Difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was first created by Charles Babbage. The name difference engine is derived from the method of divided differences, a way to interpolate or tabulate functions by using a small set of polynomial co-efficients. Some of the most common mathematical functions used in engineering, science and navigation are built from logarithmic and trigonometric functions, which can be approximated by polynomials, so a difference engine can compute many useful tables.

History

[edit]

The notion of a mechanical calculator for mathematical functions can be traced back to the Antikythera mechanism of the 2nd century BC, while early modern examples are attributed to Pascal and Leibniz in the 17th century.

In 1784 J. H. Müller, an engineer in the Hessian army, devised and built an adding machine and described the basic principles of a difference machine in a book published in 1786 (the first written reference to a difference machine is dated to 1784), but he was unable to obtain funding to progress with the idea.[1][2][3]

Charles Babbage's difference engines

[edit]Charles Babbage began to construct a small difference engine in c. 1819[4] and had completed it by 1822 (Difference Engine 0).[5] He announced his invention on 14 June 1822, in a paper to the Royal Astronomical Society, entitled "Note on the application of machinery to the computation of astronomical and mathematical tables".[6] This machine used the decimal number system and was powered by cranking a handle. The British government was interested, since producing tables was time-consuming and expensive and they hoped the difference engine would make the task more economical.[7]

In 1823, the British government gave Babbage £1700 to start work on the project. Although Babbage's design was feasible, the metalworking techniques of the era could not economically make parts in the precision and quantity required. Thus the implementation proved to be much more expensive and doubtful of success than the government's initial estimate. According to the 1830 design for Difference Engine No. 1, it would have about 25,000 parts, weigh 4 tons,[8] and operate on 20-digit numbers by sixth-order differences. In 1832, Babbage and Joseph Clement produced a small working model (one-seventh of the plan),[5] which operated on 6-digit numbers by second-order differences.[9][10] Lady Byron described seeing the working prototype in 1833: "We both went to see the thinking machine (or so it seems) last Monday. It raised several Nos. to the 2nd and 3rd powers, and extracted the root of a Quadratic equation."[11] Work on the larger engine was suspended in 1833.

By the time the government abandoned the project in 1842,[10][12] Babbage had received and spent over £17,000 on development, which still fell short of achieving a working engine. The government valued only the machine's output (economically produced tables), not the development (at unpredictable cost) of the machine itself. Babbage refused to recognize that predicament.[7] Meanwhile, Babbage's attention had moved on to developing an analytical engine, further undermining the government's confidence in the eventual success of the difference engine. By improving the concept as an analytical engine, Babbage had made the difference engine concept obsolete, and the project to implement it an utter failure in the view of the government.[7]

The incomplete Difference Engine No. 1 was put on display to the public at the 1862 International Exhibition in South Kensington, London.[13][14]

Babbage went on to design his much more general analytical engine, but later designed an improved "Difference Engine No. 2" design (31-digit numbers and seventh-order differences),[9] between 1846 and 1849. Babbage was able to take advantage of ideas developed for the analytical engine to make the new difference engine calculate more quickly while using fewer parts.[15][16]

Scheutzian calculation engine

[edit]

Inspired by Babbage's difference engine in 1834, Per Georg Scheutz built several experimental models. In 1837 his son Edward proposed to construct a working model in metal, and in 1840 finished the calculating part, capable of calculating series with 5-digit numbers and first-order differences, which was later extended to third-order (1842). In 1843, after adding the printing part, the model was completed.

