Catch wrestling

| |

| Also known as | Catch-as-catch-can (CACC) Lancashire wrestling Loose-hold Hooking Rough and tumble Fair fight Shoot wrestling |

|---|---|

| Focus | Wrestling, Grappling |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Famous practitioners | (see notable practitioners) |

| Parenthood | English wrestling (Cumberland, Westmorland, Cornish, Devonshire, Lancashire) Indian pehlwani[1][2] Irish collar-and-elbow, Greek Pankration, American rough and tumble |

| Descendant arts | Freestyle wrestling, professional wrestling, shoot wrestling, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, folkstyle wrestling, Luta Livre, Sambo, mixed martial arts (MMA) |

| Olympic sport | Yes (as amateur freestyle wrestling) since 1904 |

Catch wrestling (originally catch-as-catch-can) is an English style of wrestling with looser rules than forms like Greco-Roman wrestling. For example, catch wrestling allows leg attacks and joint locks. It was popularised by wrestlers of travelling funfairs who developed their own submission holds, referred as "hooks" and "stretches", into their wrestling to increase their effectiveness against their opponents.

In the UK, catch wrestling combines several British styles of wrestling (primarily Lancashire,[3] as well as Cumberland, Westmorland,[4] Devonshire[4] and Cornish) along with influences from the Indian pehlwani[1][2] and Irish collar-and-elbow styles of wrestling.

In America by 1840, the phrase "catch as catch can" was used to describe rough and tumble fighting.[5]

The training of many modern submission wrestlers, professional wrestlers and mixed martial artists is founded in catch wrestling through its various incarnations of amateur wrestling.

Professional wrestling, once a legitimate combat sport, was competitive catch wrestling. The original and historic World Heavyweight Wrestling Championship was created in 1905 to identify the best catch-as-catch-can wrestler in the world, before the belt was retired in 1957 and unified with the NWA World Heavyweight Championship. Modern day professional wrestling has its origins in catch wrestling exhibitions at carnivals where predetermined ("worked") matches had elements of performing arts introduced (as well as striking and acrobatic manoeuvres), turning it into an entertainment spectacle.[6] In a few countries, such as in France and Germany, "catch" is still the term used for professional wrestling.[7]

Catch-as-catch-can was included in the 1904 Olympic Games and continued through the 1936 Games; it had new rules and weight categories introduced similar to other amateur wrestling styles, and dangerous moves — including all submission holds — were banned. New rules and regulations were later developed and codified by FILA and amateur catch wrestling became known as freestyle wrestling, which was then considered separate from the dangerous, professional catch style.[8][9]

Other martial arts with origins in catch wrestling include folkstyle wrestling, Sambo, Luta Livre, shoot wrestling, shootfighting and mixed martial arts (MMA).[citation needed][10]

History

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

By 1840 the phrase "catch as catch can"[5] was being used in America to describe their Rough and tumble fighting found in the frontier which was characterized by its lack of strict rules and the use of any and all tactics to achieve victory.

The phrase "catch as catch can" reflected the improvisational nature of the style, where wrestlers utilized whatever holds they could "catch" on their opponent with the primary goal being to make the opponent verbally quit by using grappling techniques including holds and dirty moves associated with the American style at the time.

In 1871 (31 years later), John Graham Chambers, of aquatic and pedestrian fame, and sometime editor of Land and Water, endeavoured to introduce and promote a new system of wrestling at Little Bridge Grounds, West Brompton, which he denominated, "the catch-as-catch-can style; first down to lose".[4] However, the new idea met with little support at the time, and a few years afterward Chambers was induced to adopt the objectionable fashion of allowing the competitors to wrestle on all fours on the ground. This new departure was the forerunner of the total abolition of the sport at that athletic, and within a short period the wrestling, as an item in the programme.[citation needed]

Various promoters of the exercise, notably J. Wannop, of New Cross, attempted to bring the new system prominently before the public, with the view of amalgamating the three English styles viz. the Cumberland and Westmorland, Cornwall and Devon, and Lancashire.[4] The sudden development of the Cumberland and Westmorland Amateur Wrestling Society brought the new style prominently to the front, and special prizes were given for competition in that class at the society's first annual midsummer gathering at the Paddington Recreation Ground, which was attended by Lord Mayor Whitehead and sheriffs in state.

Wrestling on the "catch-as-catch-can" principle was new to many spectators, but it was generally approved of as a great step in advance of the loose-hold system, which includes struggling on the ground and sundry objectionable tactics, such as catching hold of the legs, twisting arms, dislocating fingers, and other items of attack and defence peculiar to Lancashire wrestling.[4]

Catch wrestling drew from international influences, most notably Indian pehlwani wrestling.[1][2] British heavyweight champion Tom Cannon, an early practitioner of catch wrestling, visited British India in 1892, where he was defeated by 21 year-old pehlwani wrestler Kareem Buksh. This led to Indian pehlwani wrestlers being invited to compete in London, including Indian champions such as The Great Gama and Imam Baksh Pahalwan, influencing the development of catch wrestling.[2]

When catch wrestling reached the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it became extremely popular with the wrestlers of the carnivals. The carnivals' wrestlers challenged the locals as part of the carnival's "athletic show" and the locals had their chance to win a cash reward if they could defeat the carnival's strongman by a pin or a submission. Eventually, the carnivals' wrestlers began preparing for the worst kind of unarmed assault and aiming to end the wrestling match with any tough local quickly and decisively via submission. A hook was a technical submission which could end a match within seconds. As carnival wrestlers travelled, they met with a variety of people, learning and using techniques from various other folk wrestling disciplines, especially Irish collar-and-elbow, many of which were accessible due to a huge influx of immigrants in the United States during this era.[citation needed]

Catch wrestling contests also became immensely popular in Europe involving the likes of the Indian heavyweight champion Great Gama, Imam Baksh Pahalwan, Gulam, Bulgarian heavyweight champion Dan Kolov, Swiss champion John Lemm, Americans Frank Gotch, Tom Jenkins, Ralph Parcaut, Ad Santel, Ed Lewis, Lou Thesz and Benjamin Roller, Mitsuyo Maeda from Japan, and Georg Hackenschmidt from Estonia.

Wrestling made a return at the 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis, US, but different from previous editions, wrestling was disputed under catch-as-catch-can rules due the popularity of this particular style in the United States. The competition doubled as the United States Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) wrestling championships, which introduced new rules: it was single elimination tournament, with bouts being six minutes in duration plus an extra three minutes for overtime; in the case that no pinfall was registered, a judge would render the final decision. Six weight classes were introduced and all submission holds were banned.[8][9] In 1912, the Fédération Internationale des Luttes Associées (FILA)—current United World Wrestling—was founded in order to better organize Olympic wrestling. In 1921, FILA set the "rules of the game" which regulated and codified a new ruleset derived from catch; the new name chosen was "freestyle wrestling", which appears to have been a translation of the French lutte libre, which itself is the French translation of catch-as-catch-can. The name was chosen to distance itself from catch wrestling, which had lost reputation due the rise of professional wrestling.[8][9] In 1922 the AAU followed suit and adopted the new freestyle rule-set while abandoning catch-as-catch-can for their amateur competitions.[citation needed]

By the 1920s, most catch wrestling competitions started to become predetermined professional wrestling. As interest in professional matches started to wane, wrestlers began choreographing some of their matches to make the matches less physically taxing, shorter in duration, with better flow, more entertaining—giving emphasis on readable and more impressive moves—and with bigger focus on the personal charisma of the wrestlers, with the introduction of "gimmicks" (in-ring personas) and dramatic storylines surrounding the matches.[11] The "Gold Dust Trio", formed by heavyweight champion Ed "Strangler" Lewis, his manager Billy Sandow and his fellow wrestler Joseph "Toots" Mondt, are credited with pivoting professional wrestling into a pseudo-competitive exhibition, by introducing the modern form of choreographed action-packed wrestling which they dubbed "slam-bang Western-style wrestling", and a new business model where the trio would promote large shows around the country and maintain wrestlers under long-term contracts, leading to the success of the partnership. Soon other promoters followed suit and the industry was fundamentally changed.[12]

