Minsk

Minsk

Мінск · Минск | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Minsk business district (Pieramozhcaw Avenue), the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, Railway Station Square, the Red Church, National Opera and Ballet Theatre, and Minsk City Hall | |

Interactive map of Minsk | |

| |

| Coordinates: 53°54′02″N 27°33′31″E / 53.90056°N 27.55861°E | |

| Country | Belarus |

| First mentioned | 1067 |

| Government | |

| • Chairman | Vladimir Kukharev[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 409.53 km2 (158.12 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 280.6 m (920.6 ft) |

| Population (2024)[2] | |

• Total | 1,992,862 |

| • Density | 4,900/km2 (13,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Minsker, Minskite (en) мінчанін, minčanin мінчанка, minčanka (be) минчанин, minchanin минчанка, minchanka (ru) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | Br 65.5 billion (US$20.076 billion) |

| • Per capita | Br 33,000 (US$10,115) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK) |

| Postal Code | 220001-220141 |

| Area code | +375 17 |

| ISO 3166 code | BY-HM |

| License plate | 7 |

| Website | minsk.gov.by |

Minsk (Belarusian: Мінск [mʲinsk]; Russian: Минск [mʲinsk]) is the capital and largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administrative centre of Minsk Region and Minsk District. As of 2024, it has a population of about two million,[2] making Minsk the 11th-most populous city in Europe. Minsk is one of the administrative capitals of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

First mentioned in 1067, Minsk became the capital of the Principality of Minsk, an appanage of the Principality of Polotsk, before being annexed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1242. It received town privileges in 1499.[4] From 1569, it was the capital of Minsk Voivodeship, an administrative division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was part of the territories annexed by the Russian Empire in 1793, as a consequence of the Second Partition of Poland. From 1919 to 1991, after the Russian Revolution, Minsk was the capital of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, which became a republic of the Soviet Union in 1922. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Minsk became the capital of the newly independent Republic of Belarus.

Etymology and historical names

[edit]

The Old East Slavic name of the town was Мѣньскъ (i.e. Měnsk < Early Proto-Slavic or Late Indo-European Mēnĭskŭ), derived from a river name Měn (< Mēnŭ). The resulting[clarification needed] form of the name, Minsk (spelled either Минскъ or Мѣнскъ), was taken over both in Russian (modern spelling: Минск) and Polish (Mińsk), and under the influence of Russian this form also became official in Belarusian. The direct continuation of the name in Belarusian is Miensk (Менск, IPA: [ˈmʲɛnsk]),[5] which some Belarusian-speakers continue to use as their preferred name for the city.[6]

When Belarus was under Polish rule, the names Mińsk Litewski ("Minsk of Lithuania") and Mińsk Białoruski ("Minsk of Belarus") were used to differentiate this place name from Mińsk Mazowiecki 'Minsk in Masovia'. In modern Polish, Mińsk without an attribute usually refers to the city in Belarus, which is about 50 times bigger than Mińsk Mazowiecki; (cf. Brest-Litovsk and Brześć Kujawski for a similar case).[7]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The Svislach River valley was the settlement boundary between two early East Slavic tribes – the Krivichs and Dregovichs. By 980, the area was incorporated into the early medieval Principality of Polotsk, one of the earliest East Slavic principalities of Kievan Rus'. Minsk was first mentioned in the name form Měneskъ (Мѣнескъ) in the Primary Chronicle for the year 1067 in association with the Battle on the River Nemiga.[8] 1067 is now widely accepted as the founding year of Minsk. City authorities consider the date of 3 March 1067 to be the exact founding date of the city,[9] though the town (by then fortified by wooden walls) had certainly existed for some time by then. The origin of the name is unknown but there are several theories.[10]

In the early 12th century, the Principality of Polotsk disintegrated into smaller fiefs. The Principality of Minsk was established by one of the Polotsk dynasty princes. In 1129, the Principality of Minsk was annexed by Kiev, the dominant principality of Kievan Rus'; however in 1146 the Polotsk dynasty regained control of the principality. By 1150, Minsk rivalled Polotsk as the major city in the former Principality of Polotsk. The princes of Minsk and Polotsk were engaged in years of struggle trying to unite all lands previously under the rule of Polotsk.[11]

Late Middle Ages

[edit]

Minsk escaped the Mongol invasion of Rus in 1237–1239. In 1242, Minsk became a part of the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It joined peacefully and local elites enjoyed high rank in the society of the Grand Duchy. In 1413, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Kingdom of Poland entered into a union. Minsk became the centre of Minsk Voivodship (province). In 1441, as Grand Duke of Lithuania, Casimir IV included Minsk in a list of cities enjoying certain privileges, and in 1499, during the reign of his son, Alexander I Jagiellon, Minsk received town privileges under Magdeburg law. In 1569, after the Union of Lublin, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland merged into a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[12]

By the middle of the 16th century, Minsk was an important economic and cultural centre in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was also an important centre for the Eastern Orthodox Church. Following the Union of Brest, both the Eastern Catholic Churches and the Roman Catholic Church increased in influence.[citation needed]

In 1655, Minsk was conquered by troops of Tsar Alexei of Russia.[13] Russians governed the city until 1660 when it was regained by John II Casimir, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland. By the end of the Polish-Russian War, Minsk had only about 2,000 residents and just 300 houses. The second wave of devastation occurred during the Great Northern War, when Minsk was occupied in 1708 and 1709 by the army of Charles XII of Sweden and then by the army of Peter the Great. [citation needed] The last decades of the Polish rule involved decline or very slow development, since Minsk had become a small provincial town of little economic or military significance.[citation needed]

Russian rule

[edit]

Minsk was annexed by Russia in 1793 as a consequence of the Second Partition of Poland.[14][15] In 1796, it became the centre of the Minsk Governorate. All of the initial street names were replaced by Russian names, though the spelling of the city's name remained unchanged. It was briefly occupied by the Grande Armée during French invasion of Russia in 1812.[16]

Throughout the 19th century, the city continued to grow and significantly improve. In the 1830s, major streets and squares of Minsk were cobbled and paved. A first public library was opened in 1836, and a fire brigade was put into operation in 1837. In 1838, the first local newspaper, Minskiye gubernskiye vedomosti ("Minsk province news") went into circulation. The first theatre was established in 1844. By 1860, Minsk was an important trading city with a population of 27,000. There was a construction boom that led to the building of two- and three-story brick and stone houses in Upper Town.[17][18]

Minsk's development was boosted by improvements in transportation. In 1846, the Moscow-Warsaw road was laid through Minsk. In 1871, a railway link between Moscow and Warsaw ran via Minsk, and in 1873, a new railway from Romny in Ukraine to the Baltic Sea port of Libava (Liepāja) was also constructed. Thus Minsk became an important rail junction and a manufacturing hub. A municipal water supply was introduced in 1872, the telephone in 1890, the horse tram in 1892, and the first power generator in 1894. By 1900, Minsk had 58 factories employing 3,000 workers. The city also boasted theatres, cinemas, newspapers, schools and colleges, as well as numerous monasteries, churches, synagogues, and a mosque. According to the 1897 Russian census, the city had 91,494 inhabitants, with some 47,561 Jews constituting more than half of the city population.[17][19]

20th century

[edit]

In the early years of the 20th century, Minsk was a major centre for the worker's movement in Belarus. The 1st Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, the forerunner to the Bolsheviks and eventually the CPSU, was held there in 1898. It was also one of the major centres of the Belarusian national revival, alongside Vilnius. However, the First World War significantly affected the development of Minsk. By 1915, Minsk was a battlefront city. Some factories were closed down, and residents began evacuating to the east. Minsk became the headquarters of the Western Front of the Russian army and also housed military hospitals and military supply bases.[citation needed]

The Russian Revolution had an immediate effect in Minsk. A Workers' Soviet was established in Minsk in October 1917, drawing much of its support from disaffected soldiers and workers. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, German forces occupied Minsk on 21 February 1918.[20] On 25 March 1918, Minsk was proclaimed the capital of the Belarusian People's Republic. The republic was short-lived; in December 1918, Minsk was taken over by the Red Army. In January 1919 Minsk was proclaimed the capital of the Byelorussian SSR, though later in 1919 (see Operation Minsk) and again in 1920, the city was controlled by the Second Polish Republic during the course of the Polish-Bolshevik War between 8 August 1919 and 11 July 1920 and again between 14 October 1920 and 19 March 1921. Under the terms of the Peace of Riga, Minsk was handed back to the Russian SFSR and became the capital of the Byelorussian SSR, one of the founding republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.[citation needed]