In 1851, funded by the government, construction of the larger and improved (15-digit numbers and fourth-order differences) machine began, and finished in 1853. The machine was demonstrated at the World's Fair in Paris, 1855 and then sold in 1856 to the Dudley Observatory in Albany, New York. Delivered in 1857, it was the first printing calculator sold.[17][18][19] In 1857 the British government ordered the next Scheutz's difference machine, which was built in 1859.[20][21] It had the same basic construction as the previous one, weighing about 10 cwt (1,100 lb; 510 kg).[19]

Others

[edit]Martin Wiberg improved Scheutz's construction (c. 1859, his machine has the same capacity as Scheutz's: 15-digit and fourth-order) but used his device only for producing and publishing printed tables (interest tables in 1860, and logarithmic tables in 1875).[22]

Alfred Deacon of London in c. 1862 produced a small difference engine (20-digit numbers and third-order differences).[17][23]

American George B. Grant started working on his calculating machine in 1869, unaware of the works of Babbage and Scheutz (Schentz). One year later (1870) he learned about difference engines and proceeded to design one himself, describing his construction in 1871. In 1874 the Boston Thursday Club raised a subscription for the construction of a large-scale model, which was built in 1876. It could be expanded to enhance precision and weighed about 2,000 pounds (910 kg).[23][24][25]

Christel Hamann built one machine (16-digit numbers and second-order differences) in 1909 for the "Tables of Bauschinger and Peters" ("Logarithmic-Trigonometrical Tables with eight decimal places"), which was first published in Leipzig in 1910. It weighed about 40 kilograms (88 lb).[23][26][27]

Burroughs Corporation in about 1912 built a machine for the Nautical Almanac Office which was used as a difference engine of second-order.[28]: 451 [29] It was later replaced in 1929 by a Burroughs Class 11 (13-digit numbers and second-order differences, or 11-digit numbers and [at least up to] fifth-order differences).[30]

Alexander John Thompson about 1927 built integrating and differencing machine (13-digit numbers and fifth-order differences) for his table of logarithms "Logarithmetica britannica". This machine was composed of four modified Triumphator calculators.[31][32][33]

Leslie Comrie in 1928 described how to use the Brunsviga-Dupla calculating machine as a difference engine of second-order (15-digit numbers).[28] He also noted in 1931 that National Accounting Machine Class 3000 could be used as a difference engine of sixth-order.[23]: 137–138

Construction of two working No. 2 difference engines

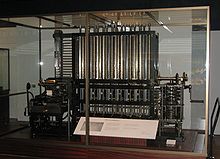

[edit]During the 1980s, Allan G. Bromley, an associate professor at the University of Sydney, Australia, studied Babbage's original drawings for the Difference and Analytical Engines at the Science Museum library in London.[34] This work led the Science Museum to construct a working calculating section of difference engine No. 2 from 1985 to 1991, under Doron Swade, the then Curator of Computing. This was to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Babbage's birth in 1991. In 2002, the printer which Babbage originally designed for the difference engine was also completed.[35] The conversion of the original design drawings into drawings suitable for engineering manufacturers' use revealed some minor errors in Babbage's design (possibly introduced as a protection in case the plans were stolen),[36] which had to be corrected. The difference engine and printer were constructed to tolerances achievable with 19th-century technology, resolving a long-standing debate as to whether Babbage's design could have worked using Georgian-era engineering methods. The machine contains 8,000 parts and weighs about 5 tons.[37]

The printer's primary purpose is to produce stereotype plates for use in printing presses, which it does by pressing type into soft plaster to create a flong. Babbage intended that the Engine's results be conveyed directly to mass printing, having recognized that many errors in previous tables were not the result of human calculating mistakes but from slips in the manual typesetting process.[7] The printer's paper output is mainly a means of checking the engine's performance.

In addition to funding the construction of the output mechanism for the Science Museum's difference engine, Nathan Myhrvold commissioned the construction of a second complete Difference Engine No. 2, which was on exhibit at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, from May 2008 to January 2016.[37][38][39][40] It has since been transferred to Intellectual Ventures in Seattle where it is on display just outside the main lobby.[41][42][43]

Operation

[edit]

The difference engine consists of a number of columns, numbered from 1 to N. The machine is able to store one decimal number in each column. The machine can only add the value of a column n + 1 to column n to produce the new value of n. Column N can only store a constant, column 1 displays (and possibly prints) the value of the calculation on the current iteration.

