Charles Joseph Staniland

Charles Joseph Staniland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 June 1838 |

| Died | 16 June 1916 (aged 77) Birmingham, Warwickshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation(s) | Artist and illustrator |

| Years active | 1861[1]–1906 |

| Known for | Depiction of marine scenes |

| Notable work | The Emigrant Ship |

Charles Joseph Staniland ROI RI (19 June 1838[2] – 16 June 1916[3]: 464 ) was a prolific British genre, historical, and marine painter and a leading Social Realist illustrator.[4] He was a mainstay of the Illustrated London News and The Graphic in the 1870s and 1880s.[5]

Early life

[edit]Staniland was born at Kingston upon Hull in Yorkshire on (19 June 1838)[2] the son of Joseph Staniland, a merchant. He studied at the Birmingham School of Art under David Wilkie Raimbach,[note 1] at the Heatherley School of Fine Art, and the Normal Training School of Art in South Kensington.[4] He was admitted as a student of the Royal Academy on 2 May 1861, having successfully completed his probationary term.[7]

He married Elizabeth Parsons Buckman (c. 1844–1920) in Edgbaston, Warwick, on 15 September 1868.[8]. The couple had five children, all of whom survived to adulthood:

- Charles Norman Staniland (12 March 1871 – 31 May 1935)[9][10][note 2]

- Maud Elizabeth Staniland (born 6 February 1873)[11][note 3]

- Ellen Laura Sylvia Staniland (born 7 March 1874)[13][note 4]

- Catherine Wells Staniland (born 20 November 1877)[15][note 5]

- Eric Flemming Staniland (17 December 1880 – 23 June 1943)[20][21] [note 6]

By 1871 Staniland was living with his wife and first child at Hogarth Cottage in Chiswick, and was doing well enough to have a monthly nurse[note 7] as well as a servant. By 1881, he was living at 15 Steele's Road in Hampstead with his wife and all five of his children. He also had two live-in domestic servants and a governess for his children. The governess was Rosa Wells and her brother,[note 8] Josiah[note 9] Robert Wells (c. 1849–1897), an artist, was a boarder.

Staniland and Wells collaborated on several book illustration projects including The Three Admirals by William Henry Giles Kingston (Griffith & Farran. London 1878) and The Pirate Island by Harry Collingwood (Blackie and Son, London, 1885). Wells was the principal marine artist for The Illustrated London News for 1873–1883, specialising in marine subjects and ship portraits.[22] Houfe refers to him as the "Fleet Special Artist" of Illustrated London News.[24] Wells was still living with the Stanilands at the time of the 1891 census. Wells died on 27 June 1897 in Brookwood and Holloway Mental Hospital.[25][note 10]

Staniland was living with his wife and his three unmarried children at 3 Hawkswood Crescent, in Chingford, Essex, at the time of the 1901 census. By 1911, he was living with his daughter Catherine at 1 Millfield Villas, Fleet, Hampshire. His wife was with their daughter Ellen's husband and family at the time of the census. It is not clear if the couple had split up or if his wife was just on a visit.

Staniland died on 16 June 1916, at 134 Oxford Road, Acock's Green, Birmingham. He does not appear to have left a will. His wife survived until 1920.[3]: 464

Works

[edit]Staniland worked as a painter and as an illustrator. He produced a large volume of work for the illustrated newspapers.

Painting

[edit]Staniland began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1863 and continued to do so irregularly until 1881.[note 11]

Staniland was elected an associate of the RI in 1875, and became a full member in 1879. He resigned in 1890. He was a member of the ROI from his election in 1883 until his resignation in 1896.

Staniland painted in both watercolours and oils, and sometimes painted on a theme. In the case of The Emigrant Ship, Staniland exhibited a watercolour The last Day in Old England at the RI in 1875. This showed a party of emigrants about to leave the country, in a scene near the docks. The Globe said that the watercolour was "full of suggestion". In the Emigrant Ship also known as Good-Bye! we see the quayside as the ship is about to depart. The Liverpool Mercury stated that the painting was "full of heart-rending scenes in tearing asunder family ties" and that the painting was truly "a splendid work. . . The subject is well chosen as regards the position of the vessel, and there is a beautiful bit of dim smoky distance, so like London, and so cleverly done. To those who like this kind of subject it will prove a world of pleasure in examining for years.[29] Treuherz notes that among other social realist themes The Graphic publish several scenes of emigrants leaving by ship, with lively portrayals of both the excitement and pain of departure,[30]: 78 and cites this work by Staniland as an example.[30]: 136

