Science Museum, London

The Science Museum | |

| Established |

|

|---|---|

| Location |

|

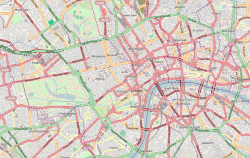

| Coordinates | 51°29′51″N 0°10′29″W / 51.49750°N 0.17472°W |

| Visitors | 2,956,886 (2023)[1] |

| Director | Ian Blatchford |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

| Science Museum Group | |

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.[2]

Like other publicly funded national museums in the United Kingdom, the Science Museum does not charge visitors for admission, although visitors are requested to make a donation if they are able. Temporary exhibitions may incur an admission fee.

It is one of the five museums in the Science Museum Group.

Founding and history

[edit]

The museum was founded in 1857 under Bennet Woodcroft from the collection of the Royal Society of Arts and surplus items from the Great Exhibition as part of the South Kensington Museum, together with what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum. It included a collection of machinery which became the Museum of Patents in 1858, and the Patent Office Museum in 1863. This collection contained many of the most famous exhibits of what is now the Science Museum.

In 1883, the contents of the Patent Office Museum were transferred to the South Kensington Museum. In 1885, the Science Collections were renamed the Science Museum and in 1893 a separate director was appointed.[3] The Art Collections were renamed the Art Museum, which eventually became the Victoria and Albert Museum.

When Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone for the new building for the Art Museum, she stipulated that the museum be renamed after herself and her late husband. This was initially applied to the whole museum, but when that new building finally opened ten years later, the title was confined to the Art Collections and the Science Collections had to be divorced from it.[4] On 26 June 1909 the Science Museum, as an independent entity, came into existence.[4]

The Science Museum's present quarters, designed by Sir Richard Allison, were opened to the public in stages over the period 1919–28.[5] This building was known as the East Block, construction of which began in 1913 and was temporarily halted by World War I. As the name suggests it was intended to be the first building of a much larger project, which was never realized.[6] However, the museum buildings were expanded over the following years; a pioneering Children's Gallery with interactive exhibits opened in 1931,[4] the Centre Block was completed in 1961–3, the infill of the East Block and the construction of the Lower & Upper Wellcome Galleries in 1980, and the construction of the Wellcome Wing in 2000 result in the museum now extending to Queen's Gate.

Centennial volume: Science for the Nation

[edit]The leading academic publisher, Palgrave Macmillan, published the official centenary history of the Science Museum on 14 April 2010. The first complete history of the Science Museum since 1957, Science for the Nation: Perspectives on the History of the Science Museum is a series of individual views by Science Museum staff and external academic historians of different aspects of the Science Museum's history. While it is not a chronological history in the conventional sense, the first five chapters cover the history of the museum from the Brompton Boilers in the 1860s to the opening of the Wellcome Wing in 2000. The remaining eight chapters cover a variety of themes concerning the museum's development.

Galleries

[edit]The Science Museum consists of two buildings – the main building and the Wellcome Wing. Visitors enter the main building from Exhibition Road, while the Wellcome Wing is accessed by walking through the Energy Hall, Exploring Space and then the Making the Modern World galleries (see below) at ground floor level.

Main building – Level 0

[edit]The Energy Hall

[edit]

The Energy Hall is the first area that most visitors see as they enter the building. On the ground floor, the gallery contains a variety of steam engines, including the oldest surviving James Watt beam engine, which together tell the story of the British Industrial Revolution.

Also on display is a recreation of James Watt's garret workshop from his home, Heathfield Hall, using over 8,300 objects removed from the room, which was sealed after his 1819 death, when the hall was demolished in 1927.[7]

Exploring Space

[edit]Exploring Space is a historical gallery, filled with rockets and exhibits that tell the story of human space exploration and the benefits that space exploration has brought us (particularly in the world of telecommunications).

Making the Modern World

[edit]

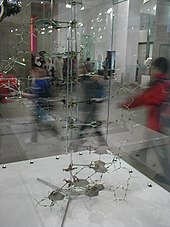

Making the Modern World displays some of the museum's most remarkable objects, including Puffing Billy (the oldest surviving steam locomotive), Crick's double helix, and the command module from the Apollo 10 mission, which are displayed along a timeline chronicling man's technological achievements.

