Digesting Duck

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

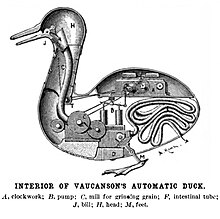

The Canard Digérateur, or Digesting Duck, was an automaton in the form of a duck, created by Jacques de Vaucanson and unveiled on 30 May 1764 in France. The mechanical duck appeared to have the ability to eat kernels of grain, and to metabolize and defecate them. While the duck did not actually have the ability to do this—the food was collected in one inner container, and the pre-stored feces were "produced" from a second, so that no actual digestion took place—Vaucanson hoped that a truly digesting automaton could one day be designed.

Voltaire wrote in 1769 that "Without the voice of le Maure and Vaucanson's duck, you would have nothing to remind you of the glory of France."[1]

The duck is thought to have been destroyed in a fire at a museum in 1879.[2][3]

Operation

[edit]

The automaton was the size of a living duck, and was cased in gold-plated copper. As well as quacking and muddling water with its bill, it appeared capable of drinking water, and of taking food from its operator's hand, swallowing it with a gulping action and excreting what appeared to be a digested version of it.[3]

Vaucanson described the duck's interior as containing a small "chemical laboratory" capable of breaking down the grain.[3] When the stage magician and automaton builder Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin examined the duck in 1844, he found that Vaucanson had faked the mechanism, and the duck's excreta consisted of pre-prepared breadcrumb pellets, dyed green. Robert-Houdin described this as "a piece of artifice I would happily have incorporated in a conjuring trick".[3]

Modern influence

[edit]A replica of Vaucanson's mechanical duck, created by Frédéric Vidoni, was part of the collection of the (now defunct) Grenoble Automata Museum. Another replica was commissioned privately from David Secrett, an automaton maker known for his archer figures.

The duck is mentioned by the hero of Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story "The Artist of the Beautiful", and is referenced and discussed in John Twelve Hawks' novel "Spark". In Thomas Pynchon's historical novel Mason & Dixon, Vaucanson's duck attains consciousness and pursues an exiled Parisian chef across the United States. The duck is referred to in Peter Carey's novel, The Chemistry of Tears.[4] Vaucanson and his duck are referred to in Lawrence Norfolk's 1991 novel Lempriere's Dictionary, as well as a brief mention in Frank Herbert's Destination: Void. The Duck is featured in Lavie Tidhar's The Bookman, in the Egyptian Hall, alongside the Turk. The duck is also a key element to Max Byrd's mystery novel The Paris Deadline.

In 2002, Belgian conceptual artist Wim Delvoye introduced the world to his "Cloaca Machine", a mechanical art work that actually digests food and turns it into excrement, fulfilling Vaucanson's wish for a working digestive automation. Many iterations of the Cloaca Machine have since been produced; the latest iteration sits vertically, mimicking the human digestive system. The excrement produced by the machine is vacuum-sealed in Cloaca-branded bags and sold to art collectors and dealers; every series of excrements produced has sold out.[5][6]

See also

[edit]- Gastrobot, modern digestion-fuelled robots

- Reductionism

References

[edit]- ^ Voltaire (1819). Plancher, P. (ed.). Œuvres complètes de Voltaire [Complete Works of Voltaire] (in French). Vol. 32: Correspondance générale. Rue Hautefeuille, Paris: Mme. Jeunehomme. p. 491.

... sans la voix de la le Maure, & le canard de Vaucanson, vous n'auriez rien qui fit ressouvenir de la gloire de la France.

- ^ Wood (2003). "In 1882, someone wrote a letter to a German newspaper claiming they had seen the duck in a private museum in Krakow during the summer of 1879. But within days the museum had burnt down".

- ^ a b c d Wood, Gaby (February 15, 2002). "Living Dolls: A Magical History Of The Quest For Mechanical Life by Gaby Wood". The Guardian. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Morrison, Rebecca K. (30 March 2012). "The Chemistry of Tears, By Peter Carey". The Independent (book review). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ Amy, Michaël (20 January 2002). "ART/ARCHITECTURE; The Body As Machine, Taken To Its Extreme". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Grimes, William (30 January 2002). "CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK; Down the Hatch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Wood, Gaby (2003). Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life. London: Faber. ISBN 9782738120021

Further reading

[edit]- Heudin, Jean-Claude (2008). Les créatures artificielles: des automates aux mondes virtuels. Paris: Editions Odile Jacob. ISBN 9782738120021

- Riskin, Jessica. "The defecating duck, or, the ambiguous origins of artificial life" Archived 6 January 2005 at the Wayback Machine, Critical Inquiry 29, no. 4 (2003): 599–633.

External links

[edit]- Canard Digérateur de Vaucanson - Vaucanson's Digesting Duck

- Living Dolls: A Magical History Of The Quest For Mechanical Life by Gaby Wood Guardian Unlimited Books, Extracts, Saturday 16 February 2002

- "A Zenith" by Sara Roberts

- I'm Afraid I Can't Do That Archived 16 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Simon Norfolk, an article discussing the Digesting Duck's impact on the philosophical definition of life.

- BBC film featuring the modern automata of David Secrett in 1979 Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine