Radford, Virginia

Radford, Virginia | |

|---|---|

Main Street in Radford, Virginia. | |

| Nickname: The New River City | |

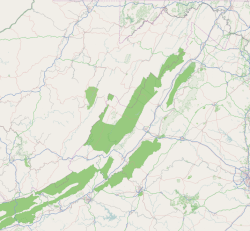

Radford in Virginia | |

| Coordinates: 37°7′39″N 80°34′10″W / 37.12750°N 80.56944°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1887 |

| Named for | John B. Radford |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | David Horton |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.01 sq mi (25.92 km2) |

| • Land | 9.68 sq mi (25.06 km2) |

| • Water | 0.33 sq mi (0.86 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,103 ft (641 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 16,070 |

| • Density | 1,600/sq mi (620/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 24141–24143 |

| Area code | 540 |

| FIPS code | 51-65392[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1500073[3] |

| Website | http://www.radfordva.gov |

Radford (formerly Lovely Mount, Central City, English Ferry and Ingle's Ferry) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. As of 2020, the population was 16,070 by the United States Census Bureau.[4] For statistical purposes, the Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Radford with neighboring Montgomery County.

Radford is included in the Blacksburg–Christiansburg metropolitan area.

Radford is the home of Radford University. Despite its name, the Radford Arsenal, historically a major employer of city residents, is in neighboring Pulaski and Montgomery counties. Radford City has four schools: McHarg Elementary, Belle Heth Elementary, Dalton Intermediate, and Radford High School.

History

[edit]Radford was named for Dr. John B. Radford.[5] Dr. Radford's home Arnheim was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002.[6] Radford was originally a small village of people that gathered near the New River, which was a major draw to travelers for fresh water and food while traveling west. The town's population grew rapidly after 1854 when the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was built nearby. A large depot was placed at Lovely Mount because of its strategic positioning between the eastern and western parts of the state. The actual station was not on Lovely Mountain, located on the southwestern side of town, but Lovely Mount was a known mountain and naming the station this would help people to remember the location of the depot. The Railroad Depot caused the population of Radford to boom. It also caused a major increase in the amount of trade and business in the area. Radford became a railroad town. The original name for Radford was Lovely Mount because of the location of the depot; the name was changed in 1891 to Radford. Radford, or at least the train station area, was called Central Depot because of its central location halfway between Lynchburg and Bristol, Virginia, on the original railroad, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad (later the Norfolk and Western Railway). The names "Ingle's Ferry" or "English Ferry" were derived from Ingles Ferry over the New River, just West of the town.

From 1900 to 1930, many companies came to Radford, including an ice company, a creamery, milling companies, piping, and preserving plants. In 1913, Radford was selected to become home to Radford State Normal School, a women's college. The school would later, in 1924, become Radford College and then in 1979 would be renamed Radford University. The presence of a college brought even more attention to Radford, causing even more population growth. In 1940–1941 the US Military decided to build a manufacturing plant for gunpowder and other ammunition needed by the military. Thus the Radford Army Ammunition Plant, or the "Arsenal" as it would come to be called, joined the railroad and Lynchburg Foundry as major employers creating a huge influx in population. Many families moved to the area. Housing for the Arsenal was built in specific areas of town and these neighborhoods still exist today; Monroe Terrace, Radford Village, and Sunset Village. Today these are Radford's main residential neighborhoods. The railroad ceased passenger service through Radford 1971 as personal transportation moved to the fairly new interstate highway system and the airways. However, the railroad route through Radford is still a major component of Norfolk Southern Railway's Roanoke to Bristol route. But, Radford no longer needed the railroad passenger service to survive.

The James Charlton Farm, Ingles Bottom Archeological Sites, and Ingles Ferry are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[6]

Although a majority of Radford voters supported Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden in the elections of 2008, 2012, 2016 and 2020, during the 2012 campaign the city was the site of the so-called Crumb and Get It bakery incident, in which a bakery owner declined to host a campaign event for then-Vice President Joe Biden, citing political differences.[7] The incident sparked significant media coverage and a surge in business for the bakery.[7]