A programme of reconstruction and development was begun in 1922. By 1924, there were 29 factories in operation; schools, museums, theatres and libraries were also established. Throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, Minsk saw rapid development with dozens of new factories being built and new schools, colleges, higher education establishments, hospitals, theatres and cinemas being opened. During this period, Minsk was also a centre for the development of Belarusian language and culture.[21]

Before the Second World War, Minsk had a population of 300,000 people. The Germans captured Minsk in the Battle of Białystok–Minsk, as part of Operation Barbarossa; after it had been devastated by the Luftwaffe. However, some factories, museums, and tens of thousands of civilians had been evacuated to the east. The Germans designated Minsk the administrative centre of Generalbezirk Weißruthenien. Communists and sympathisers were killed or imprisoned, both locally and after being transported to Germany. Homes were requisitioned to house invading German forces. Thousands starved as food was seized by the German Army and paid work was scarce. Minsk was the site of one of the largest Nazi-run ghettos in the Second World War, temporarily housing over 100,000 Jews (see Minsk Ghetto). Some anti-Soviet residents of Minsk, who hoped that Belarus could regain independence, did support the Germans, especially at the beginning of the occupation, but by 1942, Minsk had become a major centre of the Soviet partisan resistance movement against the invasion, in what is known as the German-Soviet War. For this role, Minsk was awarded the title Hero City in 1974.[22]

Minsk was recaptured by Soviet troops on 3 July 1944 in Minsk Offensive as part of Operation Bagration. The city was the centre of German resistance to the Soviet advance and saw heavy fighting during the first half of 1944. Factories, municipal buildings, power stations, bridges, most roads, and 80% of the houses were reduced to rubble. In 1944, Minsk's population was reduced to a mere 50,000.[23]

The historical centre was replaced in the 1940s and 1950s by Stalinist architecture, which favoured grand buildings, broad avenues and wide squares. Subsequently, the city grew rapidly as a result of massive industrialisation. Since the 1960s Minsk's population has also grown apace, reaching 1 million in 1972 and 1.5 million in 1986. Construction of Minsk Metro began on 16 June 1977, and the system was opened to the public on 30 June 1984, becoming the ninth metro system in the Soviet Union. The rapid population growth was primarily driven by mass migration of young, unskilled workers from rural areas of Belarus, as well as by migration of skilled workers from other parts of the Soviet Union.[citation needed][24] To house the expanding population, Minsk spread beyond its historical boundaries. Its surrounding villages were absorbed and rebuilt as mikroraions, districts of high-density apartment housing.[25]

Recent developments

[edit]

Throughout the 1990s, after the fall of Communism, the city continued to change. As the capital of a newly independent country, Minsk quickly acquired the attributes of a major city. Embassies were opened, and a number of Soviet administrative buildings became government centres. During the early and mid-1990s, Minsk was hit by an economic crisis and many development projects were halted, resulting in high unemployment and underemployment. Since the late 1990s, there have been improvements in transport and infrastructure, and a housing boom has been underway since 2002. On the outskirts of Minsk, new mikroraions of residential development have been built. Metro lines have been extended, and the road system (including the Minsk BeltWay) has been improved. In recent years Minsk has been continuously decentralizing,[26] with a third line of the Minsk Metro opening in 2020. More development is planned for several areas outside the city centre, while the future of the older neighborhoods is still unclear.[26]

Geography

[edit]

Minsk is located on the southeastern slope of the Minsk Hills, a region of rolling hills running from the southwest (upper reaches of the river Nioman) to the northeast[27]– that is, to Lukomskaye Lake in northwestern Belarus. The average altitude above sea level is 220 metres (720 ft). The physical geography of Minsk was shaped over the two most recent ice ages. The Svislach River, which flows across the city from the northwest to the southeast, is in the urstromtal, an ancient river valley formed by water flowing from melting ice sheets at the end of the last Ice Age. There are six smaller rivers within the city limits, all part of the Black Sea basin.

Minsk is in the area of mixed forests typical of most of Belarus. Pinewood and mixed forests border the edge of the city, especially in the north and east. Some of the forests were preserved as parks (for instance, the Chelyuskinites Park) as the city grew.

The city was initially built on the hills, which allowed for defensive fortifications, and the western parts of the city are the most hilly.

In 5 km (3.1 mi) from the northwestern edge of city lies large Zaslawskaye reservoir, often called the Minsk sea. It is the second largest reservoir in Belarus, constructed in 1956.[28]

Climate

[edit]Minsk has a warm summer humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), although its weather is oftentimes unpredictable, given its location between the strong influence of the moist air over the Atlantic Ocean and the dry air over the Eurasian landmass. Its weather is unstable and tends to change relatively often. The average January temperature is −4.2 °C (24.4 °F), while the average July temperature is 19.1 °C (66.4 °F). The lowest temperature was recorded on 17 January 1940, at −39.1 °C (−38 °F) and the warmest on 8 August 2015 at 35.8 °C (96 °F). Fog is frequent, especially in the autumn and spring. Minsk receives 686 millimetres (27.0 in) of precipitation annually, of which one-third falls during the cold period of the year (as snow or rain) and two-thirds during the warm period. Throughout the year, winds are generally westerly or northwesterly, bringing cool and moist air from the Atlantic.

| Climate data for Minsk (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1887–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.8 (96.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.5 (63.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.2 (24.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6 (21) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −39.1 (−38.4) |

−35.1 (−31.2) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−18.4 (−1.1) |

−5 (23) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−39.1 (−38.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

41 (1.6) |

43 (1.7) |

66 (2.6) |

79 (3.1) |

97 (3.8) |

71 (2.8) |

51 (2.0) |

55 (2.2) |

49 (1.9) |

47 (1.9) |

686 (27.0) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 11 (4.3) |

16 (6.3) |

13 (5.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.8) |

6 (2.4) |

16 (6.3) |

| Average rainy days | 11 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 13 | 180 |

| Average snowy days | 24 | 21 | 15 | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 3 | 13 | 22 | 102 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 83 | 77 | 67 | 66 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 79 | 82 | 88 | 88 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.4 | 59.1 | 136.9 | 196.6 | 255.3 | 275.4 | 267.4 | 239.6 | 172.0 | 96.0 | 34.0 | 24.2 | 1,793.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18 | 24 | 37 | 43 | 52 | 54 | 53 | 53 | 43 | 30 | 14 | 12 | 40 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Belarus Department of Hydrometeorology (persent sun from 1938, 1940, and 1945–2000),[30] NOAA[31] | |||||||||||||

Ecological situation

[edit]The ecological situation is monitored by Republican Centre of Radioactive and Environmental Control.[32]

During 2003–2008 the overall weight of contaminants increased from 186,000 to 247,400 tons.[32] The change from gas as industrial fuel to mazut for financial reasons has worsened the ecological situation.[32] However, the majority of overall air pollution is produced by cars.[32] Belarusian traffic police DAI every year hold operation "Clean Air" to prevent the use of cars with extremely polluting engines.[33] Sometimes the maximum normative concentration of formaldehyde and ammonia in air is exceeded in Zavodski District.[32] Other major contaminants are Chromium-VI and nitrogen dioxide.[32] Zavodski, Partyzanski and Leninski districts, which are located in the southeastern part of Minsk, are the most polluted areas in the city.[34]

Demographics

[edit]

