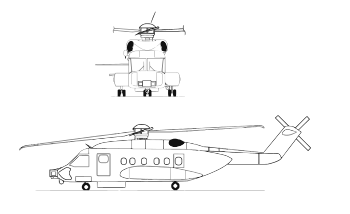

Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclone

| CH-148 Cyclone | |

|---|---|

A CH-148 in 2020 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Maritime helicopter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| Status | In service[1] |

| Primary user | Royal Canadian Air Force |

| Number built | 26 as of Dec. 2022[2] |

| History | |

| Introduction date | July 2018[1] |

| First flight | 15 November 2008 |

| Developed from | Sikorsky S-92 |

The Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclone is a twin-engine, multi-role shipborne helicopter developed by the Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation for the Canadian Armed Forces.[3][4] A military variant of the Sikorsky S-92, the CH-148 is designed for shipboard operations and replaced the CH-124 Sea King, which was in Canadian Armed Forces operation from 1963 to 2018.

The Cyclone entered operational service with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in 2018 and now conducts anti-submarine warfare (ASW), surveillance, and search and rescue missions from Royal Canadian Navy frigates. The helicopter also performs utility and transport roles in support of national and international security efforts.[5] In 2004, Canada awarded Sikorsky Aircraft a contract for 28 CH-148s with deliveries originally planned to start in 2009. Deliveries were repeatedly delayed due to development issues and difficulty fulfilling contract requirements; the first deliveries, involving six initial helicopters (designated as Block 1), occurred during June 2015. Three years later, the Cyclone Block 2 achieved initial operating capability (IOC). The fleet was briefly grounded in early 2020 following a crash that was attributed to poor documentation and software flaws.

Development

[edit]Origins

[edit]Canada began to seek a replacement for the Sea King maritime helicopter in 1986 when it issued a solicitation for the New Shipborne Aircraft (NSA) Project. A variant of the AgustaWestland EH101 was selected and a contract was signed by the nation's governing party at the time, the Progressive Conservatives. After a change of government to the Liberal party, the EH-101 contract was cancelled. The cancellation resulted in a lengthy delay to procure a replacement aircraft. The project took on increased importance in the early 2000s and another procurement competition was initiated.[6]

On 23 November 2004, Canada's Department of National Defence announced the award of a CA$1.8 billion contract to Sikorsky to produce 28 helicopters, with deliveries scheduled to start in January 2009.[7] In addition, Sikorsky's subcontractors, General Dynamics Canada and L-3 MAS are responsible for in-service maintenance and the Maritime Helicopter Training Centre including two Operational Mission Simulators. Other elements of in-service support include the Integrated Vehicle Health Monitoring System, spares and software support.[8]

The first flight of the first production CH-148, serial number 801 (FAA registration N4901C), took place in Florida on 15 November 2008.[9][10]

Delays and upgrades

[edit]In May 2010, Sikorsky announced an engine upgrade for the CH-148 Cyclone by the end of 2012. General Electric was developing a new engine version based on the CT7-8A1. The CT7-8A1 makes the CH-148 Cyclone heavier and less efficient than expected. General Electric developed the CT7-8A7 to be certified by June 2012 and eventually integrated into the Cyclone as soon as possible. General Electric developed the upgraded engine at its own expense. The new CT7-8A7 engine version produces 10% additional horsepower.[11] The CT7-8A7 included modifications to the fuel manifold and nozzles. Interim CH-148s were to be provided with CT7-8A1 engines.[12]

Additional complications in the program, and restrictions from US government International Traffic in Arms Regulations delayed initial aircraft deliveries until 2010.[13] Further delays resulted in expected delivery pushed to 2015.[14] In 2013 Canada rejected the delivery of "interim" helicopters offered by Sikorsky that lacked critical mission systems.[15] In September 2013, the Canadian government announced that they were reevaluating the CH-148 purchase, and would examine cancelling the contract and ordering different helicopters if that were the better option;[16] by this point, Sikorsky had accrued over $88 million in late damages since 2008.[17]

In June 2014, it was announced that the Canadian government had removed the mandatory requirement from Sikorsky to supply the CH-148 with a 30-minute run-dry main gearbox. This was a key safety feature defined as mandatory in the original RFQ and one of 7 concessions made to Sikorsky.[18] The Canadian government stated that these concessions would not affect the safety of Armed Forces personnel. However, oil loss in the main gearbox followed by several other factors caused the 2009 crash of a S-92, a civil version of the helicopter, off the coast of Newfoundland.[19][20] Sikorsky added an oil cooler bypass switch and stated a similar accident is extremely unlikely.[21] The effectiveness of the bypass switch has been questioned as it assumes that the leak will happen within the oil cooler assembly, and that the bypass can be activated in time to maintain enough oil. In the case of the S-92 crash, a titanium stud sheared causing catastrophic oil loss through the oil filter assembly.[22]

Design

[edit]

The CH-148 has a metal and composite airframe. The four-bladed articulated composite main rotor blade is wider and has a larger diameter than the S-70 Blackhawk. The tapered blade tip sweeps back and angles downward to reduce noise and increase lift. Tethered hover flight has recorded 138 kN (31,000 lbf) of lift generated, both in and out of ground effect. Unlike the Sea King, but in common with almost all current production naval helicopters, the Cyclone is not amphibious and cannot float on water.