In modern times, professional wrestling is regarded as being, by definition, prearranged entertainment and is legally classed as such by legislatures such as New York (19 CRR-NY 213.2) It is nonetheless still feasible to hold catch wrestling competitions with all the rules and trappings of professional wrestling (roped elevated quadrilateral ring, submission and three count pinfall as equal goals, etc.). A rules system for such competition was devised by professional wrestling champion and catch wrestling coach Karl Gotch for fellow catch wrestler Jake Shannon's "King of Catch" tournaments[13] and similar rules were employed for a 2018 tournament in memory of professional wrestling champion and catch wrestling coach Billy Robinson.[14]

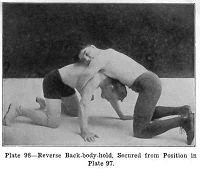

Techniques

[edit]The English term "catch as catch can" is generally understood to mean "catch (a hold) anywhere you can". As this implies, the rules of catch wrestling were more open than the earlier folk styles it was based on, as well as its French Greco-Roman counterpart, which did not allow holds below the waist. Catch wrestlers can win a match by either submission or pin, and most matches are contested as the best two of three falls, with a maximum length of an hour. Often, but not always, the chokehold was barred. Other fouls like fish-hooking and eye-gouging (which were called "rips" or "ripping") were always forbidden.[15]

Pins were the predominant way to win, to the point some matches didn't even include submissions as an additional way; submission holds (also called "punishment holds")[6] were instead exclusively for control and to force the opponent into a pin under the threat of pain and injury. According to Tommy Heyes, student of Billy Riley, there are no registers of a single classical catch wrestler winning by submission.[16] This is the reason why leglocks and neck cranks were emphasized as valid techniques, as while they are difficult to use as finishing moves without a good base, they can be used to force movement.[16] Also, just as today "tapping out" signifies a concession as does shouting out "Uncle!", back in the heyday of catch wrestling rolling to one's back could also signify defeat, as it would mean a pin. Catch-as-catch-can toeholds typically only exert force if the opponent sits still;[16] therefore, Frank Gotch won many matches by forcing his opponent to roll over onto their back with the threat of his signature toehold.[17]

A "hook" can be defined as an undefined move that stretches, spreads, twists, or compresses any joint or limb. Therefore, another name for a catch wrestler was a "hooker," with the similar term "shooter" being relegated to specially skilled hookers.[11][18]

Catch wrestling techniques may include, but are not limited to: the arm bar, Japanese arm bar, straight arm bar, hammerlock, bar hammerlock, wrist lock, top wrist lock, double wrist lock (this hold is also known as the Kimura in MMA, or the reverse Ude-Garami in judo), coil lock (this hold is also known as an Omoplata in MMA), head scissors, body scissors, chest lock, abdominal lock, abdominal stretch, leg lock, knee bar, ankle lock, heel hook, toe hold, half Nelson, and full Nelson.[citation needed]

The rules of catch wrestling would change from venue to venue. Matches contested with side-bets at the coal mines or logging camps favoured submission wins where there was absolutely no doubt as to who the winner was. Meanwhile, professionally booked matches and amateur contests favoured pins that catered to the broader and more gentle paying fan-base. The impact of catch wrestling on modern-day amateur wrestling is also well established. In the film Catch: The Hold Not Taken, US Olympic gold medallist Dan Gable talks of how when he learned to wrestle as an amateur the style was known locally, in Waterloo, Iowa, as catch-as-catch-can. The wrestling tradition of Iowa is rooted in catch wrestling as Farmer Burns and his student Frank Gotch are known as the grandfathers of wrestling in Iowa.[citation needed]

