Floyd Bennett Field

Floyd Bennett Field Historic District | |

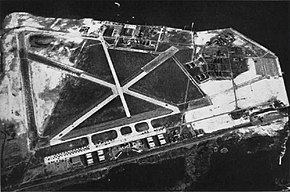

Floyd Bennett Field in 2006 | |

| |

| Location | Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn, New York |

|---|---|

| Built | 1928–1930 |

| Architect | Department of Docks |

| Architectural style | |

| NRHP reference No. | 80000363[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 11, 1980 |

Floyd Bennett Field is an airfield in the Marine Park neighborhood of southeast Brooklyn in New York City, along the shore of Jamaica Bay. The airport originally hosted commercial and general aviation traffic before being used as a naval air station. Floyd Bennett Field is currently part of the Gateway National Recreation Area's Jamaica Bay Unit, and is managed by the National Park Service (NPS). While no longer used as an operational commercial, military, or general aviation airfield, a section is still used as a helicopter base by the New York City Police Department (NYPD), and one runway is reserved for hobbyists flying radio-controlled aircraft.

Floyd Bennett Field was created by connecting Barren Island and several smaller islands to the rest of Brooklyn by filling the channels between them with sand pumped from the bottom of Jamaica Bay. The airport was named after Floyd Bennett, a noted aviator who piloted the first plane to fly over the North Pole and had visualized an airport at Barren Island before dying in 1928; construction on Floyd Bennett Field started the same year.[2] The airport was dedicated on June 26, 1930,[3] and officially opened to commercial flights on May 23, 1931.[4] Despite the exceptional quality of its facilities, Floyd Bennett Field never received much commercial traffic, and it was used instead for general aviation. During the interwar period, dozens of aviation records were set by aviators flying to or from Floyd Bennett Field.[5]

Starting in the 1930s, the United States Coast Guard and United States Navy occupied part of the airport. With the outbreak of World War II, Floyd Bennett Field became part of Naval Air Station New York on June 2, 1941,[6][7] and Floyd Bennett Field was a hub for naval activities during World War II. After the war, the airfield remained a naval air station operated as a Naval Air Reserve installation. In 1970, the Navy stopped using NAS New York / Floyd Bennett Field,[8] though a non-flying Naval Reserve Center remained until 1983. The Coast Guard continued to maintain Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn for helicopter operations that remained through 1998 when it, too, was decommissioned. Following the Navy's departure, several plans for the use of Floyd Bennett Field were proposed, although use as a civilian airport for fixed-wing operations was considered untenable due to the proximity to and extensive commercial air traffic associated with, John F. Kennedy International Airport. In 1972, it was ultimately decided to integrate the airport into the Gateway National Recreation Area. Floyd Bennett Field reopened as a park in 1974.[9]

Many of the earliest surviving original structures are included in a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places, being among the largest collections and best representatives of commercial aviation architecture from the period, and due to the significant contributions to general aviation and military aviation made there during the Interwar period.[1] Floyd Bennett Field also contains facilities such as a natural area, a campground, and grasslands.[10]

History

[edit]

Planning

[edit]Need for an airport

[edit]Floyd Bennett Field was New York City's first municipal airport, built largely in response to the growth of commercial aviation after World War I.[11][12] During the 1920s, air travel in Europe was more popular than in the United States because, although Europe had a surplus of airplanes, the United States already had a national railroad system, which reduced the need for commercial aircraft.[13][12][14] While other localities (such as Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Cleveland, Ohio) had municipal airports, New York City had a multitude of private airfields, and thus did not see the need for a municipal airport until the late 1920s.[15][12]

The New York City Board of Estimate submitted a recommendation for a New York City municipal airport in 1925, but it was denied. Two years later, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced a similar recommendation, which was largely ignored.[16] By this time, the city urgently needed an airport. This was underscored by the construction of the Newark Metropolitan Airport in 1928, as well as several transatlantic flights from the New York area that were piloted by such figures as Charles Lindbergh, Clarence D. Chamberlin, and Charles A. Levine.[17][14] Most of the nation's air traffic around this time was from airmail operations, and the United States Postal Service designated Newark Airport as the airmail terminal for the New York City area, since Newark was the region's best-equipped airport for airmail traffic.[18][14] New York City officials decided that an airport in the city itself was necessary, because placing the airmail terminal in Newark represented a missed opportunity to put New York City on the aviation map.[14]

In mid-1927, Herbert Hoover, the United States Secretary of Commerce, approved the creation of a "Fact-Finding Committee on Suitable Airport Facilities for the New York Metropolitan District".[19] The Hoover committee, composed of representatives from New York and New Jersey,[20] identified six general locations in the metropolitan area where an airport could be built.[21] The committee recommended Middle Village, in Central Queens, as the first location for an airfield. Its second choice was an existing airstrip on Barren Island in southeastern Brooklyn.[22] Another site in the eastern part of the bay, near the present-day JFK Airport, was also recommended.[23] At the time, the report listed three "Federal or State Fields", three "Commercial Fields", and seventeen "Intermediate Fields" in the New York metropolitan area.[20] Chamberlin was appointed as the city's aeronautical engineer to make the final decision on the airport's location.[14]

There was much debate over where the airport should be located. U.S. Representative and future New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia, himself a former military airman,[a] advocated for a commercial airport to be placed in Governors Island, as it was closer to Manhattan and located in the middle of New York Harbor. He left open the possibility that the outer boroughs could also build their own local airports.[25] La Guardia, along with Representative William W. Cohen, introduced a motion in the 70th United States Congress to establish the airport on Governors Island, but it was voted down.[26]

Site chosen

[edit]Chamberlin chose Barren Island as the site for the new municipal airport.[27][28][23] An isolated settlement[29] on the island had been developed in the late 19th century,[30] and at its peak, had been home to "several thousand" people.[29] A garbage incinerator and a glue factory had been located on the island.[29] By the 1920s, Barren Island's industrial presence had dwindled, and only a small percentage of residents remained on the island.[31] In 1927, a pilot named Paul Rizzo had opened the Barren Island Airport, a private airstrip, on the island.[32][33]

Chamberlin chose the Barren Island location over Middle Village for several reasons. First, city officials had already spent $100 million between 1900 and 1927 toward constructing a seaport in Jamaica Bay, having dredged land for the proposed shipping channels.[34][20] Chamberlin also favored the Barren Island location because of the lack of obstructions nearby, as well as the presence of Jamaica Bay, which would allow seaplanes to also use the airport.[18][35][20] Finally, the site was city-owned, while the land in Middle Village was not.[18][35][22] City officials believed that an airport at Barren Island would be able to spur development of Jamaica Bay, despite the abandonment of the seaport proposal.[18] However, airline companies feared that the Barren Island Airport would have low visibility during foggy days,[22] a claim Chamberlin disputed because he said there was little history of fog in the area.[35]

Construction

[edit]In February 1928, the Board of Estimate unanimously approved Chamberlin's suggestion to build the airport at Barren Island, allotting a 380 acres (150 ha) plot on Barren Island for that purpose. The project also received an appropriation of $500,000, paid for with taxes. One of the members of Hoover's Fact-Finding Committee objected because Middle Village was located at a higher elevation with less fog, while Barren Island was more frequently foggy during the spring and fall. However, Barren Island was already flat, so an airport located there would be ready for use in less time than an airport built on the hills of Middle Village.[36][18] After the plan was approved, two airmail companies announced that they would not move their operations from New Jersey to Barren Island, because the airmail facilities at Newark International Airport were closer to Manhattan than the proposed Barren Island Airport was.[37]

Designs for the proposed Barren Island Airport were being solicited in 1927, even before the city had given its approval of the Barren Island site. By January 1928, the New York City Department of Docks had composed its own team to create plans for the airport.[38] The future airport would be able to accommodate both airplanes and seaplanes. A "Jamaica Bay Channel" on the airport's east side would provide loading docks and hangars for seaplanes. The airplane hangars and an administrative building would occupy the northwest corner of the airport. Four runways would be built across the rest of the grass field.[28][37] By fall 1928, the Department of Docks had published a more detailed plan that would theoretically allow the Barren Island Airport to get an "A1A" rating, the highest rating for an airport awarded by the United States Department of Commerce. This new plan called for two perpendicular concrete runways in a "T" shape, with one being 3,110 feet (950 m) long and the other being 4,000 feet (1,200 m) long. An administration building, fourteen hangars, and other maintenance facilities would be constructed on the west side of the airport, parallel to Flatbush Avenue. The rest of the airport would be a grass field.[39]

