Names of the British Isles

The toponym "British Isles" refers to a European archipelago comprising Great Britain, Ireland and the smaller, adjacent islands.[1] The word "British" has also become an adjective and demonym referring to the United Kingdom[2] and more historically associated with the British Empire. For this reason, the name British Isles is avoided by some, as such usage could be interpreted to imply continued territorial claims or political overlordship of the Republic of Ireland by the United Kingdom.[3][4][5][6][7]

Alternative names that have sometimes been coined for the British Isles include "Britain and Ireland",[3][8][9] the "Atlantic Archipelago",[10] the "Anglo-Celtic Isles",[11][12] the "British-Irish Isles",[13] and the Islands of the North Atlantic.[14] In documents drawn up jointly between the British and Irish governments, the archipelago is referred to simply as "these islands".[15]

To some[according to whom?], the reasons to use an alternate name is partly semantic, while, to others, it is a value-laden political one.[16] The Channel Islands are normally included in the British Isles by tradition, though they are physically a separate archipelago from the rest of the isles.[17][18] United Kingdom law uses the term British Islands to refer to the UK, Channel Islands, and Isle of Man as a single collective entity.

An early variant of the term British Isles dates back to Ancient Greek times, when they were known as the Pretanic or Britannic Islands. It was translated as the British Isles into English in the late 16th or early 17th centuries by English and Welsh writers, whose writings have been described as propaganda and politicised.[19][20][21]

The term became controversial after the breakup of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1922. The names of the archipelago's two sovereign states were themselves the subject of a long dispute between the Irish and British governments.

History

[edit]Classical Antiquity

[edit]The earliest known names for the islands come from Greco-Roman writings. Sources included the Massaliote Periplus (a merchants' handbook from around 500 BC describing sea routes) and the travel writings of the Greek, Pytheas, from around 320 BC.[22][23] Although the earliest texts have been lost, excerpts were quoted or paraphrased by later authors. The main islands were called "Ierne", equal to the term Ériu for Ireland,[24] and "Albion" for present-day Great Britain. The island group had long been known collectively as the Pretanic or Britanic isles.

There is considerable confusion about early use of these terms and the extent to which similar terms were used as self-description by the inhabitants.[25] Cognates of these terms are still in use.[26]

According to T. F. O'Rahilly in 1946 "Early Greek geographers style Britain and Ireland 'the Pretanic (or Brettanic) islands', i.e. the islands of the Pritani or Priteni" and that "From this one may reasonably infer that the Priteni were the ruling population of Britain and Ireland at the time when these islands first became known to the Greeks".[27] O'Rahilly identified the Preteni with the Irish: Cruthin and the Latin: Picti, whom he stated were the earliest of the "four groups of Celtic invaders of Ireland" and "after whom these islands were known to the Greeks as 'the Pretanic Islands'".[28]

According to A. L. F. Rivet and Colin Smith in 1979 "the earliest instance of the name which is textually known to us" is in The Histories of Polybius, who referred to them as: τῶν αἱ Βρεταννικαί νήσοι, romanized: tōn hai Bretannikai nēsoi, lit. 'Brettanic Islands' or 'British Isles'.[29] According to Rivet and Smith, this name encompassed "Britain with Ireland".[29] Polybius wrote:

According to Christopher Snyder in 2003, the collective name "Brittanic Isles" (Greek: αἱ Βρεττανίαι, romanized: hai Brettaníai, lit. 'the Britains') was "a geographic rather than a cultural or political designation" including Ireland.[32] According to Snyder, "Preteni", a word related to the Latin: Britanni, lit. 'Britons' and to the Welsh: Prydein, lit. 'Britain', was used by southern Britons to refer to the people north of the Antonine Wall, also known as the Picts (Latin: Picti, lit. 'painted ones').[33] According to Snyder, "Preteni" was a probably from a Celtic term meaning "people of the forms", whereas the Latin name Picti was probably derived from the Celtic practice of tattooing or painting the body before battle.[33] According to Kenneth H. Jackson, the Pictish language was a Celtic language related to modern Welsh and to ancient Gaulish with influences from earlier non-Indo-European languages.[33]

The fourth chapter of the first book of the Bibliotheca historica of Diodorus Siculus describes Julius Caesar as having "advanced the Roman Empire as far as the British Isles" (Greek: προεβίβασε δὲ τὴν ἡγεμονίαν τῆς Ῥώμης μέχρι τῶν Βρεττανικῶν νήσων, romanized: proebíbase dè tḕn hēgemonían tês Rhṓmēs mékhri tôn Brettanikôn nḗsōn)[34] and in the 38th chapter of the third book Diodorus remarks that the region "about the British Isles" (τὸ περὶ τὰς Βρεττανικὰς νήσους, tò perì tàs Brettanikàs nḗsous) and other distant lands of the oecumene "have by no means come to be included in the common knowledge of men".[35] According to Philip Freeman in 2001, "it seems reasonable, especially at this early point in classical knowledge of the Irish, for Diodorus or his sources to think of all inhabitants of the Brettanic Isles as Brettanoi".[36]

According to Barry Cunliffe in 2002, "The earliest reasonably comprehensive description of the British Isles to survive from the classical authors is the account given by the Greek writer Diodorus Siculus in the first century B.C. Diodorus uses the word Pretannia, which is probably the earliest Greek form of the name".[25] Cunliffe argued that "the original inhabitants would probably have called themselves Pretani or Preteni", citing Jackson's argument that the form Pretani was used in the south of Britain and the form Preteni was used in the north.[37] This form then remained in use in the Roman period to describe the Picts beyond the Antonine Wall.[37] In Ireland, where Qu took the place of P, the form Quriteni was used.[37] Cunliffe argued that "Since it is highly probable that Diodorus was basing his description on a text of Pytheas's (though he nowhere acknowledges the fact), it would most likely have been Pytheas who first transliterated the local word for the islands into the Greek Prettanikē.[37] Pytheas may have taken his name for the inhabitants from the name Pretani when he made landfall on the peninsula of Belerion, though in Cunliffe's view, because it is unusual for a self-description (an endonym) to describe appearance, this name may have been used by Armoricans, from whom Pytheas would have learnt what the inhabitants of Albion were called.[37] According to Snyder, the Greek: Πρεττανοί, romanized: Prettanoí derives from "a Gallo-Brittonic word which may have been introduced to Britain during the P-Celtic linguistic innovations of the sixth century BC".[38]

According to Cunliffe, Diodorus Siculus used the spelling Prettanía, while Strabo used both Brettanía and Prettanía. Cunliffe argues the B spelling appears only in the first book of Strabo's Geography, so the P spelling reflects Strabo's original spelling and the changes to Book I are the result of a scribal error.[39] In classical texts, the word Britain (Greek: Pρεττανία, romanized: Prettanía or Bρεττανία, Brettanía; Latin: Britannia) replaced the word Albion. An inhabitant was therefore called a "Briton" (Bρεττανός, Brettanós; Britannus), with the adjective becoming "British" (Bρεττανικός, Brettanikós; Britannicus).[38]

The Pseudo-Aristotelian text On the Universe (Ancient Greek: Περὶ Κόσμου, romanized: Perì Kósmou; Latin: De Mundo) mentions the British Isles, identifying the two largest islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and stating that they are "called British" (Βρεττανικαὶ λεγόμεναι, Brettanikaì legómenai) when describing the ocean beyond the Mediterranean Basin:

—Pseudo-Aristotle, On the Universe, 393b.[40]

As explained by Pliny the Elder, this included the Orcades (Orkney), the Hæbudes (Hebrides), Mona (Anglesey), Monopia (Isle of Man), and a number of other islands less certainly identifiable from his names. The deduced Celtic name for Ireland – Iverio – from which its present name was derived, was known to the Greeks by the 4th century BC at least, possibly as early as the 6th century BC. The name meant "the fertile land". It was Latinised to Hiernia or Hibernia. Its people were the Iverni.[citation needed]