Glencoe Museum

[edit]Glencoe | |

Glencoe, October 2013 | |

| Location | First St., Radford, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 2.1 acres (0.85 ha) |

| Built | 1875 |

| Architectural style | Second Empire |

| NRHP reference No. | 00001439[6] |

| VLR No. | 126-0045 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 22, 2000 |

| Designated VLR | September 15, 1999[8] |

Glencoe Museum is located in west downtown Radford overlooking the New River.[9] The house was built in 1870 in the 19th century Victorian style, specifically Second Empire, and serves as a home for many artifacts concerning the beginnings of Radford. It was the postbellum home of Confederate Brigadier General Gabriel C. Wharton. It is a large, two-story, five-bay, brick dwelling, and originally had quite extensive grounds. The original house had a barn, chicken coop, smoke house, and an ice house. The name Glencoe is thought to be inspired by Anne Wharton's ancestry. Her family was originally from Scotland. The house didn't appear on Radford's tax records until 1876, it took a very long time to build a house of its size and grandeur in the 1800s. The house was kept in the family till 1996 when, after being deserted for 30 years, the house was given to the city of Radford.[10]

The house and grounds were donated by the Kollmorgen Motion Technology Group. The house was converted into a museum to show off pieces of history found in Radford. There are many Native American artifacts in the museum that help us understand the New River's importance to the Native American culture and way of life. In Glencoe, a person can find some of the original blueprints for the city and pictures of Radford from the past. There is also Local Sports History exhibit and an exhibit on how the river impacted life in Radford. The New River Exhibit also includes a lot of information on ferries, steamboats, and other modes of transportation used on the river. Glencoe Museum is a very popular attraction for school field trips and visitors who are trying to find out more about Radford.

It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.[6]

Local attractions

[edit]Radford has five parks: Bisset Park, Wildwood Park, Riverview Park, Sunset Park, and Sisson Park. Radford also has the historic antebellum period Glencoe Museum, a local farmer's market and one movie theater.

Sunset Park is located in the center of the west end of Radford. Riverview is used mainly for soccer practices, and like its name suggests is also located on the New River and in the west end of Radford. Wildwood Park is a wildlife and plant reserve for the city. Sisson Park, like Sunset Park, is located in the center of the west end of Radford. Sisson Park also accommodates Joe Hodge Field, a baseball/softball field, mainly used for little league practices and games.[11]

Bisset Park

[edit]Bisset Park is the largest of the four parks, located on the New River, it stretches 57 acres (23 ha). Bisset Park was named for David Bisset, a major contributor and overseer of parks and recreation in Radford. Bisset Park is located in the center of town across from Wildwood Park. It features three picnic shelters, a gazebo, tennis courts, and open fields mainly used for little league soccer. The Riverway Trail is a 3.5 mile paved biking and walking path that can be accessed from Bissett Park. From there the trail extends to the east along the New River and to the south into Wildwood Park. A Civil War Trails marker can be found at the westernmost end of the park, where the foundation of a bridge burned down during the Battle of New River Bridge can be seen.[12]

Wildwood Park

[edit]Wildwood Park is a 50-acre wooded ravine in the center of town, with a paved bikeway along a stream at the bottom of two forested hillsides crisscrossed by hiking trails.[5] It became the city's first public park in 1929,[13] and was narrowly rescued from a highway-bypass plan in 1998 with the formation of a "Pathways for Radford" group[14][15] seeking city support, leading to a development plan.[16] The park falls along the original boundary between the former towns of East Radford, home of Radford University, and the traditionally more industrial West Radford. The towns were joined with the bridging of Connelly's Run by the city's East and West Main Street.[13] The park's bikeway extends through a culvert tunnel beneath Main Street, connecting to the city's Bissett Park along the New River. Wildwood Park includes a public restroom and a roofed pavilion with meeting or picnic tables. The park is used by both Radford University and Radford High School for biology classes as well as summer nature lectures for the public. Students perform animal, plant, and stream tests, tree population counts, clean stream testing (for federal use), and observation of wildlife, Monarch butterflies, and spring wildflowers.[17] The well-documented variety of flowers is especially attractive to visitors.[18] Wildlife include many native birds as well as deer, raccoons, opossums, skunks, and groundhogs. The western slope includes Adams Cave, a limestone cave used for saltpeter during the Civil War; the cave entrance is now gated and locked. A shallow stream, Connelly's Run, flows through the park and provides great crayfish hunting for children during the summer months. A culvert carries its waters under Main Street to the New River in Bisset Park. Connelly's Run fed a city swimming pool for 45 years, but the pool was closed and filled-in when faced with the prospect of racial integration in 1965.[19]

Geography

[edit]Radford is located at 37°7′39″N 80°34′10″W / 37.12750°N 80.56944°W (37.127585, −80.569523).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.2 square miles (26.4 km2), of which 9.9 square miles (25.6 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.8 km2) (3.3%) is water.[20] The New River runs along the southwestern, western and northern edge of the city.

