Jannah

In Islam, Jannah (Arabic: جَنَّةٍ, romanized: janna, pl. جَنّٰت jannāt, lit. 'garden')[1] is the final and permanent abode of the righteous.[2] According to one count, the word appears 147 times in the Qur'an.[3] Belief in the afterlife is one of the six articles of faith in Sunni and Twelver Shi'ism and is a place in which "believers" (Mumin) will enjoy pleasure, while the unbelievers (Kafir) will suffer in Jahannam.[4] Both Jannah and Jahannam are believed to have several levels. In the case of Jannah, the higher levels are more desirable, and in the case of Jahannam, the lower levels have a higher level of punishments — in Jannah the higher the prestige and pleasure, in Jahannam the severity of the suffering.[5]: 131-133 The afterlife experiences are described as physical, psychic and spiritual.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Jannah is described with physical pleasures such as gardens, beautiful houris, wine that has no aftereffects, and "divine pleasure".[6] Their reward of pleasure will vary according to the righteousness of the person.[7][8] The characteristics of Jannah often have direct parallels with those of Jahannam. The pleasure and delights of Jannah described in the Qu'ran, are matched by the excruciating pain and horror of Jahannam.[9][10]

| Islamic eschatology |

|---|

| Islam portal |

Jannah is also referred to as the abode of Adam and Eve before their expulsion.[5]: 165 Most Muslims hold that Jannah and Jahannam co-exist with the temporal world, rather than being created after Judgement Day.[11] Humans may not pass the boundaries to the afterlife, but it may interact with the temporal world of humans.

According to some Islamic teachings, there are two categories of the people of heaven: those who go directly to it and those who enter it after enduring some torment in hell; Also, the people of hell are of two categories: those who stay there temporarily and those who stay there forever.[citation needed]

Terminology

[edit]Jannah is found frequently in the Qur'an (2:30, 78:12) and often translated as "Heaven" in the sense of an abode in which believers are rewarded in afterlife. Another word, سماء samāʾ (usually pl. samāwāt) is also found frequently in the Quran and translated as "heaven" but in the sense of the sky above or the celestial sphere.[12][13] (It is often used in the phrase as-samawat wal-ard ٱلسَّمَٰوَٰتِ وَٱلۡأَرۡضِ "the heavens and the earth", an example being Qu'ran 38:10.) The Qu'ran describes both samāʾ and jannah as being above this world.

Jannah is also frequently translated as "paradise", but another term with a more direct connection to that term is also found, Firdaus (Arabic: فردوس), the literal term meaning paradise, which was borrowed from the Persian word Pardis (Persian: پردیس), which is also the source of the English word "paradise". Firdaus is used in Qu'ran 18:107 and 23:11[14] and also designates the highest level of heaven.[15]

In contrast to Jannah, the words Jahannam, an-Nār, jaheem, saqar, and other terms are used to refer to the concept of hell. There are many Arabic words for both Heaven and Hell that also appear in the Qu'ran and in the Hadith. Most of them have become part of Islamic beliefs.[16]

Jannah is also used as the name of the Garden of Eden in which Adam and Hawa (Eve) dwelt.

Salvation/inhabitants

[edit]

Scholars do not all agree on who will end up in Jannah, and the criteria for whether or not they will. Issues include whether all Muslims, even those who've committed major sins, will end up in Jannah; whether any non-Muslims will go there or all go to Jahannam.

Inhabitants according to Quran

[edit]The Quran specifies the qualities for those allowed to inhabit Jannah (according to Smith and Haddad) as: "those who refrain from doing evil, keep their duty, have faith in God's revelations, do good works, are truthful, penitent, heedful, and contrite of heart, those who feed the needy and orphans and who are prisoners for God's sake."[14] Another source (Sebastian Günther and Todd Lawson) gives as the basic criterion for salvation in the afterlife more detail on articles of faith: the belief in the oneness of God (tawḥīd), angels, revealed books, messengers, as well as repentance to God, and doing good deeds (amal salih).[18]: 51 All these qualities are qualified by the doctrine that ultimately salvation can only be attained through God's judgment.[19]

Jinn, angels, and devils

[edit]The idea that jinn as well as humans could find salvation was widely accepted, based on the Quran (Q.55:74) where the saved are promised maidens "untouched before by either men or jinn" – suggesting to classical scholars al-Suyūṭī and al-Majlisī that jinn also are provided their own kind of houri maidens in paradise.[5]: 140 Like humans, their destiny in the hereafter depends on whether they accept God's guidance. Angels, on the other hand, because they are not subject to desire and so are not subject to temptation, work in paradise serving the "blessed" (humans and jinn) guiding them, officiating marriages, conveying messages, praising them, etc.[5]: 141 The devils cannot return to paradise, because Islamic scripture states that their father, the fallen angel Iblis, was banished, but never suggests that he or his offspring were forgiven or promised to return.[5]: 46 [20](p97)

The eschatological destiny of these creatures is summarized in the prophetic tradition: "One kind of beings will dwell in Paradise, and they are the angels; one kind will dwell in Hell, and they are the demons; and another kind will dwell some in Paradise and some in Hell, and those are the jinn and the humans."[21](p 20)

Salvation of non-Muslims

[edit]Muslim scholars disagree about exact criteria for salvation of Muslim and non-Muslim. Although most agree that Muslims will be finally saved – shahids (martyrs) who die in battle, are expected to enter paradise immediately after death[5]: 40 – non-Muslims are another matter.

