Auxerre Cathedral

| Auxerre Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathédrale Saint-Étienne d'Auxerre | |

Auxerre Cathedral | |

| |

| 47°47′52″N 3°34′22″E / 47.7979°N 3.5729°E | |

| Location | Auxerre, |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architectural type | Gothic, Renaissance |

| Groundbreaking | 13th century |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Sens and Auxerre |

Auxerre Cathedral (French: Cathédrale Saint-Étienne d'Auxerre) is a Roman Catholic church, dedicated to Saint Stephen, located in Auxerre, Burgundy, France. It was constructed between the 13th and 16th centuries, on the site of a Romanesque cathedral from the 11th century, whose crypt is found underneath the cathedral.[1] It is known for 11th century Carolingian frescoes found in the crypt, and for its large stained glass windows.[2] Since 1823 it has been the seat of a diocese united with that of Sens Cathedral.[3]

History

[edit]The first Christian diocese in Auxerre was established at the end of the 3rd century by its first bishop, Germanus of Auxerre. The original Romanesque cathedral was completed in 1057. The crypt of that structure was immense, with three naves and six traverses. It also featured a new architectural element, a disambulatory, a passage which permitted pilgrims to circulate and visit the tombs in the crypt without disturbing the religious services attended by the clergy.[3]

The construction of the Gothic cathedral was begun in about 1215, led by Bishop Robert de Seignelay.[4] He set an example by contributing heavily and consistently from his own resources, and continued to bequeath funds after his transfer to the see of Paris in 1220.[5] The new Cathedral, along with that of Dijon Cathedral, became models of the Burgundian Gothic style.[3]

Most of this portion of the cathedral was finished by 1233. After this, the work slowed down considerably. The chevet, or east end, was completed by De Seignelay's successor, Henri de Villeneuve (1220–34); he left 1000 livres for the project, but construction slowed after his death, hampered by a shortage of funds. The construction of the west front did not begin until the end of the 13th century. The south transept was not completed until 1358. Most of the nave walls were finished by 1395, but the nave vaults were not completed until the beginning of the 15th century.[6]

Construction resumed in the 16th century with the north tower, built in the richly ornamented Flamboyant Gothic style, completed in 1543. However, the Wars of Religion led to the devastation of the cathedral in 1567. The planned south tower was never constructed.[7] [8]

The transepts were also completed in the 16th century; the rose window called the Virgin of the Litanies in the north arm of the transept, made by Germain Michel, was finished in 1528, while the rose window of the south transept, by Guillaume Cornouvaille, was installed in 1550.

In 1567, during the Wars of Religion, Protestant bands pillaged the city, and caused considerable damage to the cathedral. The damage was largely repaired by 1576 under Bishop Jacques Amyot.

In 1764 the very ornate Gothic rood screen, or choir grill, put in place under King Francois I of France, was destroyed, in keeping with a new Vatican anti-Reformation doctrine to make the interior more appealing to ordinary churchgoers. It was replaced by a lacelike iron grill made by the Paris iron craftsman Dhumier, with gates by sculptor Sébastien Slodtz to a design by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.

Exterior

[edit]-

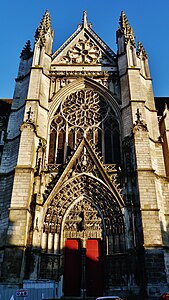

The west front and north tower

-

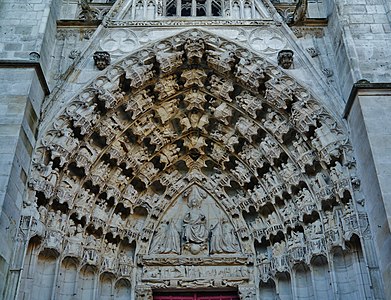

Central portal of the west front

-

The flamboyant south transept

-

The flamboyant north transept

-

The chevet, or east end

The narrative sculptural program of the portals on the west end are noted for their extent and variety.[9]

The stimulus was provided about 1270 by Jean de Châlons-Rochefort, who had recently become Count of Auxerre, having supported the Duke of Burgundy against his own brother, by marrying Alix, the heiress of Auxerre. He was the largest fief-holder in the duchy and commemorated the new status of his fief of Auxerre by enriching the front of its chief ornament, the cathedral, whose Carolingian nave had been erected by his ancestor Hugh de Châlons, 10th-century bishop of Auxerre. Its program of sculpture was carried through long after his death and completed in the early 15th century.[10]

North Tower

[edit]-

North tower and base of unfinished south tower

The construction of the north tower began in about 1250, and reached the completion of the portal at its base, but then practically ceased for nearly two centuries. The work did not resume the beginning of the 16th century. The upper portions were built largely in the ornate flamboyant Gothic style, and were completed in about 1543.[11]

The tower contains the belfry of the cathedral, within the fifth, or top level. It is approximately the same height as the towers of Notre-Dame de Paris. The three levels above the portal are decorated with niches covered by gables. The roof has a small terrace surrounded by a balustrade. The tower is given a more graceful silhouette by the prolongation of the buttresses at the angles. The buttresses are also ornamented and prolonged by slender spires. On the northeast side of the tower is attached a slender octagonal tower with narrow windows, which serves as a stairway from the base of the tower to the summit. At the top it has its own Renaissance-style belfry and a lantern, adorned with a cross marking the highest point of the cathedral.

