Charles Perkins (Aboriginal activist)

Charles Perkins | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

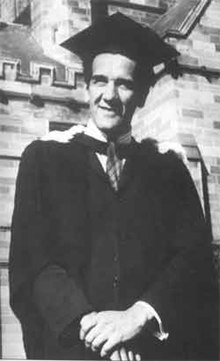

Perkins on graduation day at the University of Sydney in 1966 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 June 1936 Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 19 October 2000 (aged 64) Sydney, New South Wales, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Australian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | Charlie Perkins, Kumantjayi Perkins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Bachelor of Arts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Activism, public service, soccer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Eileen Munchenberg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Hetti, Rachel and Adam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Madeleine Madden (granddaughter) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Charles Nelson Perkins AO, usually known as Charlie Perkins (16 June 1936 – 19 October 2000), was an Aboriginal Australian activist, soccer player and administrator. It is claimed he was the first known Indigenous Australian man to graduate tertiary education. He is known for his instigation and organisation of the 1965 Freedom Ride and his key role in advocating for a "yes" vote in the 1967 Aboriginals referendum. He had a long career as a public servant.

Early life and family

[edit]Perkins was born on 16 June 1936 in the old Alice Springs Telegraph Station[1][2] to Hetty Perkins, originally from nearby Arltunga, and Martin Connelly, originally from Mount Isa, Queensland. His mother was born to a white father and an Arrernte mother, while his father had an Irish father and a Kalkadoon mother. Perkins had one full sibling and nine other half-siblings by his mother, and was also a cousin of artist and soccer player John Moriarty.[citation needed] He was the great-uncle of Pat Turner, and inspired her work to improve the lives of and right to self-determination for Indigenous people.[3]

Between 1952 and 1957, Perkins worked as an apprentice fitter and turner for the British Tube Mills company in Adelaide.[4]

He married Eileen Munchenberg, a descendant of a German Lutheran family, on 23 September 1961 and had two daughters (Hetti and Rachel), and a son (Adam).[4] His granddaughter through Hetti is actress Madeleine Madden.[5]

Education

[edit]Perkins obtained his early schooling at St Mary's Church School in Alice Springs, before moving down to St Francis House for Aboriginal Boys[6] in Semaphore South, a beachside suburb of Adelaide near Port Adelaide, South Australia.[7] There he was treated with kindness, sent to the local school, and met other future Aboriginal leaders and activists, including Gordon Briscoe, John Kundereri Moriarty, Richie Bray, Vince Copley, Malcolm Cooper, and others.[8][9]

He subsequently attended the Metropolitan Business College in Sydney, followed by the University of Sydney, from where he graduated in 1966 with a Bachelor of Arts. He was the first Indigenous man in Australia to graduate from university. While at university he worked part-time for the City of South Sydney cleaning toilets.[6][10]

Public life

[edit]The Freedom Ride

[edit]In 1965 he was one of the key members of the Freedom Ride – a bus tour through New South Wales by activists protesting discrimination against Aboriginal people in small towns in NSW, Australia. This action was inspired by the US Civil Rights Freedom Ride campaign in 1961. The Australian Freedom Ride aimed to expose discrepancies in living, education and health conditions among the Aboriginal population. The tour targeted rural towns such as Walgett, Moree, and Kempsey. They acted to publicise acts of blatant discrimination. This was demonstrated through one of the Freedom Ride activities in Walgett. A local RSL club refused entry to Aboriginal people, including those who were ex-servicemen who participated in the two World Wars. At one stage during the Rides, the protesters' bus was run off the road.[citation needed]

On 20 February 1965, Perkins and his party tried to enter the swimming pool at Moree, where the local council had barred Aboriginal people from swimming since its opening 40 years earlier. They stood at the gate refusing to let anyone else in if they were not let in. In response to this action, the riders faced physical opposition from several hundred local white Australians, including community leaders, and were pelted with eggs and tomatoes. These events were broadcast across Australia, and under pressure from public opinion, the council eventually reversed the ban on Aboriginal swimmers. The Freedom Ride then moved on, but on the way out they were followed by a line of cars, one of which collided with the rear of their bus, forcing them to return to Moree where they found that the council had reneged on their previous decision. The Freedom Riders protested once again, forcing the council to remove the ban once more.[11]

On 6 August 1965, Perkins staged a fake "kidnapping" of 5-year-old Nancy Prasad from under the nose of immigration officials at the Sydney airport for the purpose of highlighting the injustice of her deportation under Australia's "White Australia" immigration policy.[12][13][14] His antic had effect. The newspapers headlined the "kidnapping". Even so, Prasad was taken to the airport again, and deported to Fiji on 7 August 1965.[13]