A V-2 rocket, designed by German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, is displayed in this gallery. Doug Millard, space historian and curator of space technology at the museum, states: "We got to the Moon using V-2 technology but this was technology that was developed with massive resources, including some particularly grim ones. The V-2 programme was hugely expensive in terms of lives, with the Nazis using slave labour to manufacture these rockets".[9][10]

Stephenson's Rocket used to be displayed in this gallery. After a short UK tour, since 2019 Rocket is on permanent display at the National Railway Museum in York, in the Art Gallery.

Main Building – Level 1

[edit]Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries

[edit]The Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries is a five-gallery medical exhibition which spans ancient history to modern times with over 3000 exhibits and specially commissioned artworks.[11] Many of the objects on display come from the Wellcome Collection started by Henry Wellcome.[12] One of the commissioned artworks is a large bronze sculpture of Rick Genest titled Self-Conscious Gene by Marc Quinn.[13] The galleries occupy the museum's entire first floor and opened on 16 November 2019.[11]

Main Building – Level 2

[edit]The Clockmakers Museum

[edit]The Clockmakers Museum is the world's oldest clock and watch museum which was originally assembled by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in London's Guildhall.

Science City 1550–1800: The Linbury Gallery

[edit]The Science City 1550–1800: The Linbury Gallery shows how London grew to be a global hub for trade, commerce and scientific enquiry.

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery

[edit]The Mathematics: The Winton Gallery examines the role that mathematicians have had in building our modern world. In the landing area to access the gallery (stair C) is a working example of Charles Babbage's Difference engine No.2. This was built by the Science Museum and its main part completed in 1991, to celebrate 200 years since Babbage's birth, and was designed by Zaha Hadid Architects.[14][15]

Information Age

[edit]

The Information Age gallery has exhibits covering the development of communications and computing over the last two centuries. It explores the six networks that have transformed global communications: The Cable, The Telephone Exchange, Broadcast, The Constellation, The Cell and The Web[16] It was opened on 24 October 2014 by the Queen, Elizabeth II, who sent her first tweet from here.[17]

Main Building – Level 3

[edit]Wonderlab: The Equinor Gallery

[edit]One of the most popular[citation needed] galleries in the museum is the interactive Wonderlab:The Equinor Gallery, formerly called Launchpad. The gallery is staffed by Explainers who demonstrate how exhibits work, conduct live experiments and perform shows to schools and the visiting public.

Flight

[edit]The Flight gallery charts the development of flight in the 20th century. Contained in the gallery are several full sized aeroplanes and helicopters, including Alcock and Brown's transatlantic Vickers Vimy (1919), Spitfire and Hurricane fighters, as well as numerous aero-engines and a cross-section of a Boeing 747. It opened in 1963 and was refurbished in the 1990s.[18]

Wellcome Wing

[edit]Power Up (Level 1)

[edit]Power Up is an interactive gaming gallery showcasing the history of video games and consoles from the past 50 years. Visitors can play on over 150 consoles, featuring consoles from the Binatone TV Master to the Play Station 5.

Tomorrow's World (Level 0)

[edit]The Tomorrow's World gallery hosts topical science stories and free exhibitions including:

- Mission to Mercury: Bepi Columbo[19]

- Driverless: Who's in control? (exhibition ended January 2021)[20]

IMAX: The Ronson Theatre (Entrance from Level 0)

[edit]The IMAX: The Ronson Theatre is an IMAX cinema which shows educational films (most in 3-D), as well as blockbusters and live events.[21] It features a screen measuring 24.3 by 16.8 metres, with both a dual IMAX with Laser projection system and a traditional IMAX 15/70mm film projector, and an IMAX 12-channel sound system.[22]

Who Am I? (Level 1)

[edit]Visitors to the Who Am I? gallery can explore the science of who they are through intriguing objects, provocative artworks and hands-on exhibits.

Energy Revolution: The Adani Green Energy Gallery (Level 2)

[edit]Energy Revolution: The Adani Green Energy Gallery explores how the world can generate and use energy more sustainably to urgently reduce carbon dioxide emissions from global energy systems and limit the impact of climate change.