Around AD 70, Pliny the Elder, in Book 4 of his Naturalis Historia, describes the islands he considers to be "Britanniae" as including Great Britain, Ireland, Orkney, smaller islands such as the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, Anglesey, possibly one of the Frisian Islands, and islands which have been identified as Ushant and Sian[clarification needed]. He refers to Great Britain as the island called "Britannia", noting that its former name was "Albion". The list also includes the island of Thule, most often identified as Iceland—although some express the view that it may have been the Faroe Islands—the coast of Norway or Denmark, or possibly Shetland.[41] After describing the Rhine delta, Pliny begins his chapter on the British Isles, which he calls "the Britains" (Britanniae):

—Pliny the Elder, Natural History, IV.16.[42]

According to Thomas O'Loughlin in 2018, the British Isles was "a concept already present in the minds of those living in continental Europe since at least the 2nd–cent. CE".[43]

In his Orbis descriptio, Dionysius Periegetes mentions the British Isles and describes their position opposite the Rhine delta, specifying that there are two islands and calling them the "Bretanides" (Βρετανίδες, Bretanídes or Βρεταννίδες, Bretannídes).[29][44]

… αὐτὰρ ὑπ' ἄκρην |

... beneath |

| —Dionysius Periegetes, Orbis descriptio, lines 561–569.[44] |

In his Almagest (147–148 AD), Claudius Ptolemy referred to the larger island as Great Britain (Greek: Μεγάλη Βρεττανία, romanized: Megálē Brettanía) and to Ireland as Little Britain (Greek: Μικρά Βρεττανία, romanized: Mikrá Brettanía).[45] According to Philip Freeman in 2001, Ptolemy "is the only ancient writer to use the name "Little Britain" for Ireland, though in doing so he is well within the tradition of earlier authors who pair a smaller Ireland with a larger Britain as the two Brettanic Isles".[46] In the second book of Ptolemy's Geography (c. 150 AD), the second and third chapters are respectively titled in Greek: Κεφ. βʹ Ἰουερνίας νήσου Βρεττανικῆς θέσις, romanized: Iouernías nḗsou Brettanikê̄s thésis, lit. 'Ch. 2, position of Hibernia, a British island' and Κεφ. γʹ Ἀλβουίωνος νήσου Βρεττανικῆς θέσις, Albouíōnos nḗsou Brettanikê̄s thésis, 'Ch. 3, position of Albion, a British island'.[47]: 143, 146 Ptolemy wrote around AD 150, although he used the now-lost work of Marinus of Tyre from about fifty years earlier.[48] Ptolemy included Thule in the chapter on Albion; the coordinates he gives correlate with the location of Shetland, though the location given for Thule by Pytheas may have been further north, in Iceland or Norway.[49] Geography generally reflects the situation c. 100 AD.

Following the conquest of AD 43 the Roman province of Britannia was established,[50] and Roman Britain expanded to cover much of the island of Great Britain. An invasion of Ireland was considered but never undertaken, and Ireland remained outside the Roman Empire.[51] The Romans failed to consolidate their hold on the Scottish Highlands; the northern extent of the area under their control (defined by the Antonine Wall across central Scotland) stabilised at Hadrian's Wall across the north of England by about AD 210.[52] Inhabitants of the province continued to refer to themselves as "Brittannus" or "Britto", and gave their patria (homeland) as "Britannia" or as their tribe.[53] The vernacular term "Priteni" came to be used for the barbarians north of the Antonine Wall, with the Romans using the tribal name "Caledonii" more generally for these peoples who (after AD 300) they called Picts.[54]

The post-conquest Romans used Britannia or Britannia Magna (Large Britain) for Britain, and Hibernia or Britannia Parva (Small Britain) for Ireland. The post-Roman era saw Brythonic kingdoms established in all areas of Great Britain except the Scottish Highlands, but coming under increasing attacks from Picts, Scotti and Anglo-Saxons. At this time Ireland was dominated by the Gaels or Scotti, who subsequently gave their names to Ireland and Scotland.

In the grammatical treatise he dedicated to the emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180), De prosodia catholica, Aelius Herodianus notes the differences in spelling of the name of the British Isles, citing Ptolemy as one of the authorities who spelt the name with a pi (‹See Tfd›Greek: π, translit. p): "Brettanídes islands in the Ocean; and some [spell] like this with pi, Pretanídes, such as Ptolemy" (Βρεττανίδες νῆσοι ἐν τῷ Ὠκεανῷ· καὶ ἄλλοι οὕτως διὰ τοῦ π Πρετανίδες νῆσοι, ὡς Πτολεμαῖος, Brettanídes nêsoi en tôi Ōkeanôi; kaì álloi hoútōs dià toû p Pretanídes nêsoi, hōs Ptolemaîos).[55] Herodianus repeated this information in De orthographia: "Brettanídes islands in the ocean. They are called with pi, Pretanídes, such as by Ptolemy" (Βρεττανίδες νῆσοι ἐν τῷ ὠκεανῷ. λέγονται καὶ διὰ τοῦ π Πρετανίδες ὡς Πτολεμαῖος, Brettanides nēsoi en tō ōkeanōi. legontai kai dia tou p Pretanides hōs Ptolemaios).[56]

In the manuscript tradition of the Sibylline Oracles, two lines from the fifth book may refer to the British Isles:[57][58][59][60][61][62]

ἔσσεται ἐν Βρύτεσσι καὶ ἐν Γάλλοις πολυχρύσοις

ὠκεανὸς κελαδῶν πληρούμενος αἵματι πολλῷ·— Sibylline Oracles, Book V.

In the editio princeps of this part of the Sibylline Oracles, published by Sixt Birck in 1545, the Ancient Greek: Βρύτεσσι, romanized: Brýtessi or Brútessi is printed as in the manuscripts.[57] In the Latin translation by Sebastian Castellio published alongside Birck's Greek text in 1555, these lines are translated as:[57]

In Gallis auro locupletibus, atque Britannis,

Oceanus multo resonabit sanguine plenus:— Sibylline Oracles, Book V.

Castellio translated Βρύτεσσι as Latin: Britannis, lit. 'the Britains' or 'the British Isles'. The chronicler John Stow in 1580 cited the spelling of Βρύτεσσι in the Sibylline Oracles as evidence that the British Isles had been named after Brutus of Troy.[63] William Camden quoted these Greek and Latin texts in his Britannia, published in Latin in 1586 and in English in 1610, following Castelio's translation identifying Βρύτεσσι with the Britains or Britons:[64][65]

Twixt Brits and Gaules their neighbours rich, in gold that much abound,

The roaring Ocean Sea with bloud full filled shall resound.— William Camden, Britannia, 1610.[66]

In Aloisius Rzach's 1891 critical edition, the manuscript reading of Βρύτεσσι is retained.[58] Rzach suggested that Procopius of Caesarea referred to these lines when mentioning in his De Bello Gothico that the Sibylline Oracles "foretells the misfortunes of the Britons" (Ancient Greek: προλέγει τὰ Βρεττανῶν πάθη, romanized: prolégei tà Brettanôn páthē).[58] Milton Terry's 1899 English translation followed Rzach's edition, translating Βρύτεσσι as "the Britons":[59]

Among the Britons and among the Gauls

Rich in gold, Ocean shall be roaring loud

Filled with much blood; …— Sibylline Oracles, Book V.

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, however, suggested that the manuscript reading Βρύτεσσι should be emended to Βρύγεσσι, Brúgessi, in reference to the ancient Bryges.[60][62] Johannes Geffcken's 1902 critical edition accepted Wilamowitz's emendation, printing Βρύγεσσι.[60][62] John J. Collins's English text of the Sibylline Oracles in James H. Charlesworth's 1983 edition of translated Old Testament pseudepigrapha follows the manuscript tradition, translating Βρύτεσσι as "the Britains":[61][62]

Among the Britains and wealthy Gauls

the ocean will be resounding, filled with much blood, …— Sibylline Oracles, Book V.

