The Big Sleep

First-edition cover | |

| Author | Raymond Chandler |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Philip Marlowe |

| Genre | Hardboiled detective, crime |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date | 1939 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 277 |

| OCLC | 42659496 |

| Followed by | Farewell, My Lovely |

The Big Sleep (1939) is a hardboiled crime novel by American-British writer Raymond Chandler, the first to feature the detective Philip Marlowe. It has been adapted for film twice, in 1946 and again in 1978. The story is set in Los Angeles.

The story is noted for its complexity, with characters double-crossing one another and secrets being exposed throughout the narrative. The title is a euphemism for death; the final pages of the book refer to a rumination about "sleeping the big sleep".

In 1999, the book was voted 96th of Le Monde's "100 Books of the Century". In 2005, it was included in Time magazine's "List of the 100 Best Novels".[1]

Plot

[edit]Private investigator Philip Marlowe is called to the home of the wealthy and elderly General Sternwood. He wants Marlowe to deal with an attempt by a bookseller named Arthur Geiger to blackmail his wild young daughter, Carmen. She had previously been blackmailed by a man named Joe Brody. Sternwood mentions that his other, older daughter Vivian is in a loveless marriage with a man named Rusty Regan, who has disappeared. On Marlowe's way out, Vivian wonders if he was hired to find Regan, but Marlowe will not say.

Marlowe investigates Geiger's bookstore and meets Agnes, the clerk. He determines that the store is an illegal pornography lending library. He follows Geiger home, stakes out his house, and sees Carmen enter. Later, he hears a scream, followed by gunshots and two cars speeding away. He rushes in to find Geiger dead and Carmen drugged and naked, in front of an empty camera. He takes her home but when he returns, Geiger's body is gone. He quickly leaves. The next day, the police call him and let him know the Sternwoods' car was found driven off a pier, with their chauffeur dead inside. It appears that he was hit on the head before the car entered the water. The police also ask if Marlowe is looking for Regan.

Marlowe stakes out the bookstore and sees its inventory being moved to Brody's home. Vivian comes to his office and says Carmen is being blackmailed with the nude photos from the previous night. She also mentions gambling at the casino of Eddie Mars and volunteers that Eddie's wife, Mona, ran off with Rusty. Marlowe revisits Geiger's house and finds Carmen trying to get in. They look for the photos, but she plays dumb about the night before. Eddie suddenly enters; he says he is Geiger's landlord and is looking for him. Eddie demands to know why Marlowe is there; Marlowe takes no notice and states that he is no threat to him.

Marlowe goes to Brody's home and finds him with Agnes, the bookstore clerk. Marlowe tells Brody that he knows they are taking over the lending library and blackmailing Carmen with the nude photos. Carmen forces her way in with a gun and demands the photos, but Marlowe takes her gun and makes her leave. Marlowe interrogates Brody further and pieces together the story: Geiger was blackmailing Carmen; the family driver, Owen Taylor, did not like it and so he snuck in and killed Geiger, then took the film of Carmen. Brody was staking out the house too and pursued the driver, knocked him out, stole the film, and possibly pushed the car off the pier. (In the novel, one investigator suggests that the chauffeur may have committed suicide. He had been rejected by Carmen, killed Carmen's pornographic exploiter, then drove off the pier intentionally.) Suddenly, the doorbell rings and Brody is shot dead; Marlowe gives chase and catches Geiger's male lover, Carol Lundgren, who shot Brody thinking he had killed Geiger. He had also hidden Geiger's body, so he could remove his own belongings before the police got wind of the murder.

The case is over, but Marlowe is nagged by Rusty’s disappearance. The police accept that he simply ran off with Mona, since she is also missing, and since Eddie would not risk committing a murder in which he would be the obvious suspect. Mars calls Marlowe to his casino and seems to be nonchalant about everything. Vivian is also there, and Marlowe senses something between her and Mars. He drives her home and she tries to seduce him, but he rejects her advances. When he gets home, he finds Carmen has snuck into his bed, and he rejects her, too.