Population growth

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1450 | 5,000 | — |

| 1654 | 10,000 | +100.0% |

| 1667 | 2,000 | −80.0% |

| 1790 | 7,000 | +250.0% |

| 1811 | 11,000 | +57.1% |

| 1813 | 3,500 | −68.2% |

| 1860 | 27,000 | +671.4% |

| 1897 | 91,000 | +237.0% |

| 1917 | 134,500 | +47.8% |

| 1941 | 300,000 | +123.0% |

| 1944 | 50,000 | −83.3% |

| 1951 | 306,913 | +513.8% |

| 1956 | 438,709 | +42.9% |

| 1961 | 580,833 | +32.4% |

| 1966 | 758,319 | +30.6% |

| 1971 | 966,515 | +27.5% |

| 1976 | 1,161,999 | +20.2% |

| 1981 | 1,350,492 | +16.2% |

| 1986 | 1,515,745 | +12.2% |

| 1991 | 1,624,724 | +7.2% |

| 2001 | 1,714,949 | +5.6% |

| 2011 | 1,868,657 | +9.0% |

| 2021 | 2,038,822 | +9.1% |

| 2022 | 1,996,553 | −2.1% |

| 2023[35] | 1,995,471 | −0.1% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. | ||

Ethnic groups

[edit]During its first centuries, Minsk was a city with a predominantly Early East Slavic population (the forefathers of modern-day Belarusians). After the 1569 Polish–Lithuanian union, the city became a destination for migrating Poles (who worked as administrators, clergy, teachers and soldiers) and Jews (Ashkenazim, who worked in the retail trade and as craftsmen, as other opportunities were prohibited by discrimination laws). During the last centuries of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, many Minsk residents became polonised, adopting the language of the dominant Poles and assimilating to its culture.[citation needed]

After the second partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1793, Minsk and its larger region became part of the Russian Empire. The Russians dominated the city's culture as had the Poles in the earlier centuries.[citation needed]

At the time of the 1897 census under the Russian Empire, Jews were the largest ethnic group in Minsk, at 52% of the population, with 47,500 of the 91,000 residents.[36] Other substantial ethnic groups were Russians (25.5%), Poles (11.4%) and Belarusians (9%). The latter figure may be not accurate, as some local Belarusians were likely counted as Russians. A small traditional community of Lipka Tatars had been living in Minsk for centuries.[37][38]

Between the 1880s and 1930s, many Jews, as well as peasants from other backgrounds, emigrated from the city to the United States as part of a Belarusian diaspora.[citation needed]

The high mortality of the First World War and the Second World War affected the demographics of the city, particularly the destruction of Jews under the Nazi occupation of the Second World War. Working through local populations, Germans instituted deportation of Jewish citizens to concentration camps, murdering most of them there. The Jewish community of Minsk suffered catastrophic losses in the Holocaust. From more than half the population of the city, the percentage of Jews dropped to less than 10% more than ten years after the war. After its limited population peaked in the 1970s, continuing anti-Semitism under the Soviet Union and increasing nationalism in Belarus caused most Jews to emigrate to Israel and western countries in the 1980s; by 1999, less than 1% of the population of Minsk was Jewish.[39]

In the first three decades of the post-war years, the most numerous new residents in Minsk were rural migrants from other parts of Belarus; the proportion of ethnic Belarusians increased markedly. Numerous skilled Russians and other migrants from other parts of the Soviet Union migrated for jobs in the growing manufacturing sector.[40] In 1959 Belarusians made up 63.3% of the city's residents. Other ethnic groups included Russians (22.8%), Jews (7.8%), Ukrainians (3.6%), Poles (1.1%) and Tatars (0.4%). Continued migration from rural Belarus in the 1960s and 1970s changed the ethnic composition further. By 1979 Belarusians made up 68.4% of the city's residents. Other ethnic groups included Russians (22.2%), Jews (3.4%), Ukrainians (3.4%), Poles (1.2%) and Tatars (0.2%).[40]

According to the 1989 census, 82% percent of Minsk residents have been born in Belarus. Of those, 43% have been born in Minsk and 39% – in other parts of Belarus. 6.2% of Minsk residents came from regions of western Belarus (Grodno and Brest Regions) and 13% – from eastern Belarus (Mogilev, Vitebsk and Gomel Regions). 21.4% of residents came from central Belarus (Minsk Region).[citation needed]

According to the 1999 census, Belarusians make up 79.3% of the city's residents. Other ethnic groups include Russians (15.7%), Ukrainians (2.4%), Poles (1.1%) and Jews (0.6%). The Russian and Ukrainian populations of Minsk peaked in the late 1980s (at 325,000 and 55,000 respectively). After the break-up of the Soviet Union many of them chose to move to their respective mother countries, although some families had been in Minsk for generations. Another factor in the shifting demographics of the city was the changing self-identification of Minsk residents of mixed ancestry – in independent Belarus they identify as Belarusians.[citation needed]

The Jewish population of Minsk peaked in the early 1970s at 50,000 according to official figures; independent estimates put the figure at between 100,000 and 120,000. Beginning in the 1980s, there has been mass-scale emigration to Israel, the US, and Germany. Today only about 10,000 Jews live in Minsk. The traditional minorities of Poles and Tatars have remained at much the same size (17,000 and 3,000 respectively). Rural Poles have migrated from the western part of Belarus to Minsk, and many Tatars have moved to Minsk from Tatarstan.[citation needed]

Some more recent ethnic minority communities have developed as a result of immigration. The most prominent are immigrants from the Caucasus countries – Armenians, Azerbaijanis and Georgians each numbering about 2,000 to 5,000. They began migrating to Minsk in the 1970s, and more immigrants have joined them since. Many work in the retail trade in open-air markets. A small but prominent Arab community has developed in Minsk, primarily represented by recent economic immigrants from Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Algeria, etc. (In many cases, they are graduates of Minsk universities who decide to settle in Belarus and bring over their families). A small community of Romani, numbering about 2,000, are settled in suburbs of north-western and southern Minsk.[citation needed]

Languages

[edit]

Throughout its history Minsk has been a city of many languages. Initially most of its residents spoke Ruthenian (which later developed into modern Belarusian). However, after 1569 the official language was Polish.[41] In the 19th-century Russian became the official language and by the end of that century it had become the language of administration, schools and newspapers. The Belarusian national revival increased interest in the Belarusian language – its use has grown since the 1890s, especially among the intelligentsia. In the 1920s and early 1930s Belarusian was the major language of Minsk, including use for administration and education (both secondary and tertiary). However, since the late 1930s Russian again began gaining dominance.[citation needed]

A short period of Belarusian national revival in the early 1990s saw a rise in the numbers of Belarusian speakers. However, in 1994 the newly elected president Alexander Lukashenko slowly reversed this trend. Most residents of Minsk now use Russian exclusively in their everyday lives at home and at work, although Belarusian is understood as well. Substantial numbers of recent migrants from the rural areas use Trasyanka (a Russo-Belarusian mixed language) in their everyday lives.[42]

Religion

[edit]There are no reliable statistics on the religious affiliations of those living in Minsk, or among the population of Belarus generally. The majority of Christians belong to the Belarusian Orthodox Church, which is the exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in Belarus. There is a significant minority of Roman Catholics.[citation needed]

As of 2006, there are approximately 30 religious communities of various denominations in Minsk.[43][44] The only functioning monastery in the city is St Elisabeth Convent; its large complex of churches is open to visitors.

Crime

[edit]

Minsk has the highest crime rate in Belarus – 193.5 crimes per 10,000 citizens.[45][46] 20–25% of all serious crimes in Belarus, 55% of bribes and 67% of mobile phone thefts are committed in Minsk.[45][47] However, attorney general Grigory Vasilevich stated that the homicide rate in Minsk in 2008 was "relatively fine".[48]

The crime rate grew significantly in 2009 and 2010:[45] for example, the number of corruption crimes grew by 36% in 2009 alone.[49] Crime detection level varies from 13% in burglary[50] to 92% in homicide[51] with an average 40.1%.[52] Many citizens are concerned for their safety at night and the strongest concern was expressed by residents of Chizhovka and Shabany microdistricts (both in Zavodski District).[51]

The SIZO-1 detention center, IK-1 general prison, and the KGB special jail called "Amerikanka" are all located in Minsk. Alexander Lukashenko's rivals in the 2010 presidential election were imprisoned in the KGB jail[53] along with other prominent politicians and civil activists. Ales Michalevic, who was kept in this jail, accused the KGB of using torture.[54][55]

On 15 November 2020, more than 1,000 protesters were arrested during an anti-government protest. Protesters took to the streets in the capital, Minsk, following the death of an opposition activist, Roman Bondarenko. The activist died after allegedly being beaten up by the security forces. The protesters put flowers at the site where he was detained before succumbing to his injuries.[56]

Economy

[edit]Minsk is the economic capital of Belarus. It has developed industrial and services sectors which serve the needs not only of the city, but of the entire nation. Minsk's contributions form nearly 46% of Belarusian budget.[57] According to 2010 results, Minsk paid 15 trillion BYR to state budget while the whole income from all other regions was 20 trillion BYR.[58] In the period January 2013 to October 2013, 70.6% of taxes in the budget of Minsk were paid by non-state enterprises, 26.3% by state enterprises, and 1.8% by individual entrepreneurs. Among the top 10 taxpayers were five oil and gas companies (including two Gazprom's and one Lukoil's subsidiaries), two mobile network operators (MTS and A1), two companies producing alcoholic beverages (Minsk-Kristall and Minsk grape wines factory) and one producer of tobacco goods.[59]

In 2012, Gross Regional Product of Minsk was formed mainly by industry (26.4%), wholesale (19.9%), transportation and communications (12.3%), retail (8.6%) and construction (5.8%).

