Religious censorship

| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

Religious censorship is a form of censorship where freedom of expression is controlled or limited using religious authority or on the basis of the teachings of the religion. This form of censorship has a long history and is practiced in many societies and by many religions. Examples include the Edict of Compiègne, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of prohibited books) and the condemnation of Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses by Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

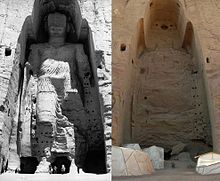

Religious censorship can also take form in the destruction of monuments and texts that contradict or conflict with the religion practiced by the oppressors, such as attempts to censor the Harry Potter book series.[1] Destruction of historic places is another form of religious censorship. One cited incident of religious censorship was the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan statues in Afghanistan by radical Islamists as part of their religious goal of oppressing another religion.[2]

Overview

[edit]Religious censorship is defined as the act of suppressing views that are contrary of those of an organized religion. It is usually performed on the grounds of blasphemy, heresy, sacrilege or impiety – the censored work being viewed as obscene, challenging a dogma, or violating a religious taboo. Defending against these charges is often difficult as some religious traditions permit only the religious authorities (clergy) to interpret doctrine and the interpretation is usually dogmatic. For instance, the Catholic Church banned hundreds of books on such grounds and maintained the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of prohibited books), most of which were writings that the Church's Holy Office had deemed dangerous, until the Index's abolishment in 1965.

In Christianity

[edit]The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 changed the nature of book publishing.[3] As of the 16th century, in most European countries both the church and governments attempted to regulate and control printing. Governments established controls over printers across Europe, requiring them to have official licenses to trade and produce books.[4][5] In 1557 the English Crown aimed to stem the flow of dissent by chartering the Stationers' Company. The right to print was restricted to the two universities (Oxford and Cambridge) and the 21 existing printers in the City of London. In France, the 1551 Edict of Châteaubriant included provisions for unpacking and inspecting all books brought into France.[6][7] The 1557 Edict of Compiègne applied the death penalty to heretics and resulted in the burning of a noblewoman at the stake.[8]

A first version of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum ("List of Prohibited Books") was promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1559, and multiple revisions were made to it over the years.

Some works named in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum are the writings of Desiderius Erasmus, a Catholic scholar who argued that the Comma Johanneum was probably forged and De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, a treatise by Nicolaus Copernicus arguing for a heliocentric orbit of the earth, both works that at the time contradicted the Church's official stance on particular issues.

The final (20th) edition appeared in 1948, and it was formally abolished on 14 June 1966 by Pope Paul VI.[9][10] However, the moral obligation of the Index was not abolished, according to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[11] Furthermore, the 1983 Code of Canon Law states that bishops have the duty and right to review material concerning faith or morals before it may be published.[12]

In 1992 José Saramago's "The Gospel According to Jesus Christ" entry in the Aristeion European Literary Prize was blocked by the Portuguese Under Secretary of State for Culture due to pressures from the Catholic Church.[13]

In Islamic societies

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

Although nothing in the Qur'an explicitly imposes censorship, similar methodology has been carried out under Islamic theocracies, such as the fatwa (religious judgment) against The Satanic Verses (a novel), ordering that the author be executed for blasphemy.

Some Islamic societies have religious police, who seize banned consumer products and media regarded as un-Islamic, such as CDs/DVDs of various Western musical groups, television shows and film.[14] In Saudi Arabia, religious police actively prevent the practice or proselytizing of non-Islamic religions within Arabia, where they are banned.[14] This included the ban of the film, The Passion of the Christ.

Examples of Muslim censorship:

- Depictions of Muhammad have inspired considerable controversy and censorship in the 2000s, including the adjacent image.

- The Jewel of Medina, a work of historical fiction censored pre-publication.

In Judaism

[edit]Throughout the history of the publishing of Jewish books, various works have been censored or banned. These can be divided into two main categories: Censorship by a non-Jewish government, and self-censorship. Self-censorship could be done either by the author himself, or by the publisher, out of fear from the gentiles or public reaction. Another important distinction that has to be made is between the censorship which existed already on manuscripts, before the printing press was invented, and the more official censorship after the printing press was invented.

Non-Jewish government censorship

[edit]Many studies have been written on censorship and its influence on the publishing of Jewish books. For example, studies have appeared on the censorship of Jewish books when they were first starting to be published, in Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth century. Other studies have been written on the censorship of the Czarist government in Russia in the nineteenth century.

Many of the "official" Christian government censors of Jewish books were Jewish apostates. The main reason for this was due to their knowledge of Hebrew, especially Rabbinic Hebrew.

In Czarist Russia in the nineteenth century, it was decreed that Jewish books could only be published in two cities, Vilnius and Zhitomir.