-

The Lotus Eaters (watercolour and pencil heightened with white, 75x122 cm), 1883

-

An émeute (popular uprising) in the 16th century. (oil on canvas 102x128 cm), 1874

-

At the Back of Church (pencil and watercolour 51x92 cm), 1876

-

The Emigrant Ship (Oil on canvas 104x176 cm), 1878

Magazine and newspaper illustration

[edit]As an illustrator, Staniland was primarily a newspaper and magazine illustrator. Staniland became a staff member of the Illustrated London News and later of The Graphic.[4] He contributed to a wide range of magazines including:

- Atalanta[3]: 464

- Aunt Judy's Magazine[3]: 464

- The Boy's Own Paper[5]

- The British Workman[3]: 464

- Cassell's Family Magazine[5]

- The Children's Friend[5][3]: 464

- Chums[5]

- The English Illustrated Magazine[5]

- Golden Hours[3]: 464

- Good Words[3]: 464

- Harper's Weekly[3]: 464

- The Illustrated London News[5]

- The Leisure Hour[5]

- London Society[3]: 464

- Longman's Magazine[3]: 464

- The Pall Mall Magazine[5]

- The Quiver[5]

- Short Stories[3]: 464

- The Strand Magazine[3]: 464

- The Wide World Magazine[5]

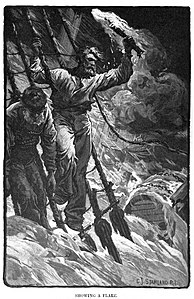

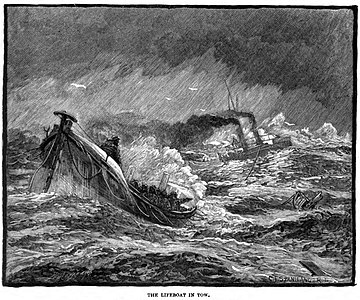

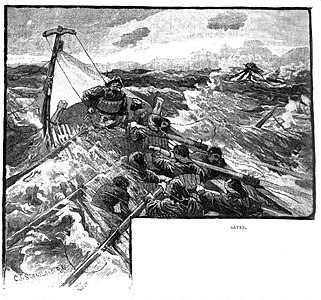

In 1886 Staniland not only illustrated but also authored a two part account of the Lifeboats and Lifeboat-men of Great Britain. This ran in The English Illustrated Magazine in February and March of that year.

-

The lifeboat Station

-

Testing self-righting boats

-

Showing a Flare

-

The Look Out

-

The Alarm Bell

-

The Rush for the Lifeboat

-

Waiting to Launch

-

The Launch

-

Lifeboat in Tow

-

Taking the crew off by jib-boom

-

Veering down to the Wreck

-

On the Sands

-

Saved

Book illustration

[edit]Kirkpatrick lists over 90 books illustrated by Staniland.[3]: 464-467 Some of these were illustrated in collaboration with Wells.

Among the authors that Staniland illustrated for were:[3]: 464-467

- Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), a prolific Danish author best remembered for his fairy tales.

- Christabel Rose Coleridge (1843–1921), who wrote improving stories for children.

- Harry Collingwood (1843–1922), a writer of boys' adventure fiction, usually in a nautical setting.

- George Manville Fenn (1831–1909), a prolific author of fiction for young adults.

- Thomas Frost (1821–1908), an English radical journalist and writer.

- G. A. Henty (1832–1902), a prolific writer of boy's adventure fiction, often set in a historical context, who had himself served in the military and been a war correspondent.

- F.M. Holmes

- Ascott R. Hope (1846–1927), a prolific author of children's books, especially school stories, and of Black's Guides.

- W. H. G. Kingston (1814–1880), who wrote boy's adventure fiction.

- Emma Leslie (1838–1909), Emma Boultwood, wrote more than 100 books, mostly juvenile and historical titles with a Christian message.[31]

- Frederick Marryat (1792–1848), a Royal Navy officer who wrote adventure books for children.

- Georgina Norway (1833–1915), who wrote adventure fiction for children as "G. Norway".

- Eliza F. Pollard (1839–1901), a polific author who turned to fiction in 1864 after a brief stint as a governess.[32]

- Charles Napier Robinson (1849–1938), a Royal Naval officer who on retirement, became a journalist on naval matters and published the journal Navy and army illustrated : a magazine descriptive and illustrative of everyday life in the defensive service of the British Empire..

- Walter Scott (1771–1832), the Scottish historical novelist, poet, and historian who wrote Ivanhoe.

- Edward Whymper (1840–1911), an English explorer, mountaineer, illustrator, and author. Brother to Frederick Whymper.