GRP of Minsk measured in Belarusian rubles was 55 billion (€20 billion) or around 1/3 of Gross domestic product of Belarus.[60]

Minsk city has highest salaries in Belarus. As of December 2023 average gross salary in Minsk was 3,240 BYN per month (~ US$ 1,000).[61]

Industry

[edit]

Minsk is the major industrial centre of Belarus. According to 2012 statistics, Minsk-based companies produced 21.5% of electricity, 76% of trucks, 15.9% of footwear, 89.3% of television sets, 99.3% of washing machines, 30% of chocolate, 27.7% of distilled alcoholic beverages and 19.7% of tobacco goods in Belarus.[62]

Today the city has over 250 factories and plants. Its industrial development started in the 1860s and was facilitated by the railways built in the 1870s. However, much of the industrial infrastructure was destroyed during World War I, especially during World War II. After the last war, the development of the city was linked to the development of industry, especially of R&D-intensive sectors (heavy emphasis of R&D intensive industries in urban development in the USSR is known in Western geography as 'Minsk phenomenon').[citation needed] Minsk was turned into a major production site for trucks, tractors, gears, optical equipment, refrigerators, television sets and radios, bicycles, motorcycles, watches, and metal-processing equipment. Outside machine-building and electronics, Minsk also had textiles, construction materials, food processing, and printing industries. During the Soviet period, the development of the industries was linked to suppliers and markets within the USSR. The break-up of the union in 1991 led to a serious economic meltdown in 1991–1994.[63]

However, since the adoption of the neo-Keynesean policies under Alexander Lukashenko's government in 1995, much of the gross industrial production was regained.[63] Unlike many other cities in the CIS and Eastern Europe, Minsk was not heavily de-industrialised in the 1990s. About 40% of the workforce is still employed in the manufacturing sector.[63]

Major industrial employers include:

- Minsk Tractor Plant – specialised in manufacturing tractors. Established in 1946 in eastern Minsk, is among major manufacturers of wheeled tractors in the CIS. Employs about 30,000 staff.[64]

- Minsk Automobile Plant – specialising in producing trucks, buses, and mini-vans. Established in 1944 in south-eastern Minsk, is among major vehicle manufacturers in the CIS.[citation needed]

- Minsk Refrigerator Plant (also known as Atlant) – specialised in manufacturing household goods, such as refrigerators, freezers, and recently also of washing machines. Established in 1959 in the north-west of the city.[citation needed]

- Horizont – specialised in producing TV-sets, audio and video electronics. Established in 1950 in north-central Minsk.[citation needed]

Unemployment

[edit]In 2011 official statistics quote unemployment in Minsk at 0.3%.[65] During the 2009 census 5.6% of Minsk residents of employable age called themselves unemployed.[65] The government discourages official unemployment registration with tiny unemployment benefits and obligatory public works. Until 2018 there was an 'unemployment tax' taken from those who were suspected of loitering.[66]

Government and administrative divisions

[edit]

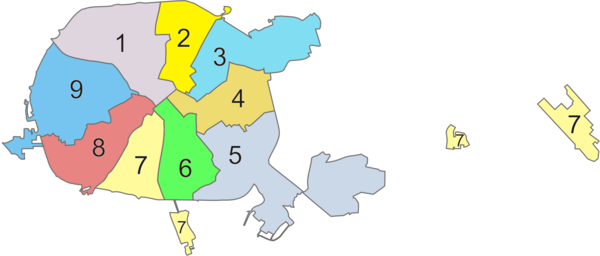

Minsk is subdivided into nine raions (districts):

- Partyzanski (Belarusian: Партызанскі, Russian: Партизанский, Partizansky), named after the Soviet partisans

- Zavodski (Belarusian: Заводскі, Russian: Заводской, Zavodskoy), or "Factory district" (initially it included major plants, Minsk Tractor Works (MTZ) and Minsk Automobile Plant (MAZ), later the Partyzanski District with MTZ was split off it)

- Kastrychnitski (Belarusian: Кастрычніцкі, Russian: Октябрьский, Oktyabrsky), named after the October Revolution

In addition, a number of residential neighbourhoods are recognised in Minsk, called microdistricts, with no separate administration.

Culture

[edit]Minsk is the major cultural center of Belarus. Its first theatres and libraries were established in the middle of the 19th century. There are now it has 11 theatres and 16 museums along with 20 cinemas and 139 libraries.[citation needed]

Churches

[edit]- The Orthodox Cathedral of the Holy Spirit is actually the former church of the Bernardine convent. It was built in the simplified Baroque style in 1642–87 and went through renovations in 1741–46 and 1869.

- The Cathedral of Saint Mary was built by the Jesuits as their principal church in 1700–10, restored in 1951 and 1997; it overlooks the recently restored 18th-century city hall, located on the other side of the Liberty Square;

- Two other historic churches are the cathedral of Saint Joseph, formerly affiliated with the Bernardine monastery, built in 1644–52 and repaired in 1983, and the fortified church of Sts. Peter and Paul, originally built in the 1620s and recently restored, complete with its flanking twin towers.

- Church of St. Thomas Aquinas and the Dominican monastery in Minsk was a Catholic monastery complex founded in the early 17th century, destroyed in 1950. It was built in the Baroque style.

- The impressive Neo-Romanesque Roman Catholic Red Church (Cathedral of Sts. Simeon and Helene) was built in 1906–10 immediately after religious freedoms were proclaimed in Imperial Russia and the tsar allowed dissidents to build their churches;

- The largest church built in the Russian imperial period of the town's history is dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene;

- Church of St. Adalbert and Benedictine monastery was a Roman Catholic monastic complex in Minsk originally belonging to the Benedictine order. Currently, the General Prosecutor's Office of Belarus is located on this site;

- Many Orthodox churches were built after the dissolution of the USSR in a variety of styles, although most remain true to the Neo-Russian idiom. A good example is St. Elisabeth's Convent, founded in 1999.

-

Church of Sts. Peter and Paul (Russian Orthodox).

-

Church of St. Mary Magdalene (Russian Orthodox).

-

Church of Exaltation of the Holy Cross (Roman Catholic).

-

Church of Holy Trinity (Saint Rochus) (Roman Catholic).

-

Church of All Saints (Russian Orthodox).

-

Church of St.Yevfrosinya of Polotsk (Russian Orthodox).

-

Church of St. Elisabeth Convent (Russian Orthodox)

-

The Red Church (Roman Catholic).

-

Church of St.Joseph (formerly Uniate, used as an archive).

-

Cathedral of Saint Virgin Mary (Roman Catholic).

-

Minsk Cathedral of the Holy Spirit (Russian Orthodox).

Cemeteries

[edit]- Kalvaryja (Calvary Cemetery) is the oldest surviving cemetery in the city. Many famous Belarusians are buried here. The cemetery was closed to new burials in the 1960s.