Temporary and touring exhibitions

[edit]The museum has some dedicated spaces for temporary exhibitions (both free and paid-for) and displays, on Level -1 (Basement Gallery), Level 0 (inside the Exploring Space Gallery and Tomorrow's World), Level 1 (Special Exhibition Gallery 1) and Level 2 (Special Exhibition Gallery 2 and The Studio). Most of these travel to other Science Museum Group sites, as well as nationally and internationally.

Past exhibitions have included:

- Codebreaker, on the life of Alan Turing (2012–2013).[23]

- Unlocking Lovelock, which explored the archive of James Lovelock (ended 2015).[24]

- Cosmonauts: Birth of Space Age (ended 2016).[25]

- Wounded – Conflict, Casualties and Care (2016–2018)[26] – timed to commemorated the centenary of the Battle of the Somme; explored the development of medical treatment for wounded soldiers during the First World War.

- Robots (ended 2017).[27]

- The Sun: Living with our Star (ended 2019).[28]

- The Last Tsar: Blood and Revolution (ended 2019).[29]

- Top Secret: From Cyphers to Cyber Security (ended 2020, closed at the Science and Industry Museum on 31 August 2021).[30]

- Art of Innovation – from Enlightenment to Dark Matter (2019–2020) – explored the interaction between science, the arts and society; included artworks by Boccioni, Constable, Hepworth, Hockney, Lowry and Turner.[31]

- Science Fiction: Voyage to the Edge of Imagination (2022–2023) [32]

- The Science Box contemporary science series toured various venues in the UK and Europe in the 1990s and from 1995 The Science of Sport appeared in various incarnations and venues around the World. In 2005 The Science Museum teamed up with Fleming Media to set up The Science of... to develop and tour exhibitions including The Science of Aliens,[33] The Science of Spying[34] and The Science of Survival.[35]

- In 2008, The Science of Survival exhibition opened to the public and allowed visitors to explore what the world might be like in 2050 and how humankind will meet the challenges of climate change and energy shortages.

- In 2014 the museum launched the family science Energy Show, which toured the country.[36]

- The same year it began a new programme of touring exhibitions which opened with Collider: Step inside the world's greatest experiment to much critical acclaim. The exhibition takes visitors behind the scenes at CERN and explores the science and engineering behind the discovery of the Higgs Boson. The exhibition toured until early 2017.

- Media Space exhibitions also go on tour, notably Only in England which displays works by the photographers Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr.

Events

[edit]Astronights for Children

[edit]The Science Museum organises Astronights, "all-night extravaganza with a scientific twist". Up to 380 children aged between 7 and 11, accompanied by adults, are invited to spend an evening performing fun "science based" activities and then spend the night sleeping in the museum galleries amongst the exhibits. In the morning, they're woken to breakfast and more science, watching a show before the end of the event.[37]

'Lates' for Adults

[edit]On the evening of the last Wednesday of every month (except December) the museum organises an adults only evening with up to 30 events, from lectures to silent discos. Previous Lates have seen conversations with the actress activist Lily Cole[38] and Biorevolutions with the Francis Crick Institute which attracted around 7000 people, mostly under the age of 35.[39]

Cancellation of James D. Watson talk

[edit]In October 2007, the Science Museum cancelled a talk by the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, James D. Watson, because he claimed that IQ test results showed black people to have lower intelligence than white people. The decision was criticised by some scientists, including Richard Dawkins,[40] but supported by other scientists, including Steven Rose.[41]

Former galleries

[edit]

The museum has undergone many changes in its history with older galleries being replaced by new ones.

- The Children's Gallery – 1931–1995 Located in the basement, it was replaced by the under fives area called The Garden.[42]

- Agriculture – 1951–2017 Located on the first floor, it looked at the history and future of farming in the 20th century. It featured model dioramas and object displays. It was replaced by Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries in 2019.[43]

- Shipping – 1963–2012. Located on the second floor, its contents were 3D scanned and made available online. It was replaced by Information Age.[44]*

- Land Transport – 1967–1996[45] Located on the ground floor, it displayed vehicles and objects associated with transport on land, including rail and road. It was replaced by the Making the Modern World gallery in 2000.