A number of safety features such as flaw tolerance, bird strike capability and engine burst containment have been incorporated into the design. An active vibration system ensures comfortable flight and acoustic levels are well below certification requirements. The Cyclone will feature a modified main gearbox, which has been redesigned since a March 2009 accident.[23]

The CH-148 is equipped with devices to search and locate submarines during ASW, and is equipped with countermeasures to protect itself against missile strikes. The Integrated Mission System is being developed by General Dynamics Canada,[24] as is the Sonobuoy Acoustic Processing System.[25] The radar is a Telephonics APS-143B,[26] the EO System a Flir Systems SAFIRE III,[27] the sonar an L-3 HELRAS,[28] and the ESM, a Lockheed Martin AN/ALQ-210.[29] CMC Electronics provides the flight management system, named CMA-2082MH Aircraft Management System.[30]

Operational history

[edit]The Canadian Forces were to take delivery of CH-148s beginning in November 2008. In April 2009 the Government of Canada waived late fees and allowed Sikorsky two additional years to deliver compliant Cyclones. In February 2010, the first CH-148 arrived at CFB Halifax. Shearwater Heliport is the headquarters of 12 Wing, which were operating the CH-124 Sea King. Due to delays and export restrictions, the first 19 of the 28 CH-148 Cyclones were to be delivered in an interim standard which does not meet the original contract requirements. This allows operational testing and training to begin before the end of the year.[31][32]

In March 2010, the first CH-148 was embarked on HMCS Montréal for an intensive open seas trials including landing and takeoff.[33][34] In June 2010, Sikorsky announced the Canadian Forces would receive six interim CH-148 Cyclones in November 2010.[35] In July 2010, Sikorsky reached an agreement on delay payments and deliveries; deliveries of the remaining CH-148s with full capabilities were to begin in June 2012.[36] All interim-standard helicopters were to be retrofitted by December 2013.[37]

On 22 February 2011, the Office of the Prime Minister of Canada announced the proposed arrival of nine Cyclones on Canada's west coast in the spring of 2014.[38] By March 2011 the six interim CH-148s had not been delivered. On 3 March 2011, the federal government announced that it would impose a fine of up to CA$8 million on Sikorsky for failure to meet contractual obligations.[39] In January 2012 it was reported Sikorsky would deliver five training CH-148s in 2012, including one "fully mission capable" CH-148 by June 2012, or face a further possible $80 million in contract penalties.[40] On 10 July 2012 in reference to Sikorsky missing another delivery deadline, Defence Minister Peter MacKay called the Cyclone purchase "the worst procurement in the history of Canada".[41]

In December 2012, Louis Chenevert, chairman of Sikorsky's parent corporation United Technologies Corporation, stated that the five CH-148s scheduled for delivery in 2012 would instead be delivered in 2013, along with three additional helicopters. The remaining deliveries are to follow.[42][43] In October 2013, the project appeared to be on the verge of cancellation with the Canadian government ordering a possible change to the maritime helicopter requirements.[44]

In June 2015, it was reported that Sikorsky was ready to begin deliveries of the first interim Cyclones to the Royal Canadian Air Force.[45] Six helicopters were delivered on 19 June 2015,[46] and two "Block 1.1" Cyclones were delivered in November–December 2015. These eight helicopters will allow for RCAF training on the Cyclone until the fully operational Block 2 Cyclones start to arrive in 2018.[47] A ninth CH-148 was delivered in August 2016.[48] The eleventh helicopter was delivered in March 2017 as deliveries of the weapons system continue.[49] In June 2018, the Cyclone was declared to have reached its "initial operating capability".[50]

In July 2018, the RCAF announced that the Cyclone was assigned to a Canadian deployment as part of Operation Reassurance, with one helicopter leaving Canada on board HMCS Ville de Québec.[1]

In December 2021, the RCAF found cracks on the tails of 19 of the 23 CH-148s which had been delivered, leaving only 2 CH-148s without defects (the other 2 were already in long-term maintenance and had not been inspected), compromising Operation Lentus.[51] The RCAF claimed that the issue had been addressed by the end of 2021, and CH-148 detachments continued to be deployed frequently on operations around the world throughout 2022. By December 2022, 26 out of 28 helicopters had been delivered, with most in Block 2 configuration.[52]