Muslim scholars arguing in favor of non-Muslims' being able to enter paradise cite the verse:

"Indeed, the believers, Jews, Christians, and Sabians—whoever ˹truly˺ believes in Allah and the Last Day and does good will have their reward with their Lord. And there will be no fear for them, nor will they grieve."

Those arguing against non-Muslim salvation regard this verse to have applied only until the arrival of Muhammad, after which it was abrogated by another verse:

"Whoever seeks a way other than Islam, it will never be accepted from them, and in the Hereafter they will be among the losers."

Historically, the Ash'ari school of theology was known for having an optimistic perspective on salvation for Muslims,[24] but a very pessimistic view of those who heard about Muhammad and his character, yet rejected him.[25] The Maturidi school also generally agreed that even sinners among Muslims would eventually enter paradise,[5]: 177 but its unclear whether they thought only Muslim would go to Jannah,[26]: 110 or if non-Muslims who understood and obeyed "God's universal law" would be saved also.[26]: 109 The Muʿtazila school held that free will and individual accountability was necessary for Divine justice, thus rejecting the idea of intercession (Shafa'a) by Muhammad on behalf of sinners.[5]: 178 Unlike other schools it believed Jannah and Jahannam would be created only after Judgement Day.[5]: 167–168 Like most Sunni, Shia Islam hold that all Muslims will eventually go to Jannah,[27][28] and like the Ash'ari school, believe heedless and stubborn unbelievers will go to hell, while those ignorant of the truth of Islam but "truthful to their own religion", will not.[29] Modernist scholars Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida rejected the notion that the People of the Book are excluded from Jannah, referring to another verse.[30]

- ˹Divine grace is˺ neither by your wishes nor those of the People of the Book! Whoever commits evil will be rewarded accordingly, and they will find no protector or helper besides Allah. But those who do good—whether male or female—and have faith will enter Paradise and will never be wronged ˹even as much as˺ the speck on a date stone. (Q.4:123–124)[31][30]

Descriptions, details, and organization

[edit]Sources

[edit]Sources on Jannah include the Quran, Islamic traditions, creeds, Quranic commentaries (tafsir) and "other theological writing".[32] "Third Islamic century traditionalists amplified the eschatological material enormously particularly in areas on where "the Quran is relatively silent" about the nature of Jannah.[33] Some of the more popular Sunni manuals of eschatology are Kitāb al-rūḥ of Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīya and al-Durra al-fākhira ft kashf 'ulūm al-ākhira of Abǖ Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī.[33]

Delights

[edit]Inside Jannah, the Quran says the saved "will have whatever they wish for, forever"; (Q.25:16).[18]: 65 [34] Other verses give more specific descriptions of the delights of paradise:

'And whoever is in awe of standing before their Lord will have two Gardens

... ˹Both will be˺ with lush branches.

... In each ˹Garden˺ will be two flowing springs.

... In each will be two types of every fruit.

... Those ˹believers˺ will recline on furnishings lined with rich brocade. And the fruit of both Gardens will hang within reach.

... In both ˹Gardens˺ will be maidens of modest gaze, who no human or jinn has ever touched before.

... Those ˹maidens˺ will be ˹as elegant˺ as rubies and coral.

... Is there any reward for goodness except goodness?

... And below these two ˹Gardens˺ will be two others.

... Both will be dark green.

... In each will be two gushing springs.

... In them are fruits, palm trees, and pomegranates.

... In all Gardens will be noble, pleasant mates

...˹They will be˺ maidens [houris] with gorgeous eyes, reserved in pavilions.

.... No human or jinn has ever touched these ˹maidens˺ before.

... All ˹believers˺ will be reclining on green cushions and splendid carpets.

Then which of your Lord's favours will you both deny? (Q.55:46–76, Mustafa Khattab, the Clear Quran)[35]

Smith and Haddad summarize some of the Quranic pleasures:

Choirs of angels will sing in Arabic (the only language used in paradise), the streets will be as familiar as those of the dwellers' own countries, inhabitants will eat and drink 100 times more than earthly bodies could hold and will enjoy it 100 times more, their rooms will have thick carpets and brocade sofas, on Fridays they will go to a market to receive new clothing to enhance their beauty, they will not suffer bodily ailments or be subject to functions such as sleeping, spitting, or excreting; they will be forever young.[36]

As the gates of Jannah are opened for the arrival of the saved into Jannah they will be greeted (Q.39:73)[37] by angels announcing, "Peace be upon you, because ye have endured with patience; how excellent a reward is paradise!" (Q13:24).[38]