- Glimpses of Medical History – 1981–2015 Located on the fourth floor, it contained reconstructions and dioramas of the history of practised medicine. It was not replaced, but subsumed into Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries which opened on the museum's first floor in November 2019.[46]

- Science and the Art of Medicine – 1981–2015 Located on the fifth floor, which featured exhibits of medical instruments and practices from ancient days and from many countries. It was not replaced, but subsumed into Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries which opened on the museum's first floor in November 2019.[46]

- Launchpad – 1986–2015 Originally opening on the ground floor,[42] in 1989 it moved to the first floor replacing Textiles. Then in 2000 to the basement of the newly built Wellcome Wing. In 2007, it moved to its final location on the third floor, replacing the George III gallery.[47] It was replaced by Wonderlab in 2016.[48]

- Challenge of Materials – 1997–2019[49] Located on the first floor, explored the diversity and properties of materials. It was designed by WilkinsonEyre and featured an exhibit Materials House by Thomas Heatherwick.[50]

- Cosmos and Culture – 2009–2017[51][52] Located on the first floor, it featured astronomical objects showing the study of the night sky. It was replaced by Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries in 2019.

- Atmosphere – 2010–2022.[53][54] The Atmosphere gallery explored the science of climate.

- Engineer your Future – 2014–2023.[55] The Engineer your Future gallery explored whether you have the problem solving and team working skills to succeed in a career in engineering.

- The Secret Life of the Home – 1995–2024. The Secret Life of the Home showed the development of household appliances mostly from the late 19th and early 20th century, although some were earlier. This gallery closed permanently on 2 June 2024.[56]

Storage, library and archives

[edit]Blythe House, 1979–2019, the museum's former storage facility in West Kensington, while not a gallery, it offered tours of the collections housed there.[57] Objects formerly housed there are being transferred to the National Collections Centre, at the Science Museum Wroughton, in Wiltshire.[58]

The Science Museum has a dedicated library, and until the 1960s was Britain's National Library for Science, Medicine and Technology. It holds runs of periodicals, early books and manuscripts, and is used by scholars worldwide. It was, for a number of years, run in conjunction with the library of Imperial College, but in 2007 the library was divided over two sites. Histories of science and biographies of scientists were kept at the Imperial College Library until February 2014 when the arrangement was terminated, the shelves were cleared and the books and journals shipped out, joining the rest of the collection, which includes original scientific works and archives at the National Collections Centre.

Dana Research Centre and Library previously an event space and cafe, reopened in its current form in 2015. Open to researchers and members of the public, it allows free access to almost 7,000 volumes, which can be consulted on site.

Sponsorship

[edit]The Science Museum has been sponsored by major organisations including Shell, BP, Samsung and GlaxoSmithKline. Some have been controversial.[59] The museum declined to give details of how much it receives from oil and gas sponsors.[60] Equinor is also the title sponsor of "Wonderlab: The Equinor Gallery", an exhibition for children, while BP is one of the funding partners of the museum's STEM Training Academy.[61] Equinor's sponsorship of the Wonderlab exhibit was on the basis that the Science Museum would not make any statement to damage the oil firm's reputation.[62]

Shell has influenced how the museum presents climate change in its programme sponsored by the oil company.[63] The museum has signed a gagging clause in its agreement with Shell not to "make any statement or issue any publicity or otherwise be involved in any conduct or matter that may reasonably be foreseen as discrediting or damaging the goodwill or reputation" of Shell.[64]

The museum signed a sponsorship contract with the Norwegian oil and gas company Equinor which contained a gagging clause, stating the museum would not say anything that could damage the fossil fuel company's reputation.[65]

Reactions to sponsorship by fossil fuel companies

[edit]The museum's director, Ian Blatchford, defended the museum's sponsorship policy, saying: "Even if the Science Museum were lavishly publicly funded I would still want to have sponsorship from the oil companies."[60]

Scientists for Global Responsibility called the museum's move "staggeringly out-of-step and irresponsible".[66] Some presenters, including George Monbiot, pulled out of climate talks on finding they were sponsored by BP and the Norwegian oil company Equinor. Bob Ward of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment said the "carbon capture exhibition is not 'greenwash'".[67]