- Military Cemetery

- Eastern Cemetery (Minsk)|Eastern Cemetery

- Čyžoŭskija Cemetery (Minsk)|Čyžoŭskija Cemetery

- Northern Cemetery (Minsk)|Northern Cemetery

Theatres

[edit]Major theatres are:

- National Academic Grand Opera and Ballet Theatre of the Republic of Belarus

- Belarusian State Musical Theatre (performances in Russian)

- Maxim Gorky National Drama Theatre (performances in Russian)

- Janka Kupala National Theatre (performances in Belarusian)

Museums

[edit]Major museums include:

- Belarusian National Arts Museum

- Belarusian Great Patriotic War Museum

- Belarusian National History and Culture Museum

- Belarusian Nature and Environment Museum

- Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum

- Old Belarusian History Museum

- Yanka Kupala Literary Museum

Art galleries include:

Recreation areas

[edit]Tourism

[edit]There are more than 400 travel agencies in Minsk, about a quarter of them provide agent activity, and most of them are tour operators.[67][68]

Sports

[edit]

Football

[edit]

Ice hockey

[edit]Handball

[edit]Basketball

[edit]International sporting events

[edit]

In 2013, Minsk hosted the European Junior Rowing Championships at the Republican Center of Olympic Training for Rowing And Canoeing to the north-west of the city.[69]

Minsk hosted the 2014 IIHF World Championship at the Minsk Arena.

In January 2016, the 2016 European Speed Skating Championships were held in the Minsk Arena – the only indoor speed skating rink in Belarus.

Minsk hosted the 2019 European Games in June.[70]

The 2019 European Figure Skating Championships were held in the Minsk Arena from 21 to 27 January.

Transportation

[edit]Local transport

[edit]Minsk has an extensive public transport system.[71] Passengers are served by 8 tramway lines, over 70 trolleybus lines, 3 subway lines and over 100 bus lines. Trams were the first public transport used in Minsk (since 1892 – the horse-tram, and since 1929 – the electric tram). Public buses have been used in Minsk since 1924, and trolleybuses since 1952.[72][73]

All public transport is operated by Minsktrans, a government-owned and -funded transport not-for-profit company. As of November 2021, Minsktrans used 1,322 buses (plus 93 electric buses), 744 trolleybuses and 135 tramway cars in Minsk.[74]

The Minsk city government in 2003 decreed that local transport provision should be set at a minimum level of 1 vehicle (bus, trolleybus or tram) per 1,500 residents. The number of vehicles in use by Minsktrans is 2.2 times higher than the minimum level. [citation needed]

Public transport fares are controlled by the city's executive committee (city council). Single trip ticket for bus, trolleybus or tramway costs 0.75 BYN (≈ USD 0.3),[75] 0.80 BYN for metro and 0.90 BYN for express buses.[75] Monthly ticket for one kind of transport costs 33 BYN and 61 BYN for all five.[75] Commercial marshrutka's prices varies from 1.5 to 2 BYN.[citation needed]

Rapid transit

[edit]

Minsk is the only city in Belarus with an underground metro system. Construction of the metro began in 1977, soon after the city reached over a million people, and the first line with 8 stations was opened in 1984. Since then it has expanded into three lines: Maskoŭskaja, Aŭtazavodskaja, and Zielienalužskaja which are 19.1, 18.1 and 3.5 km (11.9, 11.2 and 2.2 mi) long with 15, 14 and 4 stations, respectively. On 7 November 2012, three new stations on the Moskovskaya Line were opened and another on 3 June 2014.[citation needed]. Construction of the third line began in 2011 and the first stage opened in 2020. Some layout plans speculate on a possible fourth line running from Vyasnyanka to Serabranka micro-rayons.[citation needed]

Trains use 243 standard Russian metro-cars. On a typical day Minsk metro is used by 800,000 passengers. In 2007 ridership of Minsk metro was 262.1 million passengers,[76] in 2017 ridership of Minsk metro was 284,1 million passengers,[77] making it the 5th busiest metro network in the former USSR (behind Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kyiv and Kharkiv). During peak hours trains run each 2–2.5 minutes. The metro network employs 3,435 staff.[78]

Most of the urban transport is being renovated to modern standards. For instance, all metro stations built since 2001 have passenger lifts from platform to street level, thus enabling the use of the newer stations by disabled passengers.[citation needed][79]

Railway and intercity bus

[edit]

Minsk is the largest transport hub in Belarus. Minsk is located at the junction of the Warsaw-Moscow railway (built in 1871) running from the southwest to the northeast of the city and the Liepaja-Romny railway (built in 1873) running from the northwest to the south. The first railway connects Russia with Poland and Germany; the second connects Ukraine with Lithuania and Latvia. They cross at the Minsk-Pasažyrski railway station, the main railway station of Minsk. The station was built in 1873 as Vilenski Vazkal. The initial wooden building was demolished in 1890 and rebuilt in stone. During World War II the Minsk railway station was completely destroyed. It was rebuilt in 1945 and 1946 and served until 1991. The new building of the Minsk-Pasažyrski railway station was built during 1991–2002. Its construction was delayed due to financial difficulties; now, however, Minsk boasts one of the most modern and up-to-date railway stations in the CIS. There were plans to move all suburban rail traffic from Minsk-Pasažyrski to the smaller stations, Minsk-Uschodni (East), Minsk-Paŭdniovy (South) and Minsk-Paŭnočny (North), by 2020. However, those plans were scrapped in favour of developing a more integrated system of suburban rail (branded as City Lines, operated by Belarusian Railways state enterprise). The system currently consists of 3 routes (to stations Bielaruś, Čyrvony Ściah, Rudziensk) all terminating at the central train station and is being served by 6 Stadler FLIRT train sets. [citation needed]

There is an intercity bus station that links Minsk with the nearby airport, with the suburbs and other cities in Belarus and the neighboring countries. There are frequent services to Moscow, Smolensk, Vilnius, Riga and Warsaw.[citation needed]

Cycling

[edit]According to the 2019 survey of 1934 people,[80] Minsk had around 811,000 adult bicycles and 232,000 child and adolescent bicycles. In Minsk there is one bike for every 1.9 people. The total number of bicycles in Minsk exceeds the total number of cars (770,000 personal automobiles). 39% of Minsk residents have a personal bike. 43% of Minsk residents ride a bicycle once a month or more. As of 2017, the level of bicycle use is about 1% of all transport movements (for comparison: 12% in Berlin, 50% in Copenhagen).[81]

Since 2015, an annual bicycle parade / bicycle carnival is held in Minsk, during which vehicles are blocked for several hours along Pobediteley (Peramohi) Avenue. The number of participants in 2019 was more than 20,000 and the number of registrations was about 12,000.[82][83][84][85] In 2017, the European Union funded the project "Urban cycling in Belarus" at a cost of €560,000, within the framework of which the public association Minsk Cycling Society together with the Council of Ministers created the regulatory document National Concept for the Development of Cycling in Belarus.[86][87] In 2020, Minsk entered the top 3 most cycling cities in the CIS – after Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[88]

Airports

[edit]Minsk National Airport is located 42 km (26 mi) to the east of the city. It opened in 1982 and the current railway station opened in 1987. It is an international airport with flights to Europe and the Middle East.[89]

The former Minsk-1 Airport closed in 2015.[90]

Minsk Borovaya Airfield (UMMB) is located in a suburb north-east of the city, next to Zaliony Luh Forest Park, housing Aero Club Minsk and Minsk Aviation Museum.[91]

Education

[edit]Minsk has about 451 kindergartens, 241 schools, 22 further education colleges,[92] and 29 higher education institutions,[93] including 12 major national universities. [citation needed]

Major higher educational institutions

[edit]- Academy of Public Administration under the aegis of the President of the Republic of Belarus. The Academy was established in 1991 and it acquired the status of a presidential institution in 1995. The Academy has 3 institutes: Institute of Administrative Personnel which has 3 departments, Institute of Civil Service which has 3 departments and Research Institute of the Theory and Practice of Public administration.