Weather and climate history

[edit]

The worst river flooding in Radford's recorded history occurred on August 14, 1940, with a slow-moving tropical depression. The 1940 hurricane season produced eight storms, four of which were hurricanes. Around August 5 of that year, a tropical storm was detected along the northern Leeward Islands in the West Indies. The storm brought wind gusts of 44 mph to San Juan, Puerto Rico, as it moved northwestward. By August 6 it began a turn to the north while producing rough seas in the southeastern Bahamas. Four days later on August 10 the S.S. Maine off the southeast coast measured hurricane-force winds and the storm began movement again toward the northwest. The storm made landfall as a category 1 hurricane on August 11 at approximately 4 PM near Beaufort, South Carolina (along the SC/GA border). Winds reached 73 mph in nearby Savannah, Georgia.

As the Georgia – South Carolina hurricane of 1940 moved inland, record rainfall amounts were observed from South Carolina north through the Smoky Mountains and into southwest and central Virginia. The storm meandered along the Cumberland Plateau region as rain began falling in Virginia on August 13. The mountainous terrain coupled with extremely slow movement from the now tropical depression produced tremendous amounts of rain. Copper Hill in Floyd County, Virginia, received the highest rainfall in the state: 17.03 inches.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) stream gauge across the New River (Kanawha River) from Bisset Park measured an all-time record height of 35 feet 11.5 inches which is nearly 22 feet above what is considered flood stage. Residents in low-lying areas were forced to evacuate their homes and both the former Burlington Mills and the Lynchburg Foundry manufacturing plants were shut down because of high water. The road leading from Radford into Pulaski County towards Claytor Lake Dam was inundated and impassable. Thankfully, no deaths were reported across southwest Virginia, but several million dollars worth of damage occurred (1940 USD).

On October 18, 2011, a sign recognizing the historic flooding was dedicated in Bisset Park near downtown Radford. The sign was donated by local resident Anthony Phillips, a hydrometeorologist from Snowville, Virginia, and installation was sponsored by the National Weather Service and the United States Geological Survey through the High Water Mark (HWM) Project.[21][22] The project helps raise awareness of flood risk by installing high-water mark signs in prominent locations within communities that have experienced severe flooding.[23]

Adjacent counties

[edit]- Pulaski County, Virginia – west

- Montgomery County, Virginia – east

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 2,060 | — | |

| 1900 | 3,344 | 62.3% | |

| 1910 | 4,202 | 25.7% | |

| 1920 | 4,627 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 6,227 | 34.6% | |

| 1940 | 6,990 | 12.3% | |

| 1950 | 9,026 | 29.1% | |

| 1960 | 9,371 | 3.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,596 | 23.7% | |

| 1980 | 13,225 | 14.0% | |

| 1990 | 15,940 | 20.5% | |

| 2000 | 15,859 | −0.5% | |

| 2010 | 16,408 | 3.5% | |

| 2020 | 16,070 | −2.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[24] 1790–1960[25] 1900–1990[26] 1990–2000[27] 2010[28] 2020[29] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[28] | Pop 2020[29] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 14,075 | 12,006 | 85.78% | 74.71% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 1,262 | 2,125 | 7.69% | 13.22% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 30 | 30 | 0.18% | 0.19% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 251 | 210 | 1.53% | 1.31% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 5 | 0 | 0.03% | 0.00% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 23 | 269 | 0.14% | 1.67% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 377 | 665 | 2.30% | 4.14% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 385 | 765 | 2.35% | 4.75% |

| Total | 16,408 | 16,070 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2000 Census

[edit]As of the census[30] of 2000, there were 15,859 people, 5,809 households, and 2,643 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,615.2 people per square mile (623.6 people/km2). There were 6,137 housing units at an average density of 625.0 units per square mile (241.3 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.21% White, 8.10% African American, 0.25% Native American, 1.43% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.49% from other races, and 1.51% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.16% of the population.

There were 5,809 households, out of which 18.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.9% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.5% were non-families. 32.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.78.

The age distribution, which is strongly influenced by Radford University, is: 12.9% under the age of 18, 44.0% from 18 to 24, 19.6% from 25 to 44, 14.3% from 45 to 64, and 9.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 23 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $24,654, and the median income for a family was $46,332. Males had a median income of $33,045 versus $22,298 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,289. About 6.9% of families and 31.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.8% of those under age 18 and 9.4% of those age 65 or over.

Local sports accomplishments

[edit]- From 1946 to 1950, Radford hosted its first and only Professional Baseball team, The Radford Rockets, who played as members of the Blue Ridge League.[9]

- John Dobbins was the 1st Black Football player for Virginia Tech.[9]

- Radford High School has won 36 VHSL State Titles.[31]

- Radford's 1971 and 1972 high school football teams were undefeated and won over 26 straight games. The Bobcats won the AA state title 2 years in a row and they were considered one of the top high school football teams in the nation in the early 1970s.[according to whom?]

