China–Pakistan Economic Corridor

| China–Pakistan Economic Corridor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statement | Securing Energy Import and Trade Boost for China,[1] Infrastructure Development for Pakistan[1] |

| Type of project | Economic corridor |

| Location | Pakistan: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit-Baltistan, Punjab, Balochistan, Sindh & Azad Kashmir China: Xinjiang |

| Established | 20 April 2015[2] |

| Budget | $62 billion[3] |

| Status | A few projects are operational, while Special Economic Zones are under construction (as of 2020).[5][6] |

| Website | http://cpec.gov.pk |

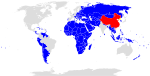

China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC; Chinese: 中巴经济走廊; pinyin: Zhōng bā jīngjì zǒuláng; Urdu: چین پاکستان اقتصادی راہداری) is a 3,000 km Chinese infrastructure network project currently under construction in Pakistan. This sea-and-land-based corridor aims to secure and shorten the route for China’s energy imports from the Middle East,[7] avoiding the existing path through the Straits of Malacca between Malaysia and Indonesia, which could be blockaded in case of war, thereby threatening China’s energy-dependent economy.[1][8][9] Developing a deep-water port at Gwadar in the Arabian Sea and establishing a robust road and rail network from this port to the Xinjiang region in western China would serve as a shortcut, enhancing trade between Europe and China.[1][8] In Pakistan, the project aims to address electricity shortages, develop infrastructure, and modernize transportation networks, while also transitioning the economy from an agriculture-based structure to an industrial one.[10]

CPEC is seen as the main plank of China's Belt and Road Initiative,[11] and as of early 2024, is the BRI's most developed land corridor. CPEC's potential impact on Pakistan has been compared to that of the Marshall Plan, undertaken by the United States in the post-war Europe.[12][13][14] Pakistani officials predict that CPEC will result in the creation of upwards of 2.3 million jobs between 2015 and 2030 and add 2 to 2.5 percentage points to the country's annual economic growth.[15] As of 2022, it has enhanced Pakistan's export and development capacity and provided 1/4th of its total electricity.[16]

It is also seen as addressing a national security issue for China by fostering economic development in the Xinjiang region, thus reducing militant influence on Muslim separatists among the native Uyghurs.[1][8][9][17] Following the proposal by Chinese President Li Keqiang in 2013,[7] the preliminary study on this project was completed in 2014, acknowledging the hostile environment and complicated geographic conditions but emphasizing the importance of having a China-run port near the Gulf of Oman, a vital route for oil tankers.[18] Once this corridor is operational, the existing 12,000 km journey for oil transportation to China will be reduced to just 2,395 km.[19] This is estimated to save China $2 billion per year.[20] China had already acquired control of Gwadar Port on 16 May 2013.[18] Originally valued at $46 billion, the value of CPEC projects was $62 billion as of 2020.[21] By 2022, Chinese investment in Pakistan had risen to $65 billion.[22] China refers to this project as the revival of the Silk Road.[23] CPEC envisages rapidly upgrading Pakistan's infrastructure and thereby strengthening its economy by constructing modern transportation networks, numerous energy projects, and special economic zones.[24][25][26][27]

The potential industries being set up in the CPEC special economic zones include food processing, cooking oil, ceramics, gems and jewelry, marble, minerals, agriculture machinery, iron and steel, motorbike assembling, electrical appliances, and automobiles.[28]

Since 2021, due to growing pressure on China for being the world's biggest polluter, it has shifted its focus from coal-based energy investments in Pakistan to renewables. This shift is intended to promote a "greener" image of CPEC.[29] In June 2022, the Karot Hydropower Project began commercial operations to provide cheap, clean electricity and aims to reduce 3.5 million metric tons of carbon emissions annually.[30]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Plans for a corridor stretching from the Chinese border to Pakistan's deepwater ports on the Arabian Sea date back to the 1950s and motivated the construction of the Karakoram Highway beginning in 1959.[31] Chinese interest in Pakistan's deep-water harbor at Gwadar was rekindled in 2002, leading to construction at Gwadar port, which was completed in 2006. Expansion of Gwadar Port then ceased due to political instability in Pakistan following the fall of General Pervez Musharraf and the subsequent conflict between the Pakistani state and Taliban militants.[32]

Since the early 1990s, the IMF has provided more than a dozen bailouts to Pakistan to save its dwindling economy, which has struggled for 22 of the past 30 years to meet the austerity measures demanded by the IMF. Nadeem-ul-Haque, a former IMF official and former deputy chairman of the Pakistani government's Planning Commission, wrote, "The pattern is always the same. With the Fund's blessing, the government goes on a shopping spree, taking out costly loans for expensive projects, thus building up even more debt and adding new inefficiencies. After a few years, another crisis ensues, and it is met by another IMF program."[33] The Pakistani establishment views Chinese loans as an alternative to IMF loans.[34]

Should the initial $46 billion worth of projects be implemented, their value would be roughly equivalent to all foreign direct investment in Pakistan since 1970,[35] and would be equal to 17% of Pakistan's 2015 gross domestic product.[36]

In 2013, then Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang decided to further enhance mutual connectivity.[37] A memorandum of understanding on cooperation for a long-term plan for the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor was signed by Xu Shao Shi and Shahid Amjad Chaudhry.[38]

In February 2014, Pakistani President Mamnoon Hussain visited China to discuss plans for an economic corridor in Pakistan.[39] Two months later, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif met with Premier Li Keqiang in China to discuss further plans,[40] resulting in the full scope of the project being devised under Sharif's tenure.[41] In November 2014, the Chinese government announced its intention to finance Chinese companies as part of its $45.6 billion energy and infrastructure projects in Pakistan as part of CPEC.

Although China and Pakistan signed the official MoUs in 2015, the first details of the long-term plan under CPEC were publicly disclosed in 2017 when a Pakistani media outlet revealed access to the original documents.[42]

Announcement of CPEC

[edit]Chinese President Xi Jinping described his "fate-changing visit" to Pakistan for signing the CPEC agreement by saying, "I feel as if I am going to visit the home of my brother,"[43] and claimed that the friendship between the two nations was "higher than mountains, deeper than oceans, and sweeter than honey."[1] China frequently uses terms like "iron brothers" and "all-weather friends" to describe its relationship with Pakistan.[44] On 20 April 2015, Pakistan and China signed an agreement to commence work on the $46 billion project, which is roughly 20% of Pakistan's annual GDP,[45] with approximately $28 billion worth of fast-tracked "Early Harvest" projects to be developed by the end of 2018.[46][47]

Under CPEC, a vast network of highways and railways will be built across Pakistan. The government estimates that inefficiencies stemming from Pakistan's largely dilapidated transportation network cause a loss of 3.55% of the country's annual GDP.[48] Modern transportation networks built under CPEC will link seaports in Gwadar and Karachi with northern Pakistan, as well as points further north in western China and Central Asia.[49] A 1,100-kilometre-long motorway will be built between the cities of Karachi and Lahore,[50] while the Karakoram Highway from Hasan Abdal to the Chinese border will be completely reconstructed and overhauled.[35] The currently stalled Karachi–Peshawar main railway line will also be upgraded to allow for train travel at up to 160 km per hour by December 2019.[51][52] Pakistan's railway network will also be extended to eventually connect to China's Southern Xinjiang Railway in Kashgar.[53] The estimated $11 billion required to modernize transportation networks will be financed by subsidized concessionary loans.[54]

Over $33 billion worth of energy infrastructure is set to be constructed by private consortia to help alleviate Pakistan's chronic energy shortages,[55] which regularly exceed 4,500 MW,[56] and have reduced Pakistan's annual GDP by an estimated 2–2.5%.[57] By the end of 2018, over 10,400 MW of generating capacity is expected to be brought online, with the majority developed as part of CPEC's fast-tracked "Early Harvest" projects.[58] A network of pipelines for transporting liquefied natural gas and oil will also be laid, including a $2.5 billion pipeline between Gwadar and Nawabshah to eventually transport gas from Iran.[59] Electricity from these projects will primarily be generated from fossil fuels, though hydroelectric and wind-power projects are also included, as well as the construction of one of the world's largest solar farms.[60]

Should the initial $46 billion worth of projects be implemented, their value would be roughly equivalent to all foreign direct investment in Pakistan since 1970,[35] and would represent 17% of Pakistan's 2015 gross domestic product.[36] CPEC is seen as a central component of China's Belt and Road Initiative.[11] At the start of the project, Pakistan assigned about 10,000 troops to protect Chinese investments,[9] a number that increased to 15,000 active troops by 2016.

