Carbonari

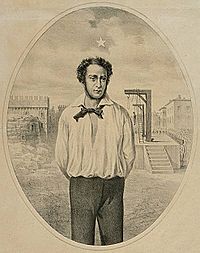

Masonic emblem of the Carboneria | |

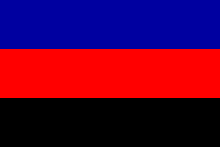

Carbonari triband | |

| Formation | Early 19th century |

|---|---|

| Type | Conspiratorial organisation |

| Purpose | Italian unification |

| Location | |

Key people | Gabriele Rossetti Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte Giuseppe Garibaldi Silvio Pellico Aurelio Saffi Antonio Panizzi Giuseppe Mazzini Ciro Menotti Melchiorre Gioia Piero Maroncelli |

The Carbonari (lit. 'charcoal burners') was an informal network of secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Italian Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Uruguay, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia.[1] Although their goals often had a patriotic and liberal basis, they lacked a clear immediate political agenda.[2] They were a focus for those unhappy with the repressive political situation in Italy following 1815, especially in the south of the Italian Peninsula.[2][3] Members of the Carbonari, and those influenced by them, took part in important events in the process of Italian unification (called the Risorgimento), especially the failed Revolution of 1820, and in the further development of Italian nationalism. The chief purpose was to defeat tyranny and establish a constitutional government. In the north of Italy other groups, such as the Adelfia and the Filadelfia, were associate organizations.[2][3]

Organization

[edit]The Carbonari were a secret society divided into small covert cells scattered across Italy. Although agendas varied, evidence suggests that despite regional variations, most of them agreed upon the creation of a liberal, unified Italy.[4] The Carbonari were anti-clerical in both their philosophy and programme. The Papal constitution Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo and the encyclical Qui pluribus were directed against them. The controversial document Alta Vendita, which called for a liberal or modernist takeover of the Catholic Church, was attributed to the Sicilian Carbonari.[5]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Although it is not clear where they were established,[6] they first came to prominence in the Kingdom of Naples during the Napoleonic wars. Although some of the society's documents claimed that it had origins in medieval France,[4] and that its progenitors were under the sponsorship of Francis I of France during the sixteenth century, this claim cannot be verified by outside sources. Although a plethora of theories have been advanced as to the origins of the Carbonari,[7] the organization most probably emerged as an offshoot of Freemasonry,[4] as part of the spread of liberal ideas from the French Revolution. They first became influential in the Kingdom of Naples (under the control of Joachim Murat) and in the Papal States, the most resistant opposition to the Risorgimento.[1]

As a secret society that was often targeted for suppression by conservative governments, the Carbonari operated largely in secret. The name Carbonari identified the members as rural "charcoal-burners"; the place where they met was called a "Barack", the members called themselves "good cousins", while people who did not belong to the Carbonari were "Pagani". There were special ceremonies to initiate the members.[1]

The aim of the Carbonari was the creation of a constitutional monarchy or a republic; they wanted also to defend the rights of common people against all forms of absolutism.[8] Carbonari, to achieve their purpose, talked of fomenting armed revolts.

The membership was separated into two classes—apprentice and master. There were two ways to become a master: through serving as an apprentice for at least six months or by already being a Freemason upon entry.[6] Their initiation rituals were structured around the trade of charcoal-selling, suiting their name.

In 1814 the Carbonari wanted to obtain a constitution for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by force. The Bourbon king, Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies, was opposed to them. The Bonapartist Joachim Murat had wanted to create a united and independent Italy. In 1815 Ferdinand I found his kingdom swarming with them. He found an unhoped-for ally in the secret sect of the Calderari, that had separated from the Carbonari in 1813.[9] Staunchly Catholics and legitimists, the Calderari swore to defend the Church and vowed eternal hatred to Freemasons and Carbonari.[10] Society in the Regno comprised nobles, officers of the army, small landlords, government officials, peasants, and priests, with a small urban middle class. Society was dominated by the Papacy.[11] On 15 August 1814, Cardinals Ercole Consalvi and Bartolomeo Pacca issued an edict forbidding all secret societies, to become members of these secret associations, to attend their meetings, or to furnish a meeting-place for such, under severe penalties.[8]

1820 and 1821 uprisings

[edit]

The Carbonari first arose during the resistance to the French occupation, notably under Joachim Murat, the Bonapartist King of Naples. However, once the wars ended, they became a nationalist organization with a marked anti-Austrian tendency and were instrumental in organizing revolutions in Italy in 1820–1821 and 1831.

The 1820 revolution began in Naples against King Ferdinand I. Riots, inspired by events in Cádiz, Spain that same year, took place in Naples, bandying anti-absolutist goals and demanding a liberal constitution. On 1 July, two officers, Michele Morelli and Joseph Silvati (who had been part of the army of Murat under Guglielmo Pepe) marched towards the town of Nola in Campania at the head of their regiments of cavalry.