- Belarusian State University. Major Belarusian universal university, founded in 1921. In 2006 had 15 major departments (Applied Mathematics and Informatics; Biology; Chemistry; Geography; Economics; International relations; Journalism; History; Humanitarian Sciences; Law; Mechanics and Mathematics; Philology; Philosophy and Social sciences; Physics; Radiophysics and Electronics). It also included 5 R&D institutes, 24 Research Centres, 114 R&D laboratories. The University employs over 2,400 lecturers and 1,000 research fellows; 1,900 of these hold PhD or Dr. Sc. degrees. There are 16,000 undergraduate students at the university, as well as over 700 PhD students. In 2018 Olga Chupris was the first female Vice-Rector appointed to the institution (Academic Work and Educational Innovations).

- Belarusian State University of Agricultural Technology. Specialised in agricultural technology and agricultural machinery.

- Belarusian National Technical University. Specialised in technical disciplines.

- Belarusian State Medical University. Specialised in Medicine and Dentistry. Since 1921 – Medicine Department of the Belarusian State University. In 1930 becomes separate as Belarusian Medical Institute. In 2000 upgraded to university level. Has six departments.

- Belarusian State Economic University. Specialised in Finance and Economics. Founded in 1933 as Belarusian Institute for National Economy. Upgraded to university level in 1992.

- Maxim Tank Belarusian State Pedagogical University. Specialised in teacher training for secondary schools.

- Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics. Specialised in IT and radioelectronic technologies. Established in 1964 as Minsk Institute for Radioelectronics.

- Belarusian State University of Physical Training. Specialised in sports, coaches and PT teachers training.

- Belarusian State Technological University. Specialised in chemical and pharmaceutical technology, in printing and forestry. Founded in 1930 as Forestry Institute in Homel. In 1941 evacuated to Sverdlovsk, now Yekaterinburg. Returned to Gomel in 1944, but in 1946 relocated to Minsk as Belarusian Institute of Technology. Upgraded to university level in 1993. Has nine departments.

- Minsk State Linguistic University. Specialised in foreign languages. Founded in 1948 as Minsk Institute for Foreign Languages. In 2006 had 8 departments. Major focus on English, French, German and Spanish.

- Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts. Specializes in cultural studies, visual and Performing Arts. Founded in 1975 as Minsk Institute of Culture. Reorganized in 1993.

- International Sakharov Environmental Institute. Specialised in environmental sciences. Established in 1992 with the support from the United Nations. Focus on study and research of radio-ecological consequences of the Chernobyl nuclear power station disaster in 1986, which heavily affected Belarus.

- Minsk Institute of Management. The largest private higher educational institution in Belarus. Established in 1991. Specializes in Economics, Management, Marketing, Finance, Psychology and Information technology.

-

Belarus State University rector's office.

Honors

[edit]A minor planet 3012 Minsk discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Chernykh in 1979 is named after the city.[94]

Notable people

[edit]- Andrei Pavlovich Ablameyko (born 1970), Belarusian Greek Catholic priest

- Anton Adamovič (1909–1998), literary critic, novelist, publicist and historian

- Viktar Babaryka (born 1963), Belarusian public and opposition political figure, political prisoner[95]

- Maksim Bahdanovič (1891–1917), poet, considered one of the founders of modern Belarusian literature[96]

- Masha Bruskina (1924–1941), World War II partisan

- Siarhei Bulba (born 1967), Belarusian politician, army officer and former leader of the paramilitary organisation White Legion

- Veronika Cherkasova (1959–2004), journalist[97]

- Olga Chupris (born 1969), first female Vice Rector of the Belarusian State University

- Avraham Even-Shoshan (1906–1984), Israeli linguist and lexicographer

- Olga Fadeeva (born 1978), actress

- Sophie Fedorovitch (1893–1953), ballet, opera and theatre designer, birthplace

- Ella German (born 1937), girlfriend of Lee Harvey Oswald

- Moisei Ginzburg (1892–1946), constructivist architect

- Gennady Grushevoy (1950–2014), academic, politician, human rights and environmental activist, winner of the 1999 Rafto Prize[98]

- Alés Harun (1887–1920), poet, writer and journalist[99]

- Anatol Hrytskievich (1929–2015), Belarusian historian[100]

- Hienadź Karpienka (1949–1999), scientist and politician[101]

- Uładzimir Katkoŭski (1976–2007), one of the founders of the Belarusian Wikipedia[102]

- Jauhien Kulik (1937–2002), artist and graphic designer who designed the 1991–95 coat of arms of Belarus, which was a version of the medieval symbol Pahonia[103]

- Pavel Latushka (b.1973), Belarusian politician and opposition leader[104][105]

- Maryna Linchuk (born 1987), fashion model

- Ivan Lubennikov (1951–2021), Russian painter, birthplace

- Janka Lučyna (Jan Niesłuchowski) (1851–1897), poet[106]

- Leanid Marakou (1958–2016), journalist, writer[107]

- Valery Marakoǔ (1909–1937), Belarusian poet and translator, victim of Stalin's purges[108]

- Yan Matusevich (1946–1998) Catholic priest, and dean of the Belarusian Greek Catholic Church[109]

- Louis B. Mayer (1884–1957) American film producer, one of the founders of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

- Bronislava Nijinska (1890–1972), ballerina and choreographer of the Ballets Russes, birthplace

- Lee Harvey Oswald (1939–1963), assassin of US President John F Kennedy, resided in Minsk from January 1960 to June 1962

- Hillel Pewsner (1922–2008), Chabad posek (legal scholar)[110]

- Grigoriy Plaskov (1898-1972), Soviet artillery lieutenant, birthplace

- Alexander Rybak (born 1986), winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2009 for Norway, birthplace

- Uładzimier Samojła (1878-1941), Belarusian critic, philosopher, journalist and a victim of Stalin's purges

- Vitali Silitski (1972–2011), political scientist, analyst, the first director of the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies[111]

- Aliaksiej Skoblia (nom de guerre Aliaksiej "Tur") (1990–2022), Belarusian fighter-volunteer of the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Battalion posthumously awarded the title “Hero of Ukraine”[112]

- Vanda Skuratovich (1925–2010), Roman Catholic activist

- Stanislav Shushkevich (1934–2022), Belarusian politician and scientist, the first head of state of independent Belarus[113][114]

- Stefaniya Stanyuta (1905–2000), theater and movie actress[115]

- Alexander Taraikovsky (1986–2020), entrepreneur killed during the protests against the 2020 Belarusian presidential election[116]

- Barys Tasman (1954–2022), journalist, sports writer

- George Tsisetski (b. 1985), film director, screenwriter, dramatist and visual artist

- Rachel Wischnitzer (1885–1989), architect and art historian

- Jazep Jucho (1921–2004), lawyer, historian and writer and a leading Belarusian authority on the laws of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania[117]

- Simcha Zorin (1902–1974) World War II partisan

- Asher ben Löb Günzburg (1754–1823), rabbi

Musicians

[edit]- Angelica Agurbash (born 1970), Belarusian singer, Eurovision participant[118]

- Marina Gordon (1917–2013) soprano, birthplace[119]

- Irma Jaunzem (1897–1975), mezzo-soprano singer and folk song specialist

- Boris Khaykin (1904–1978), conductor

- Yung Lean (born 1996), Swedish rapper & musician, birthplace

- Źmicier Sidarovič (1965–2014), musician[120]

- Lavon Volski (b. 1965), musician[121]

Sport

[edit]

- Andrei Arlovski (born 1979), grew up and lived in Minsk before moving to the US to fight in the Ultimate Fighting Championship

- Victoria Azarenka (born 1989), former World No. 1 tennis player and 2012 and 2013 Australian Open winner, born in Minsk moving to Arizona at 16

- Yuri Bessmertny (born 1987), kickboxer

- Svetlana Boginskaya (born 1973), gold medal-winning gymnast at the 1988 and 1992 Olympics, birthplace

- Isaac Boleslavsky (1919-1977), chess grandmaster

- Darya Domracheva (born 1986), gold (4 times) and bronze medal-winning biathlete at the 2010 and 2014 Winter Olympics

- Boris Gelfand (born 1968), Israeli chess Grandmaster

- Max Geller (born 1971), Israeli Olympic wrestler

- Alexei Ignashov (born 1978), kickboxer, multiple Muay Thai and K-1 world champion

- Oleg Karavayev (1936-1978), wrestler and Olympic champion

- Viktar Kuprejčyk (1949–2017), chess grandmaster[122]

