Fairchild Channel F

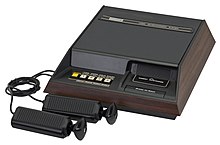

Channel F and its two controllers | |

| Also known as | Fairchild Video Entertainment System |

|---|---|

| Developer | Jerry Lawson |

| Manufacturer | Fairchild Camera and Instrument |

| Type | Home video game console |

| Generation | Second |

| Release date | |

| Lifespan | 1976–1983 |

| Introductory price | US$169.95 (equivalent to $910 in 2023) |

| Discontinued | 1983 |

| Units sold | c. 310,000 (as of 1979)[1] |

| Media | ROM cartridge |

| CPU | Fairchild F8 |

| Memory | 64 bytes RAM 2 KB video buffer |

| Display | c. 104 × 60 pixels (of 128 x 64 VRAM) |

| Controller input | Joystick/digital paddle, JetStik (has added fire button) |

The Fairchild Channel F, short for "Channel Fun",[1] is a home video game console, the first to be based on a microprocessor and to use ROM cartridges (branded 'Videocarts') instead of having games built-in. It was released by Fairchild Camera and Instrument in November 1976 across North America[2] at a retail price of US$169.95 (equivalent to $910 in 2023). It was launched as the "Video Entertainment System", but Fairchild rebranded their console as "Channel F" the next year while keeping the Video Entertainment System descriptor.

The Fairchild Channel F sold only about 350,000 units before Fairchild sold the technology to Zircon International in 1979, trailing well behind the Atari VCS.[1] The system was discontinued in 1983.[3]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2020) |

In 1974, Alpex Computer Corporation employees Wallace Kirschner and Lawrence Haskel developed a home video game prototype consisting of a base unit centered on an Intel 8080 microprocessor and interchangeable circuit boards containing ROM chips that could be plugged into the base unit. The duo attempted to interest several television manufacturers in the system, but were unsuccessful. Next, they contacted a buyer at Fairchild, which sent engineer Jerry Lawson to evaluate the system. Lawson was impressed by the system and suggested Fairchild license the technology, which the company did in January 1976.[1][4]

Lawson worked with industrial designer Nick Talesfore and mechanical engineer Ronald A. Smith to turn the prototype into a viable project. Jerry Lawson replaced the 8080 with Fairchild's own F8 CPU; while Nick Talesfore and Ron Smith were responsible for adapting the prototype's complex keyboard controls into a single control stick, and encasing the ROM circuit boards into plastic cartridges reminiscent of 8-track tapes.[4][5][6] Talesfore and Smith collaborated on the styling and function of the 8 degrees of freedom hand controller. They were responsible for the design of the hand controllers, console, and video game cartridges. Talesfore also worked with graphic designer Tom Kamafugi, who did the original graphic design for the early video cartridges cartons.

John Donatoni, the marketing director of Fairchild's video games division, stated that the console followed the razor and blades model where they would sell the "hardware, and then we're going to make the profit on the cartridge sales". Their marketing campaign was conducted by Ogilvy.[7]

Fairchild announced the console at the Consumer Electronics Show on June 14, 1976, and the Federal Communications Commission approved it for sale on October 20.[8][9][10] It was released as the Video Entertainment System (VES) at the price of $169.95, but renamed to the Channel F the next year. Channel F was unable to compete against Atari's Video Computer System (VCS) as the console only had 22 games compared to Atari's 187.[11] Marketing for the console included an event featuring Ken Uston playing Video Blackjack[12] and commercials starring Milton Berle.[7]

The console was licensed in Europe to television manufacturers[13] and led to the clone consoles of Ingelen Telematch Processor in Austria, Barco Challenger in Belgium, ITT Telematch-Processor and Nordmende Color Teleplay μP in Germany, Dumont Videoplay System and Emerson Videoplay System in Italy, Luxor TV-Datorspel and Luxor Video Entertainment Computer in Sweden, and Grandstand Video Entertainment Computer in the United Kingdom. Both models of the Saba Videoplay were sold in Germany and Italy.[14][15]

Channel F System II

[edit]

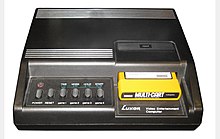

Lawson moved on to form his own company, Video Soft in 1980.[16] Talesfore continued working on the system at Fairchild, and eventually a number of these improvements resulted in the improved System II. The major changes were that the controllers were now removable, using the Atari joystick port connector (not Atari compatible), and their storage was moved to the back of the machine. The sound was now mixed into the RF modulator so you could adjust it on your TV set instead of a fixed volume internal speaker. The internal electronics were also simplified, with two custom logic chips replacing the standard TTL logic chips. This resulted in a much smaller motherboard which allowed for a smaller, simpler and more modern-looking case design.