The Department of Docks was in charge of constructing the Barren Island Airport.[40] The first contract for construction was awarded in May 1928. The $583,000 contract entailed filling in or leveling 4.45 million cubic yards (3,400,000 m3) of soil across a 350-acre (140 ha) parcel. Sand from Jamaica Bay was used to connect the islands and raise the site to 16 feet (4.9 m) above the high–tide mark. This contract was completed by May 1929. A subsequent contract for $75,000 involved filling in an extra 833,000 cubic yards (637,000 m3) of land, and was finished by the end of 1929.[41][40] In order to secure an "A1A" rating, the planners built 200-foot-wide (61 m) runways, twice the minimum runway width mandated by the Department of Commerce. These runways were designed for planes taking off.[42][43] The planners also constructed grass fields with several layers of soil, which would allow for smooth plane landings.[40][44] They conducted studies on other infrastructure, such as the power, sewage, and water systems, to determine what materials should be used to allow the airport to get an "AAA" rating, which was the same as an "A1A" rating.[43]

Barren Island Airport was renamed after the aviator Floyd Bennett in October 1928.[2][45] Floyd's wife, Cora, recalled that they had once toured Barren Island when Floyd said, "Some day, Cora, there will be an airport here."[46] Bennett and Richard E. Byrd claimed to have been the first to travel to the North Pole by airplane, having made the flight in May 1926, for which they both received the Medal of Honor. They were preparing to fly to the South Pole in 1927 when Bennett placed these plans on hold in order to rescue the crew of the Bremen.[47] Bennett died of pneumonia in April 1928, during the Bremen rescue mission, and he was subsequently buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery.[48][4] Many things were named after Bennett, including the aircraft Byrd and three others flew to the South Pole in 1929 and the Barren Island Airport.[4]

After the field was completely filled and leveled, the two concrete runways were built. The shorter runway was numbered 15–33 while the longer runway was numbered 6–24. At the time, Runway 6–24 was the longest concrete runway in the U.S.[49][50] The 8-inch-thick (20 cm) layer of reinforced concrete, gravel drainage strips, and extra 100-foot (30 m) width contributed to the airport's "AAA" rating.[50][51] The new airfield's runways, built at a time when most "airports" still had dirt runways and no night landings, made the airport among the most advanced of its day, as did its comfortable terminal facilities with numerous amenities.[2]

As work on the runways was ongoing, plans for the administration building and hangars were being revised. The number of hangars was reduced from fourteen to eight due to a lack of funds; the other six hangars were supposed to be built later, but it never happened.[52] After the plans were finalized in late 1929, construction started on the administration building and eight hangars.[43][42] Materials were shipped by boat to a temporary pier west of Flatbush Avenue.[49][53] In 1930, work started on the administration building.[52] The administration building was erected on the west side of the field, near Flatbush Avenue, and four hangars each were constructed to the north and south of the building.[14] The architect of the hangars and administration building is not documented, but Tony P. Wrenn, a preservation consultant, surmises that Edward C. Remson designed these structures.[43] In 1929, builders awarded contracts for hydraulic filling operations, a wooden perimeter fence, soil placement and seeding, and runway widening.[54] These contracts were substantially complete by 1930.[55]

Opening

[edit]The airport dedication occurred on June 26, 1930. A crowd of 25,000 attended this aerial demonstration led by Charles Lindbergh and Jimmy Doolittle. A flotilla of 600 U.S. Army Air Corps aircraft circled the field as part of the airport dedication. Admiral Byrd, Mayor Walker and his wife, and Cora Bennett were present at the event.[3] However, the airport was not finished at that time.[48] The administration building and parking areas had yet to be completed.[56][57] The costs of the proposed airport were increasing even as its completion was being delayed. A few days after the dedication, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the airport would not be complete until 1932 and would cost $4.5 million.[58]

Floyd Bennett Field was formally dedicated again on May 23, 1931, upon its official completion.[4][59] At the time, the Administration Building was almost finished, and the United States Navy was to occupy part of the airfield.[59] The dedication was attended by 25,000 people, including Chamberlain; Byrd; Captain John H. Towers, who flew the first transatlantic flight; F. Trubee Davison, the assistant United States Secretary of the Army for Aviation; and Colonel Charles Lindbergh, who flew the first solo transatlantic flight.[4] Many of the attendees were also there to view the largest aircraft demonstration to date in the United States' history: that day, 597 aircraft flew over the metropolitan area. The New York Times stated that if the aircraft demonstration had not been visible around the city, Floyd Bennett Field's dedication might have attracted more spectators.[60][59]

Commercial use

[edit]

From May 23, 1931, through the end of the year, the airport recorded 1,153 commercial aircraft and 605 military craft, which made a combined 25,000 landings.[61] According to the 1932 Annual Report from the Department of Docks, Floyd Bennett Field had become "the most desirable American Field as an ocean hop terminal": at least four transatlantic flights had occurred there that year, and at least four more flights had been scheduled for 1933.[62] By 1933, Floyd Bennett Field accommodated more flights than Newark Airport: there were 51,828 arrivals and departures at Floyd Bennett Field in 1933, compared to 19,232 at Newark the same year. By number of flights, Floyd Bennett Field was the second-busiest airport in the U.S. that year, behind only Oakland International Airport in California.[63][64]

Floyd Bennett Field was never a commercial success due to its distance from the rest of New York City. Through 1934, there were no commercial passenger airlines that made regular scheduled arrivals or departures at Floyd Bennett Field.[65] This was partly because Floyd Bennett Field was never able to secure a lucrative stream of airmail traffic, which went to Newark Airport instead.[66] According to the 1933 annual report, Newark Airport carried 120,000 airline passengers, 1.5 million pounds (680,000 kg) of mail, and 425,000 pounds (193,000 kg) of express mail, as opposed to Floyd Bennett Field's 52 airline passengers, 98 bags of mail, and 100 pounds (45 kg) of express. According to Tony Wrenn, most of the passenger aircraft and mail planes that landed at Floyd Bennett Field likely only did so because the planes could not land at Newark Airport.[64] In 1937, American Airlines became the only commercial airline that regularly operated at Floyd Bennett Field,[67] and for one specific flight: an air shuttle from New York to Boston.[64] Seaplane taxi routes running from Floyd Bennett Field to piers on the East River at Wall Street and 31st Street were established, but they failed to attract airlines.[67]

As a general aviation airfield, Floyd Bennett Field attracted the record-breaking pilots of the interwar period because of its superior modern facilities, lack of nearby obstacles, and convenient location near the Atlantic Ocean (see § Notable flights).[63][5] The airport hosted dozens of "firsts" and time records as well as a number of air races in its heyday, such as the Bendix Cup.[68] Civilians were also allowed to take flying lessons at Floyd Bennett Field.[69]

Various improvements were made to the airport throughout its entire commercial existence: first as a seaplane hangar, then by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and finally by the United States Navy.[39] However, Floyd Bennett Field's lack of commercial tenants, a byproduct of its isolation from the rest of the city, caused the city to begin developing LaGuardia Field in northern Queens. The new airfield was much closer to Manhattan.[70][66] Commercial aviation activity at Floyd Bennett Field ceased in 1939, when LaGuardia Field (now Airport) was opened.[23] The Navy gained ownership of the field in 1941 after leasing space there for several years.[7][6]

Accessibility

[edit]

Flatbush Avenue was widened and straightened to create a more direct route into Manhattan.[71] In 1937, the avenue was extended south to the Marine Parkway–Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge, which in turn connected to the Rockaways.[72][73] However, this had more to do with the expansion of Marine Park and Jacob Riis Park.[74] The same year, a bus route to the subway, the current Q35 route to the Flatbush Avenue–Brooklyn College station, was established in order to create a faster connection to Manhattan.[75][71] However, the Q35 bus only started making stops at Floyd Bennett Field in 1940.[76]

Floyd Bennett Field's poor location in outer Brooklyn inhibited its usefulness.[69] There were no limited-access roads between Manhattan and the airport, and the only direct route from Manhattan to Floyd Bennett Field was Flatbush Avenue, a congested street with local traffic throughout its length.[63] This was exacerbated by the fact that the bus-to-subway connection did not occur until 1940.[76] The Belt Parkway, which was constructed between 1934 and 1940, provided a limited-access connection to Manhattan for cars. However, commercial traffic could still only use Flatbush Avenue since commercial vehicles were banned from parkways in New York.[74]