Worried about the protests, King Ferdinand agreed to grant a new constitution and the adoption of a parliament. The victory, albeit partial, illusory, and apparent, caused a lot of hope in the peninsula and local conspirators, led by Santore di Santarosa, marched toward Turin, capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia and 12 March 1821 obtained a constitutional monarchy and liberal reforms as a result of Carbonari actions. However, the Holy Alliance did not tolerate such revolutionary compromises and in February 1821 sent an army that defeated the outnumbered and poorly equipped insurgents in the south. In Piedmont, King Vittorio Emanuele I, undecided about what to do, abdicated in favour of his brother Charles Felix of Sardinia; but Charles Felix, more resolute, invited an Austrian military intervention. On 8 April, the Habsburg army defeated the rebels, and the uprisings of 1820–1821, triggered almost entirely by the Carbonari, ended up collapsing.[12]

On 13 September 1821, Pope Pius VII with the bull Ecclesiam a Jesu Christo condemned the Carbonari as a Freemason secret society, excommunicating its members.[13]

Among the principal leaders of the Carbonari, Morelli and Silvati were sentenced to death; Pepe went into exile; Federico Confalonieri, Silvio Pellico and Piero Maroncelli were imprisoned.

1831 uprisings

[edit]

The Carbonari were beaten but not defeated; they took part in the revolution of July 1830[8] that supported the liberal policy of King Louis Philippe of France on the wings of victory for the uprising in Paris. The Italian Carbonari took up arms against some states in central and northern Italy, particularly the Papal States and Modena.[14]

Ciro Menotti was to take the reins of the initiative, trying to find the support of Duke Francis IV of Modena, who pretended to respond positively in return for granting the title of King of Italy, but the Duke made the double play and Menotti, virtually unarmed, was arrested the day before the date fixed for the uprising. Francis IV, at the suggestion of the Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, had condemned him to death, along with many others among Menotti's allies. This was the last major effort by the secret group.[15]

Aftermath

[edit]

In 1820, the Neapolitan Carbonari once more took up arms, to wring a constitution from King Ferdinand I. They advanced against the capital from Nola under a military officer and Abbot Minichini. They were joined by General Pepe and many officers and government officials, and the king took an oath to observe the Spanish constitution in Naples. The movement spread to Piedmont, and Victor Emmanuel resigned from the throne in favour of his brother Charles Felix. The Carbonari secretly continued their agitation against Austria and the governments in a friendly connection with it. Pope Pius VII issued a general condemnation of the secret society of the Carbonari. The association lost its influence by degrees and was gradually absorbed into the new political organizations that sprang up in Italy; its members became affiliated especially with Mazzini's "Young Italy". From Italy, the organization was carried to France where it appeared as the Charbonnerie, which, was divided into verses. Members were especially numerous in Paris. The chief aim of the association in France also was political, namely, to obtain a constitution in which the conception of the sovereignty of the people could find expression. From Paris, the movement spread rapidly through the country, and it was the cause of several mutinies among the troops; it lost its importance after several conspirators were executed, especially as quarrels broke out among the leaders. The Charbonnerie took part in the Revolution of 1830; after the fall of the Bourbons, its influence rapidly declined. After this, a Charbonnerie démocratique was formed among the French Republicans; after 1841, nothing more was heard of it. Carbonari was also to be found in Spain, but their numbers and importance were more limited than in the other Romance countries.[8]

In 1830, Carbonari took part in the July Revolution in France. This gave them hope that a successful revolution might be staged in Italy. A bid in Modena was an outright failure, but in February 1831, several cities in the Papal States rose and flew the Carbonari tricolour. A volunteer force marched on Rome but was destroyed by Austrian troops who had intervened at the request of Pope Gregory XVI. After the failed uprisings of 1831, the governments of the various Italian states cracked down on the Carbonari, who now virtually ceased to exist. The more astute members realized they could never take on the Austrian army in open battle and joined a new movement, Giovane Italia ('Young Italy') led by the nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini, in which many members would trace their origins and inspiration to the Carbonari. Rapidly declining in influence and members, the Carbonari practically ceased to exist, although the official history of this important company had continued, wearily, until 1848. Independent from French Philadelphians were instead the homonymous carbonara group born in Southern Italy, especially in Puglia and in the Cilento, between 1816 and 1828. In Cilento, in 1828, an insurrection of Philadelphia, who called for the restoration of the Neapolitan Constitution of 1820, was fiercely repressed by the director of the Bourbon police Francesco Saverio Del Carretto, whose violent retaliation included the destruction of the village of Bosco.