Subsequent developments

[edit]On 12 August 2015, in the city of Karamay, China and Pakistan signed 20 additional agreements worth $1.6 billion to further expand the scale and scope of CPEC.[61] Details of the plan remain opaque,[62] but it is reported to mainly focus on increasing energy generation capacity.[63][better source needed] As part of the agreement, Pakistan and China have also agreed to cooperate in the field of space research.[64]

In September and October 2015, the United Kingdom announced two separate grants to Pakistan for the construction of roadways complementary to CPEC.[65][66] In November 2015, China incorporated CPEC into its 13th Five-Year Development Plan,[67] and in December 2015, China and Pakistan agreed on an additional $1.5 billion investment to establish an information and technology park as part of CPEC.[68] On 8 April 2016, during a visit by Xinjiang Communist Party Chief Zhang Chunxian, companies from Xinjiang signed $2 billion in additional agreements with their Pakistani counterparts, covering infrastructure, solar power, and logistics.[69]

The first convoy from China arrived in Gwadar on 13 November 2016, marking the formal commencement of CPEC operations.[70] On 2 December 2016, the first cargo train departed from Yunnan, launching the direct rail and sea freight service between China and Pakistan. The train, loaded with 500 tonnes of commodities, left Kunming for the port city of Guangzhou, where the cargo was transferred to ships for transport to Karachi, thereby opening the new route.[71] The new rail and sea freight service is expected to reduce logistics costs, including transportation, by 50 percent.[72]

In November 2016, China announced an additional $8.5 billion investment in Pakistan, with $4.5 billion allocated to upgrading Pakistan's main railway line from Karachi to Peshawar, including improvements to tracks, speed, and signaling, and $4 billion directed towards an LNG terminal and transmission lines to alleviate energy shortages.[73] In February 2017, the Egyptian Ambassador to Pakistan expressed interest in CPEC cooperation.[74] In January 2017, Chief Minister Pervez Khattak of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa stated that he had received assurances from Chinese investment companies of up to $20 billion in investments for various projects.[75] In March 2017, an agreement was signed for these projects, which include: a $1.5 billion oil refinery, $2 billion in irrigation projects, a $2 billion motorway between Chitral and DI Khan, and $7 billion in hydroelectric projects.[76]

As of September 2017, over $14 billion worth of projects were under construction.[11] In March 2018, Pakistan announced that once the ongoing energy projects were completed, future CPEC energy initiatives would focus on hydropower.[77]

In 2022, Federal Minister for Planning, Development, and Special Initiatives, Ahsan Iqbal, criticized the CPEC Authority for failing to attract investments and called for its dissolution.[78] On 17 August 2022, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif approved, in principle, the abolition of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Authority, pending China's consent.[79]

Projects in Gwadar

[edit]

Gwadar gained strategic importance after the Kargil War when Pakistan recognized the need for a military naval port, leading to the construction of the Karachi-Gwadar Coastal Highway for defense purposes.[80] Gwadar is central to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project, envisioned as the link between China's ambitious One Belt, One Road initiative and its 21st Century Maritime Silk Road project.[81] Over $1 billion worth of projects were planned around the port by December 2017.

As of 2022, only three CPEC projects in Gwadar were declared completed: the $4 million Gwadar Smart Port City Master Plan, the $300 million Physical Infrastructure of Gwadar Port and the Free Zone Phase-1, and the $10 million Pak-China Technical and Vocational Institute. Meanwhile, a dozen projects worth nearly $2 billion, including water supply, electricity provision, expressways, an international airport, a fishing harbor, and a hospital, remain undeveloped.[82]

Over the past two years, China has provided 7,000 solar panel sets to households in Gwadar. An additional 10,000 sets are being prepared for distribution to underprivileged communities in Balochistan. The Chinese Embassy in Pakistan is also set to donate household solar units and other forms of assistance to the people of Balochistan.[16]

Gwadar Port Complex

[edit]Initial infrastructure works at Gwadar Port commenced in 2002 and were completed in 2007,[32] however plans to upgrade and expand Gwadar's port stalled. Under the CPEC agreement, Gwadar Port will initially be expanded and upgraded to accommodate larger ships with a deadweight tonnage of up to 70,000.[83] Improvement plans also include the construction of a $130 million breakwater around the port,[84] as well as the construction of a floating liquefied natural gas facility that will have a capacity of 500 million cubic feet of liquefied natural gas per day and will be connected to the Gwadar-Nawabshah segment of the Iran–Pakistan gas pipeline.[85]

The expanded port is located near a 2,282-acre free trade area in Gwadar, which is being modeled on the lines of the Special Economic Zones of China.[86] The land was handed to the China Overseas Port Holding Company in November 2015 as part of a 43-year lease.[87] The site will include manufacturing zones, logistics hubs, warehouses, and display centers.[88] Businesses located in the zone will be exempt from customs authorities as well as many provincial and federal taxes.[83] Businesses established in the special economic zone will be exempt from Pakistani income, sales, and federal excise taxes for 23 years.[89] Contractors and subcontractors associated with China Overseas Port Holding Company will be exempt from such taxes for 20 years,[90] while a 40-year tax holiday will be granted for imports of equipment, materials, plant/machinery, appliances, and accessories that are used for the construction of Gwadar Port and the special economic zone.[91]

The special economic zone will be completed in three phases. By 2025, it is envisaged that manufacturing and processing industries will be developed, with further expansion of the zone intended to be completed by 2030.[32] On 10 April 2016, Zhang Baozhong, chairman of China Overseas Port Holding Company, said in a conversation with The Washington Post that his company planned to spend $4.5 billion on roads, power, hotels, and other infrastructure for the industrial zone, as well as other projects in Gwadar city.[15]

Gwadar city projects

[edit]China will grant Pakistan $230 million to construct a new international airport in Gwadar.[92] The provincial government of Balochistan has set aside 4,000 acres for the construction of the new $230 million Gwadar International Airport, which will require an estimated 30 months for completion.[93] The costs will be fully funded by grants from the Chinese government, which Pakistan will not be obliged to repay.[94]

The city of Gwadar is further being developed with the construction of a 300 MW coal power plant, a desalinization plant, and a new 300-bed hospital, which are to be completed in 2023.[95] Plans for Gwadar also include the construction of the Gwadar East Bay Expressway – a 19-kilometer controlled-access road that will connect Gwadar Port to the Makran Coastal Highway.[96] These additional projects are estimated to cost $800 million and will be financed by 0% interest loans extended by the Exim Bank of China to Pakistan.[95]

In addition to the aforementioned infrastructure works, the Pakistani government announced in September 2015 its intention to establish a training institute named Pak-China Technical and Vocational Institute at Gwadar.[32] This institute will be developed by the Gwadar Port Authority at a cost of 943 million rupees,[32] and is designed to impart the skills required to operate and work at the expanded Gwadar Port.[32]

As of 2017, there are a total of nine projects funded by China in and around Gwadar.[97]

Development of Gwadar includes the construction of a hospital funded by a Chinese government grant. The proposed project includes the building of medical blocks, nursing and paramedical institutes, a medical college, a central laboratory, and other allied facilities, along with the supply of medical equipment and machinery.[98]

In 2020, the government[which?] released funds of Rs 320 million for a Gwadar Seawater Desalination Plant with a capacity of five million gallons per day. The funds were also allocated for expanding the optical fiber network in Gwadar,[99] and for the construction of a fish landing jetty.[100]

Roadway projects

[edit]

The CPEC project includes significant upgrades and overhauls to Pakistan's transportation infrastructure. So far, China has announced financing for $10.63 billion worth of transportation infrastructure under the CPEC project; $6.1 billion has been allocated for constructing "Early Harvest" roadway projects at an interest rate of 1.6 percent.[101] The remaining funds will be allocated when the Pakistani government awards contracts for road segments that are still in the planning phase.

