Caciquism

Caciquism is a network of political power wielded by local leaders called "caciques", aimed at influencing electoral outcomes. It is a feature of some modern-day societies with incomplete democratization.[1][2]

In historiography, journalism, and intellectual circles of the era, the term describes the political system of the Bourbon Restoration in Spain (1874-1923). Joaquín Costa's influential essay Oligarchie et Caciquisme ("Oligarchy and Caciquism") in 1901 popularized the term.[3] Nonetheless, caciquism was also prevalent in earlier periods in the country, particularly during the reign of Isabella II.[4] It was also utilized in other systems, such as in Portugal during the Constitutional Monarchy (1820-1910)[5] as well as in Argentina[6] and Mexico[7] during a similar time period.

Concept of "cacique"

[edit]The term "cacique" in Spanish, as well as other Western languages like French, stems from the Arawak term kassequa. It referred specifically to the individuals who had the highest ranking within the Taino tribes of the West Indies and thus held the title of chief. This linguistic borrowing highlights the historical and cultural connections between these various groups.[6]

Brought back by Christopher Columbus upon his return from his first voyage to America in 1492,[8][9] the conquistadors utilized the term and expanded its usage to include the Central American setting and other indigenous groups they encountered,[6][7] even up to the absolute rulers of the pre-Columbian empires.[10]

The concept of "cacique" differs from "seigneur" or "señor," which originated from feudalism, in its hierarchical inferiority. Caciques serve as privileged intermediaries and main interlocutors between the authority of the "masters" or "seigneurs" (conquistadors) and the populations they aim to control. A distinction was drawn between the "good caciques" who cooperated obediently with colonial and ecclesiastical authorities - the encomenderos, and the "bad caciques" who needed to be subdued or dismissed.[11] The term remained in use to "indicate the contrast between the conqueror's authority and the authorities of the defeated".[12] Certainly, "the role of the cacique was to bridge the gap between the Indian population and colonial administration." At the same time, his power in the community was based on his positive relations with the central administration. This allowed him to provide service not only for himself but also for the local administration.[13]

At least since the eighteenth century, the term has had a broader meaning of "a dominating individual who instills fear and holds influence in a locality," with a negative connotation within the peninsular context. The term "cacique" appears in the 1729 Diccionario de Autoridades, where it is defined as the "Lord of the vassals, or the Superior in the Province or Pueblos de Indios". Additionally, the definition explains that the term is used metaphorically to refer to the first leader of a Pueblo or Republic who wields more power and commands more respect by being feared and obeyed by those beneath them. As a result, the term came to be applied to individuals who have an overly influential and powerful role in a community.[11][14]

In the 1884 edition of the Royal Spanish Academy's Diccionario de la lengua española, the term appears with its current meaning, which encompasses both:

- The domination or influence of the cacique of a town or comarca.

- The abusive interference of a person or authority in certain matters, using his power or influence.

The influence of the cacique extends beyond the political sphere and encompasses all human interactions. Consequently, the term "cacique" has evolved into a timeless and universal concept, applicable to any societal group and context in reference to power dynamics that involve patronage, clientelism, paternalism, dependence, favors, punishments, thanks, and curses among unequal individuals.[11] The "good cacique" serves as a protective figure, dispensing favors, and contrasts with the "bad cacique" who represses, excludes, or deprives.[15]

Related terms

[edit]During the time, the Spanish press utilized the term "caudillismo" (caudillismo or caudillaje) interchangeably with "caciquism" to describe the rule of the caciques, who were then referred to as "caudillos".[6]

The term "cacicada", meaning "injustice, arbitrary action [by a cacique]", is also derived from "cacique".[16][17]

Contemporary uses

[edit]In soccer circles, Argentine defender Iselín Santos Ovejero was nicknamed el cacique del área ("the cacique of the penalty area") in Spanish.[15]

