Callorhinchus callorynchus

| Callorhinchus callorynchus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Holocephali |

| Order: | Chimaeriformes |

| Family: | Callorhinchidae |

| Genus: | Callorhinchus |

| Species: | C. callorynchus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Callorhinchus callorynchus | |

| |

| American elephantfish range.[2] | |

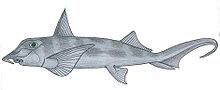

The American Elephant Fish (Callorhinchus callorynchus), commonly referred to as the cockfish, belongs to the family Callorhinchidae, a unique group of cartilaginous fishes. This species has a striking appearance, characterized by a silver to gray body with prominent brown spots concentrated on the dorsal half of the fish and on the fins. Subtle hues of pink are also present around areas such as the mouth and fins. Its broad pectoral fins play a critical role in stabilization, allowing the fish to maintain balance on the ocean floor, while its heterocercal tail, a feature common among cartilaginous fishes, is highly effective for maneuvering within the water column. The asymmetrical structure is essential for tasks such as ascending, descending, and making sharp turns.[3]

As one of the oldest living groups of jawed cartilaginous fishes, C. callorynchus has adapted to its habitat by benthic foraging. Benthic foraging is a method of seeking prey that entails sifting through the sludge of the ocean floor that bottom feeding fish utilize to forage for prey. Its most notable characteristic is its unique sub-terminal plough-shaped snout that is well-adapted for crushing invertebrate prey including scallops, mollusks, and other benthic invertebrates. Its strong jaws contain tooth plates, which are structures in the mouth designed to crush hard-shelled prey, making it an efficient bottom-dwelling predator. Furthermore,Sexual dimorphism is present in this species, with females reaching lengths of up to 102 centimeters and males growing to about 85 centimeters. Upon birth, juveniles measure approximately 13 centimeters in length.[4]

Species Distribution

[edit]Callorhinchus callorynchus is a species predominantly found in the coastal waters of southern Brazil, Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. This species inhabits the open seas of the southeast Pacific Ocean and southwest Atlantic Ocean, with a preferred depth range of approximately 200 meters.[5] However, during their reproductive cycle, including mating and egg-laying periods, these fish are known to migrate to shallow coastal waters. Although they are closely genetically related, it is important not to confuse them with other chimeras because they differ greatly in their preferred location. Other chimeras include the Callorhinchus milii, which found in the sea floors surrounding Australia in the southwest Pacific Ocean, and Callorhinchus capensis, which inhabits waters off the coast of South Africa.

Biology

[edit]The mating and egg-laying cycle of Callorhinchus callorynchus happens primarily in the spring and early summer months, typically in shallow murky waters at depths of around 30 meters. C. callorynchus are oviparous, in which their eggs are internally fertilized and layed to mature and hatch outside of the female body. This reproductive process is highly dependent on water temperature, with optimal conditions ranging between 14 °C and 16 °C. This acts as a biological trigger for the onset of egg-laying. Once fertilized, the embryonic development of this species spans a period of six to eight months.

The eggs themselves are distinctively yellowish-brown in color and spindle-shaped, measuring approximately 13 to 18 centimeters in length. They are also asymmetrical, with one side of the egg being flat and covered in a hairy texture, while the other side is round and smooth, providing additional protection for the developing embryo.[6] The odd shape of the egg is vital for its success in remaining buried within the sediments. Adult females of this species typically reach sexual maturity between six and seven years of age, whereas males mature earlier, usually between four and five years. The relatively late sexual maturity is consistent with the species' lifespan, which averages fifteen to twenty years. This longevity allows for extended growth and development before reproduction.[7] The species exhibits selective feeding behavior based on sex, age, and prey availability, often targeting different species of scallops depending on factors such as prey strength, behavior, and size. This dietary flexibility further highlights its adaptability as a bottom-dwelling predator.[8]

Conservation Status

[edit]The Cockfish is currently listed as vulnerable (VU) on the IUCN Red List, with its population steadily declining due to environmental pressures, particularly overfishing. This species plays a vital role in the Argentine fisheries. It is often caught for its meat and, more concerningly, as bycatch in commercial fishing operations.[9] The pressures from these fisheries are contributing significantly to the decline of this species.

A study conducted by Melisa A. Chierichetti from the National University of Mar del Plata (UNMDP) focused on the reproductive biology of C. callorynchus and revealed important findings. One of the key discoveries was the presence of sexual dimorphism, with females typically being larger and heavier than males within the studied population.[10] The study also highlighted the species' low fecundity rate, a factor that increases its vulnerability. Females were often found in the resting phase of their reproductive cycle, and many of the males had not yet reached sexual maturity, which contributes to the low reproductive output of the population. This information is crucial for the development of conservation strategies, as it emphasizes the need to limit fishing pressures and allow for population recovery.