Ken Jones, preferring Wilamowitz's emendation, wrote in 2011: "This is not, so far as I can see, a usual translation, nor is this even a Greek word. The Brygi (Βρύγοι) or Briges (Βρίγες), on the other hand, are a known people."[62]

The Divisio orbis terrarum mentioned the British Isles as the Insulae Britannicae or Insulae Britanicae.[29] The text refers to the archipelago together with Gallia Comata: "Gallia Comata, together with the Brittanic islands, is bounded on the east by the Rhine, …" (Latin: Gallia Comata cum insulis Brittanicis finitur ab oriente flumine Rheno, …).[67] According to the editor Paul Schnabel in 1935, the manuscript traditions spelt the name variously as: brittannicis, britannicis, or britanicis.[67]

The Ethnica of Stephen of Byzantium mentions the British Isles and lists the Britons as their inhabitants' ethnonym. He comments on the name's variable spelling, noting that Dionysius Periegetes spelt the name with a single tau and that Ptolemy and Marcian of Heraclea had spelt it with a pi:[68]

—Stephen of Byzantium, Ethnica, Β.169.

In Priscian's Latin adaptation of Dionysius Periegetes's Greek Orbis descriptio, the British Isles are mentioned as "the twin Britannides" (… geminae … Britannides).[69] The Hexaemeron of Jacob of Edessa twice mentions the British Isles (Classical Syriac: ܓܙܪ̈ܬܐ ܒܪܐܛܐܢܝܩܐܣ, romanized: gāzartāʾ Baraṭāniqās), and in both cases identifies Ireland and Great Britain by name:[70][71][72][73]

—Jacob of Edessa, Hexaemeron, III.12.

Middle Ages

[edit]At the Synod of Birr, the Cáin Adomnáin signed by clergymen and rulers from Ireland, Gaelic Scotland, and Pictland was binding for feraib Hérenn ocus Alban, 'on the men of Ireland and Britain'.[74] According to Kuno Meyer's 1905 edition, "That Alba here means Britain, not Scotland, is shown by the corresponding passage in the Latin text of § 33: 'te oportet legem in Hibernia Britaniaque perficere'".[74][75] The text of the Cáin Adomnáin describes itself: Iss ead in so forus cāna Adomnān for Hērinn ⁊ Albain, 'This is the enactment of Adamnan's Law in Ireland and Britain'.[74] The extent of the Cáin Adomnáin's jurisdiction in Britain is unclear; some scholars argue that its British domain was restricted to Dál Riata and Pictland,[76] while others write that it is simply unknown whether it was meant to apply to areas of Britain not under such strong Irish influence.[77]

In the Cosmography of Aethicus Ister, the British Isles are mentioned as having been visited by the protagonist (Dein insolas Brittanicas et Tylen navigavit, quas ille Brutanicas appellavit, ..., 'Then to the British islands and Thule he sailed, which are called the Brutanics').[78] In 1993, the editor Otto Prinz connected this name with the Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville,[78] in which it is stated: "Some suspect that the Britons were so named in Latin because they are brutes"[79] (Brittones quidam Latine nominatos suspicantur eo, quod bruti sint).[78]

In Arabic geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world, the British Isles are known as Jazāʾir Barṭāniya or Jazāʾir Barṭīniya. England was known as Ankarṭara, Inkiltara, or Lanqalṭara (French: l'Angleterre), Scotland as Sqūsiya (Latin: Scotia), and Ireland as Īrlanda or Birlanda.[80] According to Douglas Morton Dunlop, "Whether there was any Arab contact, except perhaps with Ireland, is, however, more than doubtful".[80] Arabic geographies mention the British Isles as twelve islands.[80] The Kitāb az-Zīj of al-Battānī describes the British Isles as the "islands of Britain" (Arabic: جزائر برطانية, romanized: Jazāʾir Barṭāniyah):[81][82]

—Al-Battānī, Kitāb az-Zīj.

The Kitāb al-Aʿlāq an-Nafīsa of Ahmad ibn Rustah describes the British Isles as the "twelve islands called Jazāʾir Barṭīnīyah" (Arabic: عشرة جزيرة تسمَّى جزائر برطينية, romanized: ʿashrah jazīrat tusammā Jazāʾir Barṭāniyah).[83][82] According to Dunlop, this "account of the British Isles follows al-Battāni's almost verbatim and is doubtless derived from it".[82]

In the 9th century, the Irish monk Dicuil mentioned the British Isles together with Gallia Comata: "Gallia Comata, together with the Brittanic islands, is bounded on the east by the Rhine, …" (Latin: Gallia Comata cum insulis Brittanicis finitur ab oriente flumine Rheno, ...).[84][85] He also describes the Faroe Islands as being two days' sailing from "the northernmost British Isles"[86] (a septentrionalibus Brittaniae insulis duorum dierum ac noctium recta navigatione, 'from the northern islands of Britain in a direct voyage of two days and nights').[84][85][87]

According to Irmeli Valtonen in 2008, on the so-called Cotton mappa mundi, an Anglo-Saxon mappa mundi based on the Old English Orosius, "The largest feature is the British Isles, which is indicated by the inscription Brittannia".[88]

The anonymous Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam describes the British Isles as the "twelve islands" (Persian: دوازده جزیره) which are "called Briṭāniya" (Persian: جزیرها برطانیه خوانند).[89][90][82]

The Kitāb at-Tanbīh wa'l-Ishrāf of al-Masʿūdī describes the British Isles as "the so-called Isles of Britain, twelve in number" (Arabic: الجزائر المسماة برطانية وفى اثنتا عشرة جزيرة, romanized: al-jazāʾir al-musammāh Barṭāniyah wa-fī ithnatā ʿashrah jazīrat).[91][82]

John Tzetzes mentioned the British Isles in the eighth book of his Chiliades as Αἱ Βρεττανίδες νῆσοι, hai Brettanídes nē̂soi, 'the Brettanides islands', describing them as "two of the greatest of all" (δύο αἱ μέγισται πασῶν, dyo hai mégistai pasō̂n) and naming them as Ἰουερνία, Iouernía and Ἀλουβίων, Aloubíōn.[92] According to Jane Lightfoot, John Tzetzes's conception of the British Isles was "two major islands plus thirty Orkneys and Thule near them".[44]

According to the University of Michigan's Middle English Dictionary, the Middle English word Britlond, Brutlond or Brutlonde (from the Old English: Brytland) could mean either "ancient Britain" or "the British Isles".[93] The noun Britoun (variously spelled Britton, Briton, Bryton, Brytoun, Bruton, Brutun, Brutin, Breton, Bretonn, or Britaygne) meant "a native of the British Isles".[94] The same word was also an adjective meaning "Brittonic, British" or "Breton".[94]

The English texts of the popular work Mandeville's Travels mention Great Britain in the context of the invention of the True Cross by Helena, mother of Constantine I, who was supposed to be a daughter of the legendary British king Coel of Colchester.[95] The so-called "Defective" manuscript tradition – the most widespread English version – spelled the toponym "Britain" in various ways. In the 2002 critical edition by M. C. Seymour based on manuscript 283 in the library of Queen's College, Oxford, the text says of Helena, in Middle English: … þe whiche seynt Elyn was moder of Constantyn emperour of Rome, and heo was douȝter of kyng Collo, þat was kyng of Engelond, þat was þat tyme yclepid þe Grete Brutayne, ….[95] In the 2007 edition by Tamarah Kohanski and C. David Benson based on manuscript Royal 17 C in the British Library, the text is: … Ingelond that was that tyme called the Greet Brytayne ….[96] The chronicler John Stow in 1575 and the poet William Slatyer in 1621 each cited the spelling of "Brutayne" or "Brytayne" in Mandeville's Travels as evidence that Brutus of Troy was the origin of the name of the British Isles.[97][98]