Three corridors have been identified for cargo transport: the Eastern Alignment through the heavily populated provinces of Sindh and Punjab, where most industries are located; the Western Alignment through the less developed and more sparsely populated provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan; and the future Central Alignment, which will pass through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Balochistan.[102]

Karakoram Highway

[edit]

The CPEC projects involve reconstruction and upgrades to National Highway 35 (N-35), which forms the Pakistani section of the Karakoram Highway (KKH). The KKH spans the 887 kilometers between the China-Pakistan border and the town of Burhan, near Hasan Abdal. At Burhan, the existing M1 motorway will intersect the N-35 at the Shah Maqsood Interchange. From there, access to Islamabad and Lahore continues via the M1 and M2 motorways. Burhan will also be at the intersection of the Eastern Alignment and Western Alignment.

Upgrades to the 487-kilometer section between Burhan and Raikot are officially known as the Karakoram Highway Phase 2 project. At the southern end of the N-35, construction is underway for a 59-kilometer, 4-lane controlled-access highway between Burhan and Havelian, which will be officially named the E-35 expressway.[103] North of Havelian, the next 66 kilometers will be upgraded to a 4-lane dual carriageway between Havelian and Shinkiari.[104] Groundbreaking for this portion commenced in April 2016.[105]

The entire 354 kilometers of roadway north of Shinkiari, extending to Raikot near Chilas, will be constructed as a 2-lane highway.[105] Construction on the first section between Shinkiari and Thakot began in April 2016, alongside the construction of the Havelian to Shinkiari 4-lane dual carriageway further south.[106] Both sections are expected to be completed within 42 months at a cost of approximately $1.26 billion, with 90% of the funding provided by China's EXIM Bank in the form of low-interest concessional loans.[106][107][108]

Between Thakot and Raikot lies an area where the Pakistani government is either planning or actively constructing several hydropower projects, including the Diamer-Bhasha Dam and Dasu Dam. Sections of the N-35 around these projects will be completely rebuilt in conjunction with the dam construction.[109] In the meantime, this section of the N-35 is being upgraded from its current state until dam construction fully begins. Improvement projects on this section are expected to be completed by January 2017 at a cost of approximately $72 million.[110][111] The next 335 kilometres of roadway connect Raikot to the China-Pakistan border. Reconstruction of this section of the roadway began before the CPEC initiative, following significant damage from the 2010 Pakistan floods. Most of the reconstruction was completed by September 2012 at a cost of $510 million.[112]

In 2010, a large earthquake struck the region near the China-Pakistan border, triggering massive landslides that dammed the Indus River and led to the formation of Attabad Lake. Portions of the Karakoram Highway were submerged by the lake, forcing all vehicular traffic onto barges to cross the newly formed reservoir. Construction on a 24-kilometer series of bridges and tunnels around Attabad Lake began in 2012 and took 36 months to complete. The bypass, consisting of two large bridges and five kilometers of tunnels, was opened to the public on 14 September 2015 at a cost of $275 million.[113][114] Additionally, the 175-kilometer road between Gilgit and Skardu will be upgraded to a 4-lane road at a cost of $475 million to provide direct access to Skardu from the N-35.[115][116]

Eastern alignment

[edit]The term "Eastern Alignment" of CPEC refers to roadway projects located in the provinces of Sindh and Punjab, some of which were first envisioned in 1991.[117] As part of the Eastern Alignment, a 1,152-kilometer-long motorway will connect Pakistan's two largest cities, Karachi and Lahore, with a 6-lane controlled access highway designed for travel speeds of up to 120 kilometers per hour.[118] The entire project will cost approximately $6.6 billion, with the bulk of financing provided by various Chinese state-owned banks.[119]

The entire Eastern Alignment motorway project is divided into four sections: a 136-kilometer-long section between Karachi and Hyderabad, also known as the M9 motorway; a 345-kilometer-long section between Hyderabad and Sukkur; a 392-kilometer-long section between Sukkur and Multan;[120] and a 333-kilometer section between Multan and Lahore via the town of Abdul Hakeem.[121]

The first section of the project provides high-speed road access from the Port of Karachi to the city of Hyderabad and interior Sindh. Upgrade and construction work on this section, currently known as the Super Highway between Karachi and Hyderabad, began in March 2015 and aimed to convert the road into the 6-lane controlled access M9 Motorway, which was completed in approximately 30 months.[122] In February 2017, a completed 75-kilometer stretch of the motorway was opened for public use by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.[123]

At the terminus of the M9 motorway in Hyderabad, the Karachi-Lahore Motorway will continue to Sukkur as a six-lane controlled-access motorway, also known as the M6 motorway. This section will be 345 kilometers long[120] and is projected to cost $1.7 billion.[124] It will provide high-speed road access to interior Sindh, particularly near the towns of Matiari, Nawabshah, and Khairpur. The project will require the construction of seven interchanges and 25 bridges over the Indus River and irrigation canals.[125] The planned route of the motorway runs roughly parallel to the existing National Highway and Indus Highway in various sections. In July 2016, the Pakistani government announced that the project would be open to international bidders on a build-operate-transfer basis, with Chinese and South Korean companies expressing interest in the project.[124]

The 392-kilometer Sukkur to Multan section of the motorway is estimated to cost $2.89 billion.[118] Construction on this section began on 6 May 2016 and was completed in September 2019.[126] The road is a six-lane controlled-access highway[127] featuring 11 interchanges, 10 rest facilities, 492 underpasses, and 54 bridges along its route.[126] In January 2016, the Pakistani government awarded the construction contract to China State Construction Engineering.[118] However, final approvals for the disbursement of funds from the Government of the People's Republic of China were not granted until May 2016.[108][118] Ninety percent of the project's cost is being financed through concessionary loans from China, with the remaining 10% funded by the Government of Pakistan.[128] The construction of this segment is expected to take 36 months.[118]

Construction of the section between Multan and Lahore, costing approximately $1.5 billion,[129] was launched in November 2015.[130] The project is a joint venture between the China Railway Construction Corporation Limited and Pakistan's Zahir Khan and Brothers Engineers.[131] The total length of this motorway section is 333 kilometers; however, the first 102 kilometers of the road between Khanewal and Abdul Hakeem is part of the M4 Motorway and is being funded by the Asian Development Bank.[132][133] The remaining 231 kilometers between Abdul Hakeem and Lahore, currently under construction as part of CPEC, will complete this section of the motorway.[134]

Western alignment

[edit]

The CPEC project plans to expand and upgrade the road network in the Pakistani provinces of Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and western Punjab Province as part of the Western Alignment. This project will upgrade several hundred kilometers of road into 2 and 4-lane divided highways by mid-2018, with land acquisition allowing for future upgrades to a 6-lane motorway.[135] The CPEC project includes the reconstruction of 870 kilometers of road in Balochistan province alone, of which 620 kilometers had already been rebuilt by January 2016.[136]

The Western Alignment roadway network will start at the Barahma Bahtar Interchange on the M1 Motorway near the towns of Burhan and Hasan Abdal in northern Punjab province.[137] The newly reconstructed Karakoram Highway will connect to the Western Alignment at Burhan, where the new 285-kilometer controlled-access Brahma Bahtar-Yarik Motorway will begin.[138] The motorway will terminate near the town of Yarik, just north of Dera Ismail Khan.[139] Groundbreaking for the project occurred on 17 May 2016, and it was inaugurated on 5 January 2022.[140] The motorway crosses the Sindh Sagar Doab region and the Indus River at Mianwali before entering Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. It includes 11 interchanges, 74 culverts, and 3 major bridges over the Indus, Soan, and Kurram Rivers.[141] The total cost of the project was approximately $1.05 billion.[142]

At the southern terminus of the new Brahma Bahtar-Yarik Motorway, the N-50 National Highway will be upgraded between Dera Ismail Khan in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Zhob in Balochistan province, with future plans for reconstruction between Zhob and Quetta.[143] The upgraded road will be a 4-lane dual-carriageway spanning the 205-kilometer distance between the two cities.[144] The first portion of the N-50 to be upgraded is the 81-kilometer section between Zhob and Mughal Kot, with construction beginning in January 2016.[145] This segment is expected to be completed by 2018 at a cost of $86 million.[143] Although the project is a key component of CPEC's Western Alignment,[145] its financing will come from the Asian Development Bank under a 2014 agreement predating CPEC,[146][147] and from a grant provided by the United Kingdom's Department for International Development.[148]