Fairchild left the video game market in April 1979.[7] Zircon International acquired the rights to the system and related assets in 1979. The company redesigned the console into the Channel F System II. This featured removable controllers and audio coming from the TV rather than a speaker within the console. It was sold at the price point of $99.95 or $69.95 if the previous console was traded in. Zircon released an additional four games for a final library of 26 games on the console.[17]

Design

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

The Channel F is based on the Fairchild F8 microprocessor, which was innovative compared to other contemporary processors and integrated circuits.[18] Because chip packaging was not initially available with enough pins, a few pins were used to communicate with other chips in the system. At least two chips were necessary to set up an F8 processor system to be able run any code. The savings from using standard pin layout enabled the inclusion of 64 bytes of internal scratchpad RAM in the CPU. The VES/Channel F, as well as the System II, had one CPU and two storage chips (PSU:s). (A single-chip variant of the F8 was used by the VideoBrain computer system).

The Channel F is able to use one plane of graphics and one of four background colors per line, with three plot colors to choose from (red, green, and blue) that turns white if the background is set to black, at a resolution of 128 × 64, with approximately 104 × 60 pixels visible on the TV screen. This VRAM or framebuffer was "write only" and not usable for anything else. 64 bytes of scratchpad RAM are available for general use - half the amount of the later Atari 2600.[19][20] The Maze game (Videocart-10) and Hangman game (Videocart-18) used 1024 bits of on-cartridge static RAM connected directly to one PSU port - adding to the cost of manufacturing it. The Chess game contained considerably more on-cartridge RAM than that, 2048 Bytes accomplished by using an F8 memory interface circuit to be able to use industry standard ROM and RAM. The F8 processor at the heart of the console is able to provide AI to allow for player versus computer matches, a first in console history. All previous machines required a human opponent. Tic-Tac-Toe on Videocart-1 had this feature, it was only for one player against the machine. The same is true for the chess game, which could have very long turn times for the computer as the game progressed, depending on the set difficulty.[citation needed]

The Channel F is also the first video game console to feature a pause function; There is a 'Hold' button on the main unit of the console which allows players to freeze inside the two built-in games and change several game settings in the meantime. Button is controlled through code so it was used for other things in other games.[21]

Controllers

[edit]The controllers for the system were conceived by Lawson and built by Nicholas Talesfore.[22]

Unlike the Atari 2600 joystick, Channel F controllers lack a base. Instead, the main body is a large handgrip with a triangular "cap" on top, which can move in eight directions. It could be used as both a joystick and paddle (twist), and not only could it be pushed down to operate as a fire button, it could be pulled up as well.[23] The model 1 unit contained a small compartment for storing the controllers when moving it or when not in use. The System II featured detachable controllers with two holders at the back to wind the cable around and to store the controller in. Zircon later offered a special controller that featured an action button on the front of the joystick. It was marketed by Zircon as "Channel F Jet-Stick" in a letter sent out to registered owners before Christmas 1982.[24]

One feature, unique to the console, is the 'hold' button, which allows the player to freeze the game, change the time or speed of the game.[25] The hold function is however not universal (like the hardwired reset) as the four buttons are set up in code. The programmer can choose their function/purpose. The text labels explains the button functions in the built-in games (and some of the Videocarts).

Despite the failure of the Channel F, the joystick's design was so popular—Creative Computing called it "outstanding"— that Zircon also released an Atari joystick port-compatible version, the Video Command Joystick,[26] first released without the extra fire button. Before that, only the downwards plunge motion was connected and acted as the fire button; the pull-up and twist actions were not connected to anything.[citation needed]

Technical specifications

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

- CPU microprocessor: Fairchild F8 (8-bit)[27] operating at 1.7897725 MHz (NTSC colorburst/2). PAL gen. 1: 2.0000 MHz, gen. 2: 1.9704972 MHz (PAL colorburst*4/9)

- RAM: 2 KB VRAM (128 × 64 × 2 bits)[28] for the write only framebuffer (four Mostek MK4027 or MK4015 4Kx1bit DRAMs), plus 64 bytes of scratchpad memory.[29]

- Additional SRAM supported via add-in cartridges. Maze and Hangman has 1K x 1 bit, expanded with 3853 SMI Chess has 2048 Bytes.

