Chalk talk

A chalk talk is an illustrated performance in which the speaker draws pictures to emphasize lecture points and create a memorable and entertaining experience for listeners. Chalk talks differ from other types of illustrated talks in their use of real-time illustration rather than static images. They achieved great popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appearing in vaudeville shows, Chautauqua assemblies, religious rallies, and smaller venues. Since their inception, chalk talks have been both a popular form of entertainment and a pedagogical tool.

Early history

[edit]

One of the earliest chalk talk artists was a prohibition illustrator named Frank Beard (1842–1905).[1][2] Beard was a professional illustrator and editorial cartoonist who published in The Ram's Horn, an interdenominational social gospel magazine.[3] Beard's wife was a Methodist, and when the women of their church asked Beard to draw some pictures as part of an evening of entertainment they were planning, the chalk talk was born.[4] In 1896, Beard published Chalk Lessons; or, The Black-board in the Sunday School, which he dedicated to the Rev. Albert D. Vail "[t]hrough whose simple Black-board teaching I was first led to search the Scriptures and my own heart."[2]

Public performance

[edit]Like magic lantern shows and Lyceum lectures, chalk talks, with their presentation of images changing in real time, could be educational as well as entertaining.[5] They were choreographed performances "where the images would become animate, melding one into another in an orderly and progressive way" to tell a story.[6] Chalk talks began to be used for religious rallies[7] and became popular acts in vaudeville and at Chautuaqua assemblies.[8] Some performers, such as James Stuart Blackton, created acts around "lightning sketches," drawings which were rapidly modified as the audience looked on. "Tricks" or illustrative techniques used by performers were called "stunts."[9] The seemingly magical stunts, and the chalk talk artist's power to transform simple images before their audiences' eyes, appealed to magicians. Cartoonist and magician Harlan Tarbell performed as a chalk-talker and published several chalk talk method books.[10]

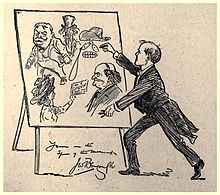

Winsor McCay began doing vaudeville chalk talks in 1906.[11] In his The Seven Ages of Man vaudeville act, he drew two infant faces, a boy and a girl, and progressively aged them.[12][13] Popular illustrator Vernon Grant was also known for his vaudeville circuit chalk talks. Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist John T. McCutcheon was a popular chalk talk performer.[9] Artist and suffragist Adele Goodman Clark set up her easel on a street corner to convince listeners to support woman suffrage.[14] Canadian cartoonist John Wilson Bengough toured internationally, giving chalk talks both for entertainment and in support of causes including woman suffrage and prohibition.[15]

Animation

[edit]Chalk talks contributed to the development of early animated films, such as The Enchanted Drawing by James Stuart Blackton and his partner, Alfred E. Smith.[13] Blackton's Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) was another early animated film with its roots in chalk talks.[16] For his early films, Winsor McCay borrowed Blackton's image of the artist standing before drawings that come to life.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Scutts, Joanna (October 30, 2015). "Frank Beard: The Cartoonist Who Drew America Dry". Tales of the Cocktail Foundation. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Beard, Frank (1896). Chalk Lessons, or The Blackboard in the Sunday School. New York: Excelsior Publishing House.

- ^ "The Ram's Horn". eHistory. History Department. Ohio State University. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "Frank Beard's Chalk Talk". Isabella Alden. 2015-01-12. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ Lush, Paige (2013). Music in the Chautauqua Movement: From 1874 to the 1930s. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7864-7315-1.

- ^ Lindquist, Benjamin (2019-03-01). "Slow Time and Sticky Media: Frank Beard's Political Cartoons, Chalk Talks, and Hieroglyphic Bibles, 1860–1905". Winterthur Portfolio. 53 (1): 41–84. doi:10.1086/703977. ISSN 0084-0416. S2CID 197811853.

- ^ "Thousands of Working Men Attended the Great Noon Meeting at the Union Iron Works Yesterday". The San Francisco Call. July 13, 1897. p. 1. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ Tydeman, William (1994). "New Mexico Tourist Images". Essays in Twentieth-Century New Mexico History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780826314833.

- ^ a b Bartholomew, Charles L. (1922). Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentation; A Handbook of Practice and Performance in Pictorial Expression of Ideas. University of California Libraries. Chicago : Frederick J. Drake and co., publishers. pp. 100–122.

- ^ "Harlan Tarbell, Chalk Talk books". WorldCat.org. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ Winsor McCay at filmreference.com

- ^ a b Canemaker, John (2018). Winsor McCay. His Life and Art. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781138578869.

- ^ a b Stabile, Carol A. and Mark Harrison. Prime Time Animation: Television Animation and American Culture. Routledge, 2003.

- ^ Hyde, Jo (September 16, 1956). "Personality Profile: Miss Adele Clark". Richmond Times-Dispatch. p. 25.

- ^ Bengough, J. W. (1922). Bengough's Chalk-Talks: A Series of Platform Addresses on Various Topics, With Reproductions of the Impromptu Drawings With Which They Were Illustrated. Toronto: Musson. pp. 39.

- ^ Popova, Maria (2010-03-23). "The Enchanted Drawing: Blackton's Early Animation". Brain Pickings. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

External links

[edit]- Charles L. Bartholomew's Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentation: a handbook of practice and performance in pictorial expression of ideas

- Frank Beard, Chalk lessons, or The blackboard in the Sunday school

- Daniel Carter Beard, "How to Prepare and Give a Boys' Chalk-Talk," New Ideas for American Boys; the Jack of All Trades

- J. W. Bengough, Bengough's Chalk-Talks: A Series of Platform Addresses on Various Topics, With Reproductions of the Impromptu Drawings With Which They Were Illustrated.

- Golden Chalk Classics (chalk talk archive)

- William Allen Bixler, Chalk Talk Made Easy

- Bert Joseph Griswold, Crayon and character : truth made clear through eye and ear or ten-minute talks with colored chalks

- Ash Davis Cartoonist Pictured Fun Quickly Done. Ash Davis promotional materials, Redpath Chautauqua Collection, University of Iowa Libraries