Airmail terminal proposals

[edit]During the 1930s, commercial air traffic at airports nationwide was low because few people could afford plane tickets, and airmail made up the majority of air traffic in the United States.[63] Officials believed that "all aviation activity in the New York area" should be located at Floyd Bennett Field.[71] LaGuardia pushed for Floyd Bennett Field to replace Newark Airport in Newark, New Jersey as the city's de facto main air terminal, including designs and plans to shuttle passengers to and from Manhattan in flying boats.[64] However, Newark Airport turned out to be adequately equipped to handle commercial traffic.[77] In the early days of commercial aviation, the bulk of profits was provided by freight instead of passengers. As airmail was a major fraction of air freight at the time, airports having contracts with the United States Post Office Department attracted commercial airlines, and the Post Office Department had already designated Newark Airport as New York City's airmail terminal.[78] In order to try and compete, an expansion of the city's pneumatic tube mail system was planned between Floyd Bennett Field and the main post office in Brooklyn, with a branch of the system continuing to lower Manhattan.[62]

In one well-publicized incident in November 1933, shortly before La Guardia assumed the New York City mayor's office, he refused to get off a plane at Newark Airport because his ticket said that the flight went to New York, and the mayor-elect demanded that the plane be flown to Floyd Bennett Field.[63][79][64] In 1934, officials requested that the Post Office Department compare the merits of Newark Airport and Floyd Bennett Field, as they believed that the latter was better equipped. In letters to Postmaster General James Farley, U.S. Representatives from Brooklyn extolled the new facilities at Floyd Bennett Field and compared them to the inadequate facilities at Newark Airport.[80] However, the representatives failed to note that the Postal Service had chosen Newark Airport because it was built first.[81]

In 1935, La Guardia succeeded in convincing the Post Office Department to review the benefits and drawbacks of Floyd Bennett Field. The department's review of the airport consisted mainly of drawbacks: there was no direct highway or train route from Floyd Bennett Field to Manhattan, but there were such links between Newark and Manhattan.[82] La Guardia suggested that the New York City Subway be extended to Floyd Bennett Field in order to resolve this problem.[83] In August 1935 the department decided to keep the metropolitan area's airline terminal at Newark.[84] However, La Guardia persisted in lobbying for Floyd Bennett Field. He had the New York City Police Department calculate how long it would take, in clear weather, to go from Penn Station to each airport and then back to Penn Station. The NYPD found that it only took 24 minutes to get to or from Newark, but that the same trip to Floyd Bennett Field took 38 minutes.[85] The New York Times determined that it would take five to ten minutes more to go from Midtown Manhattan to Floyd Bennett Field than to Newark.[86] After learning of this evidence, La Guardia then petitioned to make Floyd Bennett Field a suitable alternative to the Newark airmail terminal.[85] To support his argument, La Guardia cited several flights that had been diverted to Floyd Bennett Field.[87]

In December 1935, a meeting was held at the Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, D.C., concerning Floyd Bennett Field's suitability as an airmail terminal.[88] Grover Whalen, chairman of La Guardia's Committee on Airport Development, argued that the city had an "inalienable right" to appear on maps of the United States' airspace, and that Floyd Bennett Field was ready for use as an alternate airmail terminal.[89] In March 1936, Farley announced that he had rejected the bid to move airmail operations to Floyd Bennett Field because all evidence showed that doing so would cause a decline in traffic and profits.[66][90][91]

Ultimately, La Guardia was never able to convince the Postal Service to move its New York City operations from Newark to Floyd Bennett Field.[66] Because airmail traffic did not move to Floyd Bennett Field, neither did most of the commercial lines, save for American Airlines flights to Boston.[64] Instead, he decided to allow the city to construct LaGuardia Airport in Queens.[70][66] The new airport was much closer to Manhattan, and it took advantage of the then-new Queens-Midtown Tunnel.[70] Moreover, the federal government created a new airmail contract in which it divided airmail traffic between Newark Airport and LaGuardia Airport once the latter was completed. This confirmed that Floyd Bennett Field was denied an airmail contract not in spite of being located in New York City, but because it was too far from Manhattan.[92]

Military and police activity

[edit]

After the 1930 closure of Naval Air Station Rockaway across Rockaway Inlet, a hangar at Floyd Bennett Field was dedicated as Naval Air Reserve Base New York within the larger civilian facility. The Naval Reserve Aviation Unit started using Floyd Bennett Field in April 1931, when it moved from Long Island's Curtiss Field to Hangar 1 in Floyd Bennett Field, leasing the hangar for $1 per year. The Department of Docks allowed the Navy to use the airport's other facilities as needed, but left the Navy to pay for any additional expenses on its own.[61] The unit soon moved to Hangar 5 because they required more space.[63][93][56]

Starting in 1934,[94] the NYPD also occupied a hangar for the world's first police aviation unit.[95] The NYPD Aviation Unit occupied Hangar 4.[63]

In 1935, the United States Coast Guard wrote a letter to the city requesting that part of Floyd Bennett Field be set aside for Coast Guard use.[96] In 1936, a 650-by-650-foot (200 by 200 m) square parcel of Floyd Bennett Field along Jamaica Bay, covering an approximately 10-acre (4.0 ha) area, was leased to the Coast Guard for the creation of Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn (CGAS Brooklyn).[95][97][98] In February 1937, the Graves-Quinn Corporation was hired to create a hangar, barracks building, garages, and "other support facilities" for the new Coast Guard station.[99][100] The $1 million facility opened in June 1938.[101][102] At the time, the Coast Guard was only paying $1 per year in rent, which was insufficient in light of Floyd Bennett Field's commercial troubles.[100]

The Navy expanded in 1937 and again in 1939 (see § Improvements).[93] The Navy wished to further expand its presence in Floyd Bennett Field, and in June 1940, the government started a third, $1 million expansion of the naval facilities there.[103] It built barracks for 125 Naval Reserve cadets, expanded Hangar 2,[103] and took over Hangars 3 and 4.[93] The Navy agreed to rent the expanded complex for $8,000 per year, effective October 1.[104] However, by August 1940, the Navy was considering purchasing the entire airport.[105][106] The city valued Floyd Bennett Field at $15 million, but was at first uncertain about whether to sell the airport.[107] The city wanted to retain control of the airport because the NYPD base was housed there. La Guardia also felt that the federal government might buy the airport for less than the assessed price of $15 million because it had already paid for improvements.[104]

Throughout this time, World War II's European theater was growing in intensity.[104] In December 1940, while the Navy and the city were in negotiations about the proposed sale of Floyd Bennett Field, the Navy pilot Eddie August Schneider died in a training crash on the tarmac, together with another pilot whom he was training.[108]

A security survey, conducted in spring 1941, weighed the benefits and drawbacks of Floyd Bennett Field. The benefit was that the Navy already had a base there, but the drawback was that it was going to be too hard to manage both military and civilian traffic at the same airport.[105] The solution was to close the airport to all civilian uses (see § World War II).[109] Soon after the survey was conducted, the city suggested that the Navy take an 8-year lease on the airport, while the Coast Guard continued to lease its own hangar.[110][109]

Improvements

[edit]

Improvements to Floyd Bennett Field continued even after its second dedication.[77] A study from the State University of New York lists four phases of construction through 1941, including three phases after the airport's opening. The first additional phase, between 1932 and 1933, covers the completion of the seaplane facilities at Floyd Bennett Field. A second phase from 1934 to 1938 covers improvements WPA, while a third phase includes additions by the United States Navy between 1939 and 1941.[39]

A vehicle parking area was completed in May 1931, and the Administration Building was opened in October of the same year. New taxiways and a temporary wire fence were completed in 1932. That year, contracts for repairing the hangars' roofs and grading the land were also awarded.[111] Floyd Bennett Field did not yet have an A1A rating, so the city gave a contract to the General Electric Company to install lights along the runways; lighted directional signs on the roofs of three hangars; and wind-recording equipment. A local company, the Sperry Gyroscope Company, was contracted to install two 28-foot-tall (8.5 m) floodlight towers around the field. An electrical wiring system was built around the airport, and two accompanying buildings hosting a transformer and sewage pump were built alongside it.[112][113] The other maintenance facilities were not added until later. A gravel parking area with two entrance driveways, as well as a separator fence between the parking area and the runways, was completed in 1932. Three taxiways, each 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, were constructed in order to reduce congestion from planes who were lining up to take off.[114][115]