Martial arts

[edit]Judo

[edit]A notable match in 1914 was between two prime representatives of their respective crafts: the German-American catch wrestler Ad Santel was the world light heavyweight champion in catch wrestling, while Tokugoro Ito, a fifth-degree black belt in judo, claimed to be the world judo champion. Santel defeated Ito and proclaimed himself world judo champion.[citation needed]

The response from Jigoro Kano's Kodokan was swift and came in the form of another challenger, fourth-degree black belt Daisuke Sakai. Santel, however, still defeated the Kodokan Judo representative. The Kodokan tried to stop the hooker by sending men like fifth-degree black belt Reijiro Nagata (who Santel defeated by TKO). Santel also drew with fifth-degree black belt Hikoo Shoji. The challenge matches stopped after Santel gave up on the claim of being the world judo champion in 1921 in order to pursue a career in full-time professional wrestling. Although Tokugoro Ito avenged his loss to Santel with a choke,[19] official Kodokan representatives proved unable to imitate Ito's success. Just as Ito was the only Japanese judoka to overcome Santel, Santel was the only Western catch-wrestler on record as having a win over Ito, who also regularly challenged other grappling styles.[citation needed]

Mixed martial arts

[edit]Karl Gotch was a catch wrestler and a student of Billy Riley's "Snake Pit" gym in Wigan, then in Lancashire. Gotch started to teach catch wrestling to Japanese professional wrestlers in the 1960s and continued to do so for many years. He first trained the likes of Antonio Inoki, Tatsumi Fujinami, Hiro Matsuda, Osamu Kido, then others including Satoru Sayama (Tiger Mask), Akira Maeda, and Yoshiaki Fujiwara. Starting from 1976, one of these professional wrestlers, Inoki, hosted a series of mixed martial arts bouts against the champions of other disciplines, including a legitimate mixed-rules match against boxer Muhammad Ali. This resulted in unprecedented popularity of the clash-of-styles bouts in Japan. His matches showcased catch wrestling moves like the sleeper hold, cross arm breaker, seated armbar, Indian deathlock and keylock.[citation needed]

Gotch's students formed the original Universal Wrestling Federation (Japan) in 1984 with Akira Maeda, Satoru Sayama, and Yoshiaki Fujiwara as the top grapplers showcasing shoot-style matches. The UWF movement was led by catch wrestlers and gave rise to the mixed martial arts boom in Japan. Wigan stand-out Billy Robinson soon thereafter began training MMA veteran Kazushi Sakuraba. Lou Thesz trained MMA veteran Kiyoshi Tamura. Catch wrestling forms the base of Japan's martial art of shoot wrestling. Japanese professional wrestling and a majority of the Japanese fighters from Pancrase, Shooto and the now defunct RINGS bear links to catch wrestling. Randy Couture, Kazushi Sakuraba, Kamal Shalorus, Masakatsu Funaki, Takanori Gomi, Shinya Aoki and Josh Barnett, among other mixed martial artists, study catch wrestling as their primary submission style.[20]

The term no holds barred was used originally to describe the wrestling method prevalent in catch wrestling tournaments during the late 19th century wherein no wrestling holds were banned from the competition, regardless of how dangerous they might be. The term was later applied to mixed martial arts matches, especially at the advent of the Ultimate Fighting Championship.[21]

Chain wrestling

[edit]Chain wrestling, also called chain wrestling sequences, is a sequence of traditional grappling moves usually employed near the start of a match. More common in Japan, the UK and Mexico than in the US.[22] Chain wrestling also shares components with Indian leg wrestling and barefoot wrestling, in the sense of seamless transitions between holds and the movement of both competitors.[23]

