword Of The Protector (20 February 1952). "The African Queen (1951)". IMDb.

- ^ Behlmer, Rudy (1982). America's Favorite Movies: Behind the Scenes. F. Ungar Publishing Company. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8044-2036-5. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "MichaelBarrier.com -- Interviews: Fess Parker". michaelbarrier.com.

- ^ "African Queen boat to be restored". BBC News. December 9, 2011.

- ^ "The African Queen sets sail again". CBS News. April 13, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "How Sh48 billion contract will boost Tanganyika, Victoria transport", The Citizen, 23 November 2023

- ^ Details on the Königin Luise

- ^ "Nature Studies: London's beautiful parakeets have a new enemy to deal with". Independent.co.uk. 8 June 2015.

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (February 21, 1951). "' The African Queen,' Starring Humphrey Bogart, Katharine Hepburn, at the Capitol". The New York Times: 24.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (December 27, 1951). "Star Duo in Unique Joust with Jungle". Los Angeles Times: B6.

- ^ "The African Queen". Variety. December 26, 1951. p. 6.

- ^ McCarten, John (February 23, 1952). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 85.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (March 8, 1952). "Hepburn-Bogart Team Is A Honey". The Washington Post. p. B5.

- ^ "'The African Queen' with Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn". Harrison's Reports: 207. December 29, 1951.

- ^ "The African Queen". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 19 (217): 15. February 1952.

- ^ Vincent Porter, 'The Robert Clark Account', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol 20 No 4, 2000 p495

- ^ "Comedian Tops Film Poll". The Sunday Herald. Sydney. 28 December 1952. p. 4. Retrieved 9 July 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1952". Variety. 7 January 1953. p. 61.

- ^ Arneel, Gene (June 29, 1960). "Huston: 'Me For Li'l Budgets'". Variety. p. 19. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "The African Queen (1951)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "The African Queen". Metacritic. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barker 2017, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f Barker 2017, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d e f Barker 2017, p. 235.

- ^ Barker 2017, p. 221 & 230.

- ^ Echart 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Barker 2017, p. 230 & 235-236.

- ^ Chaney, Jen (March 26, 2010). "'The African Queen' new on DVD after more than 50 years". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (December 14, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. p. 54.

- ^ The Imagineers (1996). Walt Disney Imagineering – A Behind the Dreams Look at Making the Magic Real. Disney Editions. p. 112.

- ^ Macguire, Eoghan (May 2, 2012). "Humphrey Bogart's boat 'African Queen' saved from scrapheap". CNN.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barker, Anthony (2017). "African Queens and Ice-Cream Wars: Fictional and Filmic Versions of the East Africa Conflict, 1914-1918". In Pereira, Maria Eugénia; Cortez, Maria Teresa; Pereira, Paulo Alexandre; Martins, Otília (eds.). Personal Narratives, Peripheral Theatres: Essays on the Great War (1914–18). New York: Springer. pp. 221–239. ISBN 9783319668512.

- Echart, Pablo (2010). "Strange, but Close Partners: Huston, Romantic Comedy and The African Queen". In Tony Tracy (ed.). John Huston Essays on a Restless Director. Jefferson: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. pp. 22–33. ISBN 9780786459933.

- Farwell, Byron. The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. 2nd ed. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989.

- Foden, Giles (2005). "Mimi and Toutou Go Forth: The Bizarre Battle of Lake Tanganyika". Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-100984-5

- Hagberg Wright, C.T. German Methods of Development in Africa Journal of the Royal African Society 1.1 (1901): 23–38. Historical. J-Stor. Golden Library, ENMU. 18 April. 2005

- Henderson, William Otto. The German Colonial Empire. Portland: International Specialized Book Services, Inc, 1993.

- Hepburn, Katharine (1987). The Making of the African Queen, or: How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind (Knopf)

- Tibbetts, John C., And James M, Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2005) pp 5–6..

- Werner, A, and R Dilthey. "German and British Colonisation in Africa." Journal of the Royal African Society 4.14 (1905): 238–41. Historical. J-Stor. Golden Library, ENMU. 18 April. 2005.

External links

[edit]- The African Queen at IMDb

- The African Queen at the TCM Movie Database

- The African Queen at AllMovie

- The African Queen at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The African Queen on Lux Radio Theater: December 15, 1952

- The African Queen essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 453-454

- 1951 films

- 1950s adventure drama films

- 1950s romance films

- American adventure drama films

- British adventure drama films

- 1950s English-language films

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on works by C. S. Forester

- Films based on romance novels

- Films directed by John Huston

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films produced by Sam Spiegel

- Films set in 1914

- Films set in Burundi

- Films set in jungles

- Films set in Rwanda

- Films set in Tanzania

- Films set on boats

- Films shot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Turkey

- Films shot in Uganda

- Films shot in the United States

- 1950s German-language films

- Horizon Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by John Huston

- River adventure films

- Swahili-language films

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films

- World War I films based on actual events

- World War I films set in Africa

- World War I naval films

- Films with screenplays by James Agee

- 1951 drama films

- 1950s American films

- 1950s British films

- British World War I films

- English-language romance films

- English-language adventure drama films