The vulnerability of C. callorynchus is heightened by several biological and environmental factors. Its tendency to form large aggregations makes it particularly susceptible to overfishing, while its low fecundity rate and late sexual maturity further reduce its ability to recover from population declines. Additionally, global environmental changes pose a significant threat to this species. Rising sea temperatures, driven by climate change, has the potential to disrupt their reproductive cycles. These fish rely on specific water temperatures between 14 °C and 16 °C to trigger their instinctual migration to shallower waters for mating and egg-laying. A recent study indicated that sea surface temperatures have risen by 0.9 °C over the past 37 years, potentially altering the conditions needed for successful reproduction.

Furthermore, the food supply of C. callorynchus is at risk due to coastal pollution, particularly along the Brazilian coastline. Warmer water temperatures have led to an increase in nutrient and bacterial blooms, which negatively impact the populations of scallops, one of the primary prey species for C. callorynchus.[11] As a benthic forager, the elephant fish rely heavily on these invertebrates, and any decline in the benthic population could have negative effects on its food security. This instability in food sources, combined with environmental stresses and fishing pressures, poses a serious threat to the long-term survival of the species.

References

[edit]- ^ Finucci, B.; Cuevas, J.M. (2020). "Callorhinchus callorynchus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T63107A3117894. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T63107A3117894.en. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) 2007. Callorhinchus callorynchus. In: IUCN 2015. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.2. "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. Retrieved 2013-09-28.. Downloaded on 24 July 2015.

- ^ Kim, Sun H.; Shimada, Kenshu; Rigsby, Cynthia K. (2013). "Anatomy and Evolution of Heterocercal Tail in Lamniform Sharks". The Anatomical Record. 296 (3): 433–442. doi:10.1002/ar.22647. PMID 23381874.

- ^ Chierichetti, Melisa A.; Scenna, Lorena B.; Giácomo, Edgardo E. Di; Ondarza, Paola M.; Figueroa, Daniel E.; Miglioranza, Karina S. B. (2017). "Reproductive biology of the cockfish, Callorhinchus callorynchus (Chondrichthyes: Callorhinchidae), in coastal waters of the northern Argentinean Sea". Neotropical Ichthyology. 15 (2). doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20160137. hdl:11336/64515.

- ^ Rizzari, Justin R.; Finucci, Brittany (2019). "Elephantfish". Current Biology. 29 (10): R352–R353. Bibcode:2019CBio...29.R352R. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.021. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30121990. PMID 31112680.

- ^ Mabragaña, E., et al. “Chondrichthyan egg cases from the south‐west Atlantic Ocean.” Journal of Fish Biology, vol. 79, no. 5, 25 Oct. 2011, pp. 1261–1290, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03111.x

- ^ Alarcón, Carolina; Cubillos, Luis A.; Acuña, Enzo (2011). "Length-based growth, maturity and natural mortality of the cockfish Callorhinchus callorhynchus (Linnaeus, 1758) off Coquimbo, Chile". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 92 (1): 65–78. Bibcode:2011EnvBF..92...65A. doi:10.1007/s10641-011-9816-0.

- ^ Di Giacomo, EE; Perier, MR (1996). "Feeding habits of cockfish, Callorhinchus callorhynchus (Holocephali: Callorhynchidae), in Patagonian waters (Argentina)". Marine and Freshwater Research. 47 (6): 801. doi:10.1071/mf9960801.

- ^ Chierichetti, Melisa A.; Scenna, Lorena B.; Giácomo, Edgardo E. Di; Ondarza, Paola M.; Figueroa, Daniel E.; Miglioranza, Karina S. B. (2017). "Reproductive biology of the cockfish, Callorhinchus callorynchus (Chondrichthyes: Callorhinchidae), in coastal waters of the northern Argentinean Sea". Neotropical Ichthyology. 15 (2). doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20160137. hdl:11336/64515.

- ^ Chierichetti, Melisa A.; Scenna, Lorena B.; Giácomo, Edgardo E. Di; Ondarza, Paola M.; Figueroa, Daniel E.; Miglioranza, Karina S. B. (2017). "Reproductive biology of the cockfish, Callorhinchus callorynchus (Chondrichthyes: Callorhinchidae), in coastal waters of the northern Argentinean Sea". Neotropical Ichthyology. 15 (2). doi:10.1590/1982-0224-20160137. hdl:11336/64515.

- ^ Thompson, Cristiane, et al. “Collapse of scallop nodipecten nodosus production in the tropical southeast Brazil as a possible consequence of global warming and water pollution.” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 904, Dec. 2023, p. 166873, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166873