A seaplane base was also constructed as part of the first additional phase of construction. It had been part of the original plans for the airport, but only a steel bulkhead had been constructed.[116] During the initial construction phase, seaplane ramps had been built on the east side of the airport.[14] The contract for a seaplane base with four hangars[65] was awarded in 1930 and completed in October 1931.[111] The city had finished building a 220-foot-long (67 m) by 50-foot-wide (15 m) seaplane ramp by August 1931. It was accompanied by a 480-foot-long (150 m) by 30-foot-wide (9.1 m) seaplane pier and three anchorage buoys.[116] Three seaplane runways were built, as well as a turning basin.[65]

Spurred by the expansion of air travel across the United States, the Department of Docks began planning extensive upgrades to Floyd Bennett Field in 1934. The plans coincided with the authorization of the WPA, which provided the labor needed to carry out these upgrades.[117] In 1935, the WPA allocated $1.5 million to finish the airport.[118] The federal government ultimately contributed $4.7 million toward Floyd Bennett Field's expansion, while the city spent only slightly more than $339,000. The WPA constructed two extra runways; expanded hangars and airport aprons; erected extra maintenance buildings; added a passenger tunnel under the administration building; and placed utility wires and pipes underground.[119][117] The WPA also planted a landscaped lawn in front of the administration building.[120] The work involved the demolition of a brick chimney at the south end of Barren Island, which lay in the way of one of the new runways.[121]

There were plans to add four more hangars and two more ramps to the existing seaplane base, but they were not acted upon due to low passenger traffic volumes.[65] The expanded seaplane base was also in the path of Runway 12–30, which was added as part of the WPA renovations.[122] Because the base was not going to be expanded, the Coast Guard started using the unfinished seaplane base for their own purposes.[122][42] The Coast Guard added a new hangar, a taxiway, and three radio towers.[123]

The Navy, which already occupied part of Floyd Bennett Field, unveiled plans to expand its facilities there in 1938. The next year, the timeline was moved up due to World War II in Europe.[70] In 1939, the Navy started constructing a base for 24 seaplanes at Floyd Bennett Field, in preparation for expanding its "neutrality patrol" activities during World War II.[124][125] After its 1939 expansion, the Navy occupied Hangars 1 and 2; the new Building A in between Hangars 1 and 2; and half of the field's "Dope Shop".[93] In January 1940, Congress approved the Navy's request to take over ownership of 16.4 acres (6.6 ha) in Floyd Bennett Field so it could construct a new base.[126] Like the Coast Guard, the Navy would lease the land for $1 per year, but if the Navy stopped using their facilities at Floyd Bennett Field, the Navy base's ownership would revert to the New York City government.[127]

Naval Air Station New York

[edit]

Acquisition

[edit]Changes to the Navy's expansion plan were announced on May 25, 1941. As part of the plan, all private airlines were ordered to leave, and all remaining residents on Barren Island would be evicted to make way for a larger facility.[109] On May 26, 1941, the airport was closed to all commercial and general aviation uses.[128] A week later, on June 2, the Navy opened Naval Air Station New York (NAS New York) with an air show that attracted 30,000[7] to 50,000 attendees.[6][129] The audience included Navy undersecretary James Forrestal; Admiral Harold R. Stark; Rear Admiral Clark H. Woodward, commandant of the Brooklyn Navy Yard; Rear Admiral Chester W. Nimitz; Rear Admiral John H. Towers; New York City mayor La Guardia, and Brooklyn borough president John Cashmore.[7][129]

By fall 1941, the Navy decided that Floyd Bennett Field was the best place to put its air station in New York. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Navy sought to acquire the property, as well as surrounding land, as soon as possible.[110] Artemus Gates, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air, wrote a letter to La Guardia stating that the Navy was willing to take over control of Floyd Bennett Field for a price of $9.75 million.[129][110] This offer was substantially less than La Guardia's asking price of $15 million,[110][107] and it took into account the valuation of the WPA improvements and existing military facilities.[130] On February 9, 1942, the Navy submitted a "declaration of taking" that would allow it to acquire most of the desired land for $9.25 million.[131] Nine days later, on February 18, the rest of Floyd Bennett Field became part of NAS New York.[129] Most prior leases were terminated, but the Coast Guard was allowed to stay if its operations did not conflict with the Navy's.[131][23] This meant that the NYPD aviation unit at Floyd Bennett Field was forced to relocate for the duration of the war.[94]

The expanded naval base totaled over 1,280 acres (520 ha). This consisted of 993 acres (402 ha) of the existing airfield; the combined 34 acres (14 ha) that belonged to the Coast Guard and Navy; and the combined 92 acres (37 ha) that belonged to the remaining Barren Island residents.[110] The Navy had also wanted to buy 171 acres (69 ha) on the west side of Flatbush Avenue,[131] which was reserved for a future expansion of Marine Park.[110][132] However, New York City Parks Department Commissioner Robert Moses prevented the purchase from happening.[132] Some of the money from the transaction was to go toward improving Marine Park.[133]

World War II

[edit]

The Navy awarded the first contract for upgrades to Floyd Bennett Field on December 17, 1941.[134] The Navy's Design Division developed most of the expansion plans instead of contracting them out.[135] It graded the undeveloped land to 16 feet to make it level with the rest of the airport.[136][137] Demolition of the future barracks site on the western side of the field started in spring 1941.[109][138][137] Because newer craft necessitated longer runways,[134] a new Runway 6–24 was built on the northern side of the field, and three existing runways were expanded so that all four runways measured 5,000 feet (1,500 m) long by 300 feet (91 m) wide. The Navy built a seaplane hangar and two seaplane runways, as well as extended the taxiways and roads. It also constructed facilities for officers on Floyd Bennett Field's eastern side, such as barracks, training rooms, dining rooms, and auditoriums.[139][132][137] The Navy also filled in the northeastern section of the former Barren Island.[140][137] A new entrance for the Navy was created at the south end of Floyd Bennett Field,[141][137] and a one-story annex on the north side of the Administration Building was added.[142][137] A dirigible landing station and two front-line simulator facilities were installed within the field.[143][137] Significant effort was spent toward developing the part of the base that faced Jamaica Bay, where a recreation area was installed.[144][137] All remnants of Barren Island's former community and landscape were obliterated.[145][137]

The upgrades allowed 6,500 people to use the naval base.[134] Most of the new structures were designed to be removable because of the possibility that Floyd Bennett Field might become a civilian airfield again after the war.[135] In accordance with military conventions, all the buildings at Floyd Bennett Field were given numbers.[140]

During the war, NAS New York hosted several naval aviation units of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, including three land-based antisubmarine patrol squadrons, a scout observation service unit, and two Naval Air Transport Service (NATS) squadrons (processing the majority of the aircraft destined for the Pacific Theater).[146] NAS New York served as a training facility, as well as a base where Navy boats could load supplies and officers. NAS New York aircraft also patrolled the Atlantic coastline and engaged German U-boats.[129] In addition, Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) took up several positions, including those of air traffic controllers, parachute riggers, and aviation machinist's mates.[147][148] The Military Air Transport Service opened an East Coast terminal at Floyd Bennett Field in December 1943.[149] More than 20,000 new aircraft were delivered to NAS New York during the war, and more than 46,000 aircraft movements were recorded from December 1943 to November 1945.[14]

CGAS Brooklyn worked in conjunction with NAS New York, patrolling New York Harbor as well as testing equipment, training soldiers, and delivering supplies.[150] Starting in 1944, CGAS Brooklyn tested Navy craft and trained the pilots.[150][151]

Korean to Vietnam Wars

[edit]In 1946, after the conclusion of World War II, many naval stations were decommissioned or downgraded.[152][153] As part of these cutbacks, Floyd Bennett Field became a Naval Air Reserve station.[149][152] At the time, it was the largest Naval Air Reserve base in the U.S.[154] The Navy demolished many of the temporary structures, including the barracks, as well as the outdated Sperry floodlights. The Navy renovated the recreation field on the southern side of Floyd Bennett Field.[155] The NYPD Aviation Unit resumed its operations at the Naval Air Reserve base.[155][94]