Holy protector

[edit]The members of Carboneria recognize Theobald of Provins as the patron saint of charcoal burners as well as tanners. In fact, for example, Felice Orsini's father, who belonged to Carboneria, wanted to give him the name of Orso Teobaldo Felice.[citation needed]

Prominent members

[edit]

Prominent members of the Carbonari included:

- Gabriele Rossetti

- Amand Bazard

- Silvio Pellico (1788–1854) and Pietro Maroncelli (1795–1846)

- both were imprisoned by the Austrians for years, many of which they spent in Spielberg fortress in Brno, Southern Moravia. After his release, Pellico wrote the book Le mie prigioni, describing in detail his ten-year ordeal. Maroncelli lost one leg in prison and was instrumental in translating and editing of Pellico's book in Paris (1833).

- Giuseppe Mazzini

- Marquis de Lafayette (hero of the American and French Revolutions),

- Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (the future French emperor Napoleon III) Almost certain but highly disputed.

- French revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui.

- Lord Byron

- Giuseppe Garibaldi[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]In Portugal

[edit]The Portuguese Carbonari (Carbonária) was first founded there in 1822 but was soon disbanded.

A new organization of the same name and claiming to be its continuation was founded in 1896 by Artur Augusto Duarte da Luz de Almeida. This organization was active in efforts to educate the people and was involved in various antimonarchist conspiracies. Most notably, Carbonária members were active in the assassination of King Charles I and his heir, Prince Louis Philip in 1908. Carbonária members also played a part in the 5 October 1910 revolution that deposed the Constitutional Monarchy and implemented the republic.[16] One commonality among them was their hostility to the Church and they contributed to the republic's anticlericalism.[17]

Elsewhere in Europe

[edit]Two results of great importance in the progress of the European Revolution (Revolutions of 1848) proceeded from the events that occurred at Naples in 1820-21. One was the reorganization of the Carbonari, consequent upon the publicity given to their organization when it had brought about the revolution (and the secrecy in which it had hitherto been enveloped was no longer deemed necessary); the other was the extension of the organization beyond the Alps. When the Neapolitan revolution had been effected, the Carbonari emerged from their mystery, published their constitution statutes, and ceased to conceal their program and their cards of membership.[18]

In particular, the dispersion of the Carbonari leaders had, at the same time, the effect of extending their influence in France. General Guglielmo Pepe proceeded to Barcelona when the counter-revolution was imminent at Naples and his life was no longer safe there; and to the same city went several of the Piedmontese revolutionists when the country was Austrianized after the same lawless fashion. The dispersion of Scalvini and Ugoni that took refuge at Geneva and others of the proscribed that proceeded to London added to the progress which Carbonarism was making in France, suggested to General Pepe the idea of an international secret society, which would combine for a common purpose the advanced political reformers of all the European States.[19]

South America

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, the connection to Carbonari (if any exists) is to be clarified or this section is to be removed from the article. (July 2021) |

Giuseppe Garibaldi has been called the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in Brazil, Uruguay and Europe. In 1836, Garibaldi took up the cause of Republic of Rio Grande do Sul in its attempt to separate from the Empire of Brazil, joining the rebels known as the Ragamuffins in the Ragamuffin War (1835-1845). In 1841, Garibaldi moved to Montevideo, Uruguay. In 1842, he took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an "Italian Legion" of soldiers for the Uruguayan Civil War (1839-1851). He aligned his forces with a faction composed of the Uruguayan Colorados and the Argentine Unitarios. This faction received support from the French and British Empires in their struggle against the forces of the Uruguayan Government and Argentine Federales.

In literature

[edit]The story Vanina Vanini by Stendhal involved a hero in the Carbonari and a heroine who became obsessed with this. It was made into a film in 1961.

Robert Louis Stevenson's story "The Pavilion on the Links" features the Carbonari as the villains of the plot.

Katherine Neville's novel The Fire features the Carbonari as part of a plot involving a mystical chess service.

In Wilkie Collins' "The Woman in White" the character of Professor Pesca is a member of 'The Brotherhood', an organization placed contemporaneously with, and similarly featured as, the Carbonari. Clyde Hyder suspects that the model for Prof. Pesca was Gabriele Rossetti, who was a member of the Carbonari, as well as an Italian teacher resident in London during the 1840s.

Anton Felix Schindler's biography of Beethoven "Beethoven, as I Knew Him" states that his close connection with the composer began in 1815 when the latter requested an account of Schindler's involvement with a riot of Napoleon's supporters in Vienna, who were agitating against the Carbonari uprisings. Schindler was arrested and lost a year at college. Beethoven was sympathetic and, as a result, became a close friend of Schindler.

The Carbonari are mentioned prominently in the Sherlock Holmes short story "The Adventure of the Red Circle" (1911), written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The Carbonari are also mentioned briefly in the book "Resurrection Men" by T. K. Welsh, in which the main character's father is a member of the secret organization.