- Virginia Tech Head Football Coach Frank Beamer was an assistant coach for the 1971 AA State Championship Radford Bobcats Football Team.[32]

- Norman G. Lineburg is legendary in Virginia for coaching the Radford Bobcats from 1970 to 2006. He retired from coaching football after the 2006 season with 315 wins. Lineburg has the second most wins in VHSL football history behind legendary Hampton coach Mike Smith.[33]

- Former Radford High School standout Darris Nichols was a basketball player for the West Virginia Mountaineers. Nichols is famous in Mountaineer-lore for hitting the game-winning three-point shot that sent the Mountaineers to the NIT Championship game in 2007. He also holds the school record for the most career games played and most tournament games played all-time, tied for the school record for the most all-time postseason tournament games played, and the NCAA record for playing 141 games without fouling out.

Radford High School Athletic State Titles: 2022 Class A Boys' Outdoor Track and Field, 2017 Class 2A Boys Swimming 2013 Class A Boys' Outdoor Track and Field, 2013 Class A Boys' Basketball, 2012 Class A Boys' Cross Country, 2011 Class A Boys' Basketball, 2011 Class A Girls' Basketball, 2009 Class A Boys' Basketball, 2008 Class A Boys' Soccer, 2007 Class A Girls' Soccer, 2007 Class A Boys' Soccer, 2007 Class A Boys' Cross Country, 2005 Class A Girls' Basketball, 2002 Class A Girls' Tennis, 2001 Class A Girls' Tennis, 2000 Class A Girls' Tennis, 1999 Class A Girls' Tennis, 1998 Class A Wrestling, 1998 Class A Girls' Tennis, 1998 Class A Boys' Tennis, 1998 Class A Boys' Track, 1990 Class AA Girls' Track, 1989 Class AA Girls' Track, 1988 Class AA Girls' Basketball, 1988 Class AA Girls' Tennis, 1985 Class AA Girls' Tennis, 1984 Class AA Girls' volleyball, 1984 Class AA Girls' Basketball, 1983 Class AA Girls' Basketball, 1972 Class AA Football, 1972 Class AA Boys' Outdoor Track, 1972 Class AA Boys' Indoor Track, 1971 Class AA Football, 1963 Class AA Boys' Tennis, 1949 Class AA Boys' Basketball.

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Radford has a marine west coast climate, abbreviated "Cfb" on climate maps.[34]

Notable people

[edit]- Richard Harding Poff, US Representative and Senior Justice of VA Supreme Court. Richard Nixon's choice for nomination to the supreme court, he withdrew his name before the nomination reached the senate.

- The Gregory Brothers, musicians, comedians

- John Dalton, former Virginia Governor

- James Hoge Tyler, former Virginia Governor

- James Clinton Turk, United States District Judge and Minority Leader of State Senate

- Theodore Roosevelt Dalton, United States District Judge and two time Republican candidate for Governor

- Glen E. Conrad, United States District Judge

- Scott Long, human rights activist

- Mike Williams, Major League Baseball relief pitcher

- John Ripley, United States Marine Corps Colonel and recipient of the Navy Cross

- Kevin Hartman, Major League Soccer goalkeeper

- Margaret Skeete (1878–1994), oldest living American

- Paul Washer, Christian missionary and evangelist

- Seka (actress), actress, radio talk show host, and author

- Mike Young (basketball), Virginia Tech Hokies Men's Head Basketball Coach

Politics

[edit]As reflected in the table below, Radford has leaned Democratic in presidential elections, but citizens have rarely given a candidate 60 percent of their vote.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 2,786 | 44.08% | 3,358 | 53.13% | 176 | 2.78% |

