Blacktip shark

| Blacktip shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. limbatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus limbatus (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1839)

| |

| |

| Range of the blacktip shark | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

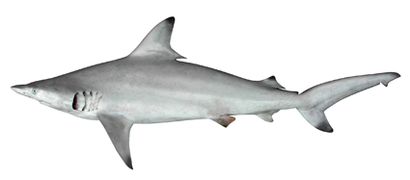

The blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae. It is common to coastal tropical and subtropical waters around the world, including brackish habitats. Genetic analyses have revealed substantial variation within this species, with populations from the western Atlantic Ocean isolated and distinct from those in the rest of its range. The blacktip shark has a stout, fusiform body with a pointed snout, long gill slits, and no ridge between the dorsal fins. Most individuals have black tips or edges on the pectoral, dorsal, pelvic, and caudal fins. It usually attains a length of 1.5 m (4.9 ft).

Swift, energetic piscivores, blacktip sharks are known to make spinning leaps out of the water while attacking schools of small fish. Their demeanor has been described as "timid" compared to other large requiem sharks. Both juveniles and adults form groups of varying size. Like other members of its family, the blacktip shark is viviparous; females bear one to 10 pups every other year. Young blacktip sharks spend the first months of their lives in shallow nurseries, and grown females return to the nurseries where they were born to give birth themselves. In the absence of males, females are also capable of asexual reproduction.

Normally wary of humans, blacktip sharks can become aggressive in the presence of food and have been responsible for a number of attacks on people. This species is of importance to both commercial and recreational fisheries across many parts of its range, with its meat, skin, fins, and liver oil used. It has been assessed as Vulnerable by the IUCN, on the basis of its low reproductive rate and high value to fishers.

Taxonomy

[edit]The blacktip shark was first described by French zoologist Achille Valenciennes as Carcharias (Prionodon) limbatus in Johannes Müller and Friedrich Henle's 1839 Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen. The type specimens were two individuals caught off Martinique, both of which have since been lost. Later authors moved this species to the genus Carcharhinus.[2][3] The specific epithet limbatus is Latin for "bordered", referring to the black edges of this shark's fins.[4] Other common names used for the blacktip shark include blackfin shark, blacktip whaler, common or small blacktip shark, grey shark, and spotfin ground shark.[5]

Phylogeny and evolution

[edit]The closest relatives of the blacktip shark were originally thought to be the graceful shark (C. amblyrhynchoides) and the spinner shark (C. brevipinna), due to similarities in morphology and behavior. However, this interpretation has not been borne out by studies of mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA, which instead suggest affinity with the blacknose shark (C. acronotus). More work is required to fully resolve the relationship between the blacktip shark and other Carcharhinus species.[6]

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA has also revealed two distinct lineages within this species, one occupying the western Atlantic and the other occupying the eastern Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. This suggests that Indo-Pacific blacktip sharks are descended from those in the eastern Atlantic, while the western Atlantic sharks became isolated by the widening Atlantic Ocean on one side and the formation of the Isthmus of Panama on the other. Blacktip sharks from these two regions differ in morphology, coloration, and life history characteristics, and the eastern Atlantic lineage may merit species status.[7] Fossil teeth belonging to this species have been found in Early Miocene (23–16 Ma) deposits in Delaware and Florida.[8][9]

Description

[edit]The blacktip shark has a robust, streamlined body with a long, pointed snout and relatively small eyes. The five pairs of gill slits are longer than those of similar requiem shark species.[2] The jaws contain 15 tooth rows on either side, with two symphysial teeth (at the jaw midline) in the upper jaw and one symphysial tooth in the lower jaw. The teeth are broad-based with a high, narrow cusp and serrated edges.[3] The first dorsal fin is tall and falcate (sickle-shaped) with a short free rear tip; no ridge runs between the first and second dorsal fins. The large pectoral fins are falcate and pointed.[2]

The coloration is gray to brown above and white below, with a conspicuous white stripe running along the sides. The pectoral fins, second dorsal fin, and the lower lobe of the caudal fin usually have black tips. The pelvic fins and rarely the anal fin may also be black-tipped. The first dorsal fin and the upper lobe of the caudal fin typically have black edges.[2] Some larger individuals have unmarked or nearly unmarked fins.[4] Blacktip sharks can temporarily lose almost all their colors during blooms, or "whitings", of coccolithophores.[10] This species attains a maximum known length of 2.8 m (9.2 ft), though 1.5 m (4.9 ft) is more typical, and a maximum known weight of 123 kg (271 lb).[5]

-

The blacktip shark has black markings on most of its fins.