Operators

[edit]- Royal Canadian Air Force – 26 helicopters delivered as of December 2022,[53] out of 28 total ordered. One helicopter was lost at sea in 2020.[54][50]

- 406 Maritime Operational Training Squadron - since summer 2016

- 423 Maritime Helicopter Squadron - since January 2018

- 443 Maritime Helicopter Squadron - since August 2018

Accidents

[edit]- On 29 April 2020, an RCAF CH-148 from 423 Maritime Helicopter Squadron, attached to HMCS Fredericton and based at the Shearwater Heliport crashed in the Ionian Sea during a NATO Mediterranean exercise, killing all six crew members aboard.[55][56] As a result, all Cyclones in service were placed on an "operational pause"[57] until it was lifted on 16 June 2020.[58] An investigation attributed the accident to the electronic control system and fly-by-wire control law known as "Command Model Attitude Bias Phenomenon". This resulted in the CH-148 responding insufficiently to pilot inputs when the flight director was engaged. The investigation concluded that manufacturer-supplied materials contained "misleading or confusing" information, incomplete sections on automation and lacked manoeuvre descriptions. The recommended fix was to modify software governing the electronic flight control laws and enhance flight mode annunciation and awareness to the crew.[59]

Specifications

[edit]

Data from Canadian Forces MHP page & RCAF CH-148 profile.[60][61][62]

General characteristics

- Crew: 4 (2 pilots; 1 tactical coordinator, ACSO; 1 sensor operator, AES OP)

- Capacity: 6 in mission configuration, up to 22 in utility configuration.

- Length: 56 ft 2 in (17.12 m) .

- Folded Length: 14.78 m (48.5 ft)

- Width: 17 ft 3 in (5.26 m) fuselage

- Height: 15 ft 5 in (4.70 m) S-92

- Empty weight: 15,600 lb (7,076 kg) S-92

- Max takeoff weight: 29,300 lb (13,290 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric CT7-8A7 turboshaft engines, 3,000 shp (2,200 kW) each

- Main rotor diameter: 58 ft 1 in (17.70 m)

- Main rotor area: 2,650 sq ft (246 m2) S-92

- Blade section: - root: Sikorsky SC2110; tip: Sikorsky SSC-A09 - S-92[63]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 165 kn (190 mph, 306 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 137 kn (158 mph, 254 km/h)

- Service ceiling: 15,000 ft (4,600 m)

Armament

- 2 × MK-46 torpedoes on BRU-14 mounted in folding weapons pylons

- Door-arm mounted general-purpose machine gun

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- AgustaWestland AW101/AgustaWestland CH-149 Cormorant

- Eurocopter AS532 SC Cougar

- Kamov Ka-27

- NHIndustries NH90

- Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King/Sikorsky CH-124 Sea King

Related lists

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Pugliese, David (11 July 2018). "RCAF's Cyclone helicopter to go on first international deployment next week". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ "The RCAF's Rotary Fleet". Canadian Defence Review Vol. 28 Issue 6, p. 78, Dec. 2022.

- ^ "Government of Canada proceeds with CH-148 Cyclone Procurement". Canadian American Strategic Review. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Background – CF Maritime Helicopter – Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclone". Canadian American Strategic Review. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

Finally, in late 2003 there was a call for tenders. A winner was announced in July of 2004. The new Maritime Heli-copter would be Sikorsky's H-92 Superhawk which will be the CH-148 Cyclone in CF service.

- ^ "CH-148 Cyclone". Department of National Defence. Canada's Air Force. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Pigott, Peter (2012). "Playing the Waiting Game". Helicopters magazine. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Background Information CH-148 Cyclone Helicopter". Department of National Defence. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Orr, John (Summer 2008). "Making Waves" (PDF). Canadian Naval Review. Vol. 4, no. 2. pp. 31–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig (18 November 2008). "First flight for Canada's Cyclone maritime helicopter". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Osborne, Tony. "Sikorsky flies first CH-148 Cyclone". Rotorhub.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009 – via shephard.co.uk.

- ^ "De nouvelles configurations des moteurs pour les hélicoptères maritimes canadiens". TV5 (in French). 21 May 2010. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ Tutton, Michael (21 May 2010). "Another engine change for Navy choppers". MSN News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Security Restrictions May Hamper Canadian Purchases". Aviation Today. 27 March 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015.

- ^ Byers, Michael; Webb, Stewart (23 July 2013). "Replace the Sea Kings. Now". National Post. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.

- ^ Pugliese, David (20 July 2013). "Canada Refuses To Accept Sikorsky Helos". Defense News. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013.

- ^ Brewster, Murray (5 September 2013). "Military team sent to evaluate helicopters 'other' than troubled Cyclones". CTV News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.

- ^ Chase, Steve (5 September 2013). "Helicopter purchase's fate in doubt as Ottawa examines other models". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013.