Inside there will be neither too much heat nor bitter cold; there will be fountains (Q.88:10), abundant shade from spreading tree branches green with foliage (Q.53:14–16, also Q.36:56–57).[37] They will be passed a cup (Q.88:10–16) full of wine "wherefrom they will get [no] aching of the head” (hangovers) [Q.56:19],[39] and "which leads to no idle talk or sinfulness" (Q.52:23),[Note 1] and every meat (Q.52:22) and trees from which an unceasing supply of fruits grow (Q.36:56–57),[18]: 58 "that looks similar ˹but tastes different˺"; (Q.2:25) adornment with golden and pearl bracelets (Q.35:33) and green garments of fine silk and brocade (Q.18:31); attended upon by [ghulman] (Q.52:24), servant-boys (eternal youths (56:17, 76:19)) like spotless pearls (Q.52:24).

While the Quran never mentions God being in the Garden, the faithful are promised the opportunity to gaze upon His face, something the inhabitants of the Fire will be deprived of.[10][Note 2]

Inhabitants will rejoice in the company of any parents, spouses, and children who were admitted to paradise (Q52:21) —conversing and recalling the past.[42]

One day in paradise is considered equal to a thousand years on earth. Palaces are made from bricks of gold, silver, pearls, among other things. Traditions also note the presence of horses and camels of "dazzling whiteness", along with other creatures. Large trees whose shades are ever deepening, mountains made of musk, between which rivers flow in valleys of pearl and ruby.[43][attribution needed]

- Non-physical pleasures

While the Quran is full of "graphic" descriptions of the "physical pleasures" for the inhabitants of the Garden, it also states that the "acceptance [riḍwān][44] from God" felt by the inhabitants "is greater" than the pleasure of the Gardens (Q.9:72),[36] the true beauty of paradise,[45][46] the greatest of all rewards, surpassing all other joys.[43] On the day on which God brings the elect near to his throne (‘arsh), "some faces shall be shining in contemplating their Lord".[43]

The visit is described as Muhammad leading the men and Fatimah leading the women to approach the Throne, "which is described as a huge esplanade of musk". As "the veil of light before the Throne lifts, God appears with the radiance of the full moon, and His voice can be heard saying, 'Peace be upon you.'"[47]

Hadith include stories of the saved being served an enormous feast where "God Himself is present to offer to His faithful ones delicacies kneaded into a kind of pancake".[47] In another series of narratives, God personally invites the inhabitants of Jannah "to visit with Him every Friday".[47]

- Houri

"Perhaps no aspect of Islamic eschatology has so captured the imagination" of both "Muslims and non-Muslims" as houri (ḥūr). Men will get untouched Houri in paradise (Q55:56), virgin companions of equal age (56:35–38) and have large, beautiful eyes (37:48). Houri have occasioned "spectacular elaborations" by later Islamic eschatological writers, but also "some derision by insensitive Western observers and critics of Islam".[36]

The Quran also states the saved "will have pure spouses," (without indicating gender) (Q2:25, Q4:57), accompanied by any children that did not go to Jahannam (Q52:21), and attended to by servant-boys with the spotless appearance similar to a protected pearls (Q52:24).

Despite the Quranic description above, Houris have been described as women who will accompany faithful Muslims in Paradise.[48][36] Muslim scholars differ as to whether they refer to the believing women of this world or a separate creation, with the majority opting for the latter.[49][Note 3]

Size, geography and structure

[edit]| Layers of Jannah according to different scholars (in descending order) | |

|---|---|

| al-Suyuti | Kitāb aḥwāl al-qiyāma |

| al-firdaws (Paradise) |

jannāt ʿadn ("garden of Eden") white pearl |

| jannat al-na'im ("garden of bliss") |

jannat al-firdaws red gold |

| jannat al-ma'wa ("garden of refuge") |

Jannat al na'īm ("garden of bliss") white silver |

| jannat 'adn ("garden of Eden") |

jannat al-khuld ("garden of eternity") yellow coral |

| dar al-khuld ("abode of eternity") |

jannat al-ma'wan ("garden of refuge") green chrysolite |

| dar al-salam ("abode of peace") |

dar al-salam ("abode of peace") red sapphire |

| dar al-jalal ("abode of glory") |

dar al-jinān ("abode of the garden") white pearl |

| Source: al-Suyuti;[5]: 131 | Source: Kitāb aḥwāl al-qiyāma[51] |

The Qur'an describes paradise as a "great kingdom" (Q.76:20) stretching out over and above the entire world,[5]: 41 and "lofty" (Q.69:22).[18]: 51

Paradise is "as vast as the heavens and the earth" (Q.3:133).[52] There are four rivers: one each of water, milk, honey, and wine (47:15).[37] (They were later identified as Kawthar, Kafur, Tasnim, and Salsabil.) [Note 4]

Despite the details given in the Quran about Jannah/Garden, "nowhere" is there found "an ordered picture of the structure" of the abode. "For the most part Islamic theology has not concerned itself with questions about the location and structure of the Garden and the Fire on the understanding that only God knows these particulars."[54]

