Law report

Law reports or reporters are series of books that contain judicial opinions from a selection of case law decided by courts. When a particular judicial opinion is referenced, the law report series in which the opinion is printed will determine the case citation format.

Historically, the term reporter was used to refer to the individual persons who actually compile, edit, and publish such opinions.[1] For example, the Reporter of Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States is the person authorized to publish the Court's cases in the bound volumes of the United States Reports. Today, in American English, reporter also denotes the books themselves.[2] In Commonwealth English, these are described by the plural term law reports, the title that usually appears on the covers of the periodical parts and the individual volumes.

In common law countries, court opinions are legally binding under the rule of stare decisis (precedent). That rule requires a court to apply a legal principle that was set forth earlier by a court of a superior (sometimes, the same) jurisdiction dealing with a similar set of facts. Thus, the regular publication of such opinions is important so that everyone—lawyers, judges, and laymen—can all find out what the law is, as declared by judges.

Official and unofficial case law reporting

[edit]Official law reports or reporters are those authorized for publication by statute or other governmental ruling.[3] Governments designate law reports as official to provide an authoritative, consistent, and authentic statement of a jurisdiction's primary law. Official case law publishing may be carried out by a government agency, or by a commercial entity. Unofficial law reports, on the other hand, are not officially sanctioned and are published as a commercial enterprise. In Australia and New Zealand (see below), official reports are called authorised reports—unofficial reports are referred to as unauthorised reports.

For the publishers of unofficial reports to maintain a competitive advantage over the official ones, unofficial reports usually provide helpful research aids (e.g., summaries, indexes), like the editorial enhancements used in the West American Digest System. Some commercial publishers also provide court opinions in searchable online databases that are part of larger fee-based, online legal research systems, such as Westlaw, Lexis-Nexis or Justis.

Unofficially published court opinions are also often published before the official opinions, so lawyers and law journals must cite the unofficial report until the case comes out in the official report. But once a court opinion is officially published, case citation rules usually require a person to cite to the official reports.

Contents of a good law report

[edit]

A good printed law report in traditional form usually contains the following items:

- The citation reference.

- The name of the case (usually the parties' names).

- Catchwords (for information retrieval purposes).

- The headnote (a brief summary of the case, the holding, and any significant case law considered).

- A recital of the facts of the case (unless appearing in the judgment).

- A note of the arguments of counsel before the judge. (This is often omitted in modern reports.)

- The judgment (a verbatim transcript of the words used by the judge to explain his or her reasoning).

It is only the last item that is authoritative. The others, although useful for its understanding, are only the law reporter's contribution. Thus, law students are warned that the headnote is not part of the decision rendered, since headnotes occasionally contain misinterpretations of the law, and are not part of the official judgment. (In the United States, however, the headnote, also called the syllabus, is sometimes written by the court itself, which fact is stated.)

Open publication on the Internet

[edit]The development of the Internet created the opportunity for courts to publish their decisions on Web sites. This is a relatively low cost publication method compared to paper and makes court decisions more easily available to the public (particularly important in common law countries where court decisions are major sources of law). Because a court can post a decision on a Web site as soon as it is rendered, the need for a quickly printed case in an unofficial, commercial report becomes less crucial. However, the very ease of internet publication has raised new concerns about the ease with which internet-published decisions can be modified after publication, creating uncertainty about the validity of internet opinions.[4]

Decisions of courts from all over the world can now be found through the WorldLII Web site, and the sites of its member organizations. These projects have been strongly encouraged by the Free Access to Law Movement.

Many law librarians and academics have commented on the changing system of legal information delivery brought about by the rapid growth of the World Wide Web. Professor Bob Berring writes that the "primacy of the old paper sets [print law reports] is fading, and a vortex of conflicting claims and products is spinning into place".[5] In theory, court decisions posted on the Web expand access to the law beyond the specialized law library collections used primarily by lawyers and judges. The general public can more readily find court opinions online, whether posted on Web-accessible databases (such as the Hong Kong Judiciary public access site, above), or through general Web search engines.

Questions remain, however, on the need for a uniform and practical citation format for cases posted on the Web (versus the standard volume and page number used for print law reports).[5] Furthermore, turning away from the traditional "official-commercial" print report model raises questions about the accuracy, authority, and reliability of case law found on the Web.[5] The answer to these questions will be determined, in large part, through changing government information policies, and by the degree of influence exerted by commercial database providers on global legal information markets.