Heading south from Quetta, the Western Alignment of CPEC continues to the town of Surab in central Balochistan via the N-25 National Highway. From Surab, the N-85 National Highway extends 470 kilometers to connect central Balochistan with the town of Hoshab in southwestern Balochistan near the city of Turbat. This segment of the road was completed on schedule in December 2016.[149][150]

Along the Western Alignment route, the towns of Hoshab and Gwadar are connected by a newly built 193-kilometer section of the M8 Motorway. This portion, linking Hoshab to Gwadar, was completed and inaugurated in February 2016 by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.[151]

The Western Alignment will feature special economic zones along its route,[152] with at least seven planned in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.[135]

Central alignment

[edit]Long-term plans for a "Central Alignment" of CPEC include a network of roads that represents the shortest route of CPEC. It will start in Gwadar and travel upcountry through Basima, Khuzdar, Sukkur, Rajanpur, Layyah, Muzaffargarh, and Talagang, with onward connections to the Karakoram Highway via the Brahma Bahtar–Yarik Motorway.[153]

Associated roadway projects

[edit]- ADB funded projects

The 184-kilometer-long M-4 Motorway between Faisalabad and Multan does not fall under CPEC projects but is considered vital to the CPEC transportation network. It will be financed by the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank,[132] marking the first project jointly financed by these banks.[154] Additionally, the government of the United Kingdom announced a $90.7 million grant in October 2015 for the construction of a portion of the M4 Motorway project.[155]

The Karakoram Highway south of Mansehra will be upgraded to a controlled-access highway and officially known as the E-35 expressway. Although crucial for the route between Gwadar and China, the E35 will not be financed by CPEC funds. Instead, it will be funded by the Asian Development Bank[156] and a $121.6 million grant from the United Kingdom.[157] Once completed, the E35 Expressway, M4 Motorway, and Karachi-Lahore Motorway will provide continuous high-speed road travel on controlled-access motorways from Mansehra to Karachi, a distance of 1,550 kilometers.

Approximately halfway between Zhob and Quetta, the town of Qilla Saifullah in Balochistan is located at the intersection of the N50 National Highway and the N70 National Highway. The two roads form a 447-kilometer route between Quetta and Multan in southern Punjab. Although the N70 project is not officially part of CPEC, it will connect the CPEC Western Alignment to the Karachi-Lahore Motorway at Multan. Reconstruction of the 126-kilometer section of the N70 between Qilla Saifullah and Wagum is scheduled for completion by 2018,[158] and is financed by a $195 million package from the Asian Development Bank,[147] and a $72.4 million grant from the United Kingdom's Department for International Development.[148]

Railway projects

[edit]

The CPEC project emphasizes major upgrades to Pakistan's aging railway system, including the reconstruction of the entire Main Line 1 railway between Karachi and Peshawar by 2020.[159] This railway currently handles 70% of Pakistan Railways traffic.[160] As of 25 May 2022, the project is stalled due to China's reluctance to provide funds.[161] In addition to the stalled Main Line 1 railway, upgrades and expansions are planned for Main Line 2 and Main Line 3. The CPEC plan also includes completing a rail link over the 4,693-meter high Khunjerab Pass, providing direct access for Chinese and East Asian goods to Pakistani seaports at Karachi and Gwadar by 2030.[160]

The procurement of 250 new passenger coaches and the reconstruction of 21 train stations are also planned as part of the first phase of the project, bringing the total investment in Pakistan's railway system to approximately $5 billion by the end of 2019.[162] Of these, 180 coaches are to be built at the Pakistan Railways Carriage Factory near Islamabad,[163] while the Government of Pakistan intends to procure an additional 800 coaches at a later date, with the goal of building 595 of those coaches in Pakistan.[163]

In September 2018, the new government led by Prime Minister Imran Khan reduced Chinese investment in the railways by $2 billion to $6.2 billion due to financing burdens.[164]

Main Line 1

[edit]The CPEC "Early Harvest" plan includes[citation needed] a complete overhaul of the 1,687-kilometer-long Main Line 1 railway (ML-1) between Karachi and Peshawar. The plan was initially floated in 2015;[165] however, as of January 2023, construction on the project has not yet started, with funding only secured in November 2022.[166] The total cost of the project is estimated to be US$8.2 billion.[167]

The upgrade plan involves doubling the track from Karachi to Peshawar, providing grade separation and implementing communications-based train control;[168] these improvements will increase capacity and allow for faster trains on the line.[169]

Main Line 2

[edit]

In addition to upgrading the ML-1, the CPEC project also calls for a similar major upgrade of the 1,254-kilometer-long Main Line 2 (ML-2) railway between Kotri in Sindh province and Attock in northern Punjab province via the cities of Larkana and Dera Ghazi Khan.[170] The route towards northern Pakistan roughly parallels the Indus River, unlike the ML-1, which takes a more eastward course towards Lahore. The project also includes a plan to connect Gwadar to the town of Jacobabad, Sindh,[171] which lies at the intersection of the ML-2 and ML-3 railways.

Main Line 3

[edit]Medium-term plans for the Main Line 3 (ML-3) railway include the construction of a 560-kilometer railway line between Bostan near Quetta and Kotla Jam in Bhakkar District near Dera Ismail Khan.[172] This line will provide access to southern Afghanistan. The route will pass through Quetta and Zhob before terminating in Kotla Jam, with construction expected to be completed by 2025.[160]

Khunjerab Railway

[edit]

Longer-term projects under CPEC also call for the construction of the 682-kilometer-long Khunjerab Railway line between the city of Havelian and the Khunjerab Pass on the Chinese border,[172] with an extension to China's Lanxin Railway in Kashgar, Xinjiang. The railway will roughly parallel the Karakoram Highway and is expected to be completed by 2030.[160]

The cost of the entire project is estimated to be approximately $12 billion and will require 5 years for completion. A 300 million rupee study to establish the final feasibility of constructing the rail line between Havelian and the Chinese border is already underway.[173] A preliminary feasibility study was completed in 2008 by the Austrian engineering firm TBAC.[174]

Lahore Metro

[edit]The Orange Line of the Lahore Metro is a significant commercial project under CPEC.[175] This $1.6 billion project was initially planned for completion by Winter 2017. However, it faced several delays and was finally launched on 25 October 2020. The Orange Line spans 27.1 kilometers (16.8 mi), with 25.4 kilometers (15.8 mi) being elevated and the remaining portion underground between Jain Mandir and Lakshmi Chowk. The project has the capacity to transport 250,000 commuters per day, with plans to increase this to 500,000 commuters per day by 2025. As of now, the Orange Line of the Lahore Metro is fully operational.[176] It is the first automated rapid transit line in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan, and the first driverless metro in Pakistan. It is operated by the Punjab Mass Transit Authority and forms part of the Lahore Metro system.

Energy sector projects

[edit]Pakistan's current energy generating capacity is 24,830 MW.[177] Energy generation will be a major focus of the CPEC project, with approximately $33 billion expected to be invested in this sector.[55] An estimated 10,400 MW of electricity are slated for generation by March 2018 as part of CPEC's "Early Harvest" projects.[58]

The energy projects under CPEC will be constructed by private Independent Power Producers, rather than by the governments of China or Pakistan.[178] The Exim Bank of China will finance these private investments at 5–6% interest rates, while the government of Pakistan will be contractually obliged to purchase electricity from these firms at pre-negotiated rates.[179] In April 2020, hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, Pakistan asked China to ease repayment terms on $30 billion worth of power projects.[180][181]

Renewable-energy

[edit]In March 2018, Pakistan announced that hydropower projects would be prioritized following the completion of under-construction power plants.[77] Pakistan aims to produce 25% of its electricity requirements from renewable energy sources by 2030.[182] China's Zonergy company is expected to complete the construction of the world's largest solar power plant – the 6,500-acre Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park near Bahawalpur, with an estimated capacity of 1,000 MW, by December 2016.[183][184] The first phase of the project, completed by Xinjiang SunOasis, has a generating capacity of 100 MW.[185] The remaining 900 MW capacity will be installed by Zonergy under CPEC.[185]

The Jhimpir Wind Power Plant, built by the Turkish company Zorlu Enerji, has already begun to sell 56.4 MW of electricity to the government of Pakistan.[186] Under CPEC, another 250 MW of electricity are to be produced by the Chinese-Pakistan consortium United Energy Pakistan and others at a cost of $659 million.[187][188] Another wind farm, the Dawood Wind Power Project, is under development by HydroChina at a cost of $115 million and will generate 50 MW of electricity by August 2016.[189]