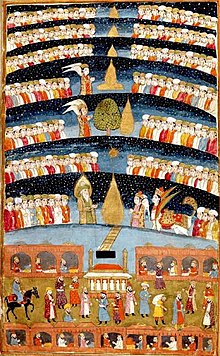

Layers/levels

[edit]Many sources agree that paradise has "various degrees and levels". One conservative Salafi source,[55] quotes as evidence a sahih hadith where Muhammad reassures the mother of a martyr, "O Umm Haarithah, there are gardens in Paradise ... and your son has attained the highest Firdaws”,[56] indicating a hierarchy of levels, but does not how many there are. On the basis of "several scriptural suggestions", scholars have created "a very detailed structure" of paradise,[14] but there is more than one, and not all of the traditions on location of paradise and hell "are easily pictured or indeed mutually reconcilable".[5]: 131

For example, Qu'ran 23:17 states "We created above you seven paths [Ṭarā'iq]" from which is drawn a heaven of seven tiers (which is also "a structure familiar to Middle Eastern cosmogony since the early Babylonian days").[14] Another school of thought insists Jannah actually has "eight layers or realms" as the Quran gives "eight different names ... for the abode of the blessed".[14] [Note 5]

Some descriptions of Jannah/the Garden indicate that the most spacious and highest part of the Garden, Firdaws, which is directly under the Throne and the place from which the four rivers of Paradise flow. Others say the uppermost portion is either the Garden of Eden or 'Iliyi and that is the second level from the top.[14]

Another possibility is that there are four separate realms of the blessed, of which either Firdaws or Eden is the uppermost. This is based on Surah 55, which talks about two Gardens: ("As for him who fears standing before his Lord there are two Gardens [Jannatan]") [S 55:46). All descriptions following this verse are of things in pairs, (i.e. in the Arabic dual form) – two fountains flowing, fruit of every kind in pairs, beside these two other gardens with two springs (Q.55:62,66).[58]

Still others have proposed that the seven levels suggested by the Qur'an are the seven heavens, above which is the Garden or final abode of felicity, while many see paradise as only one entity with many names.[37] (According to one source – a member of the fatwa team at Islamweb.net – only God knows the exact number of the levels of Paradise, but reliable hadith say the number of levels of Jannah may be the same as the number of verses in the Quran, i.e. over 6000 verses.)[59][Note 6]

One version of the layered Garden conceptualization describes the highest level of heaven (al-firdaws) as being said to be so close that its inhabitants could hear the sound of God's throne above.[5]: 132 This exclusive location is where the messengers, prophets, Imams, and martyrs (shahids) dwell.[5]: 133 Al-Suyuti[5]: 131 and Kitāb aḥwāl al-qiyāma[51] each gives names to the levels that do not always coincide (see table to right).

| Gates of Jannah according to different sources | |

|---|---|

| Soubhi El-Saleh | Huda Omam Khalid |

| salat (prayer) |

Bāb al-Ṣalāh: For those who were punctual in prayer |

| jihad (struggle for self betterment) |

Bāb al-Jihād: For those who took part in jihad |

| almsgiving | Bāb al-Ṣadaqah: For those who gave charity more often |

| sawm (fasting) |

Bāb al-Rayyān: For those who fasted (siyam) |

| repentance | Bāb al-Ḥajj: For those who participated in the annual pilgrimage |

| self-control | Bāb al-Kāẓimīn al-Ghayẓ wa-al-‘Āfīn ‘an al-Nās: For those who withheld their anger and forgave others |

| submission | Bāb al-Imān: For those who by virtue of their faith are saved from reckoning and chastisement |

| the door reserved for those whose entry to Paradise will be without preliminary judgment |

Bāb al-Dhikr: For those who showed zeal in remembering Allah |

| Source: Soubhi El-Saleh, based on numerous traditions[60] |

Sources: Doors of Jannah[61] Islam KaZir[62] |

Gates/doors

[edit]Two verses of the Quran (Qu'ran 7:40, 39:73) mention "gates" or "doors" (using the plural form) as the entrance of paradise, but say nothing about their number, names or any other characteristics.

- "To those who reject Our signs and treat them with arrogance, no opening will there be of the gates of heaven ..." (Qu'ran 7:40)

- "And those who kept their duty to their Lord (Al-Muttaqoon – the pious) will be led to Paradise in groups till when they reach it, and its gates will be opened" (Qu'ran 39:73)

As in the case of the levels of Jannah, later sources elaborate, giving names and functions but don't agree on all details (see table to right).[37][Note 7]

In traditions, each level of the eight principal gates of Paradise is described as generally being divided into a hundred degrees guarded by angels (in some traditions Ridwan). The highest level is known as firdaws (sometimes called Eden) or Illiyin. Entrants will be greeted by angels with salutations of peace or As-Salamu Alaykum.[43]