By 1947, there were proposals to use Floyd Bennett Field for commercial purposes again. The airport would have handled the excess traffic from LaGuardia Airport while LaGuardia was being repaired and Idlewild (now JFK) Airport was being built.[149] In April 1947, the city and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey made a preliminary agreement that allowed the Port Authority to take over operations of all airports in New York City by June.[156] The Port Authority hoped to spend $1.5 million to improve facilities for airlines with foreign registrations.[157] However, the partial conversion of Floyd Bennett Field commercial use was delayed over concerns of cost: the Navy estimated that it would cost $1.2 million to move its facilities, but the Port Authority would not spend more than $750,000 for the Navy to do this.[158] The Navy mostly operated on the southern and eastern parts of the airport during this time.[149] By September 1947, the Port Authority and the Navy were deadlocked, unable to reach an agreement.[159] Commercial traffic at Floyd Bennett Field ultimately never materialized, as the airspace congestion near LaGuardia Airport was resolved.[160]

The Navy allowed New York Air National Guard and the U.S. Army Air Reserve to use the hangars on the condition that their activities did not interfere with the Navy's.[155][161] The Coast Guard regained control of CGAS Brooklyn, and it also began leasing nearly 2 acres (0.81 ha) of the Navy base adjoining CGAS Brooklyn's southern border.[162] By 1950, Cold War and Korean War preparations were underway,[153] and the Navy needed to use Floyd Bennett Field's facilities again.[160][162] However, Floyd Bennett Field was less busy during the Korean War than during World War II.[163] Five reserve squadrons based at Floyd Bennett Field were recalled to active duty for the Korean War.[160] Some minor modifications were made during this time. The Navy lengthened three runways, reconstructed roads and taxiways, built a beacon tower and veterans' housing, and added some fuel storage containers. A new southern entrance was built because one of the runway extensions overlapped with the old entrance.[163][164] The Navy abandoned many of the original buildings on the western side of the field, instead moving to the eastern side.[165] The Coast Guard made even fewer modifications: it expanded its apron, built a small hangar, and replaced its wooden seaplane ramp with a concrete one.[166]

Throughout the remainder of the postwar period and until the early 1970s, NAS New York-Floyd Bennett Field primarily functioned as a support base for units of the Naval Air Reserve and the Marine Air Reserve.[149] The airport was also a training facility for reserve squadrons. Until 1970, more than 3,000 reservists in the Navy and Marines trained at Floyd Bennett Field every weekend, and 34 aircraft squadrons were constantly being maintained at the field.[163][160] The field was busiest during the weekends when there were up to 300 daily departures from Floyd Bennett Field.[167][8] The installation also served as a base for units of the New York Air National Guard from 1947 to 1970, when the Air National Guard moved to the Francis S. Gabreski Air National Guard Base on Long Island.[154] Minor adjustments were made to the field through the 1960s in order to accommodate jet aircraft.[167] The Navy also built a trailer park and a school building in the main barracks area during this time.[168][169]

Decommissioning

[edit]During the height of the Vietnam War in the late 1960s, military budgets were strained by a combination of combat operations in Southeast Asia and funding constraints due to President Lyndon Johnson's concurrent Great Society programs. This necessitated all the services, but especially the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force, to reduce stateside installation infrastructure.[160] By 1970, the Navy was offloading property, including NAS New York / Floyd Bennett Field, to pay for the war's expenses.[170][154]

On March 5, 1970, the federal government announced that the Navy would start vacating the military portion of the airport and close the operational airfield. Upon the announcement of NAS New York / Floyd Bennett Field's decommissioning, Mayor John V. Lindsay asked the federal government for permission to convert the field into a commercial airport.[171] Simultaneously, Governor Nelson Rockefeller proposed a $1.4 billion development on the site. If built, Rockefeller's development would contain a shopping mall, an industrial park, 46,100 housing units, and the potential for 180,000 residents.[172][173] The governor's proposal had been in planning since November 1969.[172][160]

On April 4, 1970, the Navy conducted its last daily formal inspections, an act that started the process of decommissioning NAS New York / Floyd Bennett Field. NAS New York's tenant squadrons and units and personnel were transferred to other naval air stations.[170][8] A Naval Air Reserve Detachment, which supported non-flying units, remained as Naval Air Reserve New York / Naval Reserve Center New York.[174] The Navy itself continued to own the land for two more years.[175][176] The Naval Air Reserve Detachment would occupy Hangar A until 1983.[177]

Meanwhile, the dispute over the possible future uses of Floyd Bennett Field continued. In May 1970, the state government released more details of its redevelopment proposal without consulting the city.[178] The next month, Lindsay's administration wrote to the federal government, advocating for Floyd Bennett Field to be converted to commercial use.[179] U.S. President Richard Nixon supported a third proposal: turning the entirety of Floyd Bennett Field into a national park.[180] This had been suggested by the Regional Plan Association (RPA) the previous year, except that the RPA had advocated for a national seashore.[181][173] In May, the president started the process of getting Congressional approval for this move.[180] The state government objected, since the neighboring Marine Park was not used.[182] In the meantime, Floyd Bennett Field was only sparsely used by Coast Guard and NYPD helicopters.[183]

National Park Service stewardship

[edit]Creation and early years

[edit]

The United States House of Representatives approved the creation of Gateway National Recreation Area in September 1972, and most of the land was transferred to the National Park Service (NPS) for inclusion in Gateway National Recreation Area. In the same vote, the House denied the state's provision to create a housing development at Floyd Bennett Field.[176] The recreation area was officially created on October 27, 1972.[184] The National Park Service acquired most of the Navy-owned portion of the field, as well as some city-owned land to the west and north that had not been owned by the Navy. Floyd Bennett Field became the headquarters for the Gateway Area's Jamaica Bay unit.[185][186] The Coast Guard was able to gain ownership of CGAS Brooklyn, which it then proceeded to expand. In circa 1973, new concrete barracks were erected on the site of the former World War II-era barracks.[187][188] The remainder of Floyd Bennett Field was owned separately by the Naval Air Reserve Detachment, as well as the United States Department of the Interior (the NPS' parent agency) and the United States Department of Transportation (the Coast Guard's parent agency).[186] The NYPD's aviation unit continued to lease space in hangar 3, and later also started leasing hangar 4.[189]

The park opened in 1974.[9] Most of the National Park Service's early actions regarding Floyd Bennett Field focused on promoting recreational activities. Due to a lack of funds, the NPS let much of the physical field revert to its natural state.[190] The NPS added tents in two areas of Floyd Bennett Field, which it then designated as campgrounds. Around 1974, the NPS also planted pine trees near the field's southern boundary, forming the current "Ecology Village".[9] By 1979, the NPS had developed a "General Management Plan" for the entire Gateway Area. The plan allowed for Floyd Bennett Field to be divided into three management zones: the "Natural Area", the "Developed Area", and the "Administrative Area". It also created the new William Fitts Ryan Visitor Center within the former administration building.[191] In 1980, many of the airport's structures were listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[1][154]

In its early years as a park, Floyd Bennett Field had very few visitors. According to a 1991 estimate, about 30 people visited the park on an average day. The field's chief park ranger at the time attributed the low visitor count to several factors, including "the chain-link fence along Flatbush Avenue, the Coast Guard station and the guardhouse". The park was relatively unknown even to people who lived nearby.[192]

1990s

[edit]In 1988, the NPS started seeking plans for private developments at Floyd Bennett Field. Many of these plans, including those for condominium housing and an amusement park, were dismissed. By the 1990s, the NPS began looking for commercial tenants to occupy the deteriorating hangars.[192] In approximately 1996, Floyd Bennett Field received an allocation of funds, which it used to improve parking access in front of the Ryan Center.[193]

In 1997, the 6th Communication Battalion of the United States Marine Corps Reserve moved onto the south side of Floyd Bennett Field.[194] The next year, CGAS Brooklyn was decommissioned following its merger with CGAS Cape May, New Jersey, and relocation to the new Coast Guard Air Station Atlantic City, New Jersey. The majority of former Coast Guard land then transferred to the National Park Service.[195]: 33 A small portion remained in the possession of the Coast Guard's parent agency at the time, U.S. Department of Transportation, so the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) could use it.[189][195]: 33 The NYPD moved their aviation operation from a hangar to the former Coast Guard Air Station facilities shortly afterward, under agreement with the NPS.[189] The New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) also moved into Floyd Bennett Field by the late 1990s, using the runways as a location for truck-driving practice.[177][196]