| 2016 | 2,638 | 43.37% | 2,925 | 48.09% | 519 | 8.53% |

| 2012 | 2,520 | 46.68% | 2,732 | 50.60% | 147 | 2.72% |

| 2008 | 2,418 | 44.54% | 2,930 | 53.97% | 81 | 1.49% |

| 2004 | 2,564 | 52.92% | 2,244 | 46.32% | 37 | 0.76% |

| 2000 | 2,190 | 49.24% | 2,063 | 46.38% | 195 | 4.38% |

| 1996 | 1,742 | 40.67% | 2,113 | 49.33% | 428 | 9.99% |

| 1992 | 1,996 | 41.71% | 2,183 | 45.62% | 606 | 12.66% |

| 1988 | 2,481 | 56.84% | 1,855 | 42.50% | 29 | 0.66% |

| 1984 | 2,855 | 61.15% | 1,781 | 38.15% | 33 | 0.71% |

| 1980 | 1,964 | 44.01% | 2,225 | 49.85% | 274 | 6.14% |

| 1976 | 1,844 | 44.74% | 2,240 | 54.34% | 38 | 0.92% |

| 1972 | 2,577 | 68.68% | 1,121 | 29.88% | 54 | 1.44% |

| 1968 | 2,077 | 55.40% | 1,206 | 32.17% | 466 | 12.43% |

| 1964 | 1,505 | 44.82% | 1,850 | 55.09% | 3 | 0.09% |

| 1960 | 1,663 | 57.11% | 1,240 | 42.58% | 9 | 0.31% |

| 1956 | 1,910 | 62.46% | 1,118 | 36.56% | 30 | 0.98% |

| 1952 | 1,523 | 57.73% | 1,108 | 42.00% | 7 | 0.27% |

| 1948 | 850 | 48.16% | 826 | 46.80% | 89 | 5.04% |

| 1944 | 597 | 41.95% | 824 | 57.91% | 2 | 0.14% |

| 1940 | 417 | 34.29% | 793 | 65.21% | 6 | 0.49% |

| 1936 | 421 | 39.05% | 650 | 60.30% | 7 | 0.65% |

| 1932 | 341 | 37.51% | 542 | 59.63% | 26 | 2.86% |

| 1928 | 524 | 58.42% | 373 | 41.58% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 314 | 38.91% | 394 | 48.82% | 99 | 12.27% |

| 1920 | 245 | 37.12% | 402 | 60.91% | 13 | 1.97% |

| 1916 | 115 | 35.17% | 206 | 63.00% | 6 | 1.83% |

| 1912 | 36 | 10.98% | 185 | 56.40% | 107 | 32.62% |

| 1908 | 141 | 39.94% | 204 | 57.79% | 8 | 2.27% |

| 1904 | 100 | 34.25% | 184 | 63.01% | 8 | 2.74% |

| 1900 | 197 | 42.92% | 257 | 55.99% | 5 | 1.09% |

| 1896 | 309 | 43.58% | 372 | 52.47% | 28 | 3.95% |

| 1892 | 185 | 23.33% | 591 | 74.53% | 17 | 2.14% |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Radford city, Radford city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ a b HISTORY « City of Radford." City of Radford. Web. July 24, 2010.<"Radford City". Archived from the original on November 30, 2004. Retrieved December 29, 2004.>.

- ^ a b c d "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Adams, Mason (August 15, 2012). "Radford bakery that turned Biden away sells out of 'freedom cookies'". The Roanoke Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018.

- ^ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c Glencoe Museum (July 24, 2010). "History". Radford MIRA Project.

- ^ Gibson Worsham (June 1999). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Glencoe" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. and Accompanying photo

- ^ "Sisson Park / Joe Hodge Field". Radford, VA. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Bisset Park". Radford, VA. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Wildwood Park: Yesterday". Wildwood Park (2008 page, via Internet Archive). Radford Public Library. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Angelone, Anita (March 5, 2021). "PLACES THAT CONNECT: Wildwood Park, City of Radford". Virginia Outdoors Foundation. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "Pathways for Radford". Pathways for Radford. Internet Archive. Archived from the original on July 2, 2007. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "Wildwood Park: Tomorrow (Internet Archive copy of 2008 page)". Wildwood Park. Radford Public Library. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "Wildwood Park: Today". Wildwood Park (Internet Archive copy of 2008 page). Radford Public Library. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Schoenholtz, Gloria. "Wildwood Park". Virginia Wildflowers. Virginia Wildflowers Blog. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Alvis-Banks, Donna (July 9, 2004). "Only memories remain of Radford's Wildwood pool". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Radford City and Town of Snowville Unveil High Water Mark Signs. ABC 13 News. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Radford high-water sign to be unveiled. The Roanoke Times. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ NWS High Water Mark Signs. NOAA Office of Climate, Water, and Weather Services. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing from 1790". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Radford city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Radford city, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "State Titles". rcps.org. January 24, 2012.

- ^ "Frank Beamer | Head Football Coach". hokiesports.com. January 24, 2012.

- ^ "VHSL Record Book (archived copy)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2012.. p. 38. VHSL Record Book.

- ^ Climate Summary for Radford, Virginia

- ^ Dave Leip. "Atlas of U.S. Elections".

External links

[edit]- Radford, Virginia

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia

- Houses completed in 1870

- Second Empire architecture in Virginia

- Cities in Virginia

- Blacksburg–Christiansburg metropolitan area

- U.S. Route 11

- National Register of Historic Places in Radford, Virginia

- Virginia populated places on the New River