- Resolution: Approximately columns 3-107 and rows 2-62 are visible, depending on TV. (Columns 125 and 126 controls palette per row). Although VRAM could cover 128 × 64 pixels,[30]

- Refresh rate: 60 Hz[31]

- Colors: 8 colors[32] (either black/white lines or lines using background grey/blue/green with red, green or blue pixels)

- Audio: 120 Hz, 500 Hz and 1 kHz beeps (can be modulated to produce different tones). Audio quality is quite superior on the System II, versus the original model.

- Input: two custom game controllers, hardwired to the console (original release) or removable (Channel F System II)

- Output: RF modulated composite video signal, cord hardwired to console in original release, detachable in System II.

Games

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

Twenty-seven cartridges, termed "Videocarts", were officially released to consumers in the United States during the ownership of Fairchild and Zircon, the first twenty-one of which were released by Fairchild. Several of these cartridges were capable of playing more than one game and were typically priced at $19.95 (equivalent to $91 in 2020).[33][34] The Videocarts were yellow and approximately the size and overall texture of an 8 track cartridge.[35] They usually featured colorful label artwork. The earlier artwork was created by nationally known artist Tom Kamifuji and art directed by Nick Talesfore.[citation needed] The console contained two built-in games, Tennis and Hockey, which were both advanced Pong clones. In Hockey, the reflecting bar could be changed to different diagonals by twisting the controller knob and could move all over the playing field. Tennis was much like the original Pong.

A sales brochure from 1978 listed "Keyboard Videocarts" for sale. The three shown were K-1 Casino Poker, K-2 Space Odyssey, and K-3 Pro-Football. These were intended to use the Keyboard accessory, which is displayed on the Channel F II box. All further brochures, released after Zircon took over from Fairchild, never listed this accessory nor anything called a Keyboard Videocart.

There was one cartridge released outside the numbered series, listed as Videocart-51 and simply titled "Demo 1". This Videocart was shown in a single sales brochure released shortly after Zircon acquired the company. It has not been seen listed for sale after this single brochure which was sent out in the winter of 1979.

| Title | Release date | Genre |

|---|---|---|

| Hockey (integrated) | 1976 | Sports |

| Tennis (integrated) | 1976 | Sports |

| Videocart-1: Tic-Tac-Toe, Shooting Gallery, Doodle, Quadra-Doodle | 1976 | Trivia, shooter |