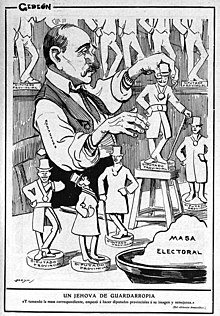

In Spain

[edit]"Caciquism" in Spain refers to the clientelist network that shaped the political regime of the Restoration, enabling fraud in all general elections. However, this system had also existed during Isabel II's liberal period and the democratic sexennium.[18] They were able to "manufacture" elections at the central power's whim to ensure political alternation between the conservative and liberal parties, known as the "dynastic parties." This made them a crucial link during the era.[19][20]

During the Bourbon Restoration, the term "cacique" referred to influential figures in specific areas. "Nothing was accomplished without his agreement, and never any actions against him. The power of the cacique was immense in spite of his unofficial role. In cases of conflict with the civil governor - the representative of central authority - the cacique held the final say."[21] With the local population under his control and votes not taking place via secret ballot -a phenomenon not unique to Spain- the cacique could easily determine the outcome of elections.[22]

In the boss/customer relationship, Manuel Suárez Cortina points out that an individual in a superior position (boss) provides protection or benefits to a person in an inferior position (customer) by leveraging their resources and influence. In exchange, the customer reciprocates by offering general support, assistance, and sometimes even personal services.[23] On the other hand, clienteles generally remain indifferent to ideologies, programs, or political affiliations in regards to their collective projection. "And this tendency, of course, reduced the ideological aspects of politics," observes José Varela Ortega. Furthermore, clients anticipated receiving personal favors.[24]

Alongside "oligarchy," the term "caciquism" commonly depicted the political regime during the Restoration era. José Varela Ortega positions the beginning of the caciquist system near 1845, prior to which the administration held less sway compared to after that time. Caciquism dominated the dispute between local and central administration, specifically local notables versus caciques and landowners versus civil servants. The Caciquist era of interference by administration and party officials against local notables began after 1845 due to centralization and single-member districts. In 1850, the Count of San Luis established the "Family Assemblies [Cortes]," which ushered in the era of administrative or royal elections. The government actively intervened in the elections. In other words, the government exerted "leadership" rather than "legitimate influence," as the 1930s notables were labeled.[25]

With this in mind, Varela Ortega states that Cánovas did not invent caciquism.[26] Rather, it was already present and was distributed more systematically during the Restoration. However, starting in 1850 and particularly in the 1860s and 1870s, the government interfered in elections, taking the place of a non-existent electorate. Similarly, party organizations exploited the administration for their own partisan goals, just as they did during the Restoration.[25]

Some scholars argue that the political system during Isabella II's reign was an extreme example of oligarchy, as evidenced by censal suffrage laws that restricted the vote only to large and, occasionally, medium-sized landowners. The political system in Isabelline Spain was largely controlled by caciques, as evidenced by the fact that the party that called the majority of the twenty-two elections held during this period was consistently victorious.[27] Furthermore, clientelist political relationships had become well-established in the mid-nineteenth century and persisted throughout the democratic sexennium without being eliminated, as no government during this time was voted out of power. "When the political system of the Restoration was established, clientelism had already been present in Spain for a significant period of time."[28]

Caciquism and Restoration

[edit]Although the term "caciquism" was used early to refer to the political regime of the Restoration, and people were already criticizing the "disgusting scourge of caciquism" at the 1891 general elections,[30] which were won by the government, it wasn't until the "disaster of [18]98" that the term became widely used. In that same year, liberal Santiago Alba was already attributing the disaster to "unbearable caciquism".[31]

Caciquism played a significant role in rural areas, particularly until the end of the regime. Although the caciquist system was criticized by supporters of reformation and disapproved in the big cities and public opinion, such criticisms held minimal impact in most of the country. The local poor even tolerated the system, with few families in one small town that didn't have at least one member involved.[32] In the end, caciquism was enabled by the apathy its actions aroused among the majority, as well as the ineffective mobilization of a significant portion of the voting population.[33]

