Indian eagle-owl

| Indian eagle-owl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Bubo |

| Species: | B. bengalensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bubo bengalensis | |

| |

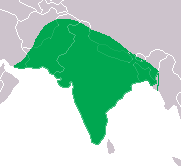

| Bounding distribution of Indian eagle-owl | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Urrua bengalensis[3] | |

The Bengal eagle-owl (Bubo bengalensis), also widely known as the Indian eagle-owl or rock eagle-owl, is a large horned owl species native to hilly and rocky scrub forests in the Indian Subcontinent. It is splashed with brown and grey, and has a white throat patch with black small stripes. It was earlier treated as a subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl. It is usually seen in pairs. It has a deep resonant booming call that may be heard at dawn and dusk.

Taxonomy

[edit]Bubo bengalensis was the scientific name used by James Franklin in 1831 for an eagle-owl, that was collected in the Bengal region of the Indian Subcontinent.[2]

Description

[edit]

This species is often considered a subspecies of the Eurasian eagle-owl Bubo bubo and is very similar in appearance. The facial disk is unmarked and has a black border, a feature that is much weaker in the Eurasian form. The base of the primaries is unbanded and rufous. The tail bands have the tawny bands wider than the black ones. A large pale scapular patch is visible on the folded wing.[4] The inner claws are the longest. The last joint of the toes are unfeathered.[5]

The taxonomy of the group is complex due to a large amount of variation.[6] Dementiev was the first to consider the possibility of B. bengalensis being distinct within the Bubo bubo group. However, Charles Vaurie noted that this species as well as B. ascalaphus appeared to be distinct and not part of a clinal variation. There is a lot of colour variation with the ground colour being dark brown above while some are pale and yellowish. On dark birds the streaks coalesce on the hind crown and nape but are narrow in pale birds. However, Vaurie notes that despite the variation, they are distinct from neighbouring forms B. b. tibetanus, B. b. hemachalana and B. b. nikolskii, in being smaller and richly coloured.[7][8] Stuart Baker noted that there were two plumage variants that were seen across their range, one plumage has the back and scapulars spotted in white while the other form has a reduced number of white spots on the feathers of the back and the dark streaking on the back, neck and scapulars being prominent.[9]

Chicks are born with white fluff which is gradually replaced by speckled feathers during the pre-juvenile moult after about two weeks. After a month or so they go through a basic moult and a brownish juvenile plumage is assumed with the upperparts somewhat similar to adults but the underside is downy. The full adult plumage is assumed much later.[10]

Distribution

[edit]

They are seen in scrub and light to medium forests but are especially seen near rocky places within the mainland of the Indian Subcontinent south of the Himalayas and below 1,500 m (4,900 ft) elevation. Humid evergreen forest and extremely arid areas are avoided. Bush-covered rocky hillocks and ravines, and steep banks of rivers and streams are favourite haunts. It spends the day under the shelter of a bush or rocky projection, or in a large mango or similar thickly foliaged tree near villages.

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]The deep resonant two-note calls are characteristic and males deliver these "long calls" mainly at dusk during the breeding season. The peak calling intensity is noticed in February.[11] Young birds produce clicks, hisses and open up their wings to appear larger than they are.[12][13] Nesting adults will fly in zig-zag patterns and mob any potential predators (including humans) who approach the nest.[14]

Its diet through much of the year consists of rodents, but birds seem to be mainly taken towards winter. Prey species of birds include francolins, doves,[15] Indian roller,[16] shikra, black kite, house crow and the spotted owlet. Birds the size of a peafowl are sometimes attacked.[17] Rodents noted in a study in Pondicherry were Tatera indica, Golunda ellioti, Rattus sp., Mus booduga and Bandicota bengalensis. Flying fox were also preyed on.[18] In Pakistan, Nesokia indica is an important prey item in their diet.[19] Mammals the size of an Indian hare (Lepus nigricollis) may be taken.[20] In Pakistan, it has preyed on Lepus capensis and Eupetaurus cinereus.[21]

When feeding on rodents, it tears up the prey rather than swallowing it whole.[22] Captives feed on about 61g of prey per day.[23]

The nesting season is November to April. The eggs number three or four and are creamy white, broad roundish ovals with a smooth texture. They are laid on bare soil in a natural recess in an earth bank, on the ledge of a cliff, or under the shelter of a bush on level ground.[15][16] The nest site is reused each year.[24] The eggs hatch after about 33 days and the chicks are dependent on their parents for nearly six months.[25]

In culture

[edit]This large owl with the distinctive face, large forward-facing eyes, horns and deep resonant call is associated with a number of superstitions. Like many other large owls, these are considered birds of ill omen. Their deep haunting calls if delivered from atop a house are considered to forebode the death of an occupant. A number of rituals involving the capture and killing of these birds have been recorded. Salim Ali notes a wide range of superstitions related to them but notes two as being particularly widespread. One is that if the bird is starved for a few days and beaten, it would speak like a human, predicting the future of the tormentor or bringing them wealth while the other involves the killing of the bird to find a lucky bone that moved against the current like a snake when dropped into a stream.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Bubo bengalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22688934A93211525. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22688934A93211525.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Franklin, J. (1831). "Catalogue of Birds, collected on the Ganges between Calcutta and Benares, and in the Vindhya Hills between the latter place and Gurrah Mundela on the Nerbudda, with characters of the New Species". Proceedings of the Committee of Science and Correspondence of the Zoological Society of London. 1 (10): 115–125.