Jannah is accessible vertically through its gates (Qu'ran 7:40), by ladders (ma'arij) (Qu'ran 70:3), or sky-ropes (asbab). However, only select beings such as angels and prophets can enter.[64] Iblis (Satan) and devils are kept at bay by angels who throw stars at them, whenever they try to climb back to heaven (Q.37:6–10).[5]: 41 Notably and contrary to many Christian ideas on heaven, God (Allah) does not reside in paradise.[5]: 11 [Note 8]

Rivers

[edit]A few hadith name four rivers in paradise, or coming from paradise, as: Saihan (Syr Darya), Jaihan (Amu Darya), Furat (Euphrates) and Nil (Nile).[66][67][Note 9][70] Salsabil is the name of a spring that is the source of the rivers of Rahma (mercy) and Al-Kawthar (abundance).[71] Sidrat al-Muntaha is a Lote tree that marks the end of the seventh heaven, the boundary where no angel or human can pass.[72][further explanation needed] Muhammad is supposed to have taken a pomegranate from jannah, and shared it with Ali, as recorded by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. However, some scholars, like Ghazali, reject that Muhammad took the fruit, argued he had only a vision instead.[5]

Literal or allegorical

[edit]According to scholars Jane I. Smith, Yvonne Y. Haddad, while there are Muslims of a "philosophical or mystical" bent who interpret descriptions of heaven and hell "metaphorically", "the vast majority of believers", understand verses of the Quran on Jannah (and hellfire) "to be real and specific, anticipating them" with joy or terror,[73] although this view "has generally not insisted that the realities of the next world will be identical with those of this world".[73] Besides the material notion of the paradise, descriptions of it are also interpreted as allegories, whose meaning is the state of joy believers will experience in the afterlife. For some theologians, seeing God is not a question of sight, but of awareness of God's presence.[74] Although early Sufis, such as Hallaj, took the descriptions of Paradise literal, later Sufi traditions usually stressed out the allegorical meaning.[75]

Eternal, not temporal

[edit]While some Quranic verses suggest hellfire is eternal and some that its punishment will not necessarily be forever for Muslims who committed grave sins, verses on Jannah are less ambiguous. Eternality assured in verses about paradise such as Qu'ran 3:198, 4:57, and 57:12, which say that the righteous will be khālidūn fīhā (eternally in it), and Qu'ran 35:35, which describes the reward of dār al-maqāma [the abode of everlastingness].[76] Consequently, neither "theologians nor the traditionalists" have had any doubts about the eternal nature of paradise or the residence of the righteous in it.[77][78]

Other characteristics

[edit]To classical scholars on the afterlife al-Suyūṭī and al-Majlisī, one of the characteristics of Jannah (like hellfire) is that events are not "frozen in one eternal moment", but form cycles of "endless repetition" and "unceasing self renewing clockwork".[5]: 129-130 For example, when a fruit is plucked from a tree, a new fruit immediately appears to takes its place; when a hungry inhabitant sees a bird whose meat they would like to eat it falls already roasted into their hands, and after they are done eating, the bird "regains its form shape and flies away";[5]: 130 houri regain their virginity after being deflowered by one of the saved, but they also grow like fruit on trees or plants on the land and "whenever one of them is taken" by one of the saved in paradise one for his pleasure, "a new one springs forth in her place".[5]: 130 (So too in hellfire are the skin of the damned replaced each time that they are burned off by the fire to be burned again, and drowning sinners driven back into the sea by giant snakes and scorpions whernever they reach the safety of shore.)[5]: 130

Garden of Eden and Paradise

[edit]

Muslim scholars differ on whether the Garden of Eden (jannāt ʿadni), in which Adam and Eve (Adam and Hawwa) dwelled before being expelled by God, is the same as the afterlife abode of the righteous believers: paradise. Most scholars in the early centuries of Islamic theology and the centuries onwards thought it was and that indicated that paradise was located on earth.[5]: 166 It was argued that when God commanded Adam to "go down" (ihbit) from the garden, that did not indicate a vertical movement (such as "falling" from a heaven above to earth), but instead was used in the same sense as Moses telling Israelites to "go down to Egypt".[5]: 166

However, as paradise came over the centuries to be thought of more and more as "a transcendent, otherworldy realm", the idea of it being located somewhere on earth fell out of favor. The Garden of Eden, on the other hand lacked many transcendent, otherworldy characteristics. Al-Balluti (887–966) reasoned that the Garden of Eden lacked the perfection and eternal character of a final paradise:[5]: 167 Adam and Eve lost the primordial paradise, while the paradisiacal afterlife lasts forever; if Adam and Eve were in the otherworldly paradise, the devil (Shaiṭān) could not have entered and deceive them since there is no evil or idle talk in paradise; Adam slept in his garden, but there is no sleep in paradise.[5]: 167

Many adherences of the Muʿtazila, also refused to identify Adam's abode with paradise, because they argued that paradise and hell would not be created until after Day of Judgement, an idea proposed by Dirar b. Amr.[5]: 167 Most Muslim scholars, however, assert that paradise and hell have been created already and coexists with the contemporary world, taking evidence from the Quran, Muhammad's heavenly journey, and the life in the graves.[5]: 168 [79]