There have been protests against the sponsorship; in May 2021, a group calling themselves 'Scientists for XR' (Extinction Rebellion) locked themselves to a mechanical tree inside the museum.[68] The UK Student Climate Network carried out an overnight occupation in June 2021, and were threatened with arrest.[69][70] In August 2021, members of Extinction Rebellion held a protest inside and outside the museum with a 12 ft (3.7 m) pink dodo.[71]

In 2021, Chris Rapley, a climate scientist, resigned from the museum's advisory board because of oil and gas company sponsorship.[citation needed]

In 2021, more than 40 senior academics and scientists said they would not work with the Science Museum due to its financial relationships with the fossil fuel industry.[72]

In 2022, more than 400 teachers signed an open letter to the museum promising to boycott it following sponsorship of the museum's Energy Revolution exhibition by the coal mining company Adani.[73]

Directors of the Science Museum

[edit]The directors of the South Kensington Museum were:

- Henry Cole CB (1857–1873)

- Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen KCB KCMG CIE (1873–1893)

The directors of the Science Museum have been:

- Major-General Edward R. Festing CB FRS (1893–1904)

- William I. Last (1904–1911)

- Sir Francis Grant Ogilvie CB (1911–1920)

- Colonel Sir Henry Lyons FRS (1920–1933)[74]

- Colonel E. E. B. Mackintosh DSO (1933–1945)

- Herman Shaw (1945–1950)

- F. Sherwood Taylor (1950–1956)

- Sir Terence Morrison-Scott DSc FMA (1956–1960)

- Sir David Follett FMA (1960–1973)

- Dame Margaret Weston DBE FMA (1973–1986)

- Neil Cossons OBE FSA FMA (1986–2000)

- Lindsay Sharp (2000–2002)

The following have been head/director of the Science Museum in London, not including its satellite museums:

- Jon Tucker[75] (2002–2007, Head)

- Chris Rapley CBE (2007–2010)

The following have been directors of the National Museum of Science and Industry, (since April 2012 renamed the Science Museum Group) which oversees the Science Museum and other related museums, from 2002:

- Lindsay Sharp (2002–2005)

- Jon Tucker (2005–06, Acting Director)

- Martin Earwicker FREng (2006–2009)

- Molly Jackson (2009)

- Andrew Scott CBE (2009–10)

- Ian Blatchford (2010–)

References

[edit]- ^ "British Museum is the most-visited UK attraction again". BBC News. 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "ALVA – Association of Leading Visitor Attractions (2019)". alva.org.uk. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Science Museum | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "Museum history". About us. London: Science Museum. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Science Museum (museum, London, United Kingdom) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Construction". architecture.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014.

- ^ "Watt's workshop". Science Museum, London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Apollo 10". history.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Hollingham, Richard (8 September 2014). "V2: The Nazi rocket that launched the space age". BBC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Millard, Doug (8 September 2014). "V-2: The Rocket That Launched The Space Age". Science Museum Blog. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ a b Burns, Corrinne (13 December 2019). "Original Victorian pharmacy recreated in full at the Science Museum". Pharmaceutical Journal. 303 (7932). Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Wong, Henry (14 November 2019). "The Science Museum's £24 million exhibition gives medicine a human face". Design Week. Centaur Media plc. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Dobson, Juliet (2019). "The marvellous history of medicine". BMJ. 367 (367): l6603. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6603. PMID 31753815. S2CID 208226685. Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Mathematics: The Winton Gallery | Science Museum". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Zaha Hadid Architects' mathematics gallery opens at London Science Museum". Dezeen. 7 December 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "See and do". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Her Majesty The Queen sends her first tweet to unveil the Information Age". Blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Rooney, David (12 August 2010). "How did we get the planes in?". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Mission to Mercury : Bepi Columbo". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Driverless : Who's in control?". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "IMAX: The Ronson Theatre | Science Museum". sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Har-Even, Benny (28 December 2020). "Behind The Curtain At The London Science Museum IMAX". Forbes. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Codebreaker wins Great Exhibition award | Inside the Science Museum". Blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Unlocking Lovelock: Scientist, Inventor, Maverick". Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Robots". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "The Sun: Living with our star". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "The Last Tsar: Blood and Revolution". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Top Secret : From Cyphers to Cyber Security". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "The Art of Innovation: From Enlightenment to Dark Matter". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Science Fiction". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ McKie, Robin (27 August 2005). "They're aliens ... but not as we know them". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ "Unlock the secrets of the spying game". Times Online. 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008.