In 1901, the Ateneo de Madrid conducted a survey and debate focused on Spain's socio-political system, with the participation of around sixty politicians and intellectuals. Joaquín Costa, a regenerationist, summarized the discussion in his work titled Oligarchy and Caciquism as Representing the Current Form of Government in Spain. Urgency and potential solutions. To address this issue, urgent action is required. In his work, Costa argues that Spain's political landscape is dominated by an oligarchy, with no true representation or political parties. This minority's interests solely serve their own, creating an unjust ruling class. The oligarchy's top executives, or "primates", consist of professional politicians based in Madrid, the center of power. This group is supported by a vast network of "caciques" scattered throughout the country, who hold varying degrees of power and influence. The relationship between the dominant "primates" and the regional caciques was established by the civil governors. In his report, Costa maintained that oligarchy and caciquism were not anomalies in the system, but rather the norm and the governing structure itself. The majority of participants in the survey-debate concurred with this assertion, which remains a widely held perspective today. More than a century later, Carmelo Romero Salvador notes that Costa's two-word description, which has become the title of historical literature and manuals, remains the most commonly used term to depict the Restorationist period.[34]

As an illustration, José María Jover, in a university textbook frequently used in the 1960s and 1970s, characterized the Restoration regime in the following manner:

"We are, therefore, in the presence of a constitutional reality that is certainly not foreseen in the written text of the Constitution. This reality is based on two de facto institutions. On the one hand, on the existence of an oligarchy or ruling political minority, made up of men from both parties (ministers, senators, deputies, civil governors, owners of press titles...) and closely connected both by its social extraction and by its family and social relations with the dominant social groups (landowners, blood nobility, business bourgeoisie, etc.). On the other hand, in a kind of seigneurial survival in rural milieus, by virtue of which certain figures in the town or locality, distinguished by their economic power, administrative function, prestige or "influence" with the oligarchy, directly control large groups of people; this seigneurial survival will be called caciquism. The "politician" in Madrid; the "cacique" in each comarca; the civil governor in the capital of each province as a link between the one and the other, constitute the three key pieces in the actual functioning of the system."

Manuel Suárez Cortina notes that Costa and other critics of the Restoration system, like Gumersindo de Azcárate, viewed the political operations of the era as a new form of feudalism, wherein the political will of the citizens was hijacked for the profit of the elite: an oligarchy that abused the nation's true will through election fraud and corruption. The "interpretative line" was reinforced in Marxist and liberal Spanish historiography.[35] A comparable interpretation of Costa's analysis is shared by Joaquín Romero Maura, cited by Feliciano Montero, who also agrees that it was the most commonly used explanation for the phenomenon of caciquism during the Restoration era in Spain. According to Romero Maura, Costa and those who share his interpretation view caciquismo as a political manifestation of the economic dominance of landed and financial elites. This phenomenon is facilitated by a disengaged electorate, which is a result of the low level of economic development and social integration in various regions of the country, including factors such as poor communication, a closed economy, and high illiteracy rates.[36]

In the early 1970s, a new perspective on caciquism emerged among historians, including Joaquín Romero Maura, José Varela Ortega, and Javier Tusell. This perspective, which is now the dominant one, focuses exclusively on political factors and views caciquism as the outcome of patron-client relationships.[37] According to Suárez Cortina, the interpretation's most distinctive components emphasize the non-economic aspect of the patron-client relationship, the electorate's widespread demobilization, the predominance of rural components vis-à-vis urban components, and the varied nature of relations and exchanges between patrons and clients across different times and places - altogether constituting the key features that characterize patronage relations.[38]

Functioning

[edit]Caciques, like politicians of their time, are seldom personally corrupt. They typically do not seek personal gain through corruption. Rather, corruption resides in the structures of the system, where the state and its resources serve an oligarchy, of which the cacique is a vital component.[39]