| Videocart-2: Desert Fox, Shooting Gallery | 1976 | Action, shooter |

| Videocart-3: Video Blackjack | 1976 | Gambling |

| Videocart-4: Spitfire | 1977 | Action, shooter |

| Videocart-5: Space War | 1977 | Action, shooter |

| Videocart-6: Math Quiz I (Addition & Subtraction) | 1977 | Educational |

| Videocart-7: Math Quiz II (Multiplication & Division) | 1977 | Educational |

| Videocart-8: Magic Numbers (Mind Reader & Nim) | 1977 | Trivia |

| Videocart-9: Drag Race | 1977 | Racing |

| Videocart-10: Maze, Jailbreak, Blind-Man's-Bluff, Trailblazer | 1977 | Maze |

| Videocart-11: Backgammon, Acey-Deucey | 1977 | Trivia |

| Videocart-12: Baseball | 1977 | Sports |

| Videocart-13: Robot War, Torpedo Alley | 1977 | Platform, action |

| Videocart-14: Sonar Search | 1977 | Strategy |

| Videocart-15: Memory Match 1, Memory Match 2 | 1978 | Puzzle |

| Videocart-16: Dodge' It | 1978 | Platform, action |

| Videocart-17: Pinball Challenge | 1978 | Pinball |

| Videocart-18: Hangman | 1978 | Puzzle |

| Videocart-19: Checkers | 1978 | Trivia |

| Videocart-20: Video Whizball | 1978[36] | Miscellaneous |

| Videocart-21: Bowling | 1978 | Sports |

| Chess (Schach) | 1979 (SABA Videoplay, German-exclusive) | Board |

| Werbetextcassette electronic partner | 19?? (German-exclusive) | Advertising |

| Videocart-22: Slot Machine | 1980 | Gambling |

| Videocart-23: Galactic Space Wars | 1980 | Action, shooter |

| Videocart-24: Pro Football | 1981 | Sports |

| Videocart-25: Casino Poker | 1981 | Gambling |

| Videocart-26: Alien Invasion | 1981[36] | Action, shooter |

| Videocart-27: Pac-Man | 2009[37] | Maze, Homebrew |

| Kevin vs Tomatoes | 2018 | Maze, Homebrew |

| Videocart-28: Tetris | 2019 | Puzzle, Homebrew |

| trimerous | 2020 | Sports, Shooter, Homebrew |

| Videocart-29: The Arlasoft Collection | 2022 | Puzzle, Shooter, Homebrew |

- Democart (was briefly available to the general public)

- Democart 2

Unreleased carts:

- Keyboard Videocart-1: Casino Poker

- Keyboard Videocart-2: Space Odyssey

- Keyboard Videocart-3: Pro-Football

German electronics manufacturer SABA also released a few compatible carts different from the original carts: translation in Videocart-1 Tic-Tac-Toe to German words, Videocart-3 released with different abbreviations (German), and Videocart-18 changed graphics and has a German word list.

In 2021, a number of new 'Homebrew' games were released on itch.io by retro developer Arlasoft. These included ports of mobile puzzle games Tents & Trees, 2048 and Threes, as well as a port of the classic arcade shooter Centipede. Through a secret button combination a hidden game could also be started, the box and instruction booklet has multiple hints about the needed code.

These were released on cartridge as Videocart-29.[38]

Reception

[edit]

The Channel F had beaten the Atari VCS to the market, but once the VCS was released, sales of the Channel F fell, attributed to the types of games that were offered. Most of the Channel F titles were slow-paced educational and intellectual games, compared to the action-driven games that launched with the VCS. Even with the redesigned Channel F II in 1978, Fairchild was unable to meet the sales that the VCS and its games were generating. By the time Fairchild sold the technology to Zircon in 1979, around 350,000 total units had been sold.[1]

Ken Uston reviewed 32 games in his book Ken Uston's Guide to Buying and Beating the Home Video Games in 1982, and rated some of the Channel F's titles highly; of these, Alien Invasion and Video Whizball were considered by Uston to be "the finest adult cartridges currently available for the Fairchild Channel F System".[39] The games on a whole, however, rated last on his survey of over 200 games for the Atari, Intellivision, Astrocade and Odyssey consoles, and contemporary games were rated "Average" with future Channel F games rated "below average".[40] Uston rated almost one-half of the Channel F games as "high in interest" and called that "an impressive proportion" and further noted that "Some of the Channel F cartridges are timeless; no matter what technological developments occur, they will continue to be of interest." His overall conclusion was that the games "serve a limited, but useful, purpose" and that the "strength of the Channel F offering is in its excellent educational line for children".[41]

In 1983, after Zircon announced its discontinuation of the Channel F, Video Games reviewed the console. Calling it "the system nobody knows", the magazine described its graphics and sounds as "somewhat primitive by today's standards". It described Space War as "may be the most antiquated game of its type still on the market", and rated the 25 games for the console with an average "interest grade" of three ("not too good") on a scale from one to ten and "skill rating" at an average 4,5 of 10. The magazine stated, however, that Fairchild "managed to create some fascinating games, even by today's standards", calling the poker game Casino Royale (actually Videocart-25, Casino Poker) "the best card game, from blackjack to bridge, made for any TV-game system". It also favorably reviewed Dodge-It ("simple but great"), Robot War ("Berzerk without guns"), and Whizball ("thoroughly original ... hockey with guns"), but concluded that only those interested in nostalgia, video game collecting, or card games would purchase the Channel F in 1983.[42][43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel F Patent, FCC Approval, & Launch Brochure". Fndcollectables.com.

- ^ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2018-11-21). The Routledge Companion to Media Technology and Obsolescence. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-44266-2.