1967 referendum

[edit]In 1967 a referendum was held on constitutional amendments to allow the inclusion of Aboriginal people in censuses and giving the Parliament of Australia the right to introduce legislation specifically for Aboriginal people. In the lead-up to the referendum Perkins was manager of the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs,[15][16] an organisation that took a key role in advocating a Yes vote.[17] The constitutional amendment passed with a 90.77% majority.[citation needed]

Canberra

[edit]In 1969 Perkins began his career in Commonwealth government public service in the Office of Aboriginal Affairs in Canberra, which became the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) in 1972. In that year he underwent a kidney transplant.[18]

Soon after getting his first job in Canberra, he founded the company Aboriginal Hostels Limited, with the aim of setting up a national network of hostels providing temporary accommodation for Aboriginal people. In 1973, he became the inaugural chair of its board. Joe McGinness and Vince Copley later held management positions in the company, covering different regions.[19]

In 1974 he was suspended on full pay by Barrie Dexter for improper conduct after he called the Liberal–Country Coalition government in Western Australia "biggest racist political parties in this country has ever seen", which came after an earlier altercation with his minister, Labor Senator Jim Cavanagh. During his suspension, he was hailed a hero for disarming a gun-toting man who was threatening two senior officers in the department. However his decision to take a week's leave to sit with the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was the final straw, and he was given leave for a year in 1975.[20]

During his year off, funded by a Literature Board grant, he wrote his autobiography, A Bastard Like Me, and was appointed general secretary of the National Aborigines Consultative Committee,[20] returning to the DAA in 1976.[18] In 1978 he was appointed as a first assistant secretary of the department, and then in 1979 deputy Secretary before resigning in 1980 in order to take up chairmanship of the new Aboriginal Development Commission.[20]

When a Labor government under Bob Hawke was elected in 1983, with Clyde Holding appointed as minister, Perkins was appointed Secretary of the DAA in 1984,[20] holding the position until 1988.[18] Perkins was the first Indigenous person appointed to head an Australian Government department.[21][22]

Throughout his career he was a strident critic of Australian Government policies on Indigenous affairs and was renowned for his fiery comments. Hawke once said of Perkins that he "sometimes found it difficult to observe the constraints usually imposed on permanent heads of departments because he had a burning passion for advancing the interests of his people".[22][23]

He served as chair of the Arrernte Council of Central Australia from 1991 until 2000.[18]

In 1993 Perkins joined the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), and was elected deputy chair in 1994, serving until he resigned in 1995 to become a consultant to the Australian Sports Commission.[20][18]

Public commentary

[edit]On 7 April 2000, Perkins suggested that 'Sydney will burn during the [Sydney 2000] Olympics.' The comment sparked outrage from many different quarters.[24] In May 2000 Perkins declared that the Australian Football League and the Australian Rugby League were racist, suggesting that the AFL "acts in a racist manner at the highest level".[25]

Other roles

[edit]Perkins was secretary of the committee of the Aboriginal Publications Foundation, which published the magazine Identity, in the 1970s.[26]

Soccer career

[edit]Perkins began playing in 1950 with Adelaide team Port Thistle. In 1951 he was selected for a South Australia under 18 representative team. He went on to play for a number of teams in Adelaide including International United (1954–55), Budapest (1956–57) and Fiorentina (1957).

In 1957 he was invited to trial with English first division team Liverpool F.C. Perkins ended up trialling and training with Liverpool's city rival Everton F.C.. While at Everton Perkins had a physical confrontation with the Everton reserve grade manager after being called a "kangaroo bastard". After this incident, Perkins left Everton to move to Wigan where he worked as a coal miner at the Mosley Common Colliery alongside Great Britain rugby league player Terry O'Grady. Perkins played two seasons for leading English amateur team Bishop Auckland F.C. between 1957 and 1959. Perkins in mid-1959 decided to return to Australia after trialling with Manchester United.[4]

On returning to Australia Perkins was appointed captain and coach of Adelaide Croatia. At Croatia he played alongside notable Aboriginal figures Gordon Briscoe and John Moriarty.[27][28]

In 1961 when Perkins moved to Sydney to study at university he played with Pan-Hellenic (later known as Sydney Olympic FC) in the New South Wales State League where he became captain and coach. He later played for Bankstown and retired in 1965.