The engine is programmed by setting initial values to the columns. Column 1 is set to the value of the polynomial at the start of computation. Column 2 is set to a value derived from the first and higher derivatives of the polynomial at the same value of X. Each of the columns from 3 to N is set to a value derived from the first and higher derivatives of the polynomial. [44]

Timing

[edit]In the Babbage design, one iteration (i.e. one full set of addition and carry operations) happens for each rotation of the main shaft. Odd and even columns alternately perform an addition in one cycle. The sequence of operations for column is thus:[44]

- Count up, receiving the value from column (Addition step)

- Perform carry propagation on the counted up value

- Count down to zero, adding to column

- Reset the counted-down value to its original value

Steps 1,2,3,4 occur for every odd column, while steps 3,4,1,2 occur for every even column.

While Babbage's original design placed the crank directly on the main shaft, it was later realized that the force required to crank the machine would have been too great for a human to handle comfortably. Therefore, the two models that were built incorporate a 4:1 reduction gear at the crank, and four revolutions of the crank are required to perform one full cycle.

Steps

[edit]Each iteration creates a new result, and is accomplished in four steps corresponding to four complete turns of the handle shown at the far right in the picture below. The four steps are:

- All even numbered columns (2,4,6,8) are added to all odd numbered columns (1,3,5,7) simultaneously. An interior sweep arm turns each even column to cause whatever number is on each wheel to count down to zero. As a wheel turns to zero, it transfers its value to a sector gear located between the odd/even columns. These values are transferred to the odd column causing them to count up. Any odd column value that passes from "9" to "0" activates a carry lever.

- This is like Step 1, except it is odd columns (3,5,7) added to even columns (2,4,6), and column one has its values transferred by a sector gear to the print mechanism on the left end of the engine. Any even column value that passes from "9" to "0" activates a carry lever. The column 1 value, the result for the polynomial, is sent to the attached printer mechanism.

- This is like Step 2, but for doing carries on even columns, and returning odd columns to their original values.

Subtraction

[edit]The engine represents negative numbers as ten's complements. Subtraction amounts to addition of a negative number. This works in the same manner that modern computers perform subtraction, known as two's complement.

Method of differences

[edit]The principle of a difference engine is Newton's method of divided differences. If the initial value of a polynomial (and of its finite differences) is calculated by some means for some value of X, the difference engine can calculate any number of nearby values, using the method generally known as the method of finite differences. For example, consider the quadratic polynomial

with the goal of tabulating the values p(0), p(1), p(2), p(3), p(4), and so forth. The table below is constructed as follows: the second column contains the values of the polynomial, the third column contains the differences of the two left neighbors in the second column, and the fourth column contains the differences of the two neighbors in the third column:

| x | p(x) = 2x2 − 3x + 2 | diff1(x) = ( p(x + 1) − p(x) ) | diff2(x) = ( diff1(x + 1) − diff1(x) ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | −1 | 4 |

| 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| 3 | 11 | 11 | |

| 4 | 22 |

The numbers in the third values-column are constant. In fact, by starting with any polynomial of degree n, the column number n + 1 will always be constant. This is the crucial fact behind the success of the method.

This table was built from left to right, but it is possible to continue building it from right to left down a diagonal in order to compute more values. To calculate p(5) use the values from the lowest diagonal. Start with the fourth column constant value of 4 and copy it down the column. Then continue the third column by adding 4 to 11 to get 15. Next continue the second column by taking its previous value, 22 and adding the 15 from the third column. Thus p(5) is 22 + 15 = 37. In order to compute p(6), we iterate the same algorithm on the p(5) values: take 4 from the fourth column, add that to the third column's value 15 to get 19, then add that to the second column's value 37 to get 56, which is p(6). This process may be continued ad infinitum. The values of the polynomial are produced without ever having to multiply. A difference engine only needs to be able to add. From one loop to the next, it needs to store 2 numbers—in this example (the last elements in the first and second columns). To tabulate polynomials of degree n, one needs sufficient storage to hold n numbers.