The central role of a cacique, who typically lacks an official position and may not be a powerful figure, is to act as an intermediary between the Administration and their extensive clientele from all social strata. They consistently pursue fulfilling the interests of their clients through illicit measures, as "caciquism feeds on illegality". The caciques serve as intermediaries, serving as the missing links between a deficient state and its constituents who are physically and symbolically distant.[21][40] Within the individual beneficiaries or recipients of favors, there are those who obtain an exemption from military service and those who receive a lower assessment of taxable wealth. On the other hand, certain benefits are accrued either to the public at large (such as a highway, railroad crossing, or educational institutions) or to the well-being of a specific socio-economic group, with a cacique positioned at its helm to cement their position.[41] To illustrate, Asturias boasted a truly deluxe network of roads during the early 20th century thanks to cacique Alejandro Pidal y Mon and his son Pedro.[39] Similarly, Juan de la Cierva y Peñafiel established the University of Murcia in 1914.[39]

Electoral fraud, such as ballot box stuffing, replacement, and the use of deceased individuals' votes,[42] is typically orchestrated by the cacique (pucherazo).[1]

The cacique's influence, derived from an array of resources including economic, administrative, fiscal, academic, and medical, is the foundation of their client base. The cacique operates through arrangements for those who serve him and coercion, including pressure, threats, and blackmail for others. He can create or eliminate jobs, open or close businesses, manipulate local justice and administration,[43] obtain exemptions from military obligations, misappropriate taxes to benefit local politicians, allow discreet purchases of essential goods without payment of consumos,[44] assist with administrative procedures, facilitate the creation of new infrastructure like roads or schools,[40] and lend his own money. He provides loans without interest, either personally or on behalf of the State. He is not in a rush to be reimbursed as his benevolence gains him the appreciation of the common folk who seek his guidance and, naturally, follow his lead at the polls.[21]

The local political leader, whether aligned with the liberal or conservative party, wields influence over administrative decisions. This influence extends to the use of illegal means to control the administration.[45][46] The leader's immunity from government intervention is derived from their status as the head of their local political party: "the law is applied for the benefit of the leader's supporters and to the disadvantage of their opponents."[47][48]

"The cacique distributes things that belong to the jurisdiction of the state, the provinces and the municipality, and he is distributed according to his whim. Positions in these administrations, permits to build or open businesses or exercise professions, reductions or exemptions from legal obligations of all kinds, added to the fact that, if he has the power to do all this, he also has the power to harm his enemies, and free his friends. In some cases, the cacique with a personal fortune may make concessions e his own nest egg, but normally what the cacique does is channel administrative favors. Caciquism, therefore, feeds on illegality [...]. The cacique must ensure that a whole range of administrative and judicial decisions important to the life or people of the locality are taken according to anti-legal criteria that convince him."

— Joaquín Romero Maura

Feliciano Montero characterizes the cacique as the intermediary between the central administration and the citizens, indicating that the entity yields influence beyond the electoral period, despite this being the most scandalous time. Montero posits that the cacique's impact maintains consistency within the political life of the country. Caciquism primarily represents the manifestation and logical expression of a social and political structure that persistently displays in the daily interpersonal interactions through patron-client relationships and political-administrative connections.[49] During the Restoration era, a judge described caciquism as "the personal regime exercised in the villages [pueblos] by twisting or corrupting the proper functions of the State through political influence, in order to subordinate them to the selfish interests of certain individuals or groups."[50] Consequently, the administration controlled the core of the caciquil system.[51] The liberal José Canalejas, in 1910, referred to a powerful cacique in Osuna, stating in a letter to the conservative Antonio Maura that the cacique had nothing aside from influence with various senior officials who disobeyed the government and gossiped abuses of all sorts.[52] In other words, the cacique is the local party leader who manipulates the administrative apparatus for his own benefit and that of his clients.[53]

Under the Restoration, political and electoral practices deviated from the legal standards. Reports frequently surfaced regarding the preparation of elections, which included the "encasillado" process. This entailed the Ministry of the Interior filling in constituencies' "boxes" with the names of government-preferred candidates who would receive protection. These candidates could be from either the ruling party, which obtained the decree to dissolve the Cortes and organized the elections to win a majority, or from the opposition. The encasillado was not solely a government directive but rather the outcome of bitter negotiations between multiple political factions. Indeed, within the same political party that controlled the Council of Ministers, various factions routinely coexisted, each represented by leaders of different clienteles who claimed a certain number of parliamentary seats based on their influence. The dissolution of the two dynastic parties under the reign of Alfonso XIII further multiplied the number of power brokers, thereby complicating the practice of "encasillado."