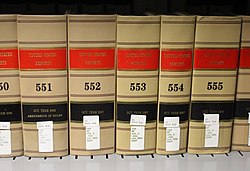

Design and cultural references

[edit]Reports usually come in the form of sturdy hardcover books with most of the design elements on the spine (the part that a lawyer would be most interested in when searching for a case). The volume number is usually printed in large type to make it easy to spot. Gold leaf is traditionally used on the spine for the name of the report and for some decorative lines and bars.

In lawyer portraits and advertisements, the rows of books visible behind the lawyer are usually reports.

History and case reporting (by country)

[edit]Canada

[edit]

Each province in Canada has an official reporter series that publishes superior court and appellate court decisions of the respective province. The federal courts, such as the Federal Court, Federal Court of Appeal, and Tax Court, each have their own reporter series. The Supreme Court of Canada has its own Reporter series, the Supreme Court Reports.

There are also general reporters, such as the long-running Dominion Law Reports, that publishes cases of national significance. Other law report series include the Canadian Criminal Cases, the Canadian Criminal Reports, the Ontario Reports and the Rapports Juridiques du Québec.[6][7]: 29

Neutral citations are also used to identify cases.[6]

United Kingdom

[edit]Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

[edit]The UK Supreme Court publishes on its own website the court's judgments after they have been handed down, together with the ICLR summary (or "headnote").[8]

England and Wales

[edit]

In England and Wales, beginning with the reports of cases contained in the Year Books (Edward II to Henry VIII) there are various sets of reports of cases decided in the higher English courts down to the present time. Until the nineteenth century, both the quality of early reports, and the extent to which the judge explained the facts of the case and his judgment, are highly variable, and the weight of the precedent may depend on the reputations of both the judge and the reporter. Such reports are now largely of academic interest, having been overtaken by statutes and later developments, but binding precedents can still be found, often most cogently expressed.[9]

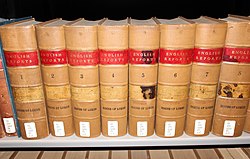

In 1865, the nonprofit Incorporated Council of Law Reporting (ICLR) for England and Wales was founded, and it has gradually become the dominant publisher of reports in the UK. It has compiled most of the best available copies of pre-1866 cases into the English Reports. Post-1865 cases are contained in the ICLR's own Law Reports. Even today, the UK government does not publish an official report, but its courts have promulgated rules stating that the ICLR reports must be cited when available.[10] Historical practice, which may still apply where no other report is available, permitted parties to rely on any report "with the name of a barrister annexed to it".[11]

English maritime law

[edit]While maritime cases often have a contract or tort element and are reported in the standard volumes, the standard source for maritime cases is the Lloyd's Law Reports, which covers matters including maritime matters such as carriage of goods by sea, international trade law, and admiralty law.

Scotland

[edit]The Session Cases report cases heard in the Court of Session and Scottish cases heard on appeal in the House of Lords. The Justiciary Cases report from the High Court of Justiciary. Those two series are the most authoritative and are cited in court in preference to other report series, such as the Scots Law Times, which reports sheriff court and lands tribunal cases in addition to the higher courts. The law reports service of Scotland is supplemented by other reports such as the Scottish Civil Case Reports and Green's Weekly Digest.

United States

[edit]

In each state of the United States, there are published reports of all cases decided by the courts having appellate jurisdiction going back to the date of their organization.[12][13] There are also complete reports of the cases decided in the United States Supreme Court and the inferior federal courts having appellate jurisdiction since their creation under the United States Constitution.[14] The early reporters were unofficial as they were published solely by private entrepreneurs, but in the middle of the 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court and many state supreme courts began publishing their own official reporters.

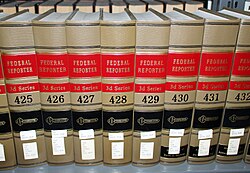

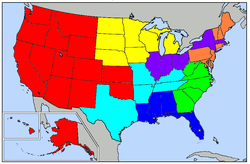

In the 1880s, the West Publishing Company started its National Reporter System (NRS), which is a family of regional reporters, each of which collects select state court opinions from a specific group of states.[12][15] The National Reporter System is now the dominant unofficial reporter system in the U.S., and 21 states have discontinued their own official reporters and certified the appropriate West regional reporter as their official reporter.[16] West and its rival, LexisNexis, both publish unofficial reporters of U.S. Supreme Court opinions. West also publishes the West American Digest System to help lawyers find cases in its reporters. West digests and reporters have always featured a "Key Numbering System" with a unique number for every conceivable legal topic.