In 1999, a 119-foot-tall (36 m) Doppler radar tower for recording wind shears was placed at Floyd Bennett Field for use by nearby JFK Airport.[197] The $6 million tower was controversial, as residents protested that the tower was visually unattractive.[198] In September 1999, the Department of the Interior granted the FAA permission to erect the radar at Floyd Bennett Field on the condition that the radar be torn down in 20 years. If a less disruptive radar was developed before then, the tower at Floyd Bennett Field had to be torn down.[197] The Interior Department disliked the radar's placement within Floyd Bennett Field, but allowed the FAA to build the radar within the NYPD heliport, which had "no recreational value". At the time, JFK Airport was the last major airport in the United States to receive a wind shear radar.[199] Attempts at building the radar dated to 1993,[200] but were delayed because Long Island residents and U.S. Senator Al D'Amato opposed it.[199]

21st century

[edit]The NPS issued a request for proposals for the hangars in 2001 and received two bids, both of which contained an ice skating rink. A company named Aviator submitted the winning bid.[201] In 2006, hangars 1 through 4 were adapted for reuse and leased as a business concession to the Aviator Sports and Events Center, a community-based sports and entertainment complex.[202]: 4 [203] The site of hangars 9 and 10 was also redeveloped as part of the Aviator Complex.[204] Since the opening of the Aviator Sports Complex, there have been other plans to renovate Floyd Bennett Field. These range from grandiose plans, such as an Olympic-size swimming pool or drive-in theater, to regular upkeep, such as clearer signs and transportation across the airport.[205] By the early 2000s, Ryan Center was being rehabilitated to its original state.[204] In 2010, work started on the restoration of the building.[205] The renovation was completed in May 2012.[206][207]

During the 21st century, Floyd Bennett Field has been used for dealing with the aftermath of disasters. After the crash of American Airlines Flight 587 into Belle Harbor in the nearby Rockaway Peninsula on November 12, 2001, one of Floyd Bennett Field's hangars was used as a makeshift morgue for the crash victims.[208] In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in October and November 2012, a portion of one runway was used as a staging area by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, for relief workers who were conducting rescues and evacuations in the Rockaways.[209]

In July 2011, U.S. Representative Michael G. Grimm introduced H.R. 2606 – New York City Natural Gas Supply Enhancement Act, which would convert one of Floyd Bennett Field's hangars to a gas meter station for a proposed natural gas pipeline through New York City.[210] The Williams Company was to restore that hangar for pipeline use.[211] In 2015, U.S. Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand announced that a bill with a $2.4 million upgrade for the New York State Marine Corps Reserve complex in Brooklyn had passed in the U.S. Congress.[194] The next year, Gillibrand obtained $15.1 million in funding to renovate two Marine Corps Reserve facilities, including the 6th Communications Battalion, which needed $1.9 million to replace electrical duct banks.[212]

Nonprofit organization Jamaica Bay-Rockaway Parks Conservancy presented plans to the Brooklyn Community Board 18 in April 2023 for the restoration of three structures at Floyd Bennett Field.[213] The same year, a charter school in Brooklyn announced plans to construct a sustainability-themed school at Floyd Bennett Field for $60 million.[214][215] In August 2023, state and federal officials reached an agreement to build a large shelter for migrants at Floyd Bennett Field, amid a citywide migrant housing crisis caused by a sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers traveling to the city.[216] The shelter opened that November, but its remote location deterred many migrants.[217]

Description

[edit]

Floyd Bennett Field is located on a plot of more than 1,000 acres (400 ha)[202] in southeastern Brooklyn, on the western end of Long Island. It is about 20 miles (32 km) from Midtown Manhattan.[218] The field itself is located on the eastern side of Flatbush Avenue along the northern coast of Rockaway Inlet. However, the National Park Service administers land on both sides of the Avenue.[202]: 3 [10]

The section east of Flatbush Avenue, comprising the original airport, consists of the airfield's eight hangars, an administration building, and five runways.[219][202]: 3 [10] These structures have largely been preserved in their original state, as opposed to most municipal airports, which have been upgraded.[220] Two runways and two taxiways surround a large "field" that is crossed by the three other runways.[10] The North Forty Natural Area is located between the field to the south and the Belt Parkway to the north.[202]: 3 [10] The eastern coast is adjoined by Mill Basin Inlet to the north and Jamaica Bay to the east.[10] The Gateway Development Plan of 1979 divides the field in three areas. The "Natural Area", on the northern side of the field, was intended for ecological preservation. The "Developed Area", comprising the hangars and administration buildings on the western side of the field, was supposed to be for structural preservation and reuse. Finally, the "Administrative Area" was made up of the structures on the southern side of the field that were still in use by the Coast Guard, the Departments of the Interior and Transportation, and the New York Police Department.[191]

The part of the National Park west of Flatbush Avenue includes a golf driving range and marina.[202]: 3 [10] It is bordered by Dead Horse Bay to the west.[10]

Floyd Bennett Field also accommodates public camping, with 46 campsites located on the east side of the field.[221] A "Grassland Management Area" in the center of the field, near the intersection of three of the runways, is closed to the public. An "Ecology Village" for classes of middle-school students is located at the south end of the field.[202]: 3 [10] South of the field, there is also an archery range; a softball field for Poly Tech; a baseball field for Poly Tech; and a racetrack for remote-controlled cars.[10] The New York City Police Department (NYPD), New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY), and United States Park Police (USPP) all have their own plots of land on the eastern side of Floyd Bennett Field.[202]: 4

The IATA airport code and Federal Aviation Administration airfield identifier code was NOP when it was an operational naval air station and later Coast Guard air station,[222] but now uses the FAA Location Identifier NY22 for the heliport operated there by the NYPD.[223]

Administration Building

[edit]

The administration building (now the William Fitts Ryan Visitor Center, or Ryan Center[224]) is a two-story neo-Georgian building set back from Flatbush Avenue with a four-story observation tower.[225][219] Ryan Center, which is named after U.S. Representative William Fitts Ryan, serves as the entrance to Floyd Bennett Field,[202]: 15 and formerly also served as the airport's passenger terminal and administration building.[14] Ryan Center is partially accessible to the public, including guided visits to the former control tower.[226]

Ryan Center is a rectangular building measuring 185 by 72 feet (56 by 22 m), with the longer side running parallel to Flatbush Avenue.[219] The facade is made of red and black brick.[14][227] The building has a brick parapet that juts out above its entablature. It also has quoins, a foundation, and a water table made of white stone.[225][227][56] The neoclassical details of the building, which can also be found in train stations and post offices built in the early 20th century, were purposely included to give passengers a familiar feeling. At the time, flying was still largely untested and relatively few people had ever flown.[56]

The western and eastern elevations are composed of three parts, of which the center portions on both facades project outward. On the west side, which faces Flatbush Avenue, the center portion of the facade consists of an entrance with three recessed bays; the two smaller bays on the sides flank a wider and taller central bay. The bays comprise a symmetrical portico with supporting Ionic columns. As built, a polychrome winged globe, part of the original design, was located at the corner of the portico. A Naval Air Station clock hung above each of the three doorways.[227][225] The west side of the administration building also contained entrance ramps for passengers, which led to baggage ramps on the east side of the building. During the WPA renovations, the baggage ramps were replaced with four tunnels that allowed passengers to cross under the runways.[14][119]

On the eastern facade, the center portion is shaped like three sides of an octagon. This semi-octagonal-section contains the four-story observation tower; the lower three stories have the same brick facade as the rest of the building, while the former control tower on the top floor contains a steel frame.[227][56] The control tower was added after the rest of the administration complex had been completed.[224] On the left and right sides of the eastern elevation's central portion, there are balconies on the first floor with stone balusters.[227] Bronze letters spelling "Naval Air Station" and "Floyd Bennett Field" are located over the east-side facade's entablature.[225] Before the tunnels were added during the WPA renovations, passengers exiting out the eastern side of the building would descend to the airport apron, where they could board planes from ground level.[56] A one-story annex on the northern side of the building was added in 1941.[142]