A man named Harry Jones, who is Agnes's new partner, approaches Marlowe and offers to tell him the location of Mona. Marlowe plans to meet him later, but Eddie’s henchman, Lash Canino, is suspicious of Jones and Agnes's intentions, and kills Jones first. Marlowe manages to meet Agnes anyway and receives the information. He goes to the location in Realito, a repair shop with a home at the back, but Canino – with the help of Art Huck, the garage man – jumps him and knocks him out. When Marlowe awakens, he is tied up, and Mona is there with him. She says she has not seen Rusty in months; she only hid out to help Eddie and insists he did not kill Rusty. She frees Marlowe, and he shoots and kills Canino.

The next day, Marlowe visits General Sternwood, who remains curious about Rusty's whereabouts and offers Marlowe an additional $1,000 fee if he is able to locate him. On the way out, Marlowe returns Carmen's gun to her, and she asks him to teach her how to shoot. They go to an abandoned field, where she tries to kill him, but he has loaded the gun with blanks and merely laughs at her; the shock causes Carmen to have an epileptic seizure. Marlowe brings her back and tells Vivian he has guessed the truth: Carmen came on to Rusty and he spurned her, so she killed him. Eddie, who had been backing Geiger, helped Vivian conceal it by helping to dispose of Rusty's body, inventing a story about his wife running off with Rusty, and then blackmailing her himself. Vivian says she did it to keep it all from her father, so he would not despise his own daughters, and promises to have Carmen institutionalised.

With the case now over, Marlowe goes to a local bar and orders several double Scotches. While drinking, he begins to think about Mona "Silver-Wig" Mars, but never sees her again.

Background

[edit]The Big Sleep, like most of Chandler's novels, was written by what he called "cannibalizing" his short stories.[2] Chandler would take stories he had already published in the pulp magazine Black Mask and rework them into a coherent novel. For The Big Sleep, the two main stories that form the core of the novel are "Killer in the Rain" (published in 1935) and "The Curtain" (published in 1936). Although the stories were independent and shared no characters, they had some similarities that made it logical to combine them. In both stories there is a powerful father who is distressed by his wayward daughter. Chandler merged the two fathers into a new character and did the same for the two daughters, resulting in General Sternwood and his wild daughter Carmen. Chandler also borrowed small parts of two other stories, "Finger Man" and "Mandarin's Jade".[3]

This process — especially in a time when cutting and pasting was done by cutting and pasting paper — sometimes produced a plot with a few loose ends. An unanswered question in The Big Sleep is who killed the chauffeur. When Howard Hawks filmed the novel, his writing team was perplexed by that question, in response to which Chandler replied that he had no idea.[4] This exemplifies a difference between Chandler's style of crime fiction and that of previous authors. To Chandler, plot was less important than atmosphere and characterisation. An ending that answered every question while neatly tying every plot thread mattered less to Chandler than interesting characters with believable behaviour.

When Chandler merged his stories into a novel, he spent more effort on expanding descriptions of people, places, and Marlowe's thinking than getting every detail of the plot perfectly consistent. In "The Curtain", the description of Mrs. O'Mara's room is just enough to establish the setting:

This room had a white carpet from wall to wall. Ivory drapes of immense height lay tumbled casually on the white carpet inside the many windows, which stared towards the dark foot-hills. The air beyond the glass was dark too. It had not started to rain, yet there was a feeling of pressure in the atmosphere.