Babbage's difference engine No. 2, finally built in 1991, can hold 8 numbers of 31 decimal digits each and can thus tabulate 7th degree polynomials to that precision. The best machines from Scheutz could store 4 numbers with 15 digits each.[45]

Initial values

[edit]The initial values of columns can be calculated by first manually calculating N consecutive values of the function and by backtracking (i.e. calculating the required differences).

Col gets the value of the function at the start of computation . Col is the difference between and ...[46]

If the function to be calculated is a polynomial function, expressed as

the initial values can be calculated directly from the constant coefficients a0, a1,a2, ..., an without calculating any data points. The initial values are thus:

- Col = a0

- Col = a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + ... + an

- Col = 2a2 + 6a3 + 14a4 + 30a5 + ...

- Col = 6a3 + 36a4 + 150a5 + ...

- Col = 24a4 + 240a5 + ...

- Col = 120a5 + ...

Use of derivatives

[edit]Many commonly used functions are analytic functions, which can be expressed as power series, for example as a Taylor series. The initial values can be calculated to any degree of accuracy; if done correctly the engine will give exact results for first N steps. After that, the engine will only give an approximation of the function.

The Taylor series expresses the function as a sum obtained from its derivatives at one point. For many functions the higher derivatives are trivial to obtain; for instance, the sine function at 0 has values of 0 or for all derivatives. Setting 0 as the start of computation we get the simplified Maclaurin series

The same method of calculating the initial values from the coefficients can be used as for polynomial functions. The polynomial constant coefficients will now have the value

Curve fitting

[edit]The problem with the methods described above is that errors will accumulate and the series will tend to diverge from the true function. A solution which guarantees a constant maximum error is to use curve fitting. A minimum of N values are calculated evenly spaced along the range of the desired calculations. Using a curve fitting technique like Gaussian reduction an N−1th degree polynomial interpolation of the function is found.[46] With the optimized polynomial, the initial values can be calculated as above.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johann Helfrich von Müller, Beschreibung seiner neu erfundenen Rechenmachine, nach ihrer Gestalt, ihrem Gebrauch und Nutzen [Description of his newly invented calculating machine, according to its form, its use and benefit] (Frankfurt and Mainz, Germany: Varrentrapp Sohn & Wenner, 1786); pages 48–50. The following Web site (in German) contains detailed photos of Müller's calculator as well as a transcription of Müller's booklet, Beschreibung …: https://www.fbi.h-da.de/fileadmin/vmi/darmstadt/objekte/rechenmaschinen/mueller/index.htm Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine . An animated simulation of Müller's machine in operation is available on this Web site (in German): https://www.fbi.h-da.de/fileadmin/vmi/darmstadt/objekte/rechenmaschinen/mueller/simulation/index.htm Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine .

- ^ Michael Lindgren (Craig G. McKay, trans.), Glory and Failure: The Difference Engines of Johann Müller, Charles Babbage, and Georg and Edvard Scheutz (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1990), pages 64 ff.

- ^ Swedin, E.G.; Ferro, D.L. (2005). Computers: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-313-33149-7.

- ^ Dasgupta, Subrata (2014). It Began with Babbage: The Genesis of Computer Science. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-930943-6.

- ^ a b Copeland, B. Jack; Bowen, Jonathan P.; Wilson, Robin; Sprevak, Mark (2017). The Turing Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780191065002.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1998). "Charles Babbage". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Archived from the original on 2006-06-16. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- ^ a b c d Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2004). Computer: A History of the Information Machine 2nd ed. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4264-1.

- ^ "The Engines | Babbage Engine". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ^ a b O'Regan, Gerard (2012). A Brief History of Computing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-4471-2359-0.

- ^ a b Snyder, Laura J. (2011). The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World. Crown/Archetype. pp. 192, 210, 217. ISBN 978-0-307-71617-0.

- ^ Toole, Betty Alexandra; Lovelace, Ada (1998). Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers. Mill Valley, California: Strawberry Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0912647180. OCLC 40943907.

- ^ Weld, Charles Richard (1848). A History of the Royal Society: With Memoirs of the Presidents. J. W. Parker. pp. 387–390.