- ^ Cudmore, James (23 June 2014). "Sea King replacements: $7.6B Cyclone maritime helicopters lack key safety requirement". CBC News.

- ^ "TSB Accident Investigation Report A09A0016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ Daly, Paul (9 February 2011). "Inquiry finds 16 separate problems in 2009 Nfld. helicopter crash". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Assessment of the Responses to Aviation Safety Recommendation A11-01". Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ Cheney, Peter (23 November 2009). "Chopper in fatal crash failed safety test". The Globe and Mail. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016.

- ^ Warwick, Graham. "Canada Wants Tougher Helicopter Gearbox Rules"[permanent dead link]. Aviation Week, 14 February 2011.

- ^ General Dynamics Canada – CH148 Cyclone – Maritime Helicopter Project – Overview Archived 2 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, gdcanada.com

- ^ General Dynamics Canada – Sonobuoy Acoustic Processing Systems – Overview Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, gdcanada.com

- ^ Telephonics: Corporate Info Archived 27 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, telephonics.com

- ^ FLIR – News Release Archived 25 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, corporate-ir.net

- ^ HELRAS DS-100 – Helicopter Long-Range Active Sonar Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. L-3mps.com

- ^ Lockheed Martin Awarded $59.4 Million to Provide Electronic Support Measure Systems to Canadian Forces Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Lockheed Martin.

- ^ CMC Electronics Awarded Contract by Sikorsky Aircraft to Supply Next-Generation Aircraft Management System for Canadian H-92 Maritime Helicopter Project Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. esterline.com

- ^ "Sikorsky's Cyclone Touches Down in Canada". Aviation Week. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Photos of the Cyclone Helicopter at Shearwater: More Tests Expected Next Month". Defence Watch. 12 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ "Cyclone testing comes to Halifax". The Chronicle Herald. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Sikorsky's CH-148 Cyclone naval helicopter prototype arrives in Canada for trials". Defense Industry Daily. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Six choppers to be delivered to navy by summer 2012". CTV News. The Canadian Press. 8 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (28 July 2010). "Sikorsky accepts concessions to Canada after new CH-148 delays". Flight International. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010.

- ^ Maritime Helicopter Project (MHP) Schedule[permanent dead link] Materiel Group, Department of National Defence, 16 February 2011.

- ^ "New helicopter facility at Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt" (Press release). Prime Minister of Canada. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011.

- ^ Leblan, Daniel (3 March 2011). "Ottawa Seeks Cash for Copter Delays". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Only five 'training' choppers expected this year". The Chronicle Herald. 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Mackay blames grits for worst procurement in history in chopper deal". The Chronicle Herald. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Pugliese, David (18 December 2012). "Delivery of Sea King replacement helicopters delayed once again". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012.

- ^ Pugliese, David (19 December 2012). "Sea King replacement delayed". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013 – via canada.com.

- ^ Cudmore, James (15 October 2013). "Sea King replacements could be smaller, cheaper helicopters". CBC News. Toronto. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013.

- ^ Pugliese, David (18 June 2015). "Cyclone helicopter is finally ready for the RCAF….sort of". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "CH-148 Cyclone maritime helicopter delivery announced". CBC News. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Rempel, Roy (April 2016). "NSPS and the Coming Defence Review". Canadian Defence Review. 22 (2): 97–101.

- ^ Drew, James (11 August 2016). "Canada Begins Withdrawing CH-124s As 9th CH-148 Arrives". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016.

- ^ "Maritime Helicopter Project". Defence Canada. 9 March 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ a b "CH-148 Cyclone procurement project". Government of Canada. 16 July 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ MacDonald, Michael (5 December 2021). "Military repairing cracks in the tails of 19 CH-148 Cyclone maritime helicopters". CTV News. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "The RCAF's Rotary Fleet". Canadian Defence Review Vol. 28 Issue 6, p. 78, Dec. 2022

- ^ "The RCAF's Rotary Fleet". Canadian Defence Review Vol. 28 Issue 6, p. 78, Dec. 2022

- ^ "Decades-long mission to replace Sea Kings hits another snag". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Ahronheim, Anna (30 April 2020). "Canadian military helicopter crashes during NATO exercise". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Military says remains of all 6 who died in Cyclone helicopter crash now identified". CBC News. The Canadian Press. 20 June 2020. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "Search concludes for crashed chopper and lost Canadian service members". CBC News. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Operational pause of CH-148 Cyclone fleet lifted" (Press release). Government of Canada. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "CH148822 Cyclone - Epilogue". Royal Canadian Air Force. 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "The Maritime Helicopter Project – PMO MHP". Canadian Forces. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "Sikorsky CH148 Cyclone Helicopter". www.lockheedmartin.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "CH-148 Cyclone". Royal Canadian Air Force. 10 April 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.