- ^ Cox, Antonia (4 April 2008). "Preparing for the future". This is London. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008.

- ^ "Science Museum Live: The Energy Show". Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Astronights". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Impossible trees grow in the Science Museums". 26 October 2013. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Record-breaking attendance at Crick event | The Francis Crick Institute". Crick.ac.uk. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ McKie, Robin; Harris, Paul (21 October 2007). "Disgrace: How a giant of science was brought low". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Rose, Steven (21 October 2007). "Watson's bad science". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b Science for the nation perspectives on the history of the Science Museum. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 2010. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-349-31119-4.

- ^ "Agriculture". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Shipping". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "Terrace Cuneo, National Railway Museum, York". York Press. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b Moorhead, Joanna (25 October 2019). "A journey through medicine: the new galleries at the Science Museum". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Anthony. "Launch Pad" (PDF). Science Projects. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Launchpad through the ages". Science Museum. Science Museum, London. 26 October 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Challenge of Materials Gallery". 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Materials House | Science Museum Group Collection". Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ "Cosmos and Culture opens astronomical show at Science Museum | Culture24". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Cosmos and Culture". Science Museum. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "New climate change gallery at the Science Museum". Science Museum Blog. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Atmosphere | Science Museum". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Engineer Your Future | Science Museum". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "The Secret Life of the Home | Science Museum". www.sciencemuseum.org.uk.

- ^ "Blythe House – About us – Science Museum London". Archived from the original on 6 September 2004. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "Our collection". Science Museum Group. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "George Monbiot pulls out of climate change talk at Science Museum over fossil fuel sponsors". inews.co.uk. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Science Museum defends oil and gas sponsorship". www.ft.com. 1 August 2019. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Oil sponsorship of the Science Museum". Culture Unstained. 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Science Museum sponsorship deal with oil firm included gag clause". The Guardian. 16 February 2023. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "Shell sought to influence direction of Science Museum climate programme". The Guardian. 31 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "Revealed: Science Museum signed gagging clause with exhibition sponsor Shell". Channel 4 News. 29 July 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Crisp, Wil (16 February 2023). "Science Museum sponsorship deal with oil firm included gag clause". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ "After staunch criticism, Science Museum defends oil company Shell's sponsorship of its climate exhibition". www.theartnewspaper.com. 20 April 2021. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ "The Science Museum's carbon capture exhibition is not 'greenwash' | Letter". The Guardian. 22 April 2021. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Sagir, Ceren (19 May 2021). "XR scientists lock themselves to a mechanical tree against a Science Museum exhibition sponsored by Shell". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Students protest at Science Museum over sponsorship by Shell". The Guardian. 19 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Science Museum climate protesters criticise 'intimidating' response". Museums Association. 22 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Extinction Rebellion activists glued to Science Museum site in Shell protest". The Guardian. 29 August 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Dozens of academics shun Science Museum over fossil fuel ties". The Guardian. 19 November 2021. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "Hundreds of teachers boycott Science Museum show over Adani sponsorship". The Guardian. 15 July 2022. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ The Rise of the Science Museum Under Henry Lyons. Science Museum. 1978. ISBN 9780901805195. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "Image of jon tucker, head of science museum, 2002. by Science & Society Picture Library". Scienceandsociety.co.uk. 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Albertopolis: Science Museum – architecture and history of the Science Museum

- sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk (SMG) – a group of British museums that includes the Science Museum

- Mapping the World's Science Museums from Nature Publishing Group's team blog Archived 2 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Science Museum, London

- Charities based in London

- Collection of the Science Museum, London

- Exempt charities

- Industry museums in England

- Musical instrument museums

- Medical museums in London

- Museums established in 1893

- Museums in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

- Science museums in London

- Steam museums in London

- Transport museums in London

- South Kensington

- 1857 establishments in England

- Science Museum Group

- Science museums in England