The Annals of Ulster describe Viking raids against the British Isles under the Latin entry for the year 793: Uastatio omnium insolarum Britannię a gentilibus, 'Devastation of all the islands of Britain by heathens' or 'a devastation of all the British isles by pagans'.[99][100][101] The surviving Early Modern English translation by Conall Mag Eochagáin of the since-lost Gaelic Annals of Clonmacnoise also describes this attack on the British Isles, but under the year 791: "All the Islands of Brittaine were wasted & much troubled by the Danes; this was thiere first footing in England."[102][100] According to Alex Woolf in 2007, the report in the Annals of Ulster "has been interpreted as a very generalised account of small-scale raids all over Britain" but that argues that "Such generalised notices … are not common in the Irish chronicles". Woolf compares the Annals of Ulster's "islands of Britain" with the "islands of Alba" mentioned by the Chronicon Scotorum.[103] The Chronicon describes Muirchertach mac Néill's attack on the "islands of Alba" (Irish: hinsib Alban) under the entry for the year 940 or 941:[103] Murcablach la Muircertach mac Néll go ttug orgain a hinsib Alban, 'A fleet was fitted out by Muircertach, son of Niall, and he brought plunder from the islands of Alba.'[104] According to Woolf, "This latter entry undoubtedly refers to the Hebrides".[103] Woolf argues that "It seems likely that the islands of Alba/Britain was the term used in Ireland specifically for the Hebrides (which makes very good sense from the perspective of our chroniclers based in the northern half of Ireland)".[103] The Annals of the Four Masters's report on the death of Fothad I under the year 961 describes him as Fothaḋ, mac Brain, scriḃniḋ ⁊ espucc Insi Alban, 'Fothadh, son of Bran, scribe and Bishop of Insi-Alban'.[105] John O'Donovan's 1856 edition glossed "Insi-Alban" as "the islands of Scotland".[105] According to Woolf in 2007, this "is the latest use of the term 'Islands of Alba' for the Hebrides (probably just the islands from Tiree south)".[103] According to Alasdair Ross in 2011, the "islands of Alba" are "presumably the Western Isles".[106]

Early Modern Period

[edit]Michael Critobulus, in his History's dedicatory letter to Mehmed II (r. 1444–1481), expressed his hope that by writing in Greek his work would have a wide audience, including "those who inhabit the British Isles" (Greek: τοῖς τὰς Βρετανικὰς Νήσους οἰκοῦσι, romanized: toîs tàs Bretanikàs Nḗsous oikoûsi).[107][108] According to Charles T. Riggs in 1954, Critobulus "distinctly states that he hopes to influence the Philhellenes in the British Isles by this story of a Turkish sultan".[108]

John Skelton's English translation of Poggio Bracciolini's Latin translation of Diodorus Siculus's preface to his Bibliotheca historica, written in the middle 1480s, mentions the British Isles as the yles of Bretayne.[109]

Andronikos Noukios, a Greek writing under the pen name Nikandros Noukios (Latin: Nicander Nucius), visited Great Britain in the reign of Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) as part of an embassy. In his account, he describes the British Isles as having taken their name from colonists from Brittany, rather than the other way around.[110] He wrote:

[[File:Egnazio Danti - British Isles - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|Ignazio Danti's map of the British Isles from the Florentine Palazzo Vecchio's [[Palazzo Vecchio#Stanza delle Mappe geografiche o Stanza della Guardaroba|Stanza delle Mappe geografiche]], 1565:

Isole Britaniche

Lequalico tengano il regno di Inghilterra et di Scotia con l'Hibernia

]] The term "British Isles" entered the English language in the late 16th century to refer to Great Britain, Ireland and the surrounding islands. In general, the modern notion of "Britishness" evolved after the 1707 Act of Union.[113]

By the middle of the 16th century the term appears on maps made by geographers including Sebastian Münster.[114] Münster in Geographia Universalis, 'Universal Geography' (a 1550 reissue of Ptolemy's Geography) uses the heading De insulis Britannicis, Albione, quæ est Anglia & Hibernia, & de ciuitatibus earum in genere, 'Of the Britannic islands, Albion, which is England, and Ireland, and of their cities in general'.[115] Gerardus Mercator produced much more accurate maps, including one of the Insulæ Britannicæ, 'British islands' in 1564.[115][116]

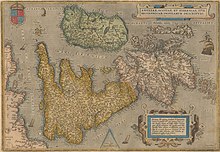

Abraham Ortelius, in his atlas of 1570 (Theatrum Orbis Terrarum), uses the title Angliae, Scotiae et Hiberniae, sive Britannicar. insularum descriptio, 'A description of England, of Scotland, and of Ireland, or of the Britannic islands'.[117]: 605 According to Philip Schwyzer, "This is among the very first early modern references to the 'British Isles', a term used anciently by Pliny but rarely in the medieval period or earlier in the sixteenth century".[117]: 605

Thomas Twyne's English translation of Dionysius Periegetes's Orbis descriptio, published in 1572, mentions the British Isles as the Iles of Britannia.[118]

John Stow, citing Aethicus Ister, Mandeville's Travels, and Geoffrey of Monmouth, described the naming of Great Britain and the British Isles by Brutus of Troy (Early Modern English: Brute) in his 1575 work A Summarie of the Chronicles of England.[119] According to Stow's second chapter, Brutus:[97]

... aryved in this Ilande, whyche was called Albion, at a place now called Totnes in Devonshire, the yere of the world. 2855. the yeare before Christs nativitie. 1108. wherein he first began to raigne, and named it Britaine, (as some write) or rather after his owne name Brutaine, as Æthicus that wonderfull Philosopher (a Scithian by race, but an Istrian by countrey) translated by saint Hierome above a thousand yeares past, termeth both it and the Iles adiacent Insulas Britanicas. And for more proufe of this restored name, not only the sayde Philosopher (who travelled through many lands, and in this lande taught the knowledge of minerall works) maye be alledged, but sundrie other: & some English wryters above an hundred yeares since, usually do so name it, and not otherwise, through a large historie of this land, translated out of Frenche.

— John Stow, A Summarie of the Chronicles of England, 1575, page 17–18.

The 1580 edition of Stow's work spelled the Latin name Insulas Brutannicas and the English names Brutan and the Brytaines, and additionally cited the authority of the Sibylline Oracles for the conflation of the Latin letter Y with the ‹See Tfd›Greek: υ or Υ (upsilon):[63]

... the Sybils Oracles, who in the name of the Brytaines is written with y. that is the Greekes little u. whyche Oracles althoughe they were not the Sibils owne worke, as some suspecte, yet are they very antient indeede, and that they might seeme more auntient, use the moste auntient name of Countreys and peoples

— John Stow, A Summarie of the Chronicles of England, 1580, page 17–18.

Schwyzer states that Raphael Holinshed's 1577 Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland is the first work of historiography to deal with the British Isles in particular; "To the best of my knowledge, no book published in England before 1577 specified in its title a scope at once inclusive of and restricted to England, Scotland, and Ireland".[117]: 594 According to Holinshed himself in the second chapter (Of the auncient names of this Islande) of the first book (An Historicall Description of the Islande of Britayne, with a briefe rehearsall of the nature and qualities of the people of Englande, and of all such commodities as are to be founde in the same) of the first volume of the Chronicles, Brutus had both renamed Albion after himself and given his name to the British Isles as a whole:

... Brute, who arriving here in the 1127, before Christ, and 2840. after the creation, not onely chaunged it into Britayne (after it had bene called Albion, by the space of 595. yeares) but to declare his sovereigntie over the reast of the Islandes also that are about the same, he called them all after the same maner, so that Albion was sayde in tyme to be Britanniarum insula maxima, that is, the greatest of those Isles that bare the name of Britayne.

— Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1577, Volume I, chapter 2, page 2.