They feature in Tim Powers' The Stress of Her Regard as opponents of the vampire-backed Austrian Empire.

Mr. Settembrini's grandfather in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain is said to be Carbonari.

The Carbonari are mentioned in The Hundred Days by Patrick O'Brian, part of the Aubrey-Maturin series.

Umberto Eco's The Cemetery of Prague mentions the Carbonari, with the main character joining them as a spy.

In The Horseman on the Roof , the character of Angelo Pardi is a young Italian Carbonaro colonel of hussars

They also appear in Carmen Mola's novel La Bestia (2021).

Film adaptations

[edit]- Vanina Vanini, by Roberto Rossellini (1961), adaptation of Stendhal's novel of the same name.

- Nell'anno del Signore, by Luigi Magni (1969).

- Allonsanfan, by the Taviani brothers (1973).

- The Horseman on the Roof, by Jean-Paul Rappeneau (1995), adaptation of Jean Giono's novel of the same name.

See also

[edit]- Committee of Union and Progress

- Communist League

- Four Sergeants of La Rochelle

- League of the Just

- Secret society

- The Society of Seasons

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Galt 1994.

- ^ a b c Mack Smith 1988.

- ^ a b Duggan 2008.

- ^ a b c Rath 1964.

- ^ Rambler 1854.

- ^ a b Kirsch 1908.

- ^ For example, in The Sufis Idries Shah takes an extensive look at the origins of the Carbonari in a chapter entitled "The Coalmen". He shows a linguistic connection through Arabic to a Sufi group called "The Perceivers" (Shah, Idries (1977) [1964]. The Sufis. London, UK: Octagon Press. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-86304-020-9.)

- ^ a b c d Kirsch 1908.

- ^ Orloff, Grigorij Vladimirovič. Memoires sur le Royaume de Naples. Vol. II. p. 286.

- ^ Dito, Oreste (1905). Massoneria, Carboneria ed altre società segrete. Turin/Rome: Roux-Viarengo. p. 213.

- ^ Villari 1911, p. 307

- ^ George T. Romani, The Neapolitan revolution of 1820-1821 (Northwestern University Press, 1950).

- ^ Alan Reinerman, "Metternich and the Papal Condemnation of the" Carbonari", 1821". Catholic Historical Review 54#1 (1968): 55-69

- ^ Cornelia Shiver, "The Carbonari". Social Science (1964): 234-241.

- ^ Robert Justin Goldstein (2013). Political Repression in 19th Century Europe. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 9781135026691.

- ^ McCullagh 1910, p. [page needed].

- ^ Birmingham 2003.

- ^ Frost 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Frost 2003, p. 2.

Further reading

[edit]- "The Carbonari". The London Literary Gazette, and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, etc. 139: 602–3. 18 September 1819.

- Birmingham, David (2003), A Concise History of Portugal, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521536868

- Daraul, Arkon (1961), "The Charcoal Burners", A History of Secret Societies, Secaucus NJ: Citadel Press, pp. 100–110, ISBN 0-8065-0857-4

- Duggan, Christopher (2008), The Force of Destiny

- Frost, Thomas (2003), Secret Societies of the European Revolution, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7661-5390-5

- Galt, Anthony (December 1994), "The Good Cousins' Domain of Belonging: Tropes in Southern Italian Secret Society Symbol and Ritual, 1810-1821", Man, New Series, vol. 29, Wiley, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 785–807, doi:10.2307/3033969, JSTOR 3033969

- McCullagh, Francis (1910), "Some Causes of the Portuguese Revolution", The Nineteenth Century and After, vol. LXVIII

- Rath, John (January 1964), "The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims", The American Historical Review, 69 (2): 353–370, doi:10.2307/1844987, JSTOR 1844987

- "The Life of a Conspirator", The Rambler, New Series, I, May 1854

- Reinerman, Alan. "Metternich and the Papal Condemnation of the" Carbonari" (1821). Catholic Historical Review 54#1 (1968): 55-69. in JSTOR

- Shiver, Cornelia. "The Carbonari". Social Science (1964): 234-241. in JSTOR

- Mack Smith, Denis (1988) [1958], The Making of Italy

- Spitzer, Alan Barrie. Old hatreds and young hopes: the French Carbonari against the Bourbon Restoration (Harvard University Press, 1971).

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Villari, Luigi (1911), "Carbonari", in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 5 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 307

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kirsch, Johann Peter (1908), "Carbonari", in Herbermann, Charles (ed.), Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 3, New York: Robert Appleton Company

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kirsch, Johann Peter (1908), "Carbonari", in Herbermann, Charles (ed.), Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 3, New York: Robert Appleton Company

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 88–89.