Islamic exegesis regards Adam and Eve's expulsion from paradise not as punishment for disobedience or a result from abused free will on their part,[5]: 171 but as part of God's wisdom (ḥikma) and plan for humanity to experience the full range of his attributes, his love, forgiveness, and his creation's power.[5] By experiencing hardship, they better appreciate paradise and its delights.[5] Khwaja Abdullah Ansari (1006–1088) describes Adam and Eve's expulsion as ultimately caused by God,[80]: 252 since man has no choice but to comply to God's will. However, that does not mean that complying is not a "sin" and that humans should not blame themselves for it.[80]: 252 That is exemplified by Adam and Eve in the Quran (Qu'ran 7:23 "Our Lord! We have wronged ourselves. If You do not forgive us and have mercy on us, we will certainly be losers".)

Comparison with other religions

[edit]Comparison with Judaism

[edit]Jannah shares the name "Garden of the Righteous" with the Jewish concept of paradise. In addition, paradise in Judaism is described as a garden, much like the Garden of Eden, in which people live and walk and dance, wear garments of light and eat the fruit of the tree of life.[citation needed] Like the feast of Jannah, Jewish eschatology describes the Messiah holding a Seudat nissuin, called the Seudat Chiyat HaMatim, with the righteous of every nation at the end time.[81]

Comparison with Christianity

[edit]Jesus in the Gospels uses various images for heaven that are similarly found in Jannah: feast, mansion, throne, and paradise.[82] In Jannah, humans stay as humans, but the Book of Revelation describes that in heaven Christ "will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body" (Philippians 3:21). God (Allah) does not reside in paradise or heaven. However, in Christianity, the new heavens and the new earth will be where God dwells with humans.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The Quran says in reference to heavenly wine drinking: "Round them will be passed a cup of pure wine ... Neither will they have Ghoul (any kind of hurt, abdominal pain, headache, a sin) from that nor will they suffer intoxication therefrom” ([al-Saaffaat 37:45–47).[39] Smith & Haddad say "While the Qur'an insists that no aftereffects will occur from imbibing the wines of the Garden's rivers, the possibilities of heavenly intoxication have afforded the type of fanciful description found in Abū Layth al-Samarqandī, reportedly from Muhammad:

On Saturday God Most High will provide drink [from the water of the Garden]. On Sunday they will drink its honey, on Monday they will drink its milk, on Tuesday they will drink its wine. When they have drunk, they will become intoxicated; when they become intoxicated, they will fly for a thousand years till they reach a great mountain of fine musk from beneath which emanates Salsabil. They will drink [of it] and that will be Wednesday. Then they will fly for a thousand years till they reach a place overtopping a mountain ...[40]

- ^ Some early Muslims, such as Muʿtazila and Jahmiyah, opposed to anthropomorphism, denied this possibility. "The majority opinion, however, rejected ... opposition to the possibility of the ru'ya Allah, following the conclusions of the school of al Ash'ari" and argued that "the precise means" of that vision of God "as well as its content must for now be unexplainable ..."[41]

- ^ Lange argues that "purified spouses" cannot refer to houris as they are heavenly creatures not in need of ritual cleansing. [50]

- ^ The names given the rivers come from the Quran, where they are identified as sources of water with religious significance, but not as rivers of honey, wine, etc. in paradise.

- Q.76:5 on the water of Kafur, of which the righteous shall drink;

- Q.83:27–28 on the waters of Tasnim drunk by those brought near to God;

- Q.76:18 on the water of a spring named Salsabil; and

- Q.108:1, which speaks only of abundance [kawthar]. The last is sometimes applied to a river running through the Garden and sometimes to the hawq of Muhammad.[53]

- ^ "Five descriptions are used" in the Quran "in conjunction with Janna, singular or plural: the garden of eternity [al-khuld] (Qu'ran 25:15), the gardens of Firdaws (Q 18: 107), the gardens of refuge [al-ma'wan] (Qu'ran 32:19), the gardens of bliss [al-na'im] (Qu'ran 5:65), and the gardens of Eden (Qu'ran 9:72). Two are in conjunction with dlir, abode: abode of peace [sallim] (Qu'ran 6:127) and abode of repose [qarlir] (Qu'ran 40:39); the last is 'iliytn (Qu'ran 83:18).[57]

- ^ '... based on the hadeeth of ‘Abd-Allaah ibn ‘Amr, who said that the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said: "It will be said to the companion of the Qur’aan: ‘Recite and rise in status as you used to recite in the world, and your position will be at the last verse you recite.'" Narrated by Abu Dawood, 1646; al-Tirmidhi, 2914; classed as saheeh by al-Albaani in Saheeh Abi Dawood.'[55]

- ^ See Soubhi El-Saleh (La Vie Future, chapter 1, pt. 3), who cites numerous traditions describing the gates and gives their categorizes (see table to right). Al-Samarqandi (Macdonald, "Paradise." Islamic Studies, 5 (1966), p. 343) gives a similar classification, although the order and some of the particulars differ; cf. Kitāb aḥwāl al-qiyāma, pp. 105–106, which presents the same description.[63]

- ^ "...Muslim literature on the otherworld often stresses that God does not reside in Paradise, but above it."[65]

- ^ According to the website Questions on Islam, "The number of the rivers coming from Paradise is mentioned as three in some narrations and four and five in others."