A south tower similar to the north tower was planned, and the base and buttresses for the tower were constructed, with walls two meters thick, next to the narthex, and a second level above, but it went no higher. Later in the 16th century The cathedral chapter decided to rebuild the oratory to house a statue of the Virgin Mary rather than building the tower higher. The unfinished tower base reaches as far into the interior as the first traverse of the nave. A spiral staircase is encased in the massive stone construction. To the right of the north tower base are the vestiges of the chapel of Notre-Dame-des-Vertus, built in the 16th century but demolished in 1780.

Nave and Choir

[edit]-

The nave

-

The choir, at the east end

-

The disambulatory at the east end

The choir, built atop the Romanesque crypt, was begun first in about 1215, in a plan similar to another Burgundian church, Dijon Cathedral. The elevation has three levels; large arcades with pillars at the bottom; a narrow triforium, or passageway, above, with windowless arches and decoration by slender colonettes; and on the top level, double lancet windows below circular rose windows, with a narrow passageway along the wall at their base.

The nave was originally planned to have a ceiling of six-part rib vaults, supported by alternating massive pillars and columns, but this plan was modified to have the more modern and stronger four-part rectangular rib vaults.

Another notable architectural feature is the junction between the axial chapel at the east end with the disambulatory, the interior passage the surrounds the east end interior, allowing visitors to circulate while services were going on in the choir. In this disambulatory, the six-part vaults are supported by slender columns twenty-five centimetres in diameter, which give unity of style and animation to the end of the church.[6]

Crypt

[edit]-

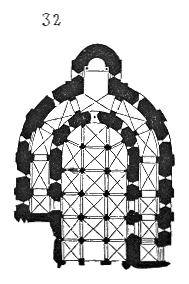

Plan of the crypt, and its ambulatory

-

Ceiling of the crypt

-

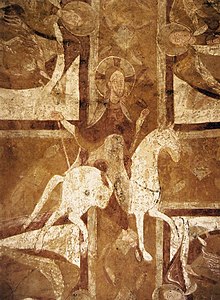

Image of Christ in the Crypt

-

Christ on a White Horse (12th c.)

-

ambulatory of the crypt

The crypt beneath the choir was constructed between by Bishop Hugues de Chalon, when he rebuilt the earlier Romanesque structure. It features an early disambulatory, allowing circulation by pilgrims around the tombs without disturbing services in the center. It contains the oldest art in the cathedral, including frescoes of Christ at the time of the Apocalypse commissioned by Bishop Humbaud, and a later fresco of Christ in Majesty from the end of the 13th century.[12]

Stained glass

[edit]-

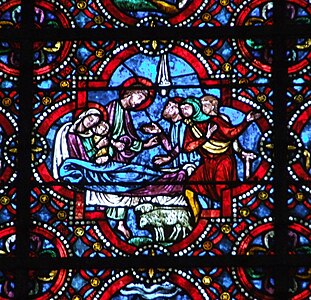

Windows in Chapel of Notre-Dame (first half of 13th century)

-

Detail of 13th c. window in Chapel of Notre-Dame

-

South disambulatory window (c. 1240)

-

Joan of Arc Window

The cathedral has an important collection of 13th century stained glass. This includes some sixty windows made between 1235 and 1250, mostly found in the Chapel of Notre-Dame and in the ambulatory. They are known for the deep, rich blues and reds of the thick pieces of glass, assembled like parts of a mosaic.[13] The windows in the bays of the nave date from the 15th century, and are in the Renaissance style. The rose windows of the transept date from the 16th century. [14]

Rose windows

[edit]-

The south transept

-

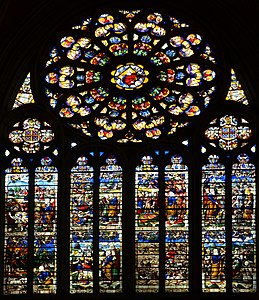

North transept rose window (completed 1528) (click twice to see detail)

-

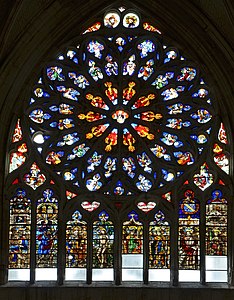

The south transept rose window (1550)

-

Rose window on the west front (16th c.)