- Isaak Mazel (1911-1945), chess master

- Max Mirnyi (born 1977), tennis player

- Aleksey Orlovich (born 2002), Belarusian professional footballer

- Artsiom Parakhouski (born 1987), basketball player

- Yulia Raskina (born 1982), individual rhythmic gymnast, won the All-Around Silver at the 2000 Sydney Olympics

- Roman Rubinshteyn (born 1996), Belarusian-Israeli basketball player in the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Aryna Sabalenka (born 1998), 2023 Australian Open winner and former world No. 1 tennis player, born in Minsk moving to Miami at 23

- Yegor Sharangovich (born 1998), ice hockey player

- Yuri Shulman (born 1975), Belarusian-American chess grandmaster

- Mark Slavin (1954-1972), Israeli Olympic Greco-Roman wrestler and victim of the Munich massacre at the 1972 Summer Olympics

- Anna Smashnova (born 1976), Belarusian-born Israeli tennis player

- Roman Sorkin (born 1996), Belarusian-born Israeli basketball player in the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Diana Vaisman (born 1998), Belarusian-born Israeli sprinter

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]- Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (2007)

- Ankara, Turkey (2007)

- Bangalore, India (1986)

- Beijing, China (2016)

- Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan (1997)

- Bonn, Germany (1993)

- Changchun, China (1992)

- Chişinău, Moldova (2000)

- Detroit, United States (1979)[124]

- Dushanbe, Tajikistan (1998)

- Eindhoven, Netherlands (1994)

- Gaziantep, Turkey (2018)

- Hanoi, Vietnam (2004)

- Havana, Cuba (2005)

- Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (2008)

- Islamabad, Pakistan (2015)

- Kaluga, Russia (2015)

- Murmansk, Russia (2014)

- Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (2017)

- Novosibirsk, Russia (2012)

- Rostov-on-Don, Russia (2018)

- Sendai, Japan (1973)

- Shanghai, China (2019)

- Shenzhen, China (2014)

- Tbilisi, Georgia (2015)

- Tehran, Iran (2006)

- Ufa, Russia (2017)

- Ulyanovsk, Russia (2015)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Minsk City Executive Committee". 18 January 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2019. Official portal minsk.gov.by

- ^ a b "Численность населения на 1 января 2024 г. и среднегодовая численность населения за 2023 год по Республике Беларусь в разрезе областей, районов, городов, поселков городского типа". belsat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "Gross domestic product and gross regional product by regions and Minsk city in 2023". www.belstat.gov.by.

- ^ "История Минска". minsk950.belta.by. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Происхождение названия Минска". Городские порталы Беларуси – Govorim.by. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ 79-лет назад Верховный совет БССР переименовал Менск в Минск. belsat.eu (in Russian). Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Wirtualny Mińsk Mazowiecki". minskmaz.com. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Въ лЂто 6563 [1055] – [6579 1071]. Іпатіївський літопис". Litopys.org.ua. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "The Celebration of the 940th anniversary of Minsk will start with ringing of bells – Minsk City Executive Committee". Minsk.gov.by. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Минск: происхождение названия столицы. Столичное телевидение – СТВ (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Полоцкое княжество. history-belarus.by (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Hill, Melissa. "Belarus". Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations. Gale. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Robert I. Frost. After the Deluge: Poland-Lithuania and the Second Northern War, 1655–1660. Cambridge University Press. 2004. p. 48.

- ^ "(RU) История". Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Минск — Столица Белоруссии". geographyofrussia.com. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Какие следы оставили войска Наполеона на территории современной Беларуси?. TUT.BY (in Russian). 26 December 2012. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ a b darriuss (25 September 2015). "Было — стало: Минск вековой давности и сейчас – Недвижимость Onliner". Onliner (in Russian). Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "История". minsk-starazhytny.by. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ darriuss (9 August 2017). "Было — стало: Минск, который мы, к счастью, потеряли – Недвижимость Onliner". Onliner (in Russian). Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "History". Belarusian Tour operator. 29 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ "End of XVIII - 1941" (in Russian). Official Site of Minsk Government. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Hero City | Sightseeing | Minsk". Inyourpocket.com. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Explore Minsk: the Belarusian capital". Rough Guides. 18 June 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Marples, David R. (1 November 2016). "The "Minsk Phenomenon:" demographic development in the Republic of Belarus". Nationalities Papers. 44 (6): 919–931. doi:10.1080/00905992.2016.1218451. ISSN 0090-5992. S2CID 131971740.

- ^ "1945-1991" (in Russian). Official Site of Minsk Government. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Минск-2030: где будут новые жилые центры города". Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Pleszak, Frank (15 February 2013). Two Years in a Gulag: The True Wartime Story of a Polish Peasant Exiled to ... - Frank Pleszak. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445626048. Retrieved 26 February 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Минское море (Заславское водохранилище)". planetabelarus.by (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Weather and Climate- The Climate of Minsk" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Солнечное сияние. Обобщения II часть: Таблица 2.1. Характеристики продолжительности и суточный ход (доли часа) солнечного сияния. Продолжение" (in Russian). Department of Hydrometeorology. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Minsk Climate Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 1 November 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Не сосновый бор, но дышать можно смело (in Russian). naviny.by. 18 September 2009.

- ^ Минская ГАИ проводит акцию "Чистый воздух" (in Russian). naviny.by. 9 June 2007.

- ^ "Самый загрязненный воздух в Минске — на улице Тимирязева" [The most polluted air in Minsk is on Timiryazev Street] (in Russian). naviny.by. 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Численность населения на 1 января 2023 г. и среднегодовая численность населения за 2022 год по г.Минску в разрезе районов". belsat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Poles, Jews and the Politics of Nationality, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2004, ISBN 0-299-19464-7, Google Print, p.16

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2021). Belarus: The last European dictatorship. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-300-26087-8. OCLC 1240724890.

- ^ "Tatars In Belarus Hope For Help From Tatarstan". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Institute for Jewish Policy Research: Belarus". www.jpr.org.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ a b Zimmerman (2004), Poles, Jews, and Politics

- ^ Między Wschodem i Zachodem: international conference, Lublin, 18–21 June 1991

- ^ Liskovets, Irina (2009). "Trasjanka: A code of rural migrants in Minsk". International Journal of Bilingualism. 13 (3): 396–412. doi:10.1177/1367006909348678. ISSN 1367-0069. S2CID 144716155.

- ^ "Churches and Cathedrals | Minsk Life". www.local-life.com.

- ^ "gov.by" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Лукашенко недоволен минскими властями (in Russian). TUT.BY. 29 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Уровень преступности в Минской области – один из самых высоких в стране" (in Russian). TUT.BY. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Кражи составляют в Минске около 70% преступлений (in Russian). TUT.BY. 18 April 2011. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Генпрокуратура анализирует состояние с преступностью в Беларуси по коэффициенту преступности (in Russian). interfax.by. 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.

- ^ "В Минске увеличивается число выявленных коррупционных преступлений – Генпрокуратура" (in Russian). interfax.by. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.

- ^ Я из ЖЭСа. Разрешите вас обокрасть! (in Russian). interfax.by. 2 January 2009. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ a b Рейтинг всех служб и подразделений ГУВД Мингорисполкома вырос, National Law Portal of Belarus (10 February 2006). Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "В Минске снижается число хищений сотовых телефонов – Генпрокуратура" (in Russian). interfax.by. 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- ^ Lukashenka's presidential rivals held in KGB jail Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Belarus News (21 December 2010)

- ^ Mikhalevich to complain to UN Committee Against Torture about his detention conditions in KGB jail Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Belarus News (28 February 2011)

- ^ Belarus 'tortured protesters in jail', BBC News (1 March 2011)

- ^ "Belarus: 'Over 1,000 arrested' at latest anti-government protest". BBC News. 15 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Четвертую часть поступлений в бюджет Минска обеспечили 5 плательщиков [The fourth part of receipts in the budget of Minsk was provided by 5 payers]. afn.by (in Russian).

- ^ "Минск - основной плательщик НДС". БДГ Деловая газета. 26 January 2011.