Eryn:

Hiberniae,

Britannicae

Insulæ, Nova

Descriptio

Irlandt

The geographer and occultist John Dee (of Welsh ancestry)[120] was an adviser to Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) and prepared maps for several explorers. He helped to develop legal justifications for colonisation by Protestant England, breaking the duopoly the Pope had granted to the Spanish and Portuguese Empires. Dee coined the term "British Empire" and built his case, in part, on the claim of a "British Ocean"; including Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland and (possibly) North America, he used alleged Saxon precedent to claim territorial and trading rights.[121] According to Ken MacMillan, "his imperial vision was simply propaganda and antiquarianism, without much practical value and of limited interest to the English crown and state."[121] The Lordship of Ireland had come under tighter English control as the Kingdom of Ireland, and diplomatic efforts (interspersed with warfare) tried to bring Scotland under the English monarch as well.[121][verification needed]

Dee used the term "Brytish Iles" in his General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to Perfecte Arte of Navigation of 1577.[122] Dee also referred to the Imperiall Crown of these Brytish Ilandes, which he called an Ilandish Monarchy, and to the Brytish Ilandish Monarchy.[122] According to Frances Yates, Dee argued that the advice given by the Byzantine Neoplatonist philosopher Gemistos Plethon in two orations addressed to the emperor Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1373–1425) and his son Theodore II Palaiologos (r. 1407–1448) "on the affairs of the Peloponnesus and on ways and means both of improving the economy of the Greek islands and of defending them" should inform Elizabeth I's claims to territorial waters and adjacent territories.[123]: 47 Dee described these orations as "now published" – they had been translated into Latin by Willem Canter from a manuscript owned by János Zsámboky and published at Antwerp in 1575 by Christophe Plantin.[124][125] Dee wrote:

Moreover, (Sayd he) if it should not be taken in worse parte, of our soveraign, than, of the Emperour of Constantinople, Emanuel, the syncere Intent, and faythfull Advise, of Georgius Gemistus Pletho, was, I could (proportionally, for the occasion of the Tyme, and place,) frame and shape very much of Gemistus those his two Greek Orations, (the first, to the Emperor, and the Second to his Sonne, Prince Theodore:) for our brytish iles, and in better and more allowable manner, at this Day, for our People, than that his Plat (for Reformation of the State, at those Dayes, (could be found, for Peloponnesus, avaylable. But, Seeing those Orations, are now published: both in Greek and Latin, I need not Dowbt, but they, to whom, the chief Care of such causes is committed, have Diligently selected the Hony of those Flowres, already, for the Common-Wealths great Benefit.

— John Dee, General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to Perfecte Arte of Navigation, 1577.

According to Yates, "In spite of the difficulties of Dee's style and punctuation his meaning is clear" – Dee argued "that the advice given to the Byzantine Emperor by Pletho is good advice for Elizabeth, the Empress of Britain".[123]: 47 Dee believed that the British Isles had originally been called the "Brutish Isles", a name he had read in Aethicus Ister's Cosmography, which he thought was written in Classical Antiquity.[126]: 85–86 Invoking the Cosmography of Aethicus and its supposed translator Jerome, Dee argued that the British Isles had been misnamed, noting:[127]

St Hierome his admiration of ethicus his assert[ion] that these Iles of albion and irelande sho[ld] be called brutanicae & not britannicae

— John Dee, Of Famous and Rich Discoveries, 1577, British Library, Cotton MS. Vitellius. C. VII. art. 3, fols. 202 r–v.

According to Peter J. French, "Like Leland, Lhuyd and other antiquarians, Dee believed that it was mistakes in orthography and pronunciation that had confused the spelling of the name", which had come from the name of Brutus. The supposed alteration in spelling had caused:[127]

the [origin] all Di[s] coverer & Conqueror, and the very first absolute king of these Septentrionall brytish Islands, to be forgotten: or some wrong person, in undue Chronography, with repugnant circumstances, to be nominated in our brutus the italien trojan, his stede.

— John Dee, Of Famous and Rich Discoveries, 1577, British Library, Cotton MS. Vitellius. C. VII. art. 3, fols. 202 r–v.

In his copy of John Bale's Scriptorum illustrium maioris Brytanniae catalogus (later in Christ Church Library), at Bale's passage on Gildas, Dee had added an annotation on Brutus, stating: "Note this authority of Gildas concerning Brutus and Brytus, and remember that from the most ancient authority of the astronomer Aethicus, they were called the Brutish Islands" (Nota hanc Gildae authoritatem de Bruto et Bryto, et memor esto de Ethici astronomi authoritate antiquissima, insulas Brutanicas dictas esse)". He underlined Bale's words: "up to the entrance of Brutus, or rather Brytus" (usque ad Bruti, potius Bryti introitum).[126]: 97, note 48

In his Britannia, published in Latin in 1586, William Camden cited the Sibylline Oracles for evidence of the antiquity of Britain's toponym and of its origin in the name of the Britons, quoting both the Greek text published by Birck and the Latin translation by Castellio. Camden and Philemon Holland's 1610 English language edition of the work included the same arguments:

—William Camden, Britannia, 1607 and 1610 editions.[128][129]

According to John Morrill, at the time of the Union of the Crowns under the Stuart dynasty in the early 17th century, the historic and mythological relationship of Ireland and Great Britain was conceptualised differently to the relationship between the kingdoms of England and Scotland. While the British Isles was considered a geographic unit, the political debate on the Union involved the English and Scottish kingdoms, but not Ireland. James VI and I promoted political unity between Scotland ("North Britain") and England ("South Britain"), introducing the Union Flag and the title "King of Great Britain", but the same was not true of Ireland. Since the Middle Ages, Britain had been understood to be a historical unit once ruled by the legendary kings of Britain, of whom the first had been Brutus of Troy – as described in the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Unlike Wales, England, and Scotland, Ireland did not form part of this mythological concept, which was itself in decline by 1600.[130]

The Latin expression rex Britanniarum, 'king of the Britains' or 'king of the British Isles' was used by some panegyrists of James VI and I after his accession to the Anglo-Irish throne and his proclamation as "king of Great Britain".[131]: 199 Andrew Melville used the title for his 1603 Latin poem Votum pro Iacobo sexto Britanniarum rege, 'Vow for James the Sixth, king of the Britains'.[132]: 17 [133]: 22 Isaac Wake used the same title in his Latin poem on the king's August 1605 visit to Oxford: Rex platonicus: sive, De potentissimi principis Iacobi Britanniarum Regis, ad illustrissimam Academiam Oxoniensem, 'The Platonic king, or: On the most potent prince James, king of the Britains, to the most illustrious University of Oxford'.[131]: 199 For James's assumption of the triune British monarchy, Hugo Grotius composed his Inauguratio regis Brittaniarum anno MDCIII, 'Inauguration of the king of the Britains in the year 1603',[134] which extolled the historic naval powers of English kings and which was cited approvingly by John Selden in his 1635 work Mare Clausum: Of the Dominion, or, Ownership of the Sea.[135] Stanley Bindoff noted that the same title Rex Britanniarum was formally adopted in 1801.[131]: 199

In John Speed's 1611 Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, the cartographer refers to the islands as Britannish.[136] Before the first chapter, Speed introduces his map of the British Isles as "The British Ilands, proposed in one view in the ensuing map".

Speed describes the position of "the Iland of Great Britaine" as being north and east of Brittany, Normandy, and the other parts of the coast of Continental Europe:[137]

It hath Britaine, Normandy, and other parts of France upon the South, the Lower Germany, Denmarke, and Norway upon the East; the Isles of Orkney and the Deucaledonian Sea, upon the North; the Hebrides upon the West, and from it all other Ilands, and Ilets, which doe scatteredly environ it, and shelter themselves (as it were) under the shadow of Great Albion (another name of this famous Iland) are also accounted Britannish, & are therefore here described altogether

— John Speed, Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, 1611

In his 1621 verse work Palæ-Albion: The history of Great Britanie from the first peopling of this island to this present raigne of or happy and peacefull monarke K: James, William Slatyer described the British Isles as named "the Brutus Iles in Greeke Dialect". Slatyer explained this spelling of the name in a marginal note that, like Stow, cited Aethicus and Mandeville's Travels and the confusion between the Latin letter u and the Greek letter upsilon (ύψιλον):[98]

Æthicus translated by Saint Ierome, above 1000. yeares since, calleth them Insulas Brutanicas: the Greeks writing it by υψιλον, it soundeth our u. And the Welsh doe the like, as is seene in Brytys, by them pronounced Brutus: Also English Writers that are above an hundred yeares since, call it Brutaine. J. Mandevill.