-

Lower teeth

-

Upper teeth

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The blacktip shark has a worldwide distribution in tropical and subtropical waters. In the Atlantic, it is found from Massachusetts to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, and from the Mediterranean Sea, Madeira, and the Canary Islands to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It occurs all around the periphery of the Indian Ocean, from South Africa and Madagascar to the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent, to Southeast Asia. In the western Pacific, it is found from the Ryukyu Islands of Japan[11] to northern Australia, including southern China, the Philippines and Indonesia. In the eastern Pacific, it occurs from Southern California to Peru. It has also been reported at a number of Pacific islands, including New Caledonia, Tahiti, the Marquesas, Hawaii, Revillagigedo, and the Galápagos.[2]

Most blacktip sharks are found in water less than 30 m (98 ft) deep over continental and insular shelves, though they may dive to 64 m (210 ft).[5] Favored habitats are muddy bays, island lagoons, and the drop-offs near coral reefs; they are also tolerant of low salinity and enter estuaries and mangrove swamps. Although an individual may be found some distance offshore, blacktip sharks do not inhabit oceanic waters.[2] Seasonal migration has been documented for the population off the east coast of the United States, moving north to North Carolina in the summer and south to Florida in the winter.[12]

Biology and ecology

[edit]The blacktip shark is an extremely fast, energetic predator that is usually found in groups of varying size.[4] Segregation by sex and age does not occur; adult males and nonpregnant females are found apart from pregnant females, and both are separated from juveniles.[2] In Terra Ceia Bay, Florida, a nursery area for this species, juvenile blacktips form aggregations during the day and disperse at night. They aggregate most strongly in the early summer when the sharks are youngest, suggesting that they are seeking refuge from predators (mostly larger sharks) in numbers.[13] Predator avoidance may also be the reason why juvenile blacktips do not congregate in the areas of highest prey density in the bay.[14] Adults have no known predators.[3] Known parasites of the blacktip shark include the copepods Pandarus sinuatus and P. smithii, and the monogeneans Dermophthirius penneri and Dionchus spp., which attach the shark's skin.[3][15][16] This species is also parasitized by nematodes in the family Philometridae (genus Philometra), which infest the ovaries.[17]

Behaviour

[edit]

Like the spinner shark, the blacktip shark is known to leap out of the water and spin three or four times about its axis before landing. Some of these jumps are the end product of feeding runs, in which the shark corkscrews vertically through schools of small fish and its momentum launches it into the air.[4] Observations in the Bahamas suggest that blacktip sharks may also jump out of the water to dislodge attached sharksuckers, which irritate the shark's skin and compromise its hydrodynamic shape.[18] The speed attained by the shark during these jumps has been estimated to average 6.3 m/s (21 ft/s).[19]

Blacktip sharks have a timid disposition and consistently lose out to Galapagos sharks (C. galapagensis) and silvertip sharks (C. albimarginatus) of equal size when competing for food.[2] If threatened or challenged, they may perform an agonistic display: the shark swims towards the threat and then turns away, while rolling from side to side, lowering its pectoral fins, tilting its head and tail upwards, and making sideways biting motions. The entire sequence lasts around 25 seconds. This behavior is similar to the actions of a shark attempting to move a sharksucker; one of these behaviors possibly is derived from the other.[20]

Feeding

[edit]Fish make up some 90% of the blacktip shark's diet.[21] A wide variety of fish have been recorded as prey for this species: sardines, menhaden, herring, anchovies, ladyfish, sea catfish, cornetfish, flatfish, threadfins, mullet, mackerel, jacks, groupers, snook, porgies, mojarras, emperors, grunts, butterfish, croakers, soles, tilapia, triggerfish, boxfish, and porcupinefish.[22] They also feed on rays and skates, as well as smaller sharks such as smoothhounds and sharpnose sharks. Rays, crustaceans, and cephalopods are occasionally taken.[2][22] In the Gulf of Mexico, the most important prey of the blacktip shark is the Gulf menhaden (Brevoortia patronus), followed by the Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulatus).[21] Off South Africa, jacks and herring are the most important prey.[23] Hunting peaks at dawn and dusk.[21] The excitability and sociability of blacktip sharks makes them prone to feeding frenzies when large quantities of food are suddenly available, such as when fishing vessels dump their refuse overboard.[2]