- ^ Tomlinson, Charles (1868). Cyclopaedia of useful arts, mechanical and chemical, manufactures, mining and engineering: in three volumes, illustrated by 63 steel engravings and 3063 wood engravings. Virtue & Co. p. 136.

- ^ Official catalogue of the industrial department. 1862. p. 49.

- ^ Snyder, Laura J. (2011). The Philosophical Breakfast Club. New York: Broadway Brooks. ISBN 978-0-7679-3048-2.

- ^ Morris, Charles R. (October 23, 2012). The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution. PublicAffairs. p. 63. ISBN 9781610393577.

- ^ a b Scheutz, George; Scheutz, Edward (1857). Specimens of Tables, Calculated, Stereomoulded, and Printed by Machinery. Whitnig. pp. VIII–XII, XIV–XV, 3.

- ^ "Scheutz Difference Engine". Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Merzbach, Uta C.; Ripley, S. Dillon; Merzbach, Uta C. First Printing Calculator. pp. 8–9, 13, 25–26, 29–30. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.639.3286.

- ^ Swade, Doron (2002-10-29). The Difference Engine: Charles Babbage and the Quest to Build the First Computer. Penguin Books. pp. 4, 207. ISBN 9780142001448.

- ^ Watson, Ian (2012). The Universal Machine: From the Dawn of Computing to Digital Consciousness. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-3-642-28102-0.

- ^ Archibald, Raymond Clare (1947). "Martin Wiberg, His Table and Difference Engine" (PDF). Mathematical Tables and Other Aids to Computation. 2 (20): 371–374.

- ^ a b c d Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003). The History of Mathematical Tables: From Sumer to Spreadsheets. OUP Oxford. pp. 132–136. ISBN 978-0-19-850841-0.

- ^ "History of Computers and Computing, Babbage, Next differential engines, Hamann". history-computer.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ^ Sandhurst, Phillip T. (1876). The Great Centennial Exhibition Critically Described and Illustrated. P. W. Ziegler & Company. pp. 423, 427.

- ^ Bauschinger, Julius; Peters, Jean (1958). Logarithmisch-trigonometrische Tafeln mit acht Dezimalstellen, enthaltend die Logarithmen aller Zahlen von 1 bis 200000 und die Logarithmen der trigonometrischen Funktionen f"ur jede Sexagesimalsekunde des Quadranten: Bd. Tafel der achtstelligen Logarithmen aller Zahlen von 1 bis 200000. H. R. Engelmann. pp. Preface V–VI.

- ^ Bauschinger, Julius; Peters, J. (Jean) (1910). Logarithmisch-trigonometrische Tafeln, mit acht Dezimalstellen, enthaltend die Logarithmen aller Zahlen von 1 bis 200000 und die Logarithmen der trigonometrischen Funktionen für jede Sexagesimalsekunde des Quadranten. Neu berechnet und hrsg. von J. Bauschinger und J. Peters. Stereotypausg (in German). Gerstein - University of Toronto. Leipzig W. Englemann. pp. Einleitung VI.

- ^ a b Comrie, L. J. (1928-03-01). "On the application of the BrunsvigaDupla calculating machine to double summation with finite differences". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 88 (5): 451, 453–454, 458–459. Bibcode:1928MNRAS..88..447C. doi:10.1093/mnras/88.5.447. ISSN 0035-8711 – via Astrophysics Data System.

- ^ Horsburg, E. M. (1914). Modern instruments and methods of calculation : a handbook of the Napier Tercentenary Exhibition. London: G. Bell. pp. 127–131.

- ^ Comrie, L. J. (1932-04-01). "The Nautical Almanac Office Burroughs machine". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (6): 523–524, 537–538. Bibcode:1932MNRAS..92..523C. doi:10.1093/mnras/92.6.523. ISSN 0035-8711 – via Astrophysics Data System.