— William Slatyer, Palæ-Albion, 1621, ode III, canto XIIII, page 81, note b.

One of the Oxford English Dictionary citations of "British Isles" was in 1621 (before the civil wars) by Peter Heylin (or Heylyn) in his Microcosmus: a little description of the great world[138] (a collection of his lectures on historical geography). Writing from his English political perspective, he grouped Ireland with Great Britain and the minor islands with these three arguments:[139]

- The inhabitants of Ireland must have come from Britain as it was the nearest land

- He notes that ancient writers (such as Ptolemy) called Ireland a Brttish Iland

- He cites the observation of the first-century Roman writer Tacitus that the habits and disposition of the people in Ireland were not much unlike the Brittaines[140]

Modern scholarly opinion[20][21] is that Heylyn "politicised his geographical books Microcosmus ... and, still more, Cosmographie" in the context of what geography meant at that time. Heylyn's geographical work must be seen as political expressions concerned with proving (or disproving) constitutional matters, and "demonstrated their authors' specific political identities by the languages and arguments they deployed." In an era when "politics referred to discussions of dynastic legitimacy, of representation, and of the Constitution ... [Heylyn's] geography was not to be conceived separately from politics."

Geoffrey Keating, in his Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, discussed the mention of druids from the British Isles in Gaul in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, suggesting that the island Caesar had in mind was Ireland or Manainn – Anglesey or the Isle of Man.[141][142][143][144] John O'Mahony's 1866 translation was "from the British Isles",[142] as were the translations of John Barlow in 1811 and of Dermod O'Connor in 1723.[143][144] Patrick S. Dinneen's 1908 edition translates Keating's Irish: ó oiléanaibh na Breatan as "from the islands of Britain".[141]

—Geoffrey Keating, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, c. 1634, I.19–20.[141]

Robert Morden, in his 1680 Geography Rectified, introduced his map and chapter detailing the British Isles by noting their political unity under a single monarch but their continued separation into three kingdoms, with each of the British Isles beyond Great Britain and Ireland belonging to one of the three mainland kingdoms.[145]

Under this Title are Comprehended several distinct and famous Islands, the whole Dominion whereof (now United) is under the Command of the King of Great Britain, &c. Bounded on the North and West with the Hyperborean and Ducalidonean Ocean, on the South divided from France with the English Channel, on the East seperated [sic] from Denmark and Belgia with the British (by some call'd the German) Ocean; But on all sides environed with Turbulent Seas, guarded with Dangerous Rocks and Sands, defended with strong Forts, and a Potent Navy; Of these Islands one is very large, formerly called Albion, now great Britain, comprehending two Kingdoms, England and Scotland; and another of lesser extent makes one Kingdome called Ireland: The other smaller adjacent Isles are comprehended under one or other of these 3 Kingdoms, according to the Situation and Congruity with them.

— Robert Morden, Geography Rectified: or, a Description of the World, 1680, page 13.

Reception

[edit]Perspectives in Great Britain

[edit]In general, the use of the term British Isles to refer to the archipelago is common and uncontroversial within Great Britain,[146] at least since the concept of "Britishness" was gradually accepted in Britain.[147][148] In Britain it is commonly understood as being a politically neutral geographical term, although it is sometimes used to refer to the United Kingdom or Great Britain alone.[149][150][151][147] In the 2016 Oxford Dictionary Plus Social Sciences, Howard Sargeant describes the British Isles as "A geographical rather than a political designation".[152]

In 2003, Irish newspapers reported a British Government internal briefing that advised against the use of "British Isles".[153][154] There is evidence that its use has been increasingly avoided in recent years in fields like cartography and in some academic work, such as Norman Davies's history of Britain and Ireland The Isles: A History. As a purely geographical term in technical contexts (such as geology and natural history), there is less evidence of alternative terms being chosen.

According to Jane Dawson, "Finding an acceptable shorthand geographical description for the countries which formed the UK before the creation of Eire has proved difficult" and in her 2002 work on Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542–1567) and Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll, she wrote: "for convenience, I have used the following as virtual synonyms: the islands of Britain; these islands; the British Isles, and the adjective, British. Without intending to imply any hidden imperial or other agenda, they describe the kingdoms of Ireland, Scotland, and England and Wales as they existed in the sixteenth century".[155]

In the 2005 Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names, John Everett-Heath defined the British Isles as "Until 1949 a collective title ... In 1949 the Republic of Ireland left the British Commonwealth and so could no longer be included in the title".[156][157] Everett-Heath used the name in a "general note" and in the introduction to the same work.[156][158][159]

In the 2005 preface to the second edition of Hugh Kearney's The British Isles: A History of Four Nations, published in 2006, the historian noted that "The title of this book is 'The British Isles', not 'Britain', in order to emphasise the multi-ethnic character of our intertwined histories. Almost inevitably many within the Irish Republic find it objectionable, much as Basques or Catalans resent the use of the term 'Spain'."[160] and illustrated this by quoting the objection of Irish poet Seamus Heaney to being included in an anthology of British poems. Kearney also wrote: "But what is the alternative to 'The British Isles?' Attempts to encourage the use of such terms as 'The Atlantic Archipelago' and 'The Isles' have met with criticism because of their vagueness. Perhaps one solution is to use 'the British Isles' in inverted commas".[160]

Recognition of issues with the term (as well as problems over definitions and terminology) was discussed by the columnist Marcel Berlins, writing in The Guardian in 2006. Beginning with "At last, someone has had the sense to abolish the British Isles", he opines that "although purely a geographical definition, it is frequently mixed up with the political entities Great Britain, or the United Kingdom. Even when used geographically, its exact scope is widely misunderstood". He also acknowledges that some view the term as representing Britain's imperial past, when it ruled the whole of Ireland.[161]

Perspectives in Ireland

[edit]Republic of Ireland

[edit]From the Irish perspective, some[162][163][6] consider "The British Isles" as a political term rather than a geographical name for the archipelago because of the Tudor conquest of Ireland, the subsequent Cromwellian activities in Ireland, the Williamite accession in Britain and the Williamite War in Ireland—all of which resulted in severe impact on the Irish people, landowners and native aristocracy. From that perspective, the term "British Isles" is not a neutral geographical term but an unavoidably political one.[164][better source needed] Use of the name "British Isles" is sometimes rejected in the Republic of Ireland, while claiming its use implies a primacy of British identity over all the islands outside the United Kingdom, including the Irish state and the Crown dependencies of the Isle of Man and Channel Islands.[165][166][162]

J. G. A. Pocock, in a lecture at the University of Canterbury in 1973 and published in 1974: "the term 'British Isles' is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously".[167][168] Nicholas Canny, professor of history at the National University of Ireland, Galway between 1979 and 2009, in 2001 described the term as "politically loaded" and stated that he avoided the term in discussion of the reigns following the Union of the Crowns under James VI and I (r. 1603–1625) and Charles I (r. 1625–1649) "not least because this was not a normal usage in the political discourse of the time".[169][163][170] Steven G. Ellis, however, Canny's successor as professor of history at the same university from 2009, wrote in 1996: "with regard to terminology, 'the British Isles', as any perusal of contemporary maps will show, was a widely accepted description of the archipelago long before the Union of the Crowns and the completion of the Tudor conquest of Ireland".[171][172] In the 2004 Brewer's Dictionary of Irish Phrase and Fable, Seán McMahon described "British Isles" as "A geographer's collective description of the islands of Britain and Ireland, but one that is no longer acceptable in the latter country" and "once acceptable" but "seen as politically inflammatory as well as historically inaccurate".[173][174] The same work describes Powerscourt Waterfall as "the highest in Ireland, and the second highest in the British Isles after Eas a' Chual Aluinn".[173]