Life history

[edit]As with other requiem sharks, the blacktip shark is viviparous. Females typically give birth to four to seven (range one to 10) pups every other year, making use of shallow coastal nurseries that offer plentiful food and fewer predators.[2] Known nurseries include Pine Island Sound, Terra Ceia Bay, and Yankeetown along the Gulf Coast of Florida, Bulls Bay on the coast of South Carolina, and Pontal do Paraná on the coast of Brazil.[24][25] Although adult blacktip sharks are highly mobile and disperse over long distances, they are philopatric and return to their original nursery areas to give birth. This results in a series of genetically distinct breeding stocks that overlap in geographic range.[24][26]

Mating occurs from spring to early summer, and the young are born around the same time the following year after a gestation period of 10–12 months.[2] Females have one functional ovary and two functional uteri; each uterus is separated into compartments with a single embryo inside each.[27] The embryos are initially sustained by a yolk sac; in the 10th or 11th week of gestation, when the embryo measures 18–19 cm long (7.1–7.5 in), the supply of yolk is exhausted and the yolk sac develops into a placental connection that sustains the embryo until birth.[12] The length at birth is 55–60 cm (22–24 in) off the eastern United States and 61–65 cm (24–26 in) off North Africa.[12][27] The mortality rate in the first 15 months of life is 61–91%, with major threats being predation and starvation.[28] The young remain in the nurseries until their first fall, when they migrate to their wintering grounds.[12]

The growth rate of this species slows with age: 25–30 cm (9.8–11.8 in) in the first six months, then 20 cm (7.9 in) a year until the second year, then 10 cm (3.9 in) a year until maturation, then 5 cm (2.0 in) a year for adults.[29][30] The size at maturity varies geographically: males and females mature at 1.4–1.5 m (4.6–4.9 ft) and 1.6 m (5.2 ft), respectively, in the northeastern Atlantic,[12] 1.3–1.4 m (4.3–4.6 ft) and 1.5–1.6 m (4.9–5.2 ft), respectively, in the Gulf of Mexico,[29][31] 1.5 and 1.6 m (4.9 and 5.2 ft) respectively off South Africa,[32] and 1.7 and 1.8 m (5.6 and 5.9 ft), respectively, off North Africa.[27] The age at maturation is 4–5 years for males and 7–8 years for females.[29][31] The lifespan is at least 12 years.[2]

In 2007, a 9-year-old female blacktip shark at the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center was found to be pregnant with a single near-term female pup, despite having never mated with a male. Genetic analysis confirmed that her offspring was the product of automictic parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction in which an ovum merges with a polar body to form a zygote without fertilization. Along with an earlier case of parthenogenesis in the bonnethead (Sphyrna tiburo), this event suggests that asexual reproduction may be more widespread in sharks than previously thought.[33]

Human interactions

[edit]

Blacktip sharks showing curiosity towards divers has been reported, but they remain at a safe distance. Under most circumstances, these timid sharks are not regarded as highly dangerous to humans. However, they may become aggressive in the presence of food, and their size and speed invite respect.[2] As of 2008, the International Shark Attack File lists 28 unprovoked attacks (one fatal) and 13 provoked attacks by this species.[34] Blacktip sharks are responsible annually for 16% of the shark attacks around Florida. Most attacks by this species result in only minor wounds.[3]

As one of the more common large sharks in coastal waters, the blacktip shark is caught in large numbers by commercial fisheries throughout the world, using longlines, fixed-bottom nets, bottom trawls, and hook-and-line. The meat is of high quality and marketed fresh, frozen, or dried and salted. In addition, the fins are used for shark fin soup, the skin for leather, the liver oil for vitamins, and the carcasses for fishmeal.[2] Blacktip sharks are one of the most important species to the northwestern Atlantic shark fishery, second only to the sandbar shark (C. plumbeus). The flesh is considered superior to that of the sandbar shark, resulting in the sandbar and other requiem shark species being sold under the name "blacktip shark" in the United States. The blacktip shark is also very significant to Indian and Mexican fisheries, and is caught in varying numbers by fisheries in the Mediterranean and South China Seas, and off northern Australia.[30]