- Charlotte Mary Yonge (1823–1901), who became a Sunday School teacher aged seven and remained one for the next seventy one years, she wrote to promote her religious views.[33]

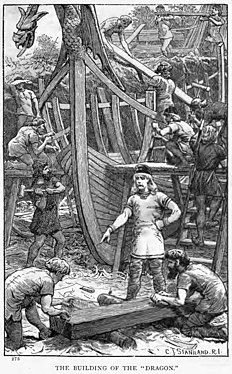

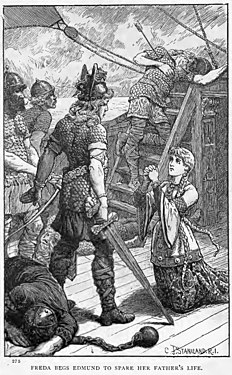

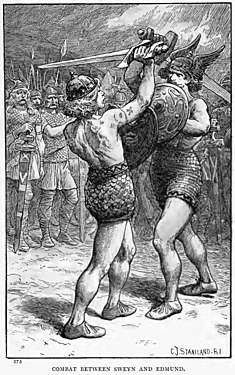

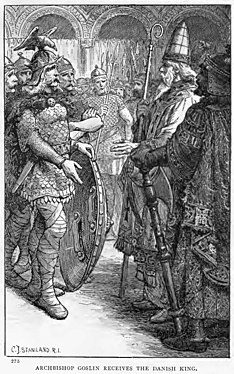

In 1886 Staniland illustrated The Dragon and The Raven, or The Days Of King Alfred. by George Alfred Henty (Blackie & Son, London 1886)[34]. The illustrations were made with line blocks from fine pen-drawings drawn in a manner that makes the picture look like wood-engravings.[35]

-

Confronting the Danes

-

Cooking in the Hut

-

Building the Dragon

-

Freda Pleads for her Father's Life

-

Combat between the Hero and Villain

-

The Archbishop receives the king

-

I am near you

-

Freda Restored

Assessment

[edit]Houfe states that "Staniland’s strength was in marine illustrations where the ships and tackle were seen at close quarters and the working seaman was observed in large scale" and that "His many contributions to The Illustrated London News and The Graphic were a mainstay of those periodicals in the 1870s and 1880s, readers had practically to wipe the brine from their faces as they turned the pages."[5] The Hampstead and Highgate Express called him a "dextrous and humourous" artist.[36]

Houfe also stated that Staniland "was also an excellent portrait artist and painted still-life and bird subjects in watercolour."[5] His social realist images for the Graphic, particularly those of mining, were much admired by Van Gogh.[4]

The best auction results for Staniland reported by Benezit are:

- London, 21 July 1887, The Lotus Eaters (1883, watercolour and pencil heightened with white, 75x122 cm) 4,800 GBP.

- London, 5 March 1993, At the Back of the Church (1876, pencil and watercolour, 151.1x91.6 cm) 8,050 GBP.

- London, 6 Nov 1996, The Dutch Delegation Offering the Crown of Holland to Henri III of France (1884, oil on canvas, 106.5x184 cm) 10,120 GBP. The same piece had sold for 5,500 GBP in London 13 years earlier on 19 Oct 1983.[37][note 12][note 14]

Notes

[edit]- ^ D. W. Raimbach was the son of engraver Abraham Raimbach. He was appointed headmaster of the Birmingham School of Art in 1858.[6]

- ^ Occupation listed as Electrical Engineer in the 1911 census, by which time he was living with his wife and four children.

- ^ Her occupation was an insurance clerk in the 1901 census. She married Percy Ross Boyle (born 6 March 1871) a clerk, at Tooting on 2 June 1906.[12]

- ^ She married Charles Pervical Cousins on 4 June 1898.[14]

- ^ Catherine Wells seems to have had an issue with her age, as she recorded it as 30 years of age in the 1911 census, when she was 33. She merely gave her age as "Full" at her marriage in Fleet to bank clerk Norman Brain Edwards (26 November 1887 – 26 February 1952)[16][17][18] nearly ten years younger, and gave her year of birth as 1885 in the 1939 Register, though with the correct day and month.[16] However her baptismal record of 25 October 1878 gives her date of birth as 20 November,[15] presumably in 1877, her birth was registered in the first quarter of 1878,[19], and the 1881 census gives her age as three.

- ^ He gives his year of birth as 1878 in the 1939 Register[20], but his baptismal record and the 1881 census give his year of birth as 1880. His occupation was that of farmer in the 1901 census. but he was the manager of a bottling plant by 1939.