The interior is designed in the Art Deco style.[14] Originally, the administration building contained a restaurant, cafeteria, post office, dormitories, and visitor's lounge. There were also rooms for the National Weather Service and the United States Department of Commerce.[225][54] It is sparsely ornamented with occasional marble panels.[225]

A parking area was added to the western side of the administration building in 1932. It was a gravel lot that could be accessed by two driveways extending diagonally from Flatbush Avenue.[114][115] A landscaped garden was added to the front of the administration building from 1935 to 1936. Shrubs and flower beds were placed in front of the Administration Building. A footpath from Flatbush Avenue to the building's main entrance, with a circular section in the middle, was built through the front lawn. A flagpole and a park-like entrance sign was placed within the circular part of the sidewalk.[120] Since the front lawn had formerly housed refreshment stands, a one-story refreshment building was erected to the north of the administration building. Two parking facilities were also constructed north of the administration building, near the more northerly set of hangars.[228] During World War II, the driveways and parking lot were fenced off, and all visitors used the field's southern entrance on Aviation Road.[141]

A community garden exists south of Ryan Center.[10][205][224] With approximately 480 plots, it is the largest community garden in New York City.[229][230] The Floyd Bennett Garden Association oversees the gardens' management.[231]

Hangars

[edit]

Along Hangar Row

[edit]The original hangars, which are numbered, are located on the south side of the airfield near Flatbush Avenue in what is known as "Hangar Row".[52] Hangars 1–4 were built on the north side of the administration building, while hangars 5–8 were built on the south side.[14] Each set of four hangars is laid out in a 2×2 setup, with both pairs of hangars in each set facing each other. The hangars are of virtually identical design.[232] The structures contain buff-and-brown glazed brick facades with steel frames and steel truss ceilings, and they also originally had aluminum doors.[227][52] Outside each hangar is a two-story 20-by-140-foot (6.1 by 42.7 m) service wing with buff brick facades and steel-framed windows and doors.[232][52] The letters on the parapets above each hangar spelled "City of New York" and "Floyd Bennett Field".[52]

Each pair of hangars is connected by a buff brick structure, which housed offices, utilities, and shops. The hangars were constructed in 1929–1931 while the structures between each pair of hangars were constructed during the WPA renovations in 1936–1938.[232][67][227] The four pairs of hangars were built in numerically ascending order from north to south: the northernmost hangars are numbered 1 and 2, while the southernmost hangars are numbered 7 and 8.[233] The hangars, their connecting structures, and their service wings contained varying levels of Art Deco decoration on their exteriors.[225] Each of the original eight hangars had a 120-by-140-foot (37 by 43 m) interior space,[69][219] and their doors were 22 feet (6.7 m) tall.[232][219] Each of the hangars were created with 80,000 bricks and 250 tons of steel.[219] The hangars were supported by 250 precast deep concrete foundations, each 45 feet (14 m) deep with 14 inches (36 cm) square bases.[232][219]

By 1942–1943, the Navy had also built hangars 9 and 10, two wood-frame structures, to the north of Hangars 1 and 2.[234] Hangar 9 was the first of the pair to be constructed, followed by Hangar 10 a year later. Both had barrel-vaulted roofs and two-story brick extensions to the east.[235]

In 2006, hangars 5–8 were combined to form the Aviator Sports and Events Center,[224] a $38 million recreational complex. The Aviator Complex contains ice skating rinks within two of the hangars. The other two hangars contain a field house, a gymnastics and dance complex, and a fitness center totaling more than 48,000 square feet (4,500 m2). The Aviator Complex also has several restaurants and stores, as well as two turf football fields outside.[201][203] The two fields were developed on the sites of hangars 9 and 10.[204]

Along the coast

[edit]

In 1937, the Coast Guard built a hangar on the Jamaica Bay coast, near the southeastern end of Runway 30. The hangar was built in the Moderne architectural style with white stucco-and-concrete walls, glazed sliding doors, a barrel vault-shaped roof, and a bas-relief of Coast Guard insignia above the doors. Its interior measures 161 by 182 feet (49 by 55 m), and a concrete apron is located outside of the hangar. There is a two-story office wing on the north side of the hangar, as well as one-story attachments to both the west and east. There were also three 30-foot-tall (9.1 m) radio communication towers to the north of the hangar.[123] The Coast Guard occupied the hangar until around 1998.[195]: 33

In 1939, the Navy started construction on the first of two planned hangars along the Jamaica Bay coast. The $600,000 steel-framed Hangar A, which was built to house the Navy's flying boats, contains a steel frame and glazed sliding doors to the north and south. Its dimensions are 250 by 400 feet (76 by 122 m), making it five times as large as hangars 1–8 and three times as large as the Coast Guard Hangar. There are one-story attachments to the west and east.[136][109] The facade was austere, with no architectural embellishments.[136] A seaplane ramp, wooden pier, and access road were also built along with the new hangar.[138]

In 1942, construction started on the second planned hangar, which was labeled Hangar B. The second hangar was an exact duplicate of Hangar A, and it was located to Hangar A's north. In conjunction with this new addition, the Navy also built Seaplane Ramp B.[236] Both hangars were modified to accommodate jet airplanes during the Cold War in the 1950s.[237][169]

Hangar A was demolished in 1998 when DSNY started occupying part of the former Navy site.[177] Volunteers from the Historic Aircraft Restoration Project maintain a collection of aircraft in Hangar B. These planes are similar to those that were historically used at the airfield.[224][238][239]

Additional buildings

[edit]Originally, all of the maintenance functions were hosted inside the Administration Building, but they later got their own buildings.[115] Many of these buildings were added from 1934 to 1938 as part of the WPA renovation.[117] The maintenance buildings have similar designs to the original eight hangars.[52] A brick service building and a generator building originally faced hangars 1 and 2, while a pump house and generator building were built near hangars 5 and 6.[233] A one-story garage and maintenance shop was built at the airport's southwest corner along Flatbush Avenue, south of the hangars. East of the garage, there were two small one-story structures that served as an electrical closet and a pump house. Additionally, a one-story transformer building was located north of the hangars. Two one-story buildings for fire and gasoline pumps are located to the west of Ryan Center.[240]

The Navy also built several wood-frame structures during World War II, south of the hangars. Their facades were made of white clapboards, and they had gable or hipped roofs with narrow windows.[235] A munitions storage complex was developed at the north end of the field around the same time.[145] Although most of the original structures remain intact, the garage building and the field house were demolished by the Navy in 1941 and 1964, respectively.[241] The Navy stopped using many of these structures after World War II.[165]

During World War II, the Navy built two barracks areas on the southwestern side of the field. The west barracks area comprised two barracks, while the main barracks area was larger.[242] The main barracks also comprised two barracks: an H-shaped building for enlisted officers and a T-shaped building for bachelor officers.[138] However, it also had a mess hall, recreation building, and central square.[243] South of the barracks was a sewage treatment plant.[242] The main barracks were demolished after World War II and were replaced with more permanent barracks areas, which housed veterans.[237][169] In the 1960s, the Navy built three ranch houses along the coast, which were intended for a planned Armed Forces Reserve Center. The Navy demolished the veterans' barracks and replaced them with a trailer park containing 24 courts for mobile homes. A three-story school building was built in this area in 1967.[168][169] In 1970, the Navy demolished the barracks south of Hangar A and completed a new barracks, which was named Tylunas Hall after the late Navy commander John F. Tylunas.[175] Tylunas Hall is now used by the DSNY.[177]

The Coast Guard also constructed frame barracks in 1943 and closed them by 1972. A new concrete barracks was completed in 1979.[188] In 1979, the Coast Guard built a swimming pool on the site of its former barracks.[177]

Runways

[edit]

Floyd Bennett Field contains five concrete runways.[42][43][244] Two were laid in 1929,[224] while another two were constructed during the WPA Renovation Project in 1937–1938.[117] Another runway was built in 1942, after the airport was transferred to Navy operation.[244] During the WPA renovations, four turntables were installed to allow planes to turn around quickly.[14][245] The runways have long since been closed to air traffic. Modern visitors use the runways for flying radio-controlled aircraft, land sailing, and cycling.[202]: 3 [224] The end of Runway 19 contains an area where visitors can fly model airplanes.[10][224][231] As per International Civil Aviation Organization standards, the runways were numbered based on their alignment: the value on each end was how many tens of degrees off that runway was from facing magnetic north, counting in the clockwise direction and rounding to the nearest whole number. For example, a plane landing on Runway 19 would be facing slightly magnetic southwest since it would be 190 degrees clockwise from magnetic north, while a plane landing on one of the two Runways 6 would be facing magnetic northeast since it would be 60 degrees clockwise from magnetic north.[246]