- Three rivers:"For instance, while explaining the sentence “For among rocks there are some from which rivers gush forth” in verse 74 of the chapter of al-Baqara in his book called Sözler (Words), Badiuzzaman Said Nursi attracts attention to the rivers like the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates and quotes the hadith 'The source of each of those three rivers is in Paradise.'"

- Four rivers: "In most of the hadith books including Muslim, four rivers that come from Paradise are mentioned."[68]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Searchable Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic" (PDF). giftsofknowledge. p. 138. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Joseph Hell Die Religion des Islam Motilal Banarsidass Publishers 1915

- ^ "Paradise In Quran". The Last Dialogue. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Thomassen, "Islamic Hell", Numen, 56, 2009: p.401

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Lange, Christian (2016). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-50637-3.

- ^ a b "Eschatology (doctrine of last things)". Britannica. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Emerick, Yahiya (2011). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Islam (3rd ed.). Penguin. ISBN 9781101558812.

- ^ Tom Fulks, Heresy? The Five Lost Commandments, Strategic Book Publishing 2010 ISBN 978-1-609-11406-0 p. 74

- ^ Thomassen, "Islamic Hell", Numen, 56, 2009: p.405

- ^ a b Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.86

- ^ Lange, Christian (2016). "Introducing Hell in Islamic Studies". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. BRILL. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-04-30121-4. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.7.

- ^ "Surah Nabaa, Chapter 78". al-Islam. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "english tafsir. Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi – Tafhim al-Qur'an – The Meaning of the Qur'an. 78. Surah An Naba (The News)". englishtafsir.com. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.87

- ^ Asad, Muhammad (1984). The Message of the Qu'rán (PDF). Gibraltar, Spain: Dar al-Andalus Limited. pp. 712–713. ISBN 1904510000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ Asad, Muhammad (1984). The Message of the Qu'rán (PDF). Gibraltar, Spain: Dar al-Andalus Limited. p. 531. ISBN 1904510000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ Begley, Wayne E. The Garden of the Taj Mahal: A Case Study of Mughal Architectural Planning and Symbolism, in: Wescoat, James L.; Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (1996). Mughal Gardens: Sources, Places, Representations, and Prospects Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C., ISBN 0884022358. pp. 229–231.

- ^ a b c d Günther, Sebastian; Lawson, Todd (2017). Roads to Paradise: Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam (2 vols.): Volume 1: Foundations and Formation of a Tradition. Reflections on the Hereafter in the Quran and Islamic Religious Thought / Volume 2: Continuity and Change. The Plurality of Eschatological Representations in the Islamicate World. Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_0300. ISBN 978-9-004-33315-4.

- ^ Moiz Amjad. "Will Christians enter Paradise or go to Hell? Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine". Renaissance – Monthly Islamic journal 11(6), June, 2001.

- ^ Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam [Demonic Belief in Islam] (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- ^

el-Zein, Amira (2009). Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-5070-6. - ^ David Marshall Communicating the Word: Revelation, Translation, and Interpretation in Christianity and Islam Georgetown University Press 2011 ISBN 978-1-589-01803-7 p. 8

- ^ Lloyd Ridgeon Islamic Interpretations of Christianity Routledge 2013 ISBN 978-1-136-84020-3

- ^ Reinhart, Kevin; Gleave, Robert (2014). "Sins, expiation, and non-rationality in fiqh". In Lange, Christian (ed.). Islamic Law in Theory: Studies on Jurisprudence in Honor of Bernard Weiss. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9780567081612.

- ^ McKim, Robert (2016). "Pluralism in Jewish, Christian and Muslim thought". Religious Perspectives on Religious Diversity. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004330436.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Rico; Frigerio, Alessandro (2018). "Pluralism in Jewish, Christian and Muslim thought". Theorizing Central Asian Politics: The State, Ideology and Power. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9783319973555.

- ^ Awaa'il al-Maqaalaat by Shaikh al-Mufeed, p.14

- ^ Al-Musawi, Sayyed Mohammad (2020). "Is it a Shi'i belief that every Muslim, including people like Umar ibn Sa'd and Ibn Ziyad, will eventually enter paradise after being punished for their sins? Is there any Islamic sect that has such a belief?". al-Islam.org. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Tehrani, Ayatullah Mahdi Hadavi (5 September 2012). "Question 13: Non-muslims and Hell". Faith and Reason. Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b Der Koran, ed. and transl. by Adel Theodor Khoury, Gütersloh 2004, p. 67 (footnote).

- ^ "An-Nisa 123–124". Quran.com. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.vii

- ^ a b Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.viii

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel. Islam and The Wonders of Creation: The Animal Kingdom. Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2003. Page 46

- ^ Taylor, John B. (October 1968). "Some Aspects of Islamic Eschatology". Religious Studies. 4 (1): 60–61. doi:10.1017/S0034412500003395. JSTOR 20000089. S2CID 155073079.