The caciques were part of a large informal hierarchical network. The local cacique answered to the district cacique, who then received instructions from the civil governor of the province.[1][54]

Following the encasillado event in Madrid, discussions continued on a local level through the designated representative of central power in each province, the civil governor. The governor aimed to reach an understanding with the caciques in their respective zones to enable the adjustment of results based on the ministry's wishes. The powerful local political figures, known as caciques, exerted significant influence over key positions such as town halls and courts. In many cases, they imposed their will on government representatives. Municipal councils and opposition judges frequently resigned in support of ministerial supporters, but those who refused to do so could have their functions suspended by the authorities. As carrying out these falsifications became more challenging, some political bosses went so far as to include deceased individuals from local cemeteries in their electoral rolls.

Occasionally, individuals nominated by established political parties would change parties between consecutive elections.[19] In the late 19th century, the cacique of Motril (Granada) made a statement at the local casino after learning the election results. This anecdote depicts the workings of caciquism and the seizure of power by the two dynastic parties.[55]

"We Liberals were convinced we would win the election. But God didn't want us to. - Long pause - From the looks of it, we Conservatives won the election."

The implementation of universal suffrage in 1890 did not democratize the system, instead it significantly increased Caciquist practices.[30][56]

The dynastic parties perpetuated this institutionalized corruption, refraining from comprehensive reform of the municipal system. Even though they criticized the system, they did not take action to amend it, despite the submission of 20 local government reform proposals between 1882 and 1923. The political groups excluded from the turno had the genuine political intention to stop the abuses of the networks of influence.[57] Nevertheless, while they succeeded in some districts, the effect on a national scale was too marginal. The groups excluded from the turno were first the conservatives, republicans and socialists of Silvela,[32] and then the Regionalist League of Catalonia.[58]

The end of caciquism: the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the Second Republic

[edit]From the 20th century onward, the system became increasingly fragile and relied exclusively on economically underdeveloped rural regions. In such areas, voter turnout is exceptionally high, implying significant vote manipulation. In contrast, major urban centers usually experienced low turnout and saw a marked decline of dynastic parties. These parties disappeared from the political landscape in Barcelona early in the century and later in Valencia.[59][60]

At times, there was a possibility that public opinion could shatter the oligarchic political circle, such as the instances when universal male suffrage was implemented in 1890, during the colonial crisis in 1898, or towards the end of the Restoration when the turno parties were disbanding. However, this did not come to fruition. The public's acceptance of Primo de Rivera's coup d'état in 1923 can be partially attributed to the sense of powerlessness felt by those seeking significant political change. The dictatorship's program emphasized the termination of "old politics" and the rejuvenation of the country as top priorities. The replacement of the "tiny politics" of the previous caciquil stage, which served only clientele, with "authentic politics" was among the declared aims of the regime. The dictator's actions were believed to be those of a messiah, expected to magically lift the state out of its lethargy. However, the measures taken against caciquism by the new regime were temporary. Municipal councils and deputations were suspended and given over to military authorities in each province, and later to government delegates appointed specifically for this purpose. In many cases, these delegates ended up replacing the caciques or facing opposition from them, making their regenerative efforts impossible.

The proclamation of the Republic in 1931 resulted in comprehensive participation of political currents previously excluded, including the Republican and Socialist parties. Additionally, fairer and more participatory electoral laws were introduced. In certain regions, the caciquist system faced an irreversible crisis. However, in other regions, this system remained resilient due to the enduring bonds of personal influence that underpinned its domination. Meanwhile, powerful traditional entities in the agrarian sphere started organizing themselves into political parties capable of competing under the new circumstances, in order to defend their interests. The emergence of new conservative political forces, exemplified by the agrarians, was a direct result of these changes. Other groups, such as radicalism, underwent significant processes of moderation. Additionally, the formation of important mass parties, such as the CEDA, marked a pivotal moment in political history.