Many political bodies, including the Irish government, avoid describing Ireland as being part of the British Isles.[citation needed] The journalist John Gunther, recollecting a meeting in 1936 or 1937 with Éamon de Valera, the president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, wrote that the Irish statesman queried his use of the term:[175]

My use of the term "British Isles" was an unconscious little slip. Mr. de Valera did not allow it to go uncorrected. Quite soberly he smiled and said that if I had meant to include Ireland in the British Isles, he trusted that I did so only as a "geographical expression." I explained that my chief duty to my newspaper was to gain knowledge, background, education. "Very well," Mr. de Valera said. "Let your instruction begin at once." And he set out to explain the difference between Ireland and the "British Isles." Some moments later, having again necessity to describe my field of operations, I sought a phrase and said, after a slight pause, "a group of islands in the northern part of Europe." Mr. de Valera sat back and laughed heartily. I hope he will not mind my telling this little story.

— John Gunther, Inside Europe, pp. 373–374

However, the term "British Isles" has been used by individual ministers, as did cabinet minister Síle de Valera when delivering a speech including the term at the opening of a drama festival in 2002,[176] and is used by government departments in relation to geographic topics.[177] In September 2005, Dermot Ahern, minister for foreign affairs, stated in a written answer to a parliamentary question from Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin in the Dáil Éireann: "The British Isles is not an officially recognised term in any legal or inter-governmental sense. It is without any official status. The Government, including the Department of Foreign Affairs, does not use this term."[178][179] Ahern himself continued to use the term, at a conference in April 2015 calling the 2004 Northern Bank robbery "The biggest bank raid in history of the British Isles".[180]

"British Isles" has been used in a geographical sense in Irish parliamentary debates by government ministers,[181][182] although it is often used in a way that defines the British Isles as excluding the Republic of Ireland.[183][184][185][186]

In October 2006, Irish educational publisher Folens announced that it was removing the term from its popular school atlas effective in January 2007. The decision was made after the issue was raised by a geography teacher. Folens stated that no parent had complained directly to them over the use of "British Isles" and that they had a policy of acting proactively, upon the appearance of a "potential problem".[187][188] This attracted press attention in the UK and Ireland, during which a spokesman for the Irish Embassy in London said, "'The British Isles' has a dated ring to it, as if we are still part of the Empire".[189] Writing in The Irish Times in 2016, Donald Clarke described the term as "anachronistically named".[190]

A bilingual dictionary website maintained by Foras na Gaeilge translates "British Isles" into Irish as Éire agus an Bhreatain Mhór "Ireland and Great Britain".[191][192] As the Irish translation of "British Isles", the 1995 Collins Gem Irish Dictionary edited by Séamus Mac Mathúna and Ailbhe Ó Corráin lists Na hOileáin Bhriotanacha, 'British islands'.[193]

Northern Ireland

[edit]Different views on terminology are probably most clearly seen in Northern Ireland (which covers six of the thirty-two counties in Ireland), where the political situation is difficult and national identity contested.[citation needed] In December 1999 at a meeting of the Irish cabinet and Northern Ireland Executive in Armagh. The first minister of Northern Ireland, David Trimble, told the meeting:

This represents the Irish government coming back into a relationship with the rest of the British Isles. We are ending the cold war that has divided not just Ireland but the British Isles. That division is now going to be transformed into a situation where all parts work together again in a way that respects each other.[194]

At a gathering of the British–Irish Inter-Parliamentary Body in 1998, sensitivity about the term became an issue. Referring to plans for the proposed British–Irish Council (supported by both Nationalists and Unionists), the British member of parliament (MP) Dennis Canavan, was paraphrased by official note-takers as having said in a caveat:

He understood that the concept of a Council of the Isles had been put forward by the Ulster Unionists and was referred to as a "Council for the British Isles" by David Trimble. This would cause offence to Irish colleagues; he suggested as an acronym IONA-Islands of the North Atlantic.[195]

In a series of documents issued by the United Kingdom and Ireland, from the Downing Street Declaration to the Good Friday Agreement (Belfast Agreement), relations in the British Isles were referred to as the "East–West strand" of the tripartite relationship.[196]

Alternative terms

[edit]There is no single accepted replacement of the term British Isles. However, the terms Great Britain and Ireland, British Isles and Ireland, Islands of the North Atlantic etc. are suggested.

British Isles and Ireland

[edit]The term British Isles and Ireland has been used in a variety of contexts—among others religious,[197] medical,[198] zoologic,[199] academic[200] and others. This form is also used in some book titles[201] and legal publications.[202]

Islands of the North Atlantic (or IONA)

[edit]In the context of the Northern Ireland peace process, the term "Islands of the North Atlantic" (and its acronym, IONA) was a term created by the British MP John Biggs-Davison.[14][203] It has been used as a term to denote either all the islands, or the two main islands, without referring to the two states.

IONA has been used by (among others) the former Irish Taoiseach (prime minister), Bertie Ahern:

The Government are, of course, conscious of the emphasis that is laid on the East-West dimension by Unionists, and we are, ourselves, very mindful of the unique relationships that exist within these islands – islands of the North Atlantic or IONA as some have termed them.[204]

Others have interpreted the term more narrowly to mean the "Council of the Isles" or "British-Irish Council". British MP Peter Luff told the House of Commons in 1998 that

In the same context, there will be a council of the isles. I think that some people are calling it IONA – the islands of the north Atlantic, from which England, by definition, will be excluded.[205]

His interpretation is not widely shared, particularly in Ireland. In 1997 the leader of the Irish Green Party Trevor Sargent, discussing the Strand Three (or East–West) talks between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, commented in the Dáil Éireann:

I noted with interest the naming of the islands of the north Atlantic under the acronym IONA which the Green Party felt was extremely appropriate.[206]

His comments were echoed by Proinsias De Rossa, then leader of the Democratic Left and later President of the Irish Labour Party, who told the Dáil, "The acronym IONA is a useful way of addressing the coming together of these two islands."[206]

Criticism

[edit]The neologism has been criticised on the grounds that it excludes most of the islands in the North Atlantic.[14]

The name is also ambiguous, because of the other islands in the North Atlantic which have never been considered part of the British Isles.[207]

West European Isles

[edit]The name "West European Isles" is one translation of the islands' name in the Gaelic languages of Irish[208] and Manx,[209] with equivalent terms for "British Isles".[210][211]

In Old Icelandic, the name of the British Isles was Vestrlönd, 'the Western lands'. The name of a person from the British Isles was a Vestmaðr, 'a man from the West'.[1][2]

Other terms

[edit]Alternative names include "Britain and Ireland",[3][8][9] the "Atlantic Archipelago",[10] the "Anglo-Celtic Isles",[11][12] and the "British-Irish Isles".[13]

These islands

[edit]Common among Irish public officials, although as a deictic label it cannot be used outside the islands in question.[212][213] Charles Haughey referred to his 1980 discussions with Margaret Thatcher on "the totality of relationships in these islands";[214] the 1998 Good Friday Agreement also uses "these islands" and not "British Isles".[213][215] In Brewer's Dictionary of Irish Phrase and Fable, McMahon writes that this is "cumbersome but neutral" and "the phrase in most frequent use" but that it is "cute and unsatisfactory".[173][174] In documents drawn up jointly between the British and Irish governments, the archipelago is referred to simply as "these islands".[15]

Insular

[edit]An adjective, meaning "island based", used as a qualifier in cultural history up to the early medieval period, as for example insular art, insular script, Insular Celtic, Insular Christianity.