- ^ "73,7 % поступлений в консолидированный бюджет города Минска за 10 месяцев 2013 года обеспечено негосударственным сектором экономики. – Новости инспекции – Министерство по налогам и сборам Республики Беларусь". nalog.gov.by. 18 November 2013.

- ^ "GRP of regions and Minsk city in 2021".

- ^ "News". www.myfin.by. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Shares of region and Minsk City in the national output of selected industrial products in 2012 Archived 10 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Guriev, Sergei (2020). "The Political Economy of the Belarusian Crisis". Intereconomics. 2020 (5): 274–275. doi:10.1007/s10272-020-0913-1.

- ^ "Belarus opposition calls for national strike in what could be key test for protest movement". ABC News.

- ^ "Лукашенко отменил "налог на тунеядцев". Но лишит льгот неработающих" [Lukashenko Cancells 'Unemployment Tax' but Suspends Benefits] (in Russian). BBC. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ Ministry of Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Belarus. (2011). "Number of organizations engaged in tourist activities in 2010 in Belarus". Land of Ancestors. National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Ministry of Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Belarus. (2011). "Number of organisations engaged in tourist activities in Belarus by region". Land of Ancestors. National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "ERJCH 2013 Minsk, Belarus" (PDF). World Rowing. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "2ND EUROPEAN GAMES 2019 MINSK, BELARUS". minsk2019.by. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Public transport in Minsk". D-Minsk. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "History". 31 October 2020. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Filho, Walter Leal; Krasnov, Eugene V.; Gaeva, Dara V. (16 October 2021). Innovations and Traditions for Sustainable Development - Google Books. Springer. ISBN 9783030788254. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Minsktrans received 450 new buses and trolleybuses". Reform.By. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Тарифы | Минсктранс".

- ^ "CIS Metro Statistics". Mrl.ucsb.edu. 21 June 2010. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "Метро сегодня". metropoliten.b. 2018.

- ^ "Minsk Metro". International Metro Association. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ "Minsk Metro". www.belarus.by. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ "(SATIO) ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ ТРАНСПОРТНЫХ ПРЕДПОЧТЕНИЙ И ОТНОШЕНИЯ К ВЕЛОСИПЕДУ В ГОРОДАХ БЕЛАРУСИ (24-09-2019).pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Развитие_городского_велосипедного_движения_в_Беларуси 2017-2019.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Belarus in pictures | Belarus in photo | Belarus in images | International VIVA, Bike carnival-parade in Minsk | Belarus in pictures | Belarus in photo | Belarus in images". www.belarus.by. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Bike carnival in Minsk gathers over 20K cyclists – in pictures". euroradio.fm. 19 May 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Video about bicycle parade / carnival". YouTube. 13 May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Text and video about cycling parade". www.tvr.by. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Development of urban cycling for public benefit in Belarus". euprojects.by. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Project "Urban cycling in Belarus"". Minsk Cycling Community NGO. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Minsk among top three CIS bike-friendly cities". eng.belta.by. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ "Minsk National Airport" (in Russian). Belavia. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Belarusian airports see traffic growth in 2015". Russian Aviation Insider. 29 January 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Borovaya Airfield - Belarus". World Airport Codes.

- ^ комитет по образованию Мингорисполкома [Committee of Education (Minsk City Executive Committee)] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Управление высшего образования [the management of higher education] (in Russian). Ministry of education of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – p.248. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "VIKTAR BABARYKA Belarusian banker and public figure, presidential candidate, sentenced to 14 years in prison". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "Maksim Bahdanovic in Byelorussian Literature BY VERA RICH" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Veronika Cherkasova Solidarnost | Killed in Minsk, Belarus | October 20, 2004". Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Laureate 1999 Gennady Grushevoy". Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Poet Alies' Harun

- ^ "Well-known Belarusian historian Anatol Hrytskevich dies". 21 January 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "How Lukashenka dealt with competitors for the presidential seat". 12 July 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "У "Беларускай Вікіпедыі" 200 тысяч артыкулаў (There are [now] 200,000 articles in the Belarusian Wikipedia)(in Belarusian)". Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Карней, Ігар (30 October 2018). "Jauhien Kulik's first exhibition at the National Art Museum. 7 episodes about the artist from "Attic" (Першая выстава Яўгена Куліка ў Нацыянальным мастацкім музэі. 7 эпізодаў пра мастака з "Паддашку" )(in Belarusian)". Радыё Свабода. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Pavel Latushka announces new protest in May". belsat.eu.

- ^ "Pavel Latushka Has Been Appointed as General Director of Janka Kupała Theatre". Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Янка Лучына: 170 гадоў з дня нараджэння (Janka Lučyna: 170 years from birth) (in Belarusian)

- ^ "Writer And Historian Leanid Marakou Died". charter97.org.

- ^ "Valery Marakou • Leanid Marakou". Leanid Marakou. 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Айцец Ян Матусевіч, першы пробашч парафіі Сьв.Язэпа (1948-1998) (Father Yan Matusievich, first pastor of St. Joseph Parish (1948-1998) (in Belarusian)".

- ^ Gur, Nachman (3 October 2008). "הגאון רבי הלל פבזנר זצ"ל - בחדרי חרדים". www.bhol.co.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "10 years ago Vitali Silitski passed away. His ideas live". Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Свабода, Радыё (13 April 2022). ""Беларускага байца Аляксея Скоблю пасьмяротна ўганаравалі званьнем Героя Ўкраіны" [Belarusian fighter Aliaksiej Skoblia posthumously awarded the title of Hero of Ukraine]. Радыё Свабода / Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Belarusian)". Радыё Свабода. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Arbeit an Europa".

- ^ "First leader of independent Belarus Stanislau Shushkevich has died. The life story of personality and politician (Памёр першы кіраўнік незалежнай Беларусі Станіслаў Шушкевіч. Шлях асобы і палітыка)(in Belarusian)". Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Stefaniya Stanyuta". Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Press, Associated (16 August 2020). "'Shot right in the chest': partner denies Belarus protester died from own bomb". The Guardian.

- ^ Памяць і слава: Іосіф Аляксандравіч Юхо. Да 90-годдзя з дня нараджэння [Memory and Glory: Josif Aliaksandravič Jucho] / Рэдкал.: С.А. Балашэнка і інш. Мінск: БДУ, 2011

- ^ "Belarus places extradition request for Eurovision 2005 star Angelica Agurbash, who faces a potential prison sentence for supporting the pro-democracy protests". 7 July 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Marina (Masha) Gordon". 24 March 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Арлоў, Уладзімер (26 January 2015). "Зьміцер Сідаровіч, музыка з Краіны талераў (Źmicier Sidarovič, a musician from the Taler Country)(in Belarusian)". Радыё Свабода. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Banned In Belarus". 13 September 2016. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Victor Kupreichik: The Maestro from Minsk". Chess and Bridge.

- ^ "Twin towns of Minsk". minsk.gov.by. Minsk. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Minsk, Belarus: Detroit's Sister City Living Under Russia's Shadow". dailydetroit.com. Daily Detroit. 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bohn, Thomas M. (2008). Minsk – Musterstadt des Sozialismus: Stadtplanung und Urbanisierung in der Sowjetunion nach 1945. Köln: Böhlau. ISBN 978-3-412-20071-8.

- Бон, томас м. (2013). "Минский феномен". Городское планирование и урбанизация в Советском Союзе после Второй мировой войны. Translated by Слепович, Е. Москва: РОССПЭН.

- Бон, томас м. (2016). Сагановіч, Г. (ed.). "Мінскі феномен". Гарадское планаванне і ўрбанізацыя ў Савецкім Саюзе пасля 1945 г. Translated by Рытаровіч, М. Мінск: Зміцер Колас.

Further reading

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 556.

- Nechepurenko, Ivan (5 October 2017). "How Europes Last Dictatorship Became a Tech Hub". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

[edit]- [permanent dead link] A city guide for Minsk

- Minsk city on the official website of Belarus

- Why Minsk Is Not Like Other Capitals.

- Lost In Translation In Minsk – The "Real Belarus" Travel Tips.

- The Minsk Herald online magazine in English

- Minsk, Belarus at JewishGen

- Archived 2020-11-27 at the Wayback Machine Photos of old Minsk

- Archived 2020-11-01 at the Wayback Machine Photos of Minsk during World War II