The U.S. federal government does not publish an official reporter for the federal courts at the circuit and district levels.[17] However, just as the UK government uses the ICLR reporters by default, the U.S. courts use the unofficial West federal reporters for cases after 1880, which are the Federal Reporter (for courts of appeals) and the Federal Supplement (for district courts).[18] For cases from federal circuit and district courts prior to 1880, U.S. courts use Federal Cases.[17] The Federal Reporter, the Federal Supplement, and Federal Cases are all part of the NRS and include headnotes marked with West key numbers.[18] West's NRS also includes several unofficial state-specific reporters for large states like California.[15] The NRS now numbers well over 10,000 volumes;[12] therefore, only the largest law libraries maintain a full hard copy set in their on-site collections.

Some government agencies use (and require attorneys and agents practicing before them to cite to) certain unofficial reporters that specialize in the types of cases likely to be material to matters before the agency. For example, for both patent and trademark practice, the United States Patent and Trademark Office requires citation to the United States Patents Quarterly (USPQ).[19][20]

Today, both Westlaw and LexisNexis also publish a variety of official and unofficial reporters covering the decisions of many federal and state administrative agencies which possess quasi-judicial powers. A recent trend in American states is for bar associations to join a consortium called Casemaker. Casemaker gives members of a state bar access to a computerized legal research system.

Publications

[edit]- Eugene Wambaugh, Study of Cases (second edition, Boston, 1894)

- C. C. Soule, Lawyers' Reference Manual of Law Books and Citations (Boston, 1884)

- Stephen Elias and Susan Levinkind, Legal Research: How To Find And Understand The Law (Berkeley: Nolo Press, 2004)

Australia

[edit]

The Commonwealth Law Reports are the authorised reports of decision of the High Court of Australia. The Federal Court Reports are the authorised reports of decisions of the Federal Court of Australia (including the Full Court). Each state and territory has a series of authorised reports, e.g. the Victorian Reports, of decisions of the superior courts of the state or territory.

The Australian Law Reports are the largest series of unauthorised reports although there are several others general reports and reports relating to specific areas of the law, e.g. the Australian Torts Reports publish decisions from any state or federal court relating to tort law. The NSW Law Reports are published by the Council of Law Reporting for New South Wales and cover the Supreme Court of New South Wales. The Victorian Reports[21] are published by Little William Bourke[22] on behalf of the Council of Law Reporting in Victoria and cover the Supreme Court of Victoria.

New Zealand

[edit]The New Zealand Law Reports (NZLR) are the authorised reports of the New Zealand Council for Law Reporting and have been published continuously since 1883. The reports publish cases of significance from the High Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of New Zealand. The reports, which were initially sorted by volume, are sorted by year. Three volumes per year are now published, with the number of volumes having increased over time from one, to two and now to three. The reports do not focus on any particular area of law, with subject specific reports filling this niche. There are approximately 20 privately published report series focusing on specialist areas of law. Some areas are covered by more than one report series—such as employment, tax and family law.

Ireland

[edit]Most Irish law reports are contained in The Irish Reports (IR), published by the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for Ireland. Other reports are contained in the Irish Law Reports Monthly (ILRM) and various online collections of court decisions.

Bangladesh

[edit]In Bangladesh, the law reports are published according to the provisions of the Law Reports Act, 1875. There are many law reports now in Bangladesh. The most widely known being the Dhaka Law Report which started publication in 1949. Published monthly, the Apex Law Reports (ALR) provides timely treatment of significant developments in law through articles contributed by judges, leading scholars and practitioners. The Law Messenger[23] is an internationally standard law report which started publication in 2016. It is the first law journal in Bangladesh which specifically publishes law decisions of Supreme Court of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan only. Mainstream Law Reports (MLR)[24] is the most-cited law journal and it ranks among the country's most-cited law reviews of any kind. Published monthly, the MLR provides timely treatment of significant developments in law through articles contributed by judges, leading scholars and practitioners. Bangladesh Legal Decisions is published under the authority of the Bangladesh Bar Council. The other law reports include Bangladesh Law Chronicles, Lawyers and Jurists, BCR, ADC, Bangladesh Legal Times and Bangladesh Law Times.