Interpretations

[edit]According to British historian Raymond Carr, caciquism is a result of formally democratic institutions being imposed on an underdeveloped economy, an "anemic society" as described by José Ortega y Gasset. This was enabled by centralization of the Restoration system, where local administrations, municipal and provincial, were fully manipulated by the central power, as well as by politicization of the judiciary.[61] To maintain the functionality of this system, electoral conflicts were typically preceded by significant turnovers in local mayors and judges.[62]

As per the analysis by historian Pamela Radcliff, caciquism emerged as a modern mechanism of the liberal revolution that articulated the new state within the specific local/central dynamics of nineteenth-century Spain. Like pronunciamientos and military intervention, caciquism was another channel through which the liberal state functioned, not the main evidence of its failure.[63]

See also

[edit]- Cacique democracy – Term coined for the feudal political system of the Philippines

- Encasillado

References

[edit]- ^ a b c (ca) Caciquism in the Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana

- ^ "Caciquism" entry in Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "[...] the existence of caciquismo did not begin in regenerationist times, but it was then when it was coined as one of the various "evils of the fatherland" that afflicted intersecular Spain [...]. [...] this binomial [oligarchy and caciquismo] of Costa's, which has become the title of history books and manuals, continues to be, more than a century later, the most widely used to characterize the restorationist period. [...] The fact [...] of emphasizing oligarchy and caciquism exclusively in the period of the Restoration (1875-1923) has given rise in Spanish historiography to a compartmentalization into periods that makes it difficult to see lines of continuity in the essentials and hinders notably the understanding of the long trajectories. " (Romero Salvador 2021, p. 9, 21-22)

- ^ [...] we contrast terms that are not mutually exclusive. What is opposed to ''militarism'' are not ''oligarchy'' and ''caciquism'', but ''civilism'' [...]. A militarist regime can also be oligarchic and cacique. In fact, the Elizabethan regime [was] [...] cacique by practice, given that almost all of the twenty-two elections held were won by the party that called them. (Romero Salvador 2021, p. 24-25)

- ^ Tavares de Almeida 1991.

- ^ a b c d (fr) Juan pro (trans. from Spanish by Stéphane Michonneau), "Figure du cacique, figure du caudillo: les languages de la construction nationale en Espagne et en Argentine, 1808-1930", Genèses, no 62, 2006, pp. 27-48 (read online, accessed November 25, 2022)

- ^ a b (es) Lorenzo Meyer, "Los caciques: Ayer, hoy ¿y mañana?", Letras Libres, December 31, 2000 (read online, accessed December 8, 2022)

- ^ Lexicographical and etymological information on "cacique" in the Trésor de la langue française informatisé, on the Centre national de ressources textuelles et lexicales website.

- ^ (es) Joan Coromines, Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 17-32.

- ^ a b c Romero Salvador 2021, p. 18-19.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 17-18. "Situated in that hierarchically intermediate step between the lords and the components of the tribes, the caciques were, more than useful, obligatory for the conquering conquerors."

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 410.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 409-410.

- ^ a b Romero Salvador 2021, p. 19.

- ^ (es) "Cacicada" entry archive in the Diccionario de la lengua española, Real Academia Española.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 20.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 96-97.

- ^ a b Radcliff 2018, p. 146-147

- ^ Carr 2003, p. 353-354.

- ^ a b c Pérez 1996, p. 613

- ^ Radcliff 2018, p. 146 : "large businessmen or landowners could intimidate their employees at the time of casting the ballot, bureaucrats with connections in Madrid could get permission to build the desired road in exchange for votes, or local officials could fill the electoral roll with deceased individuals. All these mechanisms worked in part because there was no secret ballot, no confirmation of the voter's identity, and no independent control of the polling place."