- ^ Thompson, Alexander John (1924). Logarithmetica Britannica: Being a Standard Table of Logarithms to Twenty Decimal Places. CUP Archive. pp. V/VI, XXIX, LIV–LVI, LXV (archive: pp. 7, 30, 55–59, 68). ISBN 9781001406893. Alt URL

- ^ "History of Computers and Computing, Babbage, Next differential engines, Alexander John Thompson". history-computer.com. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ^ Weiss, Stephan. "Publikationen". mechrech.info. Difference Engines in the 20th Century. First published in Proceedings 16th International Meeting of Collectors of Historical Calculating Instruments, Sep. 2010, Leiden. pp. 160–163. Retrieved 2017-09-22.

- ^ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 22(4), October–December 2000.

- ^ "A Modern Sequel | Babbage Engine". Computer History Museum.

- ^ Babbage printer finally runs, BBC news quoting Reg Crick Accessed May 17, 2012

- ^ a b Press Releases | Computer History

- "The Computer History Museum Debuts Charles Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2, On Display for the First Time in North America" (Press release). Computer History Museum. 2008-05-05. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- "The Computer History Museum Extends Its Exhibition of Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2" (Press release). Computer History Museum. March 31, 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-01-03. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ^ "The Babbage Difference Engine No. 2". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- ^ Terdiman, Daniel (April 10, 2008). "Charles Babbage's masterpiece difference engine comes to Silicon Valley". CNET News.

- ^ Noack, Mark (29 January 2016). "Computer Museum bids farewell to Babbage engine". Mv-voice.com. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (2016-09-11). "Inside the invention factory: Get a peek at Intellectual Ventures' lab". Retrieved 2024-04-21.

- ^ "Intellectual Ventures on LinkedIn: #ivlab #coolscience". www.linkedin.com. Retrieved 2024-04-21.

- ^ Ventures, Intellectual (September 1, 2016). "IV's Favorite Inventions: The Babbage Machine". Intellectual Ventures. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Lardner, D. (July 1834). "Babbage's Calculating Engine". Edinburgh Review: 263–327. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

In WikiSource and also reprinted in The works of Charles Babbage, Vol 2, p.119ff

- ^ O'Regan, Gerard (2012). A Brief History of Computing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4471-2359-0.

- ^ a b Thelen, Ed (2008). "Babbage Difference Engine #2 – How to Initialize the Machine –".

Further reading

[edit]- Snyder, Laura J. (2011). The Philosophical Breakfast Club: Four Remarkable Friends Who Transformed Science and Changed the World. Broadway. ISBN 978-0-7679-3048-2.

- Swade, Doron (September 1996). Charles Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 – Technical Description. Science Museum Papers in the History of Technology No 5. London: National Museum of Science and Industry. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- Swade, Doron (2002). The Difference Engine: Charles Babbage and the Quest to Build the First Computer. Penguin (reprint). ISBN 978-0-14-200144-8.

- Swade, Doron (2001). The Cogwheel Brain. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11239-8.

- Doron Swade, Nathan Myhrvold (June 10, 2008). Myhrvold & Swade Discuss Babbage's Difference Engine (lecture: Len Shustek, intro; Doron Swade @7:35, Nathan Myhrvold @36:25; discussion @46:45). Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003). "Difference engines: from Müller to Comrie". The History of Mathematical Tables: From Sumer to Spreadsheets. Michael R. Williams. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780198508410.

External links

[edit]- The Computer History Museum exhibition on Babbage and the difference engine

- Meccano Difference Engine #1

- Meccano Difference Engine #2

- Babbage's First Difference Engine – How it was intended to work

- Analysis of Expenditure on Babbage's Difference Engine No. 1

- Difference engine workings with animations

- Difference Engine No1 specimen piece at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

- Gigapixel Image of the Difference Engine No2

- Scheutz Difference Engine in action video. Purchased by the Dudley Observatory's first director, Benjamin Apthorp Gould, in 1856. Gould was an acquaintance of Babbage. The Difference Engine performed astronomical calculations for the Observatory for many years, and is now part of the national collection at the Smithsonian.

- Links to videos about Babbage DE 2 and its construction: "Computer Histories: To Learn More". www.computerhistories.org. Topic 5 - Computers in the Steam Era (Not Hackers But Clackers).