- ^ His son was only three weeks old at the time of the census.

- ^ Kirkpatrick refers to Josiah as Rosa's husband, but the census return for 1881 shows both Rosa and Josiah as unmarried, earlier census returns show that Josiah had a sister Rosa of the correct age, and the Suffolk Artists website identify them as brother and sister.[22]

- ^ Johnson and Greutzner identify him as Joseph Robert Wells.[23]

- ^ He had been committed by his sister Rosa on 30 October 1896, and was diagnosed with General Paralysis.[25]

- ^ Staniland exhibited as follows from 1880: five works at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, one work at the Fine Art Society, one work at the Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts, 13 works at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, nine works at the Manchester City Art Gallery, one work at the Royal Academy (in 1881), and 26 works at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours.[26] This list excludes his exhibits before 1881. He had started exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1863 and exhibited there in 1865, 1874, 1877, and 1878.[27] As well as the five exhibits at the Royal Academy he also exhibited twice at the British Institution and seven times at the Society of British Artists between 1861 and 1878.[28] Wood notes that he exhibited 62 works, including at the New Watercolour Society.[1]

- ^ Staniland had registered his copyright of this work on 26 April 1882, presumably with a view to the production of prints.[38]

- ^ The incident is described on page 96 of Volume I of Motley's book. However, Motley states that, unlike the painting, where the Dutch Envoys were received in open court, they were in fact received in the King's cabinet, where he was accompanied only by the Duke of Joyeuse, the Count of Bouscaige, M. de Valette, and the Count of Château Vieux. Motley describes the basket of puppies. Henry declined the offer of the crown, and the envoys left disheartened after three months of negotiations.[39]

- ^ In its review of The Dutch Envoy offer the Crown of the Netherlands to Henri III of France the Liverpool Mercury states that the scene is based on an incident related in John Lothrop Motley's The United Netherlands[note 13] The Mercury describes the picture thus: "The composition consists of twenty-seven figures, the central group consisting of the blasé and frivolous King and his courtiers. The former is amusing himself with a litter of puppies which are in a basket and slung round his neck. . . The contrast between the frivolous and effeminate King and his court, compared with the stern countenances of the Dutch envoys, one of whom is reading an address, constitute the point of the picture." The Mercury was full of praise for the painting: "There are some good grouping and clever figure-painting in this picture, and the accessories particularly are worked out and painted with great care."[40]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Woods, Christopher (1978). The Dictionary of Victorian Painters (2nd ed.). Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-902028-72-2. Retrieved 5 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Greenwall, Ryno (1992). Artists and Illustrators of the Anglo-Boer War. Vlaeberg, Western Cape, South Africa: Fernwood Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-9583154-2-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kirkpatrick, Robert J. (2019). The Men Who Drew For Boys (And Girls): 101 Forgotten Illustrators of Children's Books: 1844-1970. London: Robert J. Kirkpatrick.

- ^ a b c d "Charles Joseph Staniland RI ROI {1838-1016)". Chris Beetles Gallery. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Houfe, Simon (1996). Dictionary of 19th Century British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 310. ISBN 1-85149-193-7.

- ^ Strickland, Walter George (1913). A Dictionary of Irish Artists. Vol. II: L to Z. Dublin: Maunsel & Company. pp. 271–272. Retrieved 30 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Local Intelligence". Hull Packet (Friday 10 May 1861): 5. 10 May 1861. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Library of Birmingham (2013). "Year Range: 1867-1868: Reference Number: DRO 53; Archive Roll: M148: 1868 Marriage solemnized at the Parish Church in the Parish of Edgbarton in the County of Warwick: 15 September: Charles Joseph Staniland". Birmingham, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1937. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives (2010). "Year: 1844-1893, Reference Number: dro/079/001: Baptisms Solemnized in the Parish of Turnham Green in the County of Middlesex in the year 1871: 11 April: Charles Norman Staniland". London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Staniland and the year of death 1935". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ National Archives (29 September 1939). 1939 Register: Reference: RG 101/1195D: E.D. CGEO. Kew: National Archives.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives (2013). "Year Range: 1903-1920: Reference Number: p95/nic/022: 1906 Marriage solemnized at The Parish Church in the Parish of Tooting in the Parish of London: 2 June: Percy Ross Boyle". London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- ^ National Archives (29 September 1939). 1939 Register: Reference: RG 101/1499F: E.D. DBRT. Kew: National Archives.