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 98. "The patron/client relationship is not, in itself, a relationship of force, although there are undoubtedly a multitude of circumstances that force the client to place himself in the hands of the patron. The relationship is based on the idea of mutual benefit and the exclusion of others in the access to the resources managed by the clientelist system."

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 416-417.

- ^ a b Varela Ortega 2001, p. 465-466.

- ^ Often described as the "architect" of the Restoration's political system.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 24-25. "It was, precisely, a certain way of using electoral caciquismo during this [Elizabethan] period that strengthened militarism. With each of the parties -Moderado and Progresista- aspiring to monopolize power and knowing that whoever held it won the elections, the only option of the other party was, barred the way of the ballot box, that of a military pronouncement that would be triumphant, would take it to the Government and from there call elections that, unfailingly, it would win."

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 96-97. "Sagasta [in the Sexenio] was able to develop cacique practices with the same impunity that Posada Herrera had done before or that Romero Robledo would later develop."

- ^ "Explication de la carte: Alava: Urquijo, Albacete: Ochando, Alicante: Capdepón, Almería: Navarro Rodrigo, Ávila: Silvela. Badajoz: Gálvez Holguín (Leopoldo Gálvez Hoguín in Congreso archive). Baléares: Maura. Barcelone: Comillas. Burgos: Liniers. Cáceres: Camisón (Laureano García Camisón in Congreso archive). Cadix: Auñón. Canaries: León y Castillo. Castellón: Tetuán. Ciudad Real: Nieto. Cordoue: Vega Armijo. La Corogne: Linares Rivas. Cuenca: Romero Girón. Gérone: Llorens. Grenade: Aguilera. Guadalajara: Romanones. Guipuscoa: Sánchez Toca. Huelva: Monleón. Huesca: Castelar. Jaén: Almenas. León: Gullón. Lérida: Duque de Denia. Logroño: Salvador (Amós Salvador on the Diccionario Biográfico Español (DBE) archive, Miguel Salvador on the DBE archive). Lugo: Quiroga Ballesteros. Madrid: La bola de Gobernación. Malaga: Romero Robledo. Murcie: García Alix. Navarre: Mella. Ourense: Bugallal. Oviedo: Pidal. Palencia: Barrio y Mier. Pontevedra: Elduayen. Salamanque: Tamames. Santander: Eguillor. Ségovie: Oñate. Séville: Ramos Calderón. Soria: Viscount of the Asilos. Tarragone: Bosch and Fustegueras. Teruel: Castel. Tolède: Cordovés. Valencia: Jimeno. Valladolid: Gamazo. Biscaye: Martínez Rivas (José María Martínez de las Rivas on Auñamendi archive). Zamora: Requejo. Saragosse: Castilian."

- ^ a b Dardé 1996, p. 84.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 409.

- ^ a b Carr 2003, p. 358

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 501, 528.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 20-22.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 95.

- ^ Montero 1997, p. 62-64.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 95-96.

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 95; 97. "Patronage appears as a dominant mode of political organization in many Mediterranean countries, especially in Italy, Spain, North Africa and the Middle East, but we also find it in eighteenth-century England and nineteenth-century France".

- ^ a b c Carr 2001, p. 35.

- ^ a b Elizalde Pérez-Grueso and Buldain Jaca 2011, p. 386

- ^ Montero 1997, p. 64-65.

- ^ Martorell Linares and Juliá 2019, p. 128.

- ^ Carr 2003, p. 357.

- ^ Indirect tax on consumption (Carr 2003, p. 357).

- ^ Montero 1997, p. 64.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 410-411.

- ^ Romero Salvador 2021, p. 68.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 412.

- ^ Montero 1997, p. 60-61.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 413.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 426-429. "Money and violence, however great they were, were never a sufficient condition for power. The only necessary and sufficient condition common to all forms of caciquismo was the control of the administrative apparatus; the intervention and manipulation of the administration."

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 429.