- ^ Jerdon, T.C. (1839). "Catalogue of the birds of the peninsula of India, arranged according to the modern system of classification; with brief notes on their habits and geographical distribution, and description of new, doubtful and imperfectly described specimens". Madras Journal of Literature and Science. 10: 60–91.

- ^ Rasmussen, P.C. & Anderton, J.C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Vol. 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Ediciones. pp. 239–240.

- ^ Blanford, W.T. (1895). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. Birds. Volume 3. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 285–286.

- ^ Bowdler Sharpe, R. (1875). "Bubo bengalensis". Catalogue of the birds in the British Museum. Vol. 2. London: British Museum. pp. 25–27.

- ^ Whistler, H. & Kinnear, N.B. (1935). "The Vernay scientific survey of the eastern ghats (ornithological section), Part 12". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 38: 232–240.

- ^ Vaurie, C. (1960). "Systematic notes on Palearctic birds. No. 41, Strigidae, the genus Bubo". American Museum Novitates (2000). hdl:2246/5372.

- ^ Baker, E.C.S. (1927). "Bubo bubo turkomanus". The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. Birds. Volume 4 (Second ed.). London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 414–415.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. & Murugavel, T. (2009). "A preliminary report on the development of young Indian Eagle Owl Bubo bengalensis (Franklin, 1831) in and around Pondicherry,Tamilnadu and southern India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 1 (10): 519–524. doi:10.11609/jott.o1762.519-24.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2003). "On the "long call" of the Indian Great Horned or Eagle-Owl Bubo bengalensis (Franklin)" (PDF). Zoos' Print Journal. 18 (7): 1131–1134. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.18.7.1131-4.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2003). "Interspecific intimidatory behaviour in nestling Indian Eagle Owls Bubo bengalensis (Franklin)". Zoos' Print Journal. 18 (10): 1213–1216. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.18.10.1213-6.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2007). "A catalogue of auditory and visual communicatory traits in the Indian Eagle Owl Bubo bengalensis (Franklin, 1831)". Zoos' Print Journal. 22 (8): 2771–2776. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.1572.2771-6.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2004). "Inter-specific intimidatory behaviour of adult Indian Eagle Owls Bubo bengalensis (Franklin) in defence of their nestlings" (PDF). Zoos' Print Journal. 19 (2): 1343–1345. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.19.2.1343-5.

- ^ a b Dharmakumarsinhji, K.S. (1939). "The Indian Great Horned Owl [Bubo bubo bengalensis (Frankl.)]". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 41 (1): 174–177.

- ^ a b Eates, K.R. (1937). "The distribution and nidification of the Rock Horned Owl Bubo bubo bengalensis (Frankl.) in Sind". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 39 (3): 631–633.

- ^ Tehsin, R. & Tehsin, F. (1990). "Indian Great Horned Owl Bubo bubo (Linn.) and Peafowl Pavo cristatus Linn". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 87 (2): 300.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2001). "A preliminary report of the prey of the Eurasian Eagle-Owl (Bubo bubo) in and around Pondicherry". Zoos' Print Journal. 16 (5): 487–488. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.16.5.487-8.

- ^ Fulk, G.W. & Khokhar, A.R. (1976). "Short-tailed Mole Rat (N. indica) prey of great-horned owl (B. bubo)". Pakistan Journal of Zoology. 8: 97.

- ^ Kumar, S. (1995). "Possible predation of Blacknaped Hare by Great Horned Owl Bubo bubo in the Great Indian Bustard Sanctuary, Nanaj (Solapur), Maharashtra". Newsletter for Birdwatchers. 35 (1): 16–17.

- ^ Zahler, P. & Dietemann, C. (1999). "A note on the food habits of Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo bubo in northern Pakistan" (PDF). Forktail. 15: 98–99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2004). "Methods of analysing rodent prey of the Indian Eagle Owl Bubo bengalensis (Franklin) in and around Pondicherry, India". Zoos' Print Journal. 19 (6): 1492–1494. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.1117a.1492-4.

- ^ Ramanujam, M.E. (2000). "Food consumption and pellet regurgitation rates in a captive Indian Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo bengalensis)". Zoos' Print Journal. 15 (7): 289–291. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.15.7.289-91.

- ^ Osmaston, B.B. (1926). "The Rock Horned Owl in Kashmir". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 31 (2): 523–524.

- ^ Pande, S.; Pawashe, A.; Mahajan, M.; Mahabal, A.; Joglekar, C. & Yosef, R. (2011). "Breeding Biology, Nesting Habitat, and Diet of the Rock Eagle-Owl (Bubo bengalensis)". Journal of Raptor Research. 45 (3): 211–219. doi:10.3356/JRR-10-53.1. S2CID 84194153.

- ^ Ali, S. & Ripley, S.D. (1981). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 3 (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 273–275.

Other sources

[edit]- Perumal TNA (1985). "The Indian Great Horned Owl". Sanctuary Asia. 5 (3): 214–225.