The online law report in Bangladesh is Chancery Law Chronicles, which now publishes verdicts of Supreme Court of Bangladesh.[25]

After the Supreme Court of Bangladesh was established in 1972, its online law report is Supreme Court Online Bulletin[26] and it initially published a law report, containing the judgments, orders and decisions of the Court. Another widely used law report in the country is the Bangladesh Legal Decisions which is published by the official regulator of the enrolled lawyers of the country; the Bangladesh Bar Council. Various others for example, Bangladesh Law Chronicles, Bangladesh Legal Times, Lawyers and Jurists, Counsel Law Reports, Legal Circle Law Reports, Bangladesh Legal Times, BCR, ADC are also in operation. The decisions of the lower judiciary are not reported in any law report.

India

[edit]The Supreme Court Reports (SCR) is the official reporter for Supreme Court decisions. In addition, some private reporters have been authorised to publish the Court's decisions.[citation needed]

Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan inherited a common law system upon independence from Great Britain in 1947, and thus its legal system relies heavily on law reports.

The most comprehensive law book is the "Pakistan Law Decisions" (PLD), which contains judgments from the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the various provincial High Courts, the Service, Professional and Election Tribunals as well as the superior courts of territories such as Azad Kashmir. PLD is augmented by other books, most notably the "Yearly Law Reports" (YLR), and the "Monthly Law Digest" (MLD).

The Supreme Court also has its own law book, the "Supreme Court Monthly Review" (SCMR), which lists more recent cases that the appex court heard.

In addition, there are books dealing with specific areas of law, such as the "Civil Law Cases" (CLC), which as the name suggests deals with Civil cases; the "Pakistan Criminal Law Journal" (PCrLJ), which reports Criminal Cases; and the "Pakistan Tax Decisions" (PTD), on the Income Tax tribunal cases and their appeals.

Kenya

[edit]Kenya's first output of law reports was in the form of volumes under the citation E.A.L.R (East African Law Reports). They were first published between 1897 and 1905. Seven of these volumes were compiled by the Hon Mr Justice R. W. Hamilton, who was then the Chief Justice of the Protectorate and the reports covered all courts of different jurisdictions.

The 1922–1956 period saw the emergence of some twenty-one volumes of the Kenya Law Reports (under the citation K.L.R). These reports included the decisions of the High Court only and were collated, compiled and edited by different puisne judges and magistrates.

Then came the period covering 1934 to 1956 which saw the birth of the famous Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa Law Reports (E.A.L.R). These reports comprised twenty-three volumes altogether which were also compiled by puisne judges and magistrates, a Registrar of the High Court and a Registrar of the Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa. These volumes reported the decisions of the then Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa and of the Privy Council. They covered only those appeals filed from the territories.

The East Africa Law Reports (cited as E.A.) were introduced in 1957 and were published in nineteen consecutive volumes until 1975. These reports covered decisions of the Court of Appeal for East Africa and the superior courts of the constituent territories, namely, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Aden, Seychelles and Somaliland. They were published under an editorial board consisting of the Chief Justices of the Territories and the presiding judge of the Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa. Following the collapse of the East African Community, under whose auspices the reports were published, the reports went out of publication.

The period before the resumption of the East Africa Law Reports saw sporadic and transitory attempts at law reporting. Firstly, with the authority of the then Attorney-General, six volumes named the New Kenya Law Reports covering the period between and including the years 1976 to 1980 were published by the East African Publishing House. These reports included the decisions of the High Court and Court of Appeal of Kenya and were compiled by the Late Hon Mr Justice S. K. Sachdeva and were edited by Mr Paul H Niekirk and the Hon Mr Justice Richard Kuloba, a judge of the High Court of Kenya. The publication of these reports ceased when the publishing house folded them up ostensibly on account of lack of funds.

Later, two volumes of what were known as the Kenya Appeal Reports were published for the period 1982–1992 by Butterworths, a private entity, under the editorship of The Hon Chief Justice A.R.W. Hancox (hence the pseudonym "Hancox Reports") who had the assistance of an editorial board of seven persons. These reports, as their name suggested, included only the decisions of the Court of Appeal of Kenya selected over that period.