- ^ Varela Ortega 2001, p. 429-430.

- ^ "[the cacique] was the man who could deliver the votes, whether it was for a single province, a large city or a small municipality. [...] there was a whole hierarchy of caciques, each with his zone of influence." (Carr 2001, p. 32).

- ^ (es) Paul Preston, La Guerra Civil Española: reacción, revolución y venganza, Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2011 (read online archive).

- ^ Suárez Cortina 2006, p. 130-131.

- ^ Carr 2003, p. 361.

- ^ Carr 2003, p. 362.

- ^ Carr 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Cucó 1979, p. 69.

- ^ "If Spain had possessed the independent judicial body of England or the sensible administrative law code of France, caciquismo would not have flourished." (Carr 2003, p. 359).

- ^ Carr 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Radcliff 2018, p. 98

Appendix

[edit]Related articles

[edit]- Clientelism

- Turno

- Paternalism

- Power (social and political)

- Symbolic power

- Opinion leadership

- Banana republic

- Social network

Bibliography

[edit]- (es) Raymond Carr (trans. from English), España: de la Restauración a la democracia: 1875~1980 ["Modern Spain 1875-1980"], Barcelone, Ariel, coll. "Ariel Historia", 2001, 7th ed., 266 p. ISBN 9-788434-465428.

- (es) Raymond Carr (trans. from English), España: 1808-1975, Barcelone, Ariel, coll. "Ariel Historia", 2003, 12th ed., 826 p. ISBN 84-344-6615-5.

- (es) Joaquín Costa, Oligarquía y caciquismo como la forma actual de gobierno en España: Urgencia y modo de cambiarla, 1901 (read online archive)

- (ca) Alfons Cucó, Sobre la ideologia blasquista: Un assaig d'aproximació, Valence, 3i4, July 1979, 111 p. ISBN 84-7502-001-1.

- (es) Carlos Dardé, La Restauración, 1875-1902: Alfonso XII y la regencia de María Cristina, Madrid, Historia 16, coll. "Temas de Hoy", 1996 ISBN 84-7679-317-0.

- (es) María D. Elizalde Pérez-Grueso and Blanca Buldain Jaca (dir.), Historia contemporánea de España: 1808-1923, Madrid, Akal, 2011 ISBN 978-84-460-3104-8, part IV, "La Restauración, 1875-1902", p. 371-521.

- (es) Miguel Martorell Linares and Santos Juliá, Manual de historia política y social de España (1808-2011), RBA, 2019, 544 p. ISBN 9788490562840.

- (es) Feliciano Montero, La Restauración. De la Regencia a Alfonso XIII, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1997, 1-188 p. ISBN 84-239-8959-3, "La Restauración (1875-1885)".

- (fr) Joseph Pérez, Histoire de l’Espagne, Paris, Fayard, 1996, 921 p. ISBN 978-2-213-03156-9.

- (es) Pamela Radcliff (trans. from English by Francisco García Lorenzana), La España contemporánea: Desde 1808 hasta nuestros días, Barcelone, Ariel, 2018, 1221 p. (ASIN B07FPVCYMS).

- Romero Salvador, Carmelo (2021). Caciques y caciquismo en España (1834-2020) (in Spanish). Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata. ISBN 978-8413522128.

- (es) Manuel Suárez Cortina, La España Liberal (1868-1917): Política y sociedad, Madrid, Síntesis, 2006 ISBN 84-9756-415-4.

- (pt) Pedro Tavares de Almeida, Eleições e caciquismo no Portugal oitocentista (1868-1890), Difel, 1991 ISBN 972-29-0248-2, read online archive).

- (es) José Varela Ortega (préf. Raymond Carr), Los amigos políticos: Partidos, elecciones y caciquismo en la restauración (1875-1900), Madrid, Marcial Pons / Junta de Castilla-León, coll. "Historia Estudios", 2001, 557 p. ISBN 84-7846-993-1.

External links

[edit]- Entries in general dictionaries and encyclopedias: Britannica archive Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa archive Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana archive