In The Big Sleep, Chandler expanded this description of the room and used new detail (e.g. the contrast of white and "bled out", the coming rain) to foreshadow the fact that Mrs. Regan (Mrs. O'Mara in the original story) is covering up the murder of her husband by her sister and that the coming rainstorm will bring more deaths:

The room was too big, the ceiling was too high, the doors were too tall, and the white carpet that went from wall to wall looked like a fresh fall of snow at Lake Arrowhead. There were full-length mirrors and crystal doodads all over the place. The ivory furniture had chromium on it, and the enormous ivory drapes lay tumbled on the white carpet a yard from the windows. The white made the ivory look dirty and the ivory made the white look bled out. The windows stared towards the darkening foothills. It was going to rain soon. There was pressure in the air already.[5]

Of the historical plausibility of Geiger's character, Jay A. Gertzman wrote:

Erotica dealers with experience had to be tough, although not necessarily predatory, and the business was not for the timid or scrupulous. But the criminality of erotica dealers did not extend beyond bookselling into organized racketeering; Al Capone and Meyer Lansky were not role models. A figure like A. G. Geiger, the dirty-books racketeer in Raymond Chandler's Big Sleep (1939) who supplements his business activities as owner of a pornographic lending library in Hollywood by arranging sex orgies and blackmailing rich customers, is a fascinating but lurid exaggeration. However susceptible film personalities were to blackmail, it was not the métier of book dealers.[6]

The Big Sleep takes place in the 1930s, and thus its story was also largely influenced by the very real massive social upheaval during the interwar period. During the harsh 1930s, the American people lost much faith in the government due to their repeated intervention failures, experienced the rise of gang violence from Prohibition, and endured the severe decline of public welfare from disasters such as the Great Depression and Dust Bowl.[7] Chandler himself was fired from his job at an oil company in 1932, which would lead him to begin writing in the grittier and more cynical hard-boiled genre that mirrored the hardships of its time. In American essayist Herbert Ruhm's introduction to the Black Mask, a hard-boiled magazine that Chandler initially wrote for, Ruhm found that: "...the streets of the cities best reflected the moral disorder of the era. Events were depicted in language of these streets; mean, slangy, prejudiced, sometimes witty and always tough."[8]

Through this time of suffering, people began flocking towards big cities such as Los Angeles—also the setting of The Big Sleep—for work, which consequently made cities hotspots for the new meshing of demographic and socioeconomic changes. As a result, roots of modernity and mass culture began to form in America, slowly eroding old social norms such as the traditional views of masculinity and family. This plays heavily into Chandler's depiction of Marlowe as a chivalrous lone wolf of the old guard, futilely trying to change the world around him.

Themes

[edit]Masculinity is at the very core of The Big Sleep. In the very beginning of the novel, Chandler already sets up the masculine characterization of Marlowe when he observes a stained-glass panel portraying a knight attempting to rescue a damsel in distress. Readers have interpreted Marlowe's self-identification with the knight as illustrating a conformity to the chivalrous old views of masculinity. His disdain for queer relationships, such as with Geiger and Lundgren, sheds more light on what delineates Marlowe's masculinity as strictly conforming to the heteronormative perspective.[7]

Marlowe's loyalty to the Sternwoods also caused readers to make connections to themes of family hierarchies and relations. Marlowe's isolation hangs over the entire novel, and readers have inferred that Marlowe's close dedication to his client is his implicit desire to be part of a family, citing Marlowe's continued use of "we" in interrogating suspects as his attempt to integrate himself into the family.[9]

Adaptations

[edit]

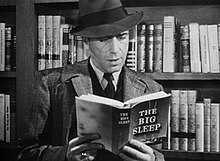

- The Big Sleep, a 1946 film starring Humphrey Bogart and directed by Howard Hawks

- Television adaptation by Richard Morrison, directed by Norman Felton and starring Zachary Scott, broadcast on 25 September 1950

- The Big Sleep, a 1978 film starring Robert Mitchum and directed by Michael Winner

- Adaptation for radio by Bill Morrison, directed by John Tydeman, and broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 26 September 1977, starring Ed Bishop as Marlowe

- Another adaptation by BBC Radio 4, directed by Claire Grove and broadcast on 5 February 2011, starring Toby Stephens as Marlowe

- Perchance to Dream, Robert B. Parker's authorised 1990 sequel

- The Coen brothers' film The Big Lebowski was inspired by the character Philip Marlowe and the style and plot elements of Chandler's novels such as The Big Sleep.[10][11]

- The Big Sleep, a stage adaptation by Alvin Rakoff and John D. Rakoff, premièred in October 2011 at The Mill at Sonning, Berkshire, UK. Dan Chameroy played Marlowe.