- ^ a b c d Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.89

- ^ a b c d e Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.88

- ^ Sale, George (1891). The Koran: Commonly Called the Alkoran of Mohammed... New York: John B. Alden.

- ^ a b "The difference between the wine of this world and the Hereafter". Islam Question and Answer. 2009-10-07. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.89–90

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.95–96

- ^ Quran 55:56-58, 56:15–25

- ^ a b c d "Jannah", Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ^ Some texts indicate that riḍwān is the name' of the guardian of paradise who receives the faithful into the Garden.

- ^ Mouhanad Khorchide, Sarah Hartmann Islam is Mercy: Essential Features of a Modern Religion Verlag Herder GmbH ISBN 978-3-451-80286-7 chapter 2.4

- ^ Farnáz Maʻsúmián Life After Death: A Study of the Afterlife in World Religions Kalimat Press 1995 page 81

- ^ a b c Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.96

- ^ "Houri" Archived 2021-09-21 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr; Caner K. Dagli; Maria Massi Dakake; Joseph E.B. Lumbard; Mohammed Rustom, eds. (2015). The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-112586-7.

- ^ Lange, Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions, 2016: p.52

- ^ a b Kitāb aḥwāl al-qiyāma, pp.105–06. quoted in Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.88

- ^ abdullahamir (6 July 2020). "A Paradise as vast as the Heavens and the Earth". Islamic Web Library. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.217 note 76

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.91

- ^ a b "The degrees and levels of Paradise and Hell, and the deeds that take one to them. 27075". Islam Question and Answer. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Sahih al-Bukhari » 2809 » Book 56, Fighting for the Cause of Allah (Jihaad) (14) Chapter: Whoever is killed by an arrow. Narrated Anas bin Malik". sunnah.com. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.217 note 72

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.87–88

- ^ "Levels of Paradise Exceed One Hundred". Islamweb.net. 2020-02-01. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Soubhi El-Saleh (La Vie Future selon le Coran. Paris: Librarie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1971, chapter 1, pt. 3); cited in Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.217–218 note 77

- ^ Huda (7 May 2018). "Doors of Jannah". Learn Religions. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Khan, Saad (5 July 2021). "8 Gates Of Jannah in Islam & Who Will Enter From Them". Islam KaZir. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.217–218 note 77

- ^ Sachiko Murata The Tao of Islam: A Sourcebook on Gender Relationships in Islamic Thought SUNY Press 1992 ISBN 978-0-791-40913-8 page 127

- ^ Lange, Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions, 2016: p.11

- ^ Muslim. "Sahih Muslim 2839. (10) Chapter: Rivers Of Paradise In This World. Abu Huraira reported Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) as saying: Saihan, Jaihan, Euphrates and Nile are all among the rivers of Paradise". Sunnah.com. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Al-Nawawi. "Riyad as-Salihin 1853. (370) Chapter: Ahadith about Dajjal and Portents of the Hour. Abu Hurairah ... said: The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said, "Saihan (Oxus), Jaihan (Jaxartes), Al-Furat (Euphrates) and An-Nil (Nile) are all from the rivers of Jannah."". Sunnah.com. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Are there rivers that originate/come from Paradise?". Questions on Islam. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Badiuzzaman Said Nursi. Sözler (Words), Yirminci Söz (Twentieth Word). p. 260.; quoted in "Are there rivers that originate/come from Paradise?". Questions on Islam. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ Hughes, Patrick (1995). "EDEN". A Dictionary of Islam. New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Services. p. 106. ISBN 9788120606722.

- ^ Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi (2004). Divine sayings (Mishkat al-Anwar). Oxford, UK: Anqa Publishing. pp. 105, note 7. ISBN 0-9534513-5-6.

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān Volume 1 Georgetown University, Washington DC p.32

- ^ a b Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.84

- ^ Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith The New Encyclopedia of Islam Rowman Altamira 2003 ISBN 978-0-759-10190-6 page 237

- ^ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān Volume 2 Georgetown University, Washington DC p. 268

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: pp.92–93

- ^ Some exceptions to this include the followers of Jahm ibn Ṣafwān, who "denied the eternality of both the Garden and the Fire".

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.93

- ^ Smith & Haddad, Islamic Understanding, 1981: p.92

- ^ a b Awn, Peter J. (1983). "The Ethical Concerns of Classical Sufism". The Journal of Religious Ethics. 11 (2): 240–263. JSTOR 40017708.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Eschatology

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1027

Bibliography

[edit]- Lange, Christian (2016). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-50637-3.

- Rustomji, Nerina (2009). The Garden and the Fire: Heaven and Hell in Islamic Culture. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231140850. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- Smith, Jane I.; Haddad, Yvonne Y. (1981). The Islamic Understanding of Death and Resurrection. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Thomassen, Einar (2009). "Islamic Hell". Numen. 56 (2–3): 401–416. doi:10.1163/156852709X405062. JSTOR 27793798.