- ^ "Marriages". Irish Independent (Wednesday 08 June 1898): 1. 8 June 1898. Retrieved 1 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b London Metropolitan Archives (2010). "Year: 1844-1893, Reference Number: dro/079/001: Baptisms Solemnized in the Parish of Turnham Green in the County of Middlesex in the year 1878: 25 Oct: Catherine Wells Staniland". London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b National Archives (29 September 1939). 1939 Register: Reference: RG 101/4490C: E.D. NJWV. Kew: National Archives.

- ^ "Norman Brain Edwards". Find a Grave. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Edwards and the year of death 1955". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ a b National Archives (29 September 1939). 1939 Register: Reference: RG 101/5702E: E.D. QEJQ. Kew: National Archives.

- ^ "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Staniland and the year of death 1943". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Wells, Josiah Robert". Suffolk Artists. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Johnson, J.; Greutzner, A. (1986). The Dictionary of British Artists 1880-1940. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 537.

- ^ Houfe, Simon (1981). Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914 (Rev. ed.). Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 146. ISBN 9780902028739. Retrieved 14 July 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "Year Range: 1896-1899: Reference Number: 3237/5/3. Admission No. 1679, 31 October 1896". Surrey, England, Admissions to Brookwood and Holloway Mental Hospitals, 1867-1900. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com. 2015.

- ^ Johnson, J.; Greutzner, A. (1986). The Dictionary of British Artists 1880-1940. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 477.

- ^ Graves, Algernon (1906). The Royal Academy of Arts: A completed Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol. 7: Sacco to Tofano. London: Henry Graves and Co. Ltd., and George Bell and Sons. pp. 234–235. Retrieved 25 August 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Graves, Algernon (1884). A Dictionary of Artists who have exhibited works in the principle London exhibitions of oil paintings from 1760 to 1880. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 222. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081864062. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via The Hathi Trust (access may be limited outside the United States).

- ^ "Corporation Exhibition, Art Gallery. No VI". Liverpool Mercury (Tuesday 08 October 1878): 6. 8 October 1878. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Treuherz, Julian (1987). "Frank Holl: The Graver, greyer aspect of life". In Treuherz, Julian (ed.). Hard Times: Social Realism in Victorian art. London: Lund Humphries. Retrieved 1 October 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Author: Emma Leslie (1838–1909) (real name Emma Boultwood)". At the Circulating Library: A database of Victorian Fiction 1837-1901. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "Author: Eliza Fanny Pollard (1839–1911)". At the Circulating Library: A database of Victorian Fiction 1837-1901. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1989). "Yonge, Charlotte Mary (1823-1901)". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 685.

- ^ Henty, George Alfred (1886). he Dragon and The Raven, or The Days Of King Alfred. London: Blackie & Son. Retrieved 28 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Newbolt, Peter (1996). G.A. Henty, 1832-1902 : a bibliographical study of his British editions, with short accounts of his publishers, illustrators and designers, and notes on production methods used for his books. Brookfield, Vt.: Scholar Press. p. 639. ISBN 1-85928-208-3. Retrieved 4 August 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ "Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours". Hampstead & Highgate Express (Saturday 15 March 1890): 5. 15 March 1890. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Bénézit, Emmanuel (2006). Benezit Dictionary Of Artists. Vol. 13: Sommer-Valverane. Paris: Editions Gründ. p. 215. ISBN 978-2-7000-3083-9. Retrieved 11 September 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Copyright Office, Stationers' Company (26 April 1882). Oil painting of Dutch envoys offering the Crown of Holland to Henri III of France Who . . . Retrieved 27 September 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Motley, John Lothrop (1860). History of the United Netherlands, from the death of William the Silent, to the Synod of Dort. With a full view of the English-Dutch struggle against Spain, and of the origin and destruction of the Spanish Armada. Vol. I: 1584 1586. London: John Murray. pp. 94–95. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via The British Library.

- ^ "The Corporation Autumn Exhibition: Room 2, Oil Paintings". Liverpool Mercury (Monday 11 September 1882): 6. 11 September 1882. Retrieved 29 September 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

External links

[edit] Media related to Charles Joseph Staniland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Joseph Staniland at Wikimedia Commons Works related to Charles Joseph Staniland at Wikisource

Works related to Charles Joseph Staniland at Wikisource

- 1838 births

- 1916 deaths

- 19th-century British painters

- English watercolourists

- British portrait painters

- Alumni of the Royal Academy Schools

- British male painters

- English illustrators

- British illustrators

- British children's book illustrators

- Magazine illustrators

- Members of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters

- Members of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours

- Alumni of the Heatherley School of Fine Art

- 19th-century British male artists

- Artists' Rifles soldiers