SK Hydro Consortium is constructing the 870 MW Suki Kinari Hydropower Project in the Kaghan Valley of Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province at a cost of $1.8 billion,[190] with financing from China's EXIM Bank.[191] The $1.5 billion Azad Pattan Hydropower Project, being developed on the River Jhelum, is sponsored by Gezhouba Group. With a generation capacity of 700.7 MW, the project will have the lowest generation tariff out of five proposed projects on the River Jhelum Cascade.[192]

The Karot Hydropower Project was financed by China's Silk Road Fund.[193]: 221 It was the fund's first project and part of its focus on supporting clean energy in Pakistan as one of the priority focuses of the corridor.[193]: 221–222

Pakistan and China have also discussed including the 4,500 MW, $14 billion Diamer-Bhasha Dam as part of the CPEC project,[194] though as of December 2015, no firm decision has been made, although Pakistani officials remain optimistic about its eventual inclusion.[195] On 14 November 2017, Pakistan dropped its bid to have the Diamer-Bhasha Dam financed under the CPEC framework.[196]

The $2.4 billion, 1,100 MW Kohala Hydropower Project, being constructed by China's Three Gorges Corporation, predates the announcement of CPEC, though funding for the project will now come from CPEC funds.[197] The project was approved by the government of Pakistani-administered Kashmir, the Chinese government, and the Three Gorges Corporation in 2020,[198] which was protested by India, which claims Kashmir as its territory.[199] Renewable energy projects also include a 640 MW Mahl hydropower project.[200]

Coal

[edit]Despite several renewable energy projects, the bulk of new energy generation capacity under CPEC will come from coal-based plants, with $5.8 billion worth of coal power projects expected to be completed by early 2019 as part of CPEC's "Early Harvest" projects.

On 26 May, it was announced that a 660 kV transmission line would be laid between Matiari and Lahore. The electricity would be produced from coal-based power plants at Thar, Port Qasim, and Hub. The line will have the capacity to supply 2,000 MW, with a 10 percent overload capability for 2 hours.[201]

- Balochistan

In Balochistan province, a $970 million coal power plant at Hub, near Karachi, with a capacity of 660 MW is being built by a joint consortium of China's China Power Investment Corporation and the Pakistani firm Hub Power Company. This is part of a larger $2 billion project to produce 1,320 MW from coal.[202]

A 300 MW coal power plant is also being developed in Gwadar and is financed by a 0% interest loan.[95] The development of Gwadar also includes a 132 kV (AIS) Grid Station along with an associated D/C Transmission line at Downtown Gwadar, as well as other 132 kV Sub Stations at Deep Sea Port Gwadar.[203]

- Punjab

The $1.8 billion Sahiwal Coal Power Project, which has been in full operation since 3 July 2017,[204] is located in central Punjab and has a capacity of 1,320 MW. It was built by a joint venture of two Chinese firms: Huaneng Shandong and Shandong Ruyi, who jointly own and operate the plant.[205] Pakistan will purchase electricity from the consortium at a tariff of 8.36 US cents/kWh.[206]

The $589 million project to establish a coal mine and a 300 MW coal power plant in the town of Pind Dadan Khan, located in Punjab's Salt Range, is being developed by China Machinery Engineering Corporation.[207] Pakistan's NEPRA has faced criticism for considering a relatively high tariff of 11.57 US cents/kWh proposed by the Chinese firm,[208] which was initially set at 8.25 US cents/kWh in 2014.[209] The Chinese firm claimed that the increase in coal transportation costs was due to the nonavailability of coal from nearby mines, which had initially been considered the primary source for the project. The company argued that coal would need to be transported from the distant Sindh province, resulting in a 30.5% increase in fuel costs due to inefficiencies in mining procedures.[210]

- Sindh

The Shanghai Electric company of China will construct two 660 MW power plants as part of the "Thar-I" project in the Thar coalfield of Sindh province. The "Thar-II" project will be developed by a separate consortium.[211][212] The facility will be powered by locally sourced coal,[213] and is expected to begin commercial operation in 2018.[214] Pakistan's National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) has agreed to purchase electricity from both Thar-I and Thar-II at a tariff of 8.50 US cents/kWh for the first 330 MW of electricity, 8.33 US cents/kWh for the next 660 MW, and 7.99 US cents/kWh for the subsequent 1,099 MW as further phases are developed.[215][216]

Near the Thar-I Project, the China Machinery Engineering Corporation and Pakistan's Engro Corporation will construct two 330 MW power plants as part of the "Thar-II Project". Initially, they had proposed constructing two 660 MW power plants. They will also develop a coal mine capable of producing up to 3.8 million tons of coal per year as part of the project's first phase.[217][better source needed] The first phase is expected to be completed by early 2019,[218] at a cost of $1.95 billion.[219] Subsequent phases are expected to generate an additional 3,960 MW of electricity over ten years.[212] As part of the infrastructure required for electricity distribution from the Thar I and II Projects, the $2.1 billion Matiari to Lahore Transmission Line and $1.5 billion Matiari to Faisalabad transmission line are also planned as part of the CPEC project.[58]

The 1,320 MW, $2.08 billion Port Qasim Power Project near Port Qasim will be a joint venture between Al-Mirqab Capital from Qatar and China's Power Construction Corporation – a subsidiary of Sinohydro Resources Limited.[220][221] Pakistan's NEPRA and SinoHydro agreed to set the levelized tariff for electricity purchased from the consortium at 8.12 US cents/kWh.[222] The first 660 MW reactor was commissioned in November 2017.[223]

Liquified natural gas

[edit]Liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects are also considered vital to CPEC. The Chinese government has announced its intention to build a $2.5 billion, 711-kilometre gas pipeline from Gwadar to Nawabshah in the province as part of CPEC.[224] The pipeline is designed to be part of the 2,775-kilometre-long Iran–Pakistan gas pipeline, with the 80-kilometre portion between Gwadar and the Iranian border to be connected once sanctions against Tehran are eased. Iran has already completed a 900-kilometre portion of the pipeline on its side of the border.[59]

The Pakistani portion of the pipeline is to be constructed by the state-owned China Petroleum Pipeline Bureau.[225] It will be 42 inches (1.1 metres) in diameter and have the capacity to transport 1×109 cubic feet (2.8×107 m3) of liquefied natural gas per day, with an additional 500×106 cubic feet (1.4×107 m3) capacity when the planned offshore LNG terminal is completed.[226] The project will not only provide gas exporters with access to the Pakistani market but will also allow China to secure a route for its own imports.[227]

The project should not be confused with the $2 billion, 1,100-kilometre North-South Pipeline liquefied natural gas pipeline, which is being constructed with Russian assistance between Karachi and Lahore, and is anticipated to be completed by 2018.[228] Nor should it be confused with the planned $7.5 billion TAPI Pipeline, a project involving Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

Other LNG projects, currently under construction with Chinese assistance and financing, will augment the scope of CPEC but are neither funded by nor officially considered a part of it. The 1,223 MW Balloki Power Plant, under construction near Kasur, is being built by China's Harbin Electric Company with financing from China's EXIM Bank. In October 2015, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also inaugurated the construction of the 1,180 MW Bhikhi Power Plant near Sheikhupura.[229] This plant is being jointly constructed by China's Harbin Electric Company and General Electric from the United States.[230] It is expected to be Pakistan's most efficient power plant and will provide enough power for an estimated 6 million homes.[230] The facility became operational in May 2018.[231]

"Early Harvest" projects

[edit]As part of the "Early Harvest" scheme of CPEC, over 10,000 megawatts of electricity-generating capacity is to be developed between 2018 and 2020.[58] While some "Early Harvest" projects will not be completed until 2020, the government of Pakistan plans to add approximately 10,000 MW of energy-generating capacity to Pakistan's electric grid by 2018 through the completion of projects that complement CPEC.