The two original runways are 100 feet (30 m) wide. The 3,100-foot (940 m) Runway 15–33[49] was lengthened to 3,500 feet (1,100 m) in 1936.[44] It runs parallel to the original hangars along Flatbush Avenue.[225] Old Runway 6–24 was the longer of the two runways, with a length of 4,000-foot (1,200 m), and ran perpendicular to the original hangars.[49][225] After the WPA renovations in the mid-1930s, the ends of Runway 15–33 were equipped with green runway lights, and that runway was designated as the "blind landing runway" for bad-weather or nighttime landings.[247][241]

The two runways constructed in 1937–1938 are 150 feet (46 m) wide. Runway 1–19 was originally 3,500-foot (1,100 m) long. It ran from the vicinity of the current main public entrance to the field at the south end of Flatbush Avenue, to the North corner of the field near the Mill Basin Inlet.[119][228][240] Runway 12–30 was originally 3,200-foot (980 m) long. It ran from the former Coast Guard Hangar to the Northwest corner of the field near Flatbush Avenue.[248][228][240] A brick chimney near Runway 12 was demolished because it was in the way of the flight path.[121] For many years, the U.S. Coast Guard used a section of Runway 12–30 for helicopter operations. The NYPD Aviation Unit uses this same segment.[195]: 39

A new Runway 6–24 was constructed in 1942. This 5,000-foot (1,500 m) x 300-foot (91 m) runway ran perpendicular to Flatbush Avenue, parallel to the old runway 6–24, but was located on the north side of the field.[249] At this time, the old runway 6–24 became taxiways T-1 and T-2.[143] Runways 1–19 and 12–30 were lengthened to 5,000-foot (1,500 m) x 300 feet (91 m).[249]

Around 1952, Runway 1–19 was expanded again to 7,000 feet (2,100 m), and Runway 12–30 was expanded to 5,500 feet (1,700 m). The new runway 6–24 was also lengthened to 6,000 feet (1,800 m).[163][164] In 1965, the Hangar Row apron was expanded and Runway 15–33 was modified to become the 4,500-foot (1,400 m) x 300-foot (91 m) taxiway T-10,[250]

There were three seaplane runways on the eastern coast. They were numbered 12–30, 18–36, and 7–25; the first two runways were built as part of the original seaplane base in 1933, while runway 7–25 was added later. There was also a turning basin at the intersection of runways 18–36 and 7–25.[65] The eastern coast also contains a 750-foot-long (230 m), 40-foot-wide (12 m) taxiway for the Coast Guard. It ends in a wooden seaplane ramp that was 260 feet (79 m) long by 50 feet (15 m) wide.[251]

Field

[edit]The Goldenrod and Tamarack Campgrounds are located near Hangar B.[10][224] It is the only legal campground in New York City.[229][252] However, the 46 campsites in the Floyd Bennett Field campground are classified as primitive: there are only portable toilets, and no electricity is provided.[252]

The General Management Plan of 1979 also called for the maintenance of grasslands around the field. The region's grasslands, the Hempstead Plains, had declined from its historic range due to urban sprawl.[231] As a result, the Grasslands Restoration And Management Project (GRAMP), a joint venture between the National Park Service and the Audubon Society, was created to maintain the grasslands in the middle of the field. The area managed by GRAMP consists of about 140 acres (57 ha) of land at the intersection of runways 6–24 (old), 1–19, and 12–30.[253] It is closed to the public.[202]: 3 [10] Runways 1-19 and 12-30 were also vegetated, and vehicular barriers were placed across some of the runways.[231]

The triangle-shaped Ecology Village is located at the south end of the field, between runways 30 and 33.[10][224] There are several hundred pine trees in the Ecology Village, which were first planted around 1974.[9] The Ecology Village, an environmental education program for students and specially trained teachers in cooperation with the New York City Department of Education, allows classes of students from the fourth to eighth grades to camp there for a night.[254] In the summer, the campgrounds are available on a permit basis for non-profit organizations and certified adult leaders.[255]

The North Forty Natural Area is located on the northern side of the airport, to the south of the Belt Parkway. It was formerly the Navy's munition storage area.[231] The natural area contains a hiking trail, a natural woodland area, and a sandy area with shrubs.[256][229] The 2-acre (0.81 ha) freshwater Return-A-Gift pond, built circa 1980, is also located in the North Forty Area, near the clear flight path zone for Runway 12–30.[231][256][229]

Coast

[edit]The former Coast Guard base is located along the eastern coast of Floyd Bennett Field.[95][97][99] As originally constructed, it contained a hangar, garage, radio station area, barracks, taxiway, apron, and runway.[251] The former Navy base is also located here. It includes Hangars A and B, barracks, two seaplane ramps, and maintenance buildings.[144]

The Navy developed a boat basin and recreation area along the coast during World War II.[144] After World War II, the Navy renovated the area, demolishing two baseball fields and replacing them with a running track.[155]

Current use

[edit]

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) has divisions located on the former airfield. The department's aviation base is housed in space leased from the National Park Service that was once CGAS Brooklyn,[189][257] and is also now headquarters for the New York City Police Department Emergency Service Unit.[258][257] The Driver Training Unit is also located there, using a section of former runway to teach officers to operate many different vehicles used by the department.[189][257]

The New York City Department of Sanitation Training Center is located in Tylunas Hall, the former Building 278. Part of the former runway is used for training drivers.[177][196]

The United States Park Police (USPP) operates out of the District 9 station, located in the former Building 275. It is responsible for police coverage of the New York areas of the Gateway National Recreation Area. The National Park Service's Jamaica Bay Unit Headquarters is located in Building 96.[259]

The Civil Air Patrol's Floyd Bennett Composite Squadron regularly meets at the former airfield.[260] The southern section of Floyd Bennett Field is also home to the 6th Communication Battalion of United States Marine Corps Reserve.[212]

Notable flights

[edit]Floyd Bennett Field hosted many famous aviators during the later years of the "Golden Age of Aviation" in the 1930s. This arose from a variety of optimal conditions, including the weather, geography, modern infrastructure, and low commercial usage.[63] As a result, Floyd Bennett Field was either the origin or destination for many record breaking flights, including 26 around-the-world or transoceanic flights and 10 transcontinental flights.[63][261][262]

On July 28–30, 1931, Russell Norton Boardman and John Louis Polando flew a Bellanca Special J-300 high-wing monoplane named Cape Cod to Istanbul in 49:20 hours, establishing a straight-line distance record of 5,011.8 miles (8,065.7 km).[263][264] As the runway at Floyd Bennett Field was only 5,000 feet (1,500 m) long, they needed to remove a fence and clear a parking lot to add another thousand feet to meet their required takeoff distance. The phone and electric utilities even took down poles along Flatbush Avenue.[265][266] Seventeen minutes after Boardman and Polando departed, Hugh Herndon Jr. and Clyde Pangborn flew a Red Bellanca CH-400 Skyrocket, named Miss Veedol, to Moylgrove, Wales, in 31:42 hours. They stopped in Japan on their flight around the world, flew directly to Wenatchee, Washington, on October 4, and landed at Floyd Bennett Field on October 17, 1931.[267][264]

At least thirteen notable transcontinental flights from 1931 to 1939 either began or ended at Floyd Bennett Field:

- On August 29, 1932, James G. Haizlip flew a Wedell-Williams Model 44, powered by a Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior engine, from Floyd Bennett Field to Los Angeles, California, in 10:19 hours, establishing a transcontinental record. The same day, Colonel Roscoe Turner also flew a Weddell-Williams, powered by a Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior engine, to Los Angeles, California, in 10:58:39 hours, having been beaten by Haizlip.[268][68]

- On November 14, 1932, Turner flew a Weddell-Williams to Burbank, California, in 12:33 hours, establishing a new East–West record.[262]

- On June 2, 1933, Lieutenant Commander Frank Hawks flew a Northrop Gamma, powered by a Wright Whirlwind engine, from Los Angeles, California, to Floyd Bennett Field in 13:26:15 hours, establishing a new West–East non-stop record.[269][262]