Censorship by Jewish religious authorities

[edit]The Mishnah (Sanhedrin 10:1) prohibits the reading of extra-biblical books (ספרים חיצונים). The Talmud explains this to mean the book of Ben Sirah (Sirach). In the early thirteenth century the philosophical book The Guide for the Perplexed by Maimonides was prohibited to be read until one was older by some French and Spanish Jewish leaders, because of the perceived danger of philosophy. Philosophy was prohibited to be learned until the age of forty. The same restriction was later applied to Kabbalah, in the fifteenth century. In the 1720s, the kabbalistic works of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato were banned by religious leaders. In the 1690s, the book Pri Chadash was banned in Egypt for arguing on earlier authorities.[16]

In the modern era, when government censorship of Jewish books is uncommon, books are mainly self-censored, or banned by Orthodox Jewish religious authorities. Marc Shapiro points out that not all books considered heretical by Orthodox Jews are banned; only those books on which there is a risk that Orthodox Jews may read them are banned.[17] Some examples:

- The Reconstructionist Siddur (1945), revised by Mordecai Kaplan.

- Torah Study: A Survey of Classic Sources on Timely Issues (1990), by Rabbi Leo Levi, was banned by Rabbi Elazar Shach. It was banned because it discussed the value of studying subjects other than Torah.

- My Uncle The Netziv (1988), an excerpt of the book Mekor Baruch by Rabbi Baruch Epstein, was banned by anonymous Rabbis in Lakewood, New Jersey. It was banned because it was perceived to have said unflattering things about the Netziv.[18]

- HaGaon (Hebrew, 2002), a biography of the Vilna Gaon, by Dov Eliach, was banned by Chassidic leaders for its attacks against Chassidus.[19]

- The Science of Torah (2001), by Rabbi Natan Slifkin, was banned by Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv and others. It was banned because it explained how the theory of evolution can fit with Judaism; evolution is opposed by many authorities. Slifkin's books Mysterious Creatures (2003) and The Camel, the Hare and the Hyrax (2004) were also banned, because they brought down opinions that Chazal could be incorrect in their scientific knowledge.

- Making of a Godol (2002), by Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky, was banned by Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv and other Orthodox Jewish authorities because of its sometimes unflattering portrayals of Jewish leaders.

- The Dignity of Difference (2002), by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, was banned by Rabbi Elayshiv and others. It was banned because it was perceived to equate Judaism with other religions.

- One People, Two Worlds: A Reform rabbi and an Orthodox rabbi explore the issues that divide them (2003) by Reform Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch and Orthodox Rabbi Yosef Reinman, was banned by the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudath Israel of America and the heads of Beth Medrash Govoha, Lakewood, New Jersey.

- Kosher Jesus (2012), by Rabbi Shmuley Boteach, was banned by Chabad rabbi Jacob Immanuel Schochet, who labelled the book as heretical and stated that it "poses a tremendous risk to the Jewish community," and that "I have never read a book, let alone one authored by a purported frum Jew, that does more to enhance the evangelical missionary message and agenda than the aforementioned book".[20]

In the Baháʼí Faith

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith has a requirement that Baháʼí authors should seek review of their works by the National Spiritual Assembly of the country in which it will be printed. The requirement was initiated by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and intended to sunset when the religion grows in numbers. The publication review requirement does not apply to most online content or local promotional material. According to the Universal House of Justice, the highest governing body of the religion,

The purpose of review is to protect the Faith against misrepresentation by its own followers at this early stage of its existence when comparatively few people have any knowledge of it. An erroneous presentation of the Teachings by a Baháʼí who is accounted a scholar, in a scholarly journal, would by that very fact, do far more harm than an erroneous presentation made by an obscure Baháʼí author with no pretensions to scholarship.[21]

The review requirement has been criticized by a few academic Baháʼís as censorship. Juan Cole, professor of history at the University of Michigana, had conflicts over the issue and withdrew his membership as a Baháʼí, claiming that it "has provoked many conflicts between Baháʼí officials and writers over the years."[22] Denis MacEoin similarly resigned his membership and said that the review stifled research in Baháʼí studies.[23] Moojan Momen, another academic in the field of Baháʼí studies who has called MacEoin and Cole "apostates", disagrees and states that "there is no more 'censorship' involved in this process than with any other academic journal."[24]

In Buddhism

[edit]Art was censored extensively under the military government in Myanmar at the end of the 20th century. Nudity was not permitted, and art was also censored when it was deemed that Buddhism was portrayed in a non-typical fashion. Following the governmental transition in 2011, relevant censorship laws remained in effect but were enforced more loosely.[25]

In 2015, the film Arbat was banned in Thailand due to its portrayal of Buddhist monks. Criticisms included a scene involving kissing and another in which a monk engaged in drug use.[26]

See also

[edit]- Aniconism

- Discrimination against atheists

- Iconoclasm

- Religion and sexuality

- Religious intolerance

- Religious offense

- Theocracy

- Censorship in India

- Ryan McCourt

References

[edit]- ^ Bald, Margaret; Wachsberger, Ken (2006). Literature Suppressed on Religious Grounds (Revised ed.). Facts on File. ISBN 0816062692.

