Buddle pit

A buddle pit or buddle pond is an ore processing technique that separates heavier minerals from lighter minerals when the crushed ore is washed in water.[1] This technique was used in the mining industry to extract metals such as tin, lead and zinc. Many buddles seen today date from the Victorian era and are often circularly shaped. There was also a variation called the concave buddle, which had a concave bottom.[2]

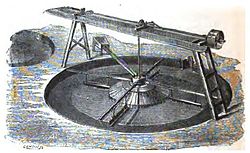

The pit, often constructed from stone, cement, or brick and mortar, contained water and used a set of brushes often powered by a water wheel which rotated in the water in order to agitate the mixture. The result of which was that the heavier and denser material - i.e. the ore - tended to collect at the centre of the pit, from where it could be retrieved. The byproduct was then drained off and disposed of.[3]

Usually a set of buddle pits were used to further refine the ore, where the processed ore was put in another buddle until the achieved concentration of the desired mineral was met.[4]

The following detailed extract comes from Machinery for Metalliferous Mines: A practical treatise for mining engineers, metallurgists and managers of mines, by E. Henry Davies, C. Lockwood and son, 1902 :

The concentrating machine for slimes, which has hitherto been a great favourite, is the round buddle, and this was perhaps due to the great simplicity of its construction, which permitted its being made out of the odds and ends of machinery usually to be found on a mine. The fixed and revolving cast-iron heads, shafting, bevel wheels, and driving pulleys, are usually procured from a firm of machinery makers.

The buddle itself consists of a shallow circular pit formed in the ground from 14 ft. to 22 ft. diameter, and from 1 ft. to 1½ ft. deep. The poorer the slimes the greater the diameter, and as the product from the buddle always requires re-treatment, it is usual to concentrate first in a machine of small diameter, and then to re-treat the concentrates thus produced in one of a larger diameter. The sides of the buddle pit are formed of stone or brick, set in mortar, and the floor, which has an inclination outwards of 1 in 30, is made either of smooth planed boards or cement run upon a layer of concrete. The centre head is from 6 ft. to 10 ft. in diameter, and may even be less. A revolving head is fixed to the shaft, and this carries four arms. The revolving head receives the slime waters from the trough, and distributes them on an even layer over the fixed head ; the liquid stream, which should be in a uniform thin film, falls over the edge of the fixed head, and distributes itself outwards over the sloping floor of the buddle towards the circumference, depositing in its passage the rich ore it contains, according to its specific gravity, the richest first, close to the fixed head, and the poorest at the circumference. To each of the four arms a board is attached, carrying a cloth or a series of brushes, which sweep round and smooth out each successive layer of mineral as soon as it is formed. In some cases sprays of fresh water are used instead of the cloths or brushes, the number of revolutions in either case being 3 or 4 per minute.

The outflow of the waste waters takes place through the small sluice gate shown in the circumference of the huddle. In the door of this sluice is a vertical line of holes, and, as the layer of mineral thickens on the floor, a plug is placed in the lowest hole, and so successively up the series, until the full thickness of the deposit equal to the height of the cone is reached. At this point the machine is stopped, a groove is cut from the cone to the circumference, and samples of the ore are taken and washed on a vanning shovel. By this means an idea is formed as to where the divisions should be made ; for at the head the concentrates are rich in galena, and then follow the mixed ores, either of galena, blende, and gangue, if blende is present, or of galena and gangue, if it is absent. Two qualities of the mixed ores are formed. Rings are formed around the deposit on the buddle to indicate the division lines. The rich heads are taken out and reworked once in another buddle, when they will be rich enough to be sent to the dolly tub. The middles are likewise re-treated, the ores of approximately the same percentage being treated in the same machine until all the mineral is abstracted, and the waste contains not more than ½ per cent. of lead, and 1 to 1½ per cent. of zinc. By successive re-treatment the minerals may thus be enriched up to 50 to 60 per cent. Pb., and when blende is present, to about 42 per cent. Zn. These concentrates may either be sold as they are, or further enriched in a dolly tub.

The great drawbacks to the round buddle are the facts that no clean products can be made straight away. The mineral must be handled several times, always a costly proceeding, and the machine must be stopped when full, and lie idle until emptied. A large number of buddles are always required to cope with the slimes from even a small mill, while in large mills, especially when blende is present, from sixteen to twenty would be needed.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sine Project - Term Definitions: BUDDLE

- ^ Machinery for Metalliferous Mines: A practical treatise for mining engineers, metallurgists and managers of mines, by E. Henry Davies, C. Lockwood and son, 1902

- ^ Undiscovered Wales: Fifteen Circular Walks, by Kevin Walker, Francis Lincoln, 2010

- ^ Mining and mining machinery: explaining the methods of obtaining minerals, precious stones, &c., in all parts of the world, by Sydney Ferris Walker, 1913