Critical reception

[edit]The Big Sleep has achieved critical acclaim. On November 5, 2019, the BBC News listed The Big Sleep on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[12] In a 2014 retrospective, The Guardian ranked it No. 62 on its list of the 100 best novels.[13] The book review site The Pequod rated the book a 9.5 (out of 10.0), saying, "This is one of Raymond Chandler's best books … The real pleasures lie not in the story, but in Chandler's atmospheric settings."[14] The New York Times also praised the book: "As a study in depravity, the story is excellent, with Marlowe standing out as almost the only fundamentally decent person in it."[15]

References

[edit]- ^ "All Time 100 Novels". Time. 16 October 2005. Archived from the original on 22 October 2005. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ MacShane, Frank (1976). The Life of Raymond Chandler. New York: E.P. Dutton. pp. 67. ISBN 0-525-14552-4.

- ^ MacShane, Frank (1976). The Life of Raymond Chandler. New York: E.P. Dutton. pp. 68. ISBN 0-525-14552-4.

- ^ Letter to Jamie Hamilton, 21 March 1949. In Hiney, T. and MacShane, F. (2000). The Raymond Chandler Papers. Atlantic Monthly Press p. 105.

- ^ MacShane, Frank (1976). The Life of Raymond Chandler. New York: E.P. Dutton. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-525-14552-4.

- ^ Gertzman, Jay A. (1999). Bookleggers and Smuthounds: The Trade in Erotica 1920–1940 (First paperback printing, 2002 ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-8122-1798-5.

- ^ a b Snyder, Robert Lance (22 March 2018). ""Arabesques of the Final Pattern": Len Deighton's Hard-Boiled Espionage Fiction". Papers on Language & Literature. 54 (2): 155–187.

- ^ ZINSSER, DAVID LOWE. WATCHING THE DETECTIVE (A LITERARY ANALYSIS OF THE WORKS OF RAYMOND CHANDLER). 1982. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- ^ Beal, Wesley (2014). "Philip Marlowe, Family Man". College Literature. 41 (2): 11–28. doi:10.1353/lit.2014.0021. ISSN 1542-4286.

- ^ IndieWire, "An Interview with The Coen Brothers, Joel and Ethan about The Big Lebowski," 1998

- ^ IndieWire, "The Coens Speak (Reluctantly)", March 9, 1998 (retrieved 7 January 2010)

- ^

"100 'most inspiring' novels revealed by BBC Arts". BBC News. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

The reveal kickstarts the BBC's year-long celebration of literature.

- ^ "The 100 best novels: No 62 – The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939)". The Guardian. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "The Big Sleep | The Pequod". the-pequod.com. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ "New Mystery Stories". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Phillips, Gene D. (2000). Creatures of Darkness: Raymond Chandler, Detective Fiction, and Film Noir. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9042-8.

External links

[edit]- The Big Sleep at Faded Page (Canada)

- Marling, William. "Major Works: The Big Sleep, by Rayond Chandler".

- The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler: A book review

- "Killer in the Rain" (1935), Chandler short story Archived 18 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Curtain" (1936), Chandler short story Archived 20 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- 1930s LGBTQ novels

- 1939 American novels

- 1939 debut novels

- Alfred A. Knopf books

- American detective novels

- American novels adapted into films

- British novels adapted into films

- Euphemisms

- First-person narrative novels

- Hardboiled crime novels

- Novels by Raymond Chandler

- Novels set in Los Angeles

- Philip Marlowe novels