Following his move to Canberra in 1969, Perkins joined the ANU Soccer Club (later known as the ANU Football Club) as player and coach.[29][30][31][32]

He later served as president of former National Soccer League team Canberra City. In 1987 He was appointed vice-president of the Australian Soccer Federation (a forerunner of the Football Federation Australia) and was the chairman of the Australian Indoor Soccer Federation (later known as the Australian Futsal Federation) for ten years until his death in 2000.[11][27]

Recognition

[edit]Perkins was awarded Jaycees Young Man of the Year in 1966, and NAIDOC Aboriginal of the Year in 1993.[citation needed]

He was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in the Australia Day Honours in 1987, for services to Aboriginal welfare.[33][34]

He was inducted into the Football Federation Australia Football Hall of Fame for services as a player, coach and administrator in 2000.[35]

In 1998 he was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters by the University of Western Sydney, and shortly before his death he was awarded an honorary doctorate of law by the University of Sydney.[34]

Perkins was named by the National Trust of Australia as one of Australia's Living National Treasures.[36]

John Farquharson wrote in his obituary that Perkins "was perhaps not only the most influential Aborigine of modern times, but also must be numbered among the outstanding Australians of the century".[20]

Death and legacy

[edit]In 1975, Perkins wrote his autobiography, entitled A Bastard Like Me.[2]

Perkins died in Sydney on 19 October 2000 of renal failure. During the 1970s, Perkins had a kidney transplant and at the time of his death was the longest post-transplant survivor in Australia.[4][37] In the period immediately following his death, he was known as Kumantjayi Perkins, Kumantjayi being a name used to refer to a deceased person in Arrernte culture.[38] He was given a state funeral.[18] His body was returned to Alice Springs a week after his death.[34]

In 2001, the Dr Charles Perkins AO Memorial Oration and Dr Charles Perkins AO Memorial Prize were established in his honour by the University of Sydney.[39]

In 2009, The Charlie Perkins Trust instituted two scholarships per year to allow Indigenous Australians to study for up to three years at the University of Oxford.[40]

The Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney, designed in 2012 and opened in June 2014,[41][42] was named in honour of Perkins.[43]

In 2013, Australia Post issued a series of postage stamps featuring five eminent Indigenous rights campaigners, including Perkins, Shirley Smith, Neville Bonner, Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Eddie Mabo.[34]

In the arts

[edit]There are several books about Perkins, and artist Bill Leak painted a portrait of him.[34]

In 2018 Paul Kelly wrote a song about Perkins, called "A Bastard Like Me", with the title of the song taken from Perkins' autobiography and the music video featuring footage from his life. It appears on the album Nature.[34]

In film

[edit]- Freedom Ride (1993) is an episode of four-part documentary called Blood Brothers by Rachel Perkins and Ned R. Lander.[44]

- Fire Talker (2009) by Ivan Sen uses archival footage from the early 1960s to 2001 to build an intimate portrait of Perkins' life.[45]

- Remembering Charlie Perkins (2009), in which Gordon Briscoe recalls his friend Perkins' fight for equality and liberty, in the Dr Charles Perkins Memorial Oration.[46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Read, Peter (2001). Charles Perkins: a biography. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books. p. 351. ISBN 0-14-100688-9.

- ^ a b Perkins, Charles (1975). A Bastard like me. Sydney: Ure Smith. p. 199. ISBN 0-7254-0256-3.

- ^ Henningham, Nikki (27 February 2012). "Turner, Patricia". The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia. Canberra, Australia: Australian Research Council. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Papers of Charles Perkins (1936–2000)". National Library of Australia. April 2002. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ "Hetti Perkins, b. 1965". National Portrait Gallery people. 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ a b Perkins, Charles (5 May 1998). "Charles Perkins". Australian Biography (Interview). Interviewed by Robin Hughes. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

I used to clean the toilets, down at South Sydney, and I used to do such a good job they said, 'Why don't you take this on full time?' I used to make them sparkle – all the public toilets around the place, and the one at South Sydney Depot, right down Redfern. And I used to clean them, I had no problem. Any job is a good job. And ah, you know if anybody else can do it I can do it.