The north portion of the transept was completed, along with its flamboyant rose window, in 1528. The south transept and rose window were completed in 1550. The south rose window has an oculus in the centre representing God the father, over eight lancet windows depicting the life of Moses. The windows were made by Guillaume Cornovaille.[15]

Art and decoration

[edit]-

Tympanum of the Last Judgement, central portal (click 3 times to enlarge)

-

Traces of colored wall paintings; John the Baptist (left) and a Bishop

-

The choir screen (1764)

-

Misericorde or resting spot on a seat back in the choir

The cathedral has a very rich collection of sculpture, particularly in the arches over the main portal on the west front. This collection of densely-packed sculptures includes both religious figures and allegorical figures of the wives of Hercules and the sleeping goddess Eros. [6]

An important decorative feature of the interior is the elaborate wrought iron choir screen, which replaced the old rood screen in 1764. It was made by the Paris iron craftsman Dhumier, with gates by the royal sculptor Sébastien Slodtz to a design by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.[16]

The cathedral choir has a remarkable collection of misericordes, the sculpted wood medallions on the seat backs in the choir, which provided a resting place when the clergy had to stand for long periods of time.

The organ

[edit]-

Grand organ

The grand organ of the cathedral was built in the 19th century, and installed in a Neo-Gothic style case. It was entirely rebuilt between 1979 and 1986 by Dominique Oberthür de Saintes, who transformed it into a modern instrument, with forty-six stops, four manual keyboards, and mechanical transmission by carbon fibres. Following damage from a storm in 2005, it received further restoration between 2011 and 2012 and was given additional stops, including stops En chamade, which sound directly outward, like trumpets, to the nave. [17]

The bells

[edit]The bell tower contains the four major bells of the cathedral:

- Thérèse: the bourdon, or largest and deepest bell: 4,750 kilograms (1836)

- Marguerite: 2,500 kilograms (1841) by Jean-Claude II Burdin at Lyon

- Marie-Félicité 1.800 kilograms (1841), by Jean-Claude II Burdin at Lyon

- Marie-Anne: 550 kilograms (1841) by Jean-Claude II Burdin at Lyon

Rung altogether, they create a harmony in G major.

The diocese

[edit]Auxerre was formerly an important diocese in Gaul, with a bishop as early as the 3rd century; the diocese was suppressed in 1821.[18] A council held at Auxerre in 585 (or 578) under bishop Annacharius formulated forty-five canons, closely related in context to canons of the contemporary first and second Councils of Lyon and the Council of Mâcon. "They are important as illustrating life and manners among the newly-converted Teutonic tribes and the Gallo-Romans of the time", the Catholic Encyclopedia asserts. Many of the decrees were directed against remnants of paganism and non-Christian customs; others bore witness to the persistence in the early Middle Ages in France of certain ancient Christian customs. The canons of the council of 695 or 697 were concerned chiefly with the Divine Office and ecclesiastical ceremonies.[19]

See also:

- Saint Germanus of Auxerre, bishop of Auxerre (died 448)

- Desiderius of Auxerre, bishop, died 621)

- Remigius of Auxerre, theologian and teacher (died 908)

- William of Auxerre, theologian (1140/50–1231)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Le Guide du Patrimoine en France" (2002), p. 148

- ^ The glass was reassembled after a Protestant iconoclastic attack on it in 1567; Virginia Chieffo Raguin, "The Genesis Workshop of the Cathedral of Auxerre and Its Parisian Inspiration" Gesta 13.1 (1974:27–38) p. 28.

- ^ a b c Lours 2018, p. 67.

- ^ His vita in Gesta Pontificum Autissiodorensium is the primary source for the building campaign.

- ^ C. Porée, La cathédrale d'Auxerre (Paris) 1926.

- ^ a b c Lours 2018, p. 68.

- ^ The first Burgundian example of the High Gothic; Harry B. Titus, Jr., "The Auxerre Cathedral Chevet and Burgundian Gothic Architecture" The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 47.1 (March 1988:45–56) p.

- ^ Lours 2018, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Don Denny, "Some Narrative Subjects in the Portal Sculpture of Auxerre Cathedral" Speculum 51.1 (January 1976:23–34).

- ^ Denny 1976:

- ^ Site Structurae.de : histoire de la cathédrale d'Auxerre

- ^ Site Structurae.de : histoire de la cathédrale d'Auxerre

- ^ Site Structurae.de : histoire de la cathédrale d'Auxerre

- ^ Lours 2018, p. 69.

- ^ Site Structurae.de : histoire de la cathédrale d'Auxerre

- ^ Site Structurae.de : histoire de la cathédrale d'Auxerre

- ^ "Saint-Etienne retrouve sa voix", Auxerre television, July 4, 2012

- ^ Catholic Hierarchy: diocese of Auxerre (Suppressed).

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. The source doesn't give a clear date for the councils.

Bibliography

[edit]- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (in French). Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. 2002. ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0.

- Lours, Mathieu (2018). Dictionnaire des Cathédrales (in French). Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot. ISBN 978-2755-807653.

External links

[edit]- Cathédrale Saint-Étienne d'Auxerre at Structurae

- "Welcome to Auxerre Cathedral"

- Auxerre Cathedral bibliography

- Photos

- Catholic Encyclopedia 1908: "Councils of Auxerre" "(Sens):Diocese of Auxerre"

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Auxerre Cathedral | Art Atlas