Notable practitioners

[edit]- Gene Anderson

- Shinya Aoki

- Bob Backlund

- Josh Barnett

- Shayna Baszler

- Farmer Burns

- Bryan Caraway

- Gokor Chivichyan

- Allen Coage

- Randy Couture

- Yoshiaki Fujiwara

- Masakatsu Funaki

- Masakazu Imanari

- Verne Gagne

- Jack Gallagher

- Frank Gotch

- Karl Gotch

- George Hackenschmidt

- Dennis Hallman

- Stu Hart

- Lee Hasdell

- Danny Hodge

- Antonio Inoki

- Demetrious Johnson

- Marty Jones

- Karol Kalmikoff

- Dan Koloff

- Gene LeBell

- Ed "Strangler" Lewis

- Evan Lewis

- Abraham Lincoln

- Neil Melanson

- Shigeo Miyato

- Erik Paulson

- John Pesek

- William Regal

- Billy Riley

- Billy Robinson

- Kazushi Sakuraba

- Ad Santel

- Frank Shamrock

- Ken Shamrock

- Dick Shikat

- Davey Boy Smith Jr.

- Joe Stecher

- Ray Steele

- Hideki Suzuki

- Minoru Suzuki

- Kiyoshi Tamura

- Lou Thesz

- Stanislaus Zbyszko

- Wladek Zbyszko

- Dynamite Kid

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Pitting catch wrestling against Brazilian jiu-jitsu". The Manila Times. 8 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Nauright, John; Zipp, Sarah (3 January 2020). Routledge Handbook of Global Sport. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-317-50047-6.

- ^ "Submission Wrestling". aspullolympicwrestlingclub.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 April 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Armstrong, Walter (1890), Wrestling

- ^ a b Longstreet, Augustus Baldwin. Georgia Scenes. 1840, pp. 53-64. Quoted in Parramore's article, p. 61.

- ^ a b Slack, Jack (4 February 2016). "Kayfabe Time Capsule: The Real Techniques of Professional Wrestling". Fightland. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Catch : l'histoire d'un sport spectacle marié avec la télé du 09 mars 2013". France Inter (in French). 9 March 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b c International Federation of Associated Wrestling Styles. "Freestyle Wrestling". FILA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ a b c Nash, John S. (13 August 2012). "The Olympic History of Catch Wrestling". Bloody Elbow. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Nauright, John; Zipp, Sarah (2020). Routledge Handbook of Global Sport. Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-317-50047-6.

- ^ a b Bob Backlund, Robert H. Miller, Backlund: From All-American Boy to Professional Wrestling's World Champion

- ^ Solomon, Brian (15 June 2010). WWE Legends. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451604504. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ "Say Uncle! Catch-as-Catch-Can" Jake Shannon, ECW Press 2011, p201

- ^ Snake Pit U.S.A. Catch Wrestling Association (21 July 2018). "Curran Jacobs vs. Erik Hammer: 2018 Catch Wrestling World Championship/Snake Pit U.S.A." YouTube.

- ^ Chuck Hustmyre, Twisted Technique: Catch-as-Catch-Can Wrestling Descended from the Original No Holds Barred Fighting Art, December 2003, Black Belt magazine

- ^ a b c Jack Slack (17 October 2016). "The Continued Catch Wrestling Adventures of Minoru Suzuki". Fightland. Vice. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Frank Gotch: World's Greatest Wrestler, Publisher: William s Hein & Co (January 1991), ISBN 0-89941-751-5

- ^ Jim Smallman, I'm Sorry, I Love You: A History of Professional Wrestling

- ^ "Ito threw Santell (sic) around the ring like a bag of sawdust… When Ad gasped for air, the Japanese pounced upon him like a leopard and applied the strangle hold. Santell gave a couple of gurgles, turned black in the face and thumped the floor, signifying he had enough." -- Howard Angus, Los Angeles Times, 1 February 1917

- ^ Michael David Smith (20 January 2010). "Randy Couture 'Moving Away From a Jiu Jitsu Mentality'". MMA Fighting. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ^ "catch: the hold not taken". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2016. Catch: the hold not taken documentary DVD 2005

- ^ Shoemaker, David (13 August 2014). "Grantland Dictionary: Pro Wrestling Edition". Grantland. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Chain Wrestling". fanaticwrestling.com. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

External links

[edit]- The Snake Pit – internationally regarded as the home of catch wrestling, based in Wigan, England.

A