Although not officially under the scope of CPEC, the 1,223 MW Balloki Power Plant and the 1,180 MW Bhikki power plant were both completed in mid-2018.[231][232][229][233] Along with the 969 MW Neelum–Jhelum Hydropower Plant, completed in summer 2018, and the 1,410 MW Tarbela IV Extension Project, completed in February 2018,[234] this will result in an additional 10,000 MW being added to Pakistan's electricity grid by the end of 2018 through a combination of CPEC and non-CPEC projects.[235] A further 1,000 MW of electricity will be imported to Pakistan from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan as part of the CASA-1000 project, which is expected to be launched in 2018.[236]

Table of projects

[edit]| "Early Harvest" Energy Project[237] | Capacity | Location | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan Port Qasim Power Project. | 1,320 MW (2 x 660 MW plants) | Sindh | Operational |

| Thar-l Project | 1,320 MW (4 x 330 MW plants) | Sindh | Operational |

| Thar-ll Project and coal mine | 1,320 MW (2 x 660 MW plants) | Sindh | Operational |

| Sahiwal Coal Power Project | 1,320 MW (2 x 660 MW plants) | Punjab | Operational |

| Rahimyar Khan coal power project | 1,320 MW (2 x 660 MW plants) | Punjab | Operational |

| Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park | 1,000 MW | Punjab | Operational |

| Suki Kinari Hydropower Project | 870 MW (expected completion in 2020)[238] | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Operational |

| Karot Hydropower Project | 720 MW[239][240] | Punjab | Operational |

| China Power Hub Generation Company | 2X660 MW | Balochistan | Operational |

| Thar Engro Coal Power Project | 660 MW (2 x 330 MW plants) | Sindh | Operational |

| Gwadar coal power project | 300 MW | Balochistan | Operational |

| UEP Windfarm | 100 MW | Sindh | Operational |

| Dawood wind power project | 50 MW | Sindh | Operational |

| Sachal Windfarm | 50 MW | Sindh | Operational |

| Sunnec Windfarm | 50 MW | Sindh | Operational |

| Matiari to Lahore Transmission Line | 660 kilovolt | Sindh and Punjab | Operational |

Other areas of cooperation

[edit]The CPEC announcement encompassed not only infrastructure projects but also areas of cooperation between China and Pakistan.

Agriculture and aquaculture

[edit]CPEC includes provisions for cooperation in water resource management, livestock, and other agricultural fields. The plan encompasses projects such as agricultural information systems, storage and distribution of agricultural equipment, mechanization, demonstration and machinery leasing, and fertilizer production. Specifically, it aims to produce 800,000 tons of fertilizer and 100,000 tons of bio-organic fertilizer.[241][242] The framework also includes cooperation in remote sensing (RS) and geographical information systems (GIS), food processing, pre-and post-harvest handling and storage of agricultural produce, and the selection and breeding of new animal breeds and plant varieties, including fisheries and aquaculture.[243]

Science and technology

[edit]As part of CPEC, the two countries signed an Economic and Technical Cooperation Agreement,[244] and pledged to establish the China-Pakistan Joint Cotton Bio-Tech Laboratory.[244] They also committed to creating the China-Pakistan Joint Marine Research Center in collaboration with the State Oceanic Administration and Pakistan's Ministry of Science and Technology.[244] Additionally, Pakistan and China have agreed to cooperate in the field of space research.[64]

In February 2016, the two countries agreed to establish the Pak-China Science, Technology, Commerce and Logistic Park near Islamabad at an estimated cost of $1.5 billion.[245] The park will be situated on 500 hectares, which will be provided by Pakistan to China's Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, with all investments expected to come from the Chinese side over the course of ten years.[245]

In May 2016, construction began on the $44 million 820-kilometer-long Pakistan-China Fiber Optic Project, a cross-border Optical Fiber cable that will enhance telecommunication and the ICT industry in the Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Punjab regions, while offering Pakistan a fifth route for transmitting telecommunication traffic.[246][247] It will be extended to Gwadar.[248][249][99]

In May 2019, the Vice Presidents of China and Pakistan decided to launch a Huawei Technical Support Center in Pakistan.[201]

CPEC includes the establishment of a pilot project for Digital Terrestrial Multimedia Broadcast for Pakistan Television Corporation through a Chinese grant at the Rebroadcast Station (RBS) in Murree.[250] ZTE Corporation will collaborate with Pakistan Television Corporation on research and development of digital terrestrial television technologies, staff training, and content creation. This collaboration will include partnerships with Chinese multinational companies in various areas, including television sets and set-top boxes, as part of international cooperation.[251]

Other fields

[edit]The two nations also pledged cooperation in areas ranging from anti-narcotic efforts, to initiatives aimed at reducing climate change. Additionally, they agreed to enhance cooperation between their banking sectors and to establish closer ties between China Central Television and Pakistan Television Corporation.[244]

A Confucius Institute at the University of Punjab is planned to be launched in 2019. Moreover, the Rashakai Special Economic Zone on the M1 Highway, near Nowshehra, is also planned.[201]

Finance

[edit]Concessionary loans

[edit]Approximately $11 billion worth of infrastructure projects being developed by the Pakistani government will be financed at an interest rate of 1.6%,[84] after Pakistan successfully lobbied the Chinese government to reduce the rate from an initial 3%.[252] Loans will be dispersed by the Exim Bank of China, China Development Bank, and ICBC.[253] For comparison, loans for previous Pakistani infrastructure projects financed by the World Bank carried interest rates between 5% and 8.5%,[254] while interest rates on market loans approach 12%.[255]

The loan money will be used to finance projects planned and executed by the Pakistani government. Portions of the approximately $6.6 billion Karachi–Lahore Motorway are already under construction.[119][256] The $2.9 billion phase, which will connect Multan to Sukkur over a distance of 392 kilometers, has also been approved,[257] with 90% of costs financed by the Chinese government at concessionary interest rates, while the remaining 10% will be financed by the Public Sector Development Programme of the Pakistani government.[258] In May 2016, the $2.9 billion loan received final approvals from the Government of the People's Republic of China on 4 May 2016, and will be provided as concessionary loans with an interest rate of 2.0%.[108] The National Highway Authority of Pakistan reported that contractors arrived on site soon after the loan received final approval.[108]

The China Development Bank will finance $920 million for the reconstruction of the 487-kilometer portion of the Karakoram Highway between Burhan and Raikot.[259][260] An additional $1.26 billion will be lent by the China Exim Bank for the construction of the Havelian to Thakot portion of this 487-kilometer stretch of roadway,[106][107] to be dispersed as low-interest rate concessionary loans.[108]

$7 billion of the planned $8.2 billion overhaul of the Main Line 1 railway is to be financed by concessionary loans extended by China's state-owned banks.[261]

The long-planned 27.1 km $1.6 billion Orange Line of the Lahore Metro is regarded as a commercial project,[244] and does not qualify for the Exim Bank's 1.6% interest rate. It will instead be financed at a 2.4% interest rate[262] after China agreed to reduce interest rates from an originally planned rate of 3.4%.[263]

The $44 million Pakistan-China Fiber Optic Project, an 820 km long fiber optic wire connecting Pakistan and China, will be constructed using concessionary loans at an interest rate of 2%, rather than the 1.6% rate applied to other projects.[264]

Interest-free loans

[edit]In August 2015, the government of China announced that concessionary loans for several projects in Gwadar totaling $757 million would be converted to 0% interest loans.[84] The projects now financed by these 0% interest loans include: the $140 million East Bay Expressway project, the installation of breakwaters in Gwadar costing $130 million, a $360 million coal power plant in Gwadar, a $27 million project to dredge berths in Gwadar harbor, and a $100 million 300-bed hospital in Gwadar.[84] As a result, Pakistan only has to repay the principal on these loans.