- ^ a b Zell-Breier, Sam (June 11, 2021). "The Untold Truth Of Jerry Lawson, The Father Of The Video Game Cartridge". Looper. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Alexander (2019). They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies That Shaped the Video Game Industry, Volume I. CRC Press. pp. 318–320. ISBN 9781138389908.

- ^ US Patent 1978, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Bunch 2023.

- ^ Fairchild 1977, p. 6.

- ^ "New Products". Oakland Tribune. June 15, 1976. p. F45. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Games TV viewers play". San Francisco Examiner. June 16, 1976. p. 60. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wolf 2012, p. 62-64.

- ^ "Meet Ken Uston author of "The Big Player" and watch him play blackjack on the Fairchild programable Channel F". Reno Gazette-Journal. August 10, 1977. p. 43. Archived from the original on August 31, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fairchild 1977, p. 15.

- ^ Wolf 2012, p. 64.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel F Models & Clones". Video Game Console Library. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024.

- ^ "Jerry Lawson is one of the most important Silicon Valley pioneers you've never heard of — here's why". CNBC. 30 October 2021. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ Wolf 2012, pp. 63–64.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel-F / Saba".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hanson, Christopher (2018). Game Time: Understanding Temporality in Video Games. Indiana University Press. p. 61.

- ^ Wolf 2012, p. 67.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Robert. "Fairchild Channel F Video Entertainment System: The first modern game console". The Rev. Rob Times. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Channel F Jet-Stick Advert" (JPG). Fndcollectables.com. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "OLD-COMPUTERS.COM : The Museum". Old-computers.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Ahl, David H.; Rost, Randi J. (1983), "Blisters And Frustration: Joysticks, Paddles, Buttons and Game Port Extenders for Apple, Atari and VIC", Creative Computing Video & Arcade Games, 1 (1): 106ff

- ^ Fairchild 1977, pp. 10.

- ^ US Patent 1978, p. 8.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel F". www.oldcomputers.it. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel F Specs & Manuals". Video Game Console Library. Archived from the original on September 3, 2024.

- ^ As emulated by MAME; see source code at "MAME". GitHub. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Wolf 2012, p. 65.

- ^ "1976 commercial trailer". YouTube. 10 November 2011.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b Wolf 2012, p. 70.

- ^ "Channel F – Videocart 27: Pac-Man (USC)". ConsoleCity. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Fairchild Channel F - Collection by Arlasoft". itch.io. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ Uston, Ken. Ken Uston's Guide to Buying and Beating the Home Video Games (Signet, 1982) p.605

- ^ Uston, Ken. Ken Uston's Guide to Buying and Beating the Home Video Games (Signet, 1982) p.20.

- ^ Uston, Ken. Ken Uston's Guide to Buying and Beating the Home Video Games (Signet, 1982) p.603 and p.23.

- ^ Dionne, Roger (March 1983). "Channel F: The System Nobody Knows". Video Games. pp. 73–75. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ "Video Games Vol.1 #6 -83". Archive.org. March 1983. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

Works cited

[edit]- Bunch, Kevin (2023). "Selling the First Programmable Game Console: An Interview with John Donatoni about the Channel F". ROMchip: A Journal of Game Histories. 5 (2).

- Wolf, Mark, ed. (2012). Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814337226.

- "Fairchild Annual Report to Employees 1976" (PDF) (Press release). Fairchild Camera and Instrument. 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-10.

- "U.S Patent 4,095,791" (PDF). United States Patent and Trademark Office. June 20, 1978. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-10.

External links

[edit]- The Dot Eaters article with a history of the Channel F and games

- Interview with designer Jerry Lawson

- MobyGames list Archived 2020-01-26 at the Wayback Machine of Channel F games

- Channel F wiki programming and electronics as well as a gallery of labels, instructions, and boxes.

- Patent: Cartridge programmable video game apparatus US 4095791 A

- The Untold Story of the Invention of the Video Game Cartridge—how the Channel F's video game cartridge was created (January 22, 2015).

- Channel F was 1977's top game system—before Atari wiped it out at The A.V. Club's AUX (4/09/2017)

- Channel F games playable for free in the browser at the Internet Archive Console Living Room

- Channel F emulation of the BIOS