The blacktip shark is popular with recreational anglers in Florida, the Caribbean, and South Africa. It is listed as a game fish by the International Game Fish Association. Once hooked, this species is a strong, steady fighter that sometimes jumps out of the water.[3] Since 1995, the number of blacktip sharks taken by recreational anglers in the United States has approached or surpassed the number taken by commercial fishing.[30] The International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed the blacktip shark as Vulnerable, as its low reproductive rate renders it vulnerable to overfishing.[1] The United States and Australia are the only two countries that manage fisheries catching blacktip sharks. In both cases, regulation occurs under umbrella management schemes for multiple shark species, such as that for the large coastal sharks category of the US National Marine Fisheries Service Atlantic shark Fisheries Management Plan. No conservation plans specifically for this species have been implemented.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Rigby, C.L.; Carlson, J.; Chin, A.; Derrick, D.; Dicken, M.; Pacoureau, N. (2021). "Carcharhinus limbatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T3851A2870736. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T3851A2870736.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. pp. 481–483. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Curtis, T. Biological Profiles: Blacktip Shark Archived 2007-06-29 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on April 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, D.A. (2003). Sharks, Rays, and Chimaeras of California. London: University of California Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-520-23484-0.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Carcharhinus limbatus". FishBase. April 2009 version.

- ^ Dosay-Akbulut, M. (2008). "The phylogenetic relationship within the genus Carcharhinus". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 331 (7): 500–509. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2008.04.001. PMID 18558373.

- ^ Keeney, D.B. & Heist, E.J. (October 2006). "Worldwide phylogeography of the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) inferred from mitochondrial DNA reveals isolation of western Atlantic populations coupled with recent Pacific dispersal". Molecular Ecology. 15 (12): 3669–3679. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03036.x. PMID 17032265. S2CID 24521217.

- ^ Benson. R.N., ed. (1998). Geology and Paleontology of the Lower Miocene Pollack Farm Fossil Site, Delaware: Delaware Geological Survey Special Publication No. 21. Delaware Natural History Survey. pp. 133–139.

- ^ Brown, R.C. (2008). Florida's Fossils: Guide to Location, Identification, and Enjoyment (third ed.). Pineapple Press Inc. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-56164-409-4.

- ^ Martin, R.A. Albinism in Sharks. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 28, 2009.

- ^ Yano, Kazunari; Morrissey, John F. (1999-06-01). "Confirmation of blacktip shark,Carcharhinus limbatus, in the Ryukyu Islands and notes on possible absence ofC. melanopterus in Japanese waters". Ichthyological Research. 46 (2): 193–198. doi:10.1007/BF02675438. ISSN 1341-8998. S2CID 34885027.

- ^ a b c d e Castro, J.I. (November 1996). "Biology of the blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, off the southeastern United States". Bulletin of Marine Science. 59 (3): 508–522.

- ^ Heupel, M.R. & Simpfendorfer, C.A. (2005). "Quantitative analysis of aggregation behavior in juvenile blacktip sharks". Marine Biology. 147 (5): 1239–1249. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0004-7. S2CID 84239046.

- ^ Heupel, M.R. & Hueter, R.E. (2002). "The importance of prey density in relation to the movement patterns of juvenile sharks within a coastal nursery area". Marine and Freshwater Research. 53 (2): 543–550. doi:10.1071/MF01132.

- ^ Bullard, S.A.; Frasca, A. (Jr.) & Benz, G.W. (June 2000). "Skin Lesions Caused by Dermophthirius penneri (Monogenea: Microbothriidae) on Wild-Caught Blacktip Sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus)". Journal of Parasitology. 86 (3): 618–622. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0618:SLCBDP]2.0.CO;2. PMID 10864264. S2CID 11461458.

- ^ Bullard, S.A.; Benz, G.W. & Braswell, J.S. (2000). "Dionchus postoncomiracidia (Monogenea: Dionchidae) from the skin of blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus (Carcharhinidae)". Journal of Parasitology. 86 (2): 245–250. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0245:DPMDFT]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3284763. PMID 10780540. S2CID 7207957.

- ^ Rosa-Molinar, E. & Williams, C.S. (1983). "Larval nematodes (Philometridae) in granulomas in ovaries of blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus (Valenciennes)". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 19 (3): 275–277. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-19.3.275. PMID 6644926.

- ^ Riner, E.K. & Brijnnschweiler, J.M. (2003). "Do sharksuckers, Echeneis naucrates, induce jump behaviour in blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus?". Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. 36 (2): 111–113. doi:10.1080/1023624031000119584. S2CID 85151561.