- ^ "Toppling monuments, erasing history". The Washington Post. 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017.

- ^ McLuhan, Marshall (1962), The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1st ed.), University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9 p. 124

- ^ MacQueen, Hector L; Charlotte Waelde; Graeme T Laurie (2007). Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-926339-4.

- ^ de Sola Pool, Ithiel (1983). Technologies of freedom. Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-87233-2.

- ^ The Rabelais encyclopedia by Elizabeth A. Chesney 2004 ISBN 0-313-31034-3 pp. 31–32

- ^ The printing press as an agent of change by Elizabeth L. Eisenstein 1980 ISBN 0-521-29955-1 p. 328

- ^ Robert Jean Knecht, The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France: 1483–1610 2001, ISBN 0-631-22729-6 p. 241

- ^ "Galileo and Books". Archived from the original on 7 March 2012.

- ^ "Index Librorum Prohibitorum | Roman Catholicism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Haec S. Congregatio pro Doctrina Fidei, facto verbo cum Beatissimo Patre, nuntiat Indicem suum vigorem moralem servare, quatenus Christifidelium conscientiam docet, ut ab illis scriptis, ipso iure naturali exigente, caveant, quae fidem ac bonos mores in discrimen adducere possint; eundem tamen non-amplius vim legis ecclesiasticae habere cum adiectis censuris" (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 58 (1966), p. 445). Cf. "Italian text published, together with the Latin" (PDF). L'Osservatore Romano. 15 June 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Can. 823 §1. In order to preserve the integrity of the truths of faith and morals, the pastors of the Church have the duty and right to be watchful so that no harm is done to the faith or morals of the Christian faithful through writings or the use of instruments of social communication. They also have the duty and right to demand that writings to be published by the Christian faithful which touch upon faith or morals be submitted to their judgment and have the duty and right to condemn writings which harm correct faith or good morals. §2. Bishops, individually or gathered in particular councils or conferences of bishops, have the duty and right mentioned in §1 with regard to the Christian faithful entrusted to their care; the supreme authority of the Church, however, has this duty and right with regard to the entire people of God. Can. 824 §1. Unless it is established otherwise, the local ordinary whose permission or approval to publish books must be sought according to the canons of this title is the proper local ordinary of the author or the ordinary of the place where the books are published. §2. Those things established regarding books in the canons of this title must be applied to any writings whatsoever which are destined for public distribution, unless it is otherwise evident." 1983 Code of Canon Law, Instruments of Social Communion and Books in Particular (Cann. 822–832)

- ^ Eberstadt, Fernanda (18 June 2010). "José Saramago, Nobel Prize-Winning Portuguese Writer, Dies at 87". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Saudi Arabia Catholic priest arrested and expelled from Riyadh". Asia News. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015.

- ^ "Le Prophète Mahomet". L'art du livre arabe. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ "The Pri Chadash – Honored In Amsterdam, Scorned In Egypt, Fulfilled In Yerushalayim". The Jewish Eye. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Shapiro, Marc B. "The Edah Journal – Of Books And Bans" (PDF). www.edah.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Schacter, Jacob J. "Haskalah, Secular Studies and the Close of the Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1892" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Tradition Seforim Blog : HaGaon". Seforim.traditiononline.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Boswell, Randy (30 January 2012). "'Kosher Jesus' book ignites skirmish between Jewish scholars". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012.

- ^ Helen Hornby (ed.). Lights of Guidance. Baháʼí Library Online. p. 101. Archived from the original on 3 September 2022.

- ^ Cole, Juan R.I. (June 1998). "The Baha'i (sic) Faith in America as Panopticon, 1963–1997". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 37 (2). Wiley-Blackwell: 234–248. doi:10.2307/1387523. JSTOR 1387523. OCLC 781517232. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2016 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ^ MacEoin, Denis (1990). "The crisis in Bábí and Baháʼí studies: part of a wider crisis in academic freedom?" (PDF). British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 17 (1). British Society for Middle Eastern Studies: 55–61. doi:10.1080/13530199008705506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2021.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (2007). "Marginality and Apostasy in the Baháʼí Community". Religion. 37 (37:3). Routledge: 187–209. doi:10.1016/j.religion.2007.06.008. OCLC 186359943. S2CID 55630282. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022.

- ^ Carlson, Melissa (March 2016). "Painting as cipher: censorship of the visual arts in post-1988 Myanmar". Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia: 145.

- ^ "Thailand bans film over depictions of Buddhist monks". Al Jazeera America. 13 October 2015. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

External links

[edit]- Articles about censorship by religion in the field of music on Freemuse.org – the world's largest database on music censorship

- Jewish Encyclopedia entry "Censorship of Hebrew Books"