In September 2015, the government of China also announced that the $230 million Gwadar International Airport project would no longer be financed by loans, but would instead be constructed with grants, which the government of Pakistan will not be required to repay.[252]

Private consortia

[edit]Energy projects worth $15.5 billion are to be constructed by joint Chinese-Pakistani firms rather than by the governments of China or Pakistan. The Exim Bank of China will finance these investments at 5–6% interest rates, while the government of Pakistan will be contractually obliged to purchase electricity from these firms at pre-negotiated rates.[179]

For example, the 1,223 MW Balloki Power Plant does not benefit from the concessionary loan rate of 1.6% because it is not being developed by the Pakistani government. Instead, it is considered a private sector investment, with its construction undertaken by a consortium of Harbin Electric and Habib Rafiq Limited, which won the bid against international competitors.[265] Chinese state-owned banks will provide loans to the consortium at an interest rate of 5%,[266] while the Pakistani government will purchase electricity at the lowest bid rate of 7.973 cents per unit.[265]

ADB assistance

[edit]The Hazara Motorway is considered a crucial part of the route between Gwadar and China. However, M-15 will not be financed by CPEC funds. Instead, it will be funded by the Asian Development Bank.[156]

The N70 project, while not officially part of CPEC, will connect CPEC's Western Alignment to the Karachi-Lahore Motorway at Multan. It will be financed as part of a $195 million package by the Asian Development Bank, announced in May 2015, which aims to upgrade the N70 National Highway and N50 National Highway.[147] In January 2016, the United Kingdom's Department for International Development announced a $72.4 million grant for roadway improvements in Balochistan, reducing the total Asian Development Bank loan from $195 million to $122.6 million.[148]

The M-4 Motorway between Faisalabad and Multan is not financed by the Chinese government as part of CPEC. Instead, it will be the first infrastructure project partially financed by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, with co-financing from the Asian Development Bank for a total of approximately $275 million.[132] Portions of the project will also be funded by a $90.7 million grant announced in October 2015 by the government of the United Kingdom for the construction of the Gojra-Shorkot section of the M4 Motorway project.[155]

Impact

[edit]As of early 2024, CPEC is the most developed land corridor of the BRI.[267]: 42 CPEC runs through twelve cities with over one million inhabitants and eighteen cities with populations over 100,000.[267]: 42

On 8 January 2017, Forbes claimed that CPEC is part of China's vision to shape the rules of the next era of globalization and keep its export and investment engines running for years to come.[268]

According to China's prime minister, Li Keqiang, Pakistan's development through the project might "wean the populace from fundamentalism".[11]

In part because of the impact of CPEC, former EU diplomat Bruno Maçães describes the BRI as the world's first transnational industrial policy, as it extends beyond national policy to influence the industrial policy of other states.[267]: 165

Pakistani economy

[edit]The CPEC is considered a landmark project in the history of Pakistan, representing the largest investment the country has attracted since its independence and the largest by China in any foreign country.[269][270] CPEC is considered economically vital to Pakistan, helping to drive its economic growth.[271] The Pakistani media and government have called CPEC investments a "game and fate changer" for the region,[272][273] with both China and Pakistan aiming for the massive investment plan to transform Pakistan into a regional economic hub and further deepen the ties between the two countries.[274] Approximately one year after the announcement of CPEC, Zhang Baozhong, chairman of China Overseas Port Holding Company, told The Washington Post that his company planned to spend an additional $4.5 billion on roads, power, hotels, and other infrastructure for Gwadar's industrial zone,[15] representing one of the largest sums of foreign direct investment into Pakistan.

As of early 2017, Pakistan faced regular energy shortfalls of over 4,500 MW,[56] resulting in routine power cuts of up to 12 hours per day,[57] which were estimated to reduce its annual GDP by 2–2.5%.[57] The Financial Times noted that these electricity shortages are a significant hindrance to foreign investment, and that Chinese investments in Pakistani infrastructure and power projects are expected to create a "virtuous cycle," making the country more attractive for foreign investment across various sectors.[275] The World Bank considers the poor availability of electricity to be a major constraint to both economic growth and investment in Pakistan.

The impact of Chinese investments in the energy sector became evident by December 2017, when Pakistan achieved a surplus in electricity production. The Pakistani Federal Minister for Power Division, Awais Leghari, announced the complete end of power cuts in 5,297 out of a total of 8,600 feeders. He also claimed that the country's electricity production had increased to 16,477 megawatts, which was 2,700 megawatts more than the demand.[276]

Pakistan's large textile industry has been severely impacted by prolonged power cuts, leading to the shutdown of nearly 20% of textile factories in Faisalabad due to power shortages.[277] The CPEC's "Early Harvest" projects are expected to address these power shortages by 2018, increasing Pakistan's power generation capacity by over 10,000 megawatts.[58] With improved infrastructure and energy supplies, the Pakistani government anticipates that economic growth rates will reach 7% by 2018.[278]

Former Pakistan Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz stated in May 2016 that the predicted economic growth from CPEC projects would help stabilize Pakistan's security situation.[279] The World Bank has also identified security concerns as a hindrance to sustained economic growth in Pakistan.[280]

According to Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying, the corridor will "serve as a driver for connectivity between South Asia and East Asia." Mushahid Hussain, chairman of the Pakistan-China Institute, told China Daily that the economic corridor "will play a crucial role in the regional integration of 'Greater South Asia', which includes China, Iran, Afghanistan, and stretches all the way to Myanmar."[39] When fully built, the corridor is expected to generate significant revenue from transit fees levied on Chinese goods, amounting to several billion dollars per annum.[281] The Guardian noted that "The Chinese are not just offering to build much-needed infrastructure but also to make Pakistan a key partner in its grand economic and strategic ambitions."[282]

Moody's Investors Service has described the project as "credit positive" for Pakistan. In 2015, the agency acknowledged that while much of the project's key benefits would not materialize until 2017, it believed that some of the economic corridor's benefits would likely begin accruing even before then.[283] The Asian Development Bank stated, "CPEC will connect economic agents along a defined geography. It will provide a connection between economic nodes or hubs, centered on urban landscapes, where large amounts of economic resources and actors are concentrated. They link the supply and demand sides of markets."[284] On 14 November 2016, Hyatt Hotels Corporation announced plans to open four properties in Pakistan, in partnership with the Bahria Town Group, citing CPEC investment as the reason behind the $600 million investment.[285]

On 12 March 2017, a consortium of Pakistani broker houses reported that Pakistan would end up paying $90 billion to China over a span of 30 years, with annual average repayments of $3–4 billion per year after fiscal year 2020. The report further stated that CPEC-related transportation would earn Pakistan $400–500 million per annum and could increase Pakistani exports by 4.5% annually until fiscal year 2025.[286]

Chinese economy

[edit]CPEC has been a significant factor in helping China improve its position in global value chains.[267]: 42

The importance of CPEC to China is reflected in its inclusion in China's 13th five-year development plan.[287][288] CPEC projects will provide China with an alternative route for energy supplies and a new trade route for Western China. Pakistan stands to gain from infrastructure upgrades and a more reliable energy supply.[289][290]

CPEC and the "Malacca Dilemma"

[edit]

The Straits of Malacca provide China with its shortest maritime route to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.[291] Approximately 80% of its Middle Eastern energy imports also pass through the Straits of Malacca.[292] As the world's largest oil importer,[45] energy security is a major concern for China, especially since current sea routes used for importing Middle Eastern oil are frequently patrolled by the United States Navy.[citation needed]

If China were to face hostile actions from the United States[who?], energy imports through the Straits of Malacca could be disrupted, potentially threatening the Chinese economy—a scenario often referred to as the "Malacca Dilemma".[292] Besides the vulnerabilities in the Straits of Malacca, China is also reliant on sea routes that pass through the South China Sea, near the disputed Spratly and Paracel Islands, which are sources of tension among China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and the United States.[293] The CPEC project aims to allow Chinese energy imports to bypass these contentious areas, offering an alternative route through the west and potentially reducing the likelihood of confrontation between the United States and China.[294] However, there is evidence suggesting that pipelines from Gwadar to China would be very costly, face significant logistical challenges, including difficult terrain and potential terrorism, and would have minimal impact on China's overall energy security.[295]

China's stake in Gwadar will also allow it to expand its influence in the Indian Ocean, a vital route for oil transportation between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Another advantage to China is that it will be able to bypass the Strait of Malacca. As of now, 60 percent of China's imported oil comes from the Middle East, and 80 percent of that is transported to China through this strait, the dangerous, piracy-rife maritime route through the South China, East China, and Yellow Seas.