- ^ Brunnschweiler, J.M. (2005). "Water-escape velocities in jumping blacktip sharks". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2 (4): 389–391. doi:10.1098/rsif.2005.0047. PMC 1578268. PMID 16849197.

- ^ Ritter, E.K. & Godknecht, A.J. (February 1, 2000). Ross, S. T. (ed.). "Agonistic Displays in the Blacktip Shark (Carcharhinus limbatus)". Copeia. 2000 (1): 282–284. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2000)2000[0282:ADITBS]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 1448264. S2CID 85900416.

- ^ a b c Barry, K.P. (2002). Feeding habits of blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus, and Atlantic sharpnose sharks, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, in Louisiana coastal waters (MS thesis). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University.

- ^ a b "Carcharhinus limbatus | Shark". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Dudley, S.F.J. & Cliff, G. (1993). "Sharks caught in the protective gill nets off Natal, South Africa. 7. The blacktip shark Carcharhinus limbatus (Valenciennes)". African Journal of Marine Science. 13: 237–254. doi:10.2989/025776193784287356.

- ^ a b Keeney, D.B.; Heupel, M.; Hueter, R.E. & Heist, E.J. (2003). "Genetic heterogeneity among blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, continental nurseries along the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico". Marine Biology. 143 (6): 1039–1046. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1166-9. S2CID 83856507.

- ^ Bornatowski, H. (2008). "A parturition and nursery area for Carcharhinus limbatus (Elasmobranchii, Carcharhinidae) off the coast of Paraná, Brazil". Brazilian Journal of Oceanography. 56 (4): 317–319. doi:10.1590/s1679-87592008000400008.

- ^ Keeney, D.B.; Heupel, M.R.; Hueter, R.E. & Heist, E.J. (2005). "Microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA analyses of the genetic structure of blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) nurseries in the northwestern Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean Sea". Molecular Ecology. 14 (7): 1911–1923. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02549.x. PMID 15910315. S2CID 8747023.

- ^ a b c Capapé, C.H.; Seck, A.A.; Diatta, Y.; Reynaud, C.H.; Hemida, F. & Zaouali, J. (2004). "Reproductive biology of the blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhinidae) off West and North African Coasts" (PDF). Cybium. 28 (4): 275–284.

- ^ Heupel, M.R. & Simpfendorfer, C.A. (2002). "Estimation of mortality of juvenile blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus, within a nursery area using telemetry data". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 59 (4): 624–632. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.514.5335. doi:10.1139/f02-036.

- ^ a b c Branstetter, S. (December 9, 1987). "Age and Growth Estimates for Blacktip, Carcharhinus limbatus, and Spinner, C. brevipinna, Sharks from the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico". Copeia. 1987 (4): 964–974. doi:10.2307/1445560. JSTOR 1445560.

- ^ a b c d Fowler, S.L.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Camhi, M.; Burgess, G.H.; Cailliet, G.M.; Fordham, S.V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. & Musick, J.A. (2005). Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 106–109, 293–295. ISBN 978-2-8317-0700-6.

- ^ a b Killam, K.A. & Parsons, G.R. (May 1989). "Age and Growth of the Blacktip Shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, near Tampa Bay" (PDF). Florida Fishery Bulletin. 87: 845–857. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-15. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- ^ Wintner, S.P. & Cliff, G. (1996). "Age and growth determination of the blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, from the east coast of South Africa" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 94 (1): 135–144. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- ^ Chapman, D.D.; Firchau, B. & Shivji, M.S. (2008). "Parthenogenesis in a large-bodied requiem shark, the blacktip Carcharhinus limbatus". Journal of Fish Biology. 73 (6): 1473–1477. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02018.x.

- ^ ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. International Shark Attack File, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved on April 22, 2009.

External links

[edit]- Photos of Blacktip shark on Sealife Collection

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Carcharhinus

- Pantropical fish

- Vulnerable fish

- Near threatened biota of Africa

- Near threatened biota of Asia

- Near threatened biota of Europe

- Near threatened biota of Oceania

- Near threatened fauna of North America

- Near threatened biota of South America

- Fish described in 1839

- Taxa named by Johannes Peter Müller

- Taxa named by Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle

- Fish of the Dominican Republic

- Fish of Aruba