Law reports relating to special topics have also been published. Ten volumes of the Court of Review Law Reports covering the period 1953 to 1962 and including the decisions on customary law by the African Court of Review were published by the Government Printer. There was no editorial board and it is not known who the compilers of these reports were. Their apocryphal origin notwithstanding, they were commonly cited by legal practitioners and scholars.

In 1994, the Kenyan Parliament passed the National Council for Law Reporting Act, 1994 and gave the Council the exclusive mandate of: "publication of the reports to be known as the Kenya Law Reports which shall contain judgments, rulings and opinions of the superior courts of record and also undertake such other publications as in the opinion of the Council are reasonably related to or connected with the preparation and publication of the Kenya Law Reports" (section 3 of the Act).

The Kenya Law Reports are the official law reports of the Republic of Kenya which may be cited in proceedings in all courts of Kenya (section 21 of the Act).

Hong Kong

[edit]Cases of Hong Kong are predominantly published in the authorised Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal Reports (HKCFAR) and Hong Kong Law Reports and Digests (HKLRD), as well as the unauthorised but the oldest Hong Kong Cases (HKC). Some specialist series are available including the Hong Kong Family Law Reports (HKFLR), Hong Kong Public Law Reports (HKPLR) and Conveyancing and Property Reports (CPR). Chinese-language judgments are published in the Hong Kong Chinese Law Reports and Translation (HKCLRT). The Hong Kong Law Reports and Digests were published as the Hong Kong Law Reports (HKLR) until 1997.

See also

[edit]- All England Law Reports

- Atlantic Reporter

- European Patent Office Reports (EPOR)

- North Eastern Reporter

- North Western Reporter

- Pacific Reporter

- South Eastern Reporter

- Southern Reporter

- South Western Reporter

References

[edit]- ^ Friedman, Lawrence M. (2019). A History of American Law (4th ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 308–310. ISBN 9780190070915. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Putman, William H.; Albright, Jennifer R. (2014). Legal Research (3rd ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. p. 138. ISBN 9781305147188. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Harvard Law School Library, One-L Dictionary, definition for 'Official Publications'". Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (24 May 2014). "Final Word on U.S. Law Isn't: Supreme Court Keeps Editing". New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Berring, Bob (Spring 1997). "Chaos, Cyberspace and Tradition: Legal Information Transmogrified" (PDF). Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 12: 189 at 200–203. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2015..

- ^ a b "Case law: online resources for common law countries: Canada". Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Guide to Foreign and International Legal Citations law.nyu.edu

- ^ Court, The Supreme. "Decided cases – The Supreme Court". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ W. T. S. Daniel, History of the Origin of the Law Reports (London, 1884)

- ^ Lord Judge CJ, Practice Direction (Citation of Authorities) [2012] 1 WLR 780 [6]. Archived 2015-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MacQueen QC, John Fraser, ed. (12 June 1863). Speech of the Lord Chancellor on the Revision of the Law. London: W. Maxwell. p. 9.

The reports are published without any judicial control or sanction, nor is there any provision to secure correctness or security against error, but as soon as a report is published of any case with the name of a barrister annexed to it the report is accredited, and may be cited as an authority before any tribunal.

- ^ a b c Farnsworth, E. Allan (2010). Sheppard, Steve (ed.). An Introduction to the Legal System of the United States (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780199733101.

- ^ Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ a b Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ a b Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ a b Barkan, Steven M.; Bintliff, Barbara A.; Whisner, Mary (2015). Fundamentals of Legal Research (10th ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1609300562.

- ^ Citation of authority, 37 C.F.R. § 42.12(a)(2) Archived 2007-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Citation of Decisions and Office Publications, Trademark Manual of Examination Procedures § 705.05 Archived 2008-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Victorian Reports". Archived from the original on 10 May 2017.

- ^ "Little William Bourke". Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Editorial Team, Judges Name & Others". Archived from the original on 16 April 2017.

- ^ "Appellate Division Civil". www.mlrbd.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011.

- ^ Rahman, S.M. Saidur. "Chancery Law Chronicles – Online Database of Bangladesh Laws". Archived from the original on 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Home : Supreme Court of Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 21 December 2010.

Source note

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "yes". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "yes". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.