Access to western China

[edit]The CPEC Alignments will enhance connectivity to the restive Xinjiang region, boosting its potential to attract both public and private investment.[291] The project is central to China–Pakistan relations, as evidenced by its inclusion in China's 13th five-year development plan.[287][288] Additionally, CPEC will support China's Western Development plan, which targets Xinjiang as well as the neighboring regions of Tibet and Qinghai.[297]

Beyond reducing China's reliance on the Sea of Malacca and South China Sea routes, CPEC will offer a shorter and more cost-effective route for energy imports from the Middle East. Currently, the sea route to China is approximately 12,000 kilometers long, while the distance from Gwadar Port to Xinjiang is about 3,000 kilometers, with an additional 3,500 kilometers from Xinjiang to China's eastern coast.[292] Consequently, CPEC is expected to significantly shorten shipping times and distances for Chinese imports and exports to the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

Route to circumvent Afghanistan

[edit]Negotiations to establish an alternate route to the Central Asian republics via China began before the announcement of CPEC. The Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement of 2010 granted Pakistan access to Central Asia through Afghanistan; however, the agreement has not been fully implemented. The Quadrilateral Agreement on Traffic in Transit (QATT), first proposed in 1995 and signed in 2004 by China, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, aimed to facilitate transit trade among these countries, excluding Afghanistan.[298] Despite the signing of the QATT, its full potential was never realized, primarily due to inadequate infrastructure links between the four countries before the announcement of CPEC.

During Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's visit to India in April 2015, he stated, "We will not provide equal transit access to Central Asia for Pakistani trucks," unless the Pakistani government included India in the 2010 Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement.[299] The current Transit Trade Agreement allows Afghanistan to access the Port of Karachi for export trade with India and permits Afghan goods to be transited to any border of Pakistan. However, it does not grant Afghan trucks the right to cross the Wagah Border or allow Indian goods to be exported to Afghanistan through Pakistan.[300] Due to ongoing tensions between India and Pakistan, the Pakistani government was hesitant to include India in trade negotiations with Afghanistan, resulting in limited progress between the Afghan and Pakistani sides.

In February 2016, the Pakistani government announced its intention to bypass Afghanistan entirely in its efforts to access Central Asia. The plan involved reviving the QATT to allow Central Asian states to reach Pakistani ports via Kashgar, rather than through Afghanistan,[301] thus avoiding the need to rely on a politically unstable Afghanistan as a transit corridor. In early March 2016, the Afghan government reportedly agreed to allow Pakistan to use Afghanistan as a corridor to Tajikistan, having dropped its previous demands for reciprocal access to India via Pakistan.[302]

Alternate route to Central Asia

[edit]Leaders of various Central Asian republics have expressed interest in linking their infrastructure networks to the CPEC project through China. During Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's visit to Kazakhstan in August 2015, Kazakh Prime Minister Karim Massimov conveyed Kazakhstan's desire to connect its road network to CPEC.[303] In November 2015, during Tajikistan President Emomali Rahmon's visit to Pakistan, he expressed his government's interest in joining the Quadrilateral Agreement on Traffic in Transit to use CPEC as a route for imports and exports to Tajikistan, bypassing Afghanistan.[304] This request received political support from the Pakistani Prime Minister.[304]

The Chinese government has already upgraded the road linking Kashgar to Osh in Kyrgyzstan via the Kyrgyz town of Erkeshtam. Additionally, a railway between Urumqi, China, and Almaty, Kazakhstan, has been completed as part of China's One Belt One Road initiative.[305] Numerous land crossings already exist between Kazakhstan and China. The Chinese government has also announced plans to lay railway tracks from Tashkent, Uzbekistan, towards Kyrgyzstan, with onward connections to China and Pakistan.[306] Furthermore, the Pamir Highway provides Tajikistan access to Kashgar via the Kulma Pass. These connections complement the CPEC project by offering Central Asian states access to Pakistan's deepwater ports, effectively bypassing Afghanistan, which has been plagued by civil war and political instability since the late 1970s.

Comparison to Chabahar Port

[edit]In May 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani signed a series of twelve agreements in Tehran. India agreed to refurbish one of Chabahar's ten existing berths and reconstruct another at the Port of Chabahar.[307] This upgrade aims to facilitate the export of Indian goods to Iran, with potential onward connections to Afghanistan and Central Asia.[308] As of February 2017, the project has been delayed, with both Iran and India blaming each other for the hold-ups.[309]

A segment of the Indian media referred to it as "a counter to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor,"[310] although the total financial value of the projects has been noted to be significantly lower than that of CPEC.[311]

As part of the twelve memorandums of understanding signed by the Indian and Iranian delegations, according to the text released by India's Ministry of External Affairs, India will extend a $150 million line of credit through the Exim Bank of India.[312] Additionally, India Ports Global signed a contract with Iran's Aria Banader to develop berths at the port,[313] at a cost of $85 million[314] over a period of 18 months.[315]

Under the agreement, India Ports Global will refurbish a 640-meter-long container handling facility and reconstruct a 600-meter-long berth at the port.[307] Additionally, India agreed to extend a $400 million line of credit for the import of steel to construct a rail link between Chabahar and Zahedan.[316] Moreover, India's IRCON and Iran's Construction, Development of Transport and Infrastructure Company Archived 20 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine signed a memorandum of understanding regarding the construction and financing of the Chabahar to Zahedan rail line, with a total cost estimated at $1.6 billion.[317]

India's Highways and Shipping Minister, Nitin Gadkari, suggested that the free trade zone in Chabahar has the potential to attract investments of over $15 billion in the future.[318] However, he emphasized that such investments are dependent on Iran offering India natural gas at a rate of $1.50 per million British Thermal Units—a price significantly lower than the $2.95 per million British Thermal Units currently offered by Iran.[319] The two countries also signed a memorandum of understanding to explore the possibility of establishing an aluminum smelter at a cost of $2 billion,[citation needed] as well as a urea processing facility in Chabahar,[320] though these investments are also contingent upon Iran providing low-cost natural gas for their operation.[321]

India, Iran, and Afghanistan also signed an agreement aimed at simplifying transit procedures between the three countries.[314] Although there is a desire to bypass Pakistan to strengthen economic ties between Iran and India, Indian goods bound for Iran do not currently require transit through Pakistan. These goods can be exported via Bandar Abbas, where India maintains a diplomatic mission.[322] Bandar Abbas is also considered a crucial node on the North–South Transport Corridor, which has been supported by India and Russia since 2002.[323][324] Additionally, Indian goods can be imported and transported across Iran via Bandar-e Emam Khomeyni, near the Iraqi border.

Under the Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement, Afghan goods can be transported through Pakistan for export to India; however, Indian goods cannot be exported to Afghanistan via Pakistan.[325] Once Chabahar is fully operational, Indian exporters will potentially be able to export goods to Afghanistan, a country with an annual gross domestic product of approximately $60.6 billion.[326]

Following the agreement's signing, Iran's ambassador to Pakistan, Mehdi Honerdoost, mentioned that the deal was "not finished" and that Iran would be open to including both Pakistan and China in the project.[327] He clarified that Chabahar Port was not intended to compete with Pakistan's Gwadar Port,[328] and noted that both Pakistan and China were invited to participate in the project before India, but according to Pakistani media, neither country expressed interest in joining.[329][330]

However, the Iranian ambassador eventually clarified that Iran does not view Chabahar as a project capable of rivaling CPEC, stating, "Iran is eager to join CPEC with its full capabilities, possibilities, and abilities."[331]

In July 2020, Pakistani media outlet The News International reported that the Iranian government had removed India from a long-stalled rail project, opting instead to sign a comprehensive deal with China.[332] This report was later refuted by the Iranian government, which clarified that India’s investments were never connected to the railway project in the first place.[333][334]

Environment

[edit]Pakistan is already facing significant challenges from climate change and global warming, with about 5,000 of its glaciers melting at an alarming rate. The country is also experiencing extreme weather patterns and seasonal shifts in recent years.[335] The coal-based power plants under the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) are not aligned with Pakistan's green policy. It is estimated that by 2030, carbon dioxide emissions from CPEC projects will total 371 metric tonnes, with 56% of these emissions coming from the energy sector. CPEC also anticipates a daily commute of 7,000 trucks, potentially emitting 36.5 million tons of CO2.[336]

Since 2021, under growing pressure due to being the world's largest polluter, China has shifted its focus from coal-based energy investments in Pakistan to renewable energy. This shift aims to promote a more "green" image of CPEC.[337]

Security Issues

[edit]The Pakistan Army has assumed responsibility for the security of CPEC employees and investors, strengthening the relationship between China and Pakistan. However, the areas through which the corridor passes are plagued by conflict, with Chinese workers frequently targeted in regions where Islamic jihadists and Baloch separatist forces are active. The Pakistani Taliban has also threatened to attack China's Belt and Road route unless a "tax" is paid.[338]

Security forces