- ^ Chlanda, Erwin (18 September 2013). "The Boys who made the Big Time". Alice Springs News. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Sandra (10 January 2022). "Vince Copley had a vision for a better Australia – and he helped make it happen, with lifelong friend Charles Perkins". The Conversation. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Copley, Vince (12 December 2022). "The Wonder of Little Things". HarperCollins Australia. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Charles Perkins". Charles Perkins Centre. The University of Sydney. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ a b Cockerill, Michael (20 April 2001). "Australian football loses a trail-blazer". FIFA. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- ^ "Immigration Nation: Part 3". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ a b Benns, Matthew (7 August 2015). "Deported: Nancy Prasad was the little girl who helped bring down the White Australia policy". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Nicholls, Glenn (2007). Deported: A History of Forced Departures from Australia. UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868409894. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1957–1973: Organisations - National Museum of Australia". National Museum of Australia. 2018. Archived from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ "Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs". Collaborating for Indigenous Rights. 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Pollock, Zoe (2008). "Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs". The Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Charles Perkins AO, b. 1936". National Portrait Gallery. 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Copley, Vince; McInerney, Lea (2022). The Wonder of Little Things. Harper Collins. pp. 2015–2018, 220. ISBN 978-1-4607-1483-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Farquharson, John (16 June 1936). "Perkins, Charles Nelson (Charlie) (1936–2000)". Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Education Services Australia Limited and the National Archives of Australia (2010). "Indigenous activist and leader, Charles Perkins". National Archive of Australia. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Charles Perkins Oration 2015 | Australian Human Rights Commission". humanrights.gov.au. 15 October 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Coombes, Lindon; Gray, Paul (6 August 2020). "Charles Perkins forced Australia to confront its racist past. His fight for justice continues today". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Charles Perkins – Obituary". The Times. The Times Magazine. 20 August 2000. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2008 – via European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights.

- ^ "AFL: Charles Perkins brands AFL and ARL as racist". AAP. 24 May 2000. Retrieved 17 December 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Records of the Aboriginal Publications Foundation: MS3781" (PDF). AIATSIS Library. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ a b Perkins, Charles (5 May 1998). "Charles Perkins". Australian Biography (Interview). Interviewed by Robin Hughes. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Jupp, James (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-521-80789-1.

- ^ "$2,000 fee on Perkins waived". The Canberra Times. Vol. 43, no. 12, 392. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 16 August 1969. p. 34. Retrieved 10 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Soccer club faces censure over Perkins". The Canberra Times. Vol. 43, no. 12, 349. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 27 June 1969. p. 18. Retrieved 10 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Perkins stunned by club's refusal to cut fee". The Canberra Times. Vol. 43, no. 12, 385. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 8 August 1969. p. 18. Retrieved 10 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "SPORTS SHORTS". Woroni. Vol. 22, no. 3. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 25 March 1970. p. 14. Retrieved 10 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) entry for Perkins, Charles Nelson". Australian Honours Database. Canberra, Australia: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 26 January 1987. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

AO AD 87. For service to Aboriginal welfare

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Mark J. (17 March 2019). "Charles Perkins: Australia's Nelson Mandela". Alice Springs News. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "The Australian Football Hall of Fame". Football Federation Australia. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ^ "List of Treasures". National Trust. Archived from the original on 10 February 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Hetty Perkins discusses kidney research fundraising". PM. ABC Radio. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "Should you name a dead Aboriginal person?". Creative Spirits, Jens Korff. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Dr Charles Perkins AO Annual Memorial Oration and Prize". University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Funding for Indigenous Oxford scholarships (ABC News)". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ The Charles Perkins Centre Launch on YouTube

- ^ "World first Charles Perkins Centre officially opens" (PDF) (Press release). Sydney Local Health District. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Building starts on Charles Perkins Centre". ArchitectureAU. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Aboriginal resources > Movies > Freedom Ride". Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Message Sticks, Australia's only Indigenous film festival celebrates its 10th anniversary" (Press release). Sydney Opera House. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Gordon Briscoe Remembers His Friend Charlie Perkins". Big Ideas. 6 November 2009. ABC News 24. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- "Perkins, Charles Nelson (Charlie) (1936–2000)". Indigenous Australia. Contains details extracted from A Bastard Like Me, as well as links to numerous additional resources.

- Charles Perkins at the National Archives of Australia

- "Papers of Charles Perkins". Trove. Catalogue entry to his papers held by the National Library of Australia, which also contains much useful information

- Charles Perkins on the National Film & Sound Archive website

- The Charlie Perkins Scholarship Trust

- 1936 births

- 2000 deaths

- People from Alice Springs

- Australian public servants

- Australian men's soccer players

- Australian expatriate men's soccer players

- Indigenous Australian soccer players

- Australian soccer managers

- Sydney Olympic FC players

- Bishop Auckland F.C. players

- Kidney transplant recipients

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- Sydney Olympic FC managers

- Australian indigenous rights activists

- University of Sydney alumni

- Arrernte people

- Australian people of Irish descent

- 20th-century Australian sportsmen