Atlantic Archipelago

[edit]J. G. A. Pocock, in his lecture of 1973 entitled "British history: a Plea for a new subject" and published in 1974, introduced the historiographical concept of the "Atlantic archipelago – since the term 'British Isles' is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously".[167][168][216] It has been adopted by some historians.[216][217] According to Steven G. Ellis, in 1996 professor of history at the National University of Ireland, Galway, "to rename the British Isles as 'the Atlantic archipelago' in deference to Irish nationalist sensibilities seems an extraordinary price to pay, particularly when many Irish historians have no difficulty with the more historical term."[171] According to Jane Dawson in 2002, "Whilst accurate, the term 'Atlantic archipelago' is rather cumbersome".[155]

Hibernian Archipelago

[edit]Another suggestion is "Hibernian Archipelago". In Brewer's Dictionary of Irish Phrase and Fable, McMahon calls this title "cumbersome and inaccurate".[173][174]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b "British Isles". Encyclopedia Britannica. 4 February 2020.

British Isles, group of islands off the northwestern coast of Europe. The group consists of two main islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and numerous smaller islands and island groups,

- ^ a b Walter, Bronwen (2000). Outsiders Inside: Whiteness, Place, and Irish Women. New York: Routledge. p. 107.

A refusal to sever ties incorporating the whole island of Ireland into the British state is unthinkingly demonstrated in naming and mapping behaviour. This is most obvious in continued reference to 'the British Isles'.

- ^ a b c Hazlett, Ian (2003). The Reformation in Britain and Ireland: an introduction. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-567-08280-0.

At the outset, it should be stated that while the expression 'The British Isles' is evidently still commonly employed, its intermittent use throughout this work is only in the geographic sense, in so far as that is acceptable. Since the early twentieth century, that nomenclature has been regarded by some as increasingly less usable. It has been perceived as cloaking the idea of a 'greater England', or an extended south-eastern English imperium, under a common Crown since 1603 onwards. ... Nowadays, however, 'Britain and Ireland' is the more favoured expression, though there are problems with that too. ... There is no consensus on the matter, inevitably. It is unlikely that the ultimate in non-partisanship that has recently appeared the (East) 'Atlantic Archipelago' will have any appeal beyond captious scholars.

- ^ Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology by Judith Jesch 2003

- ^ Myers, Kevin (9 March 2000). "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times.

millions of people from these islands – oh how angry we get when people call them the British Isles

- ^ a b "Geographical terms also cause problems and we know that some will find certain of our terms offensive. Many Irish object to the term the 'British Isles';..." The Dynamics of Conflict in Northern Ireland: Power, Conflict and emancipation. Joseph Ruane and Jennifer Todd. Cambridge University Press. 1996

Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: Europe's House Divided 1490–1700. (London: Penguin/Allen Lane, 2003): "the collection of islands which embraces England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales has commonly been known as the British Isles. This title no longer pleases all the inhabitants of the islands, and a more neutral description is 'the Atlantic Isles'" (p. xxvi). On 18 July 2004, The Sunday Business Post Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine questioned the use of British Isles as a purely geographic expression, noting:

Retrieved 17 July 2006[The] "Last Post has redoubled its efforts to re-educate those labouring under the misconception that Ireland is really just British. When British Retail Week magazine last week reported that a retailer was to make its British Isles debut in Dublin, we were puzzled. Is not Dublin the capital of the Republic of Ireland?. When Last Post suggested the magazine might see its way clear to correcting the error, an educative e-mail to the publication...:

"... (which) I have called the Atlantic archipelago – since the term 'British Isles' is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously." Pocock, J. G. A. [1974] (2005). "British History: A plea for a new subject". The Discovery of Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 29. OCLC 60611042.

"... what used to be called the "British Isles", although that is now a politically incorrect term." Finnegan, Richard B.; Edward T. McCarron (2000). Ireland: Historical Echoes, Contemporary Politics. Boulder: Westview Press, p. 358."In an attempt to coin a term that avoided the 'British Isles' – a term often offensive to Irish sensibilities – Pocock suggested a neutral geographical term for the collection of islands located off the northwest coast of continental Europe which included Britain and Ireland: the Atlantic archipelago..." Lambert, Peter; Phillipp Schofield (2004). Making History: An Introduction to the History and Practices of a Discipline. New York: Routledge, p. 217.

"..the term is increasingly unacceptable to Irish historians in particular, for whom the Irish Sea is or ought to be a separating rather than a linking element. Sensitive to such susceptibilities, proponents of the idea of a genuine British history, a theme which has come to the fore during the last couple of decades, are plumping for a more neutral term to label the scattered islands peripheral to the two major ones of Great Britain and Ireland." Roots, Ivan (1997). "Union or Devolution in Cromwell's Britain". History Review.

- ^ The A to Z of Britain and Ireland by Trevor Montague "...although it is traditional to refer to the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as the British Isles, when considered as a single archipelago, this nomenclature implies a proprietary title which has long since ceased to exist, if indeed it ever really did exist. Despite the very close affinity between the British and Irish people I have no doubt that my title is both expedient and correct".

- ^ a b Davies, Alistair; Sinfield, Alan (2000), British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945–1999, Routledge, p. 9, ISBN 0-415-12811-0,

Many of the Irish dislike the 'British' in 'British Isles', while the Welsh and Scottish are not keen on 'Great Britain'. ... In response to these difficulties, 'Britain and Ireland' is becoming preferred usage although there is a growing trend amounts some critics to refer to Britain and Ireland as 'the archipelago'.

- ^ a b "Guardian Style Guide". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

British Isles: A geographical term taken to mean Great Britain, Ireland and some or all of the adjacent islands such as Orkney, Shetland and the Isle of Man. The phrase is best avoided, given its (understandable) unpopularity in the Irish Republic. Alternatives adopted by some publications are British and Irish Isles or simply Britain and Ireland

- ^ a b "...(which) I have called the Atlantic archipelago – since the term 'British Isles' is one which Irishmen reject and Englishmen decline to take quite seriously." Pocock, J. G. A. (2006). The Discovery of Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-85095-7.

- ^ a b D. A. Coleman (1982), Demography of immigrants and minority groups in the United Kingdom: proceedings of the eighteenth annual symposium of the Eugenics Society, London 1981, vol. 1981, Academic Press, p. 213, ISBN 0-12-179780-5,

The geographical term British Isles is not generally acceptable in Ireland, the term these islands being widely used instead. I prefer the Anglo-Celtic Isles, or the North-West European Archipelago.

- ^ a b Irish historical studies: Joint Journal of the Irish Historical Society and the Ulster Society for Irish Historical Studies, Hodges, Figgis & Co., 1990, p. 98,

There is much to be said for considering the archipelago as a whole, for a history of the British or Anglo-Celtic isles or 'these islands'.

- ^ a b John Oakland, 2003, British Civilization: A Student's Dictionary, Routledge: London

British-Irish Isles, the (geography) see BRITISH ISLES

British Isles, the (geography) A geographical (not political or CONSTITUTIONAL) term for ENGLAND, SCOTLAND, WALES, and IRELAND (including the REPUBLIC OF IRELAND), together with all offshore islands. A more accurate (and politically acceptable) term today is the British-Irish Isles.

- ^ a b c Ahern, Bertie (29 October 1998). "Address at 'The Lothian European Lecture' – Edinburgh". Department of the Taoiseach, Taoiseach's Speeches Archive 1998. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

[The Island of] Iona is a powerful symbol of relationships between these islands, with its ethos of service not dominion. Iona also radiated out towards the Europe of the Dark Ages, not to mention Pagan England at Lindisfarne. The British-Irish Council is the expression of a relationship that at the origin of the Anglo-Irish process in 1981 was sometimes given the name Iona, islands of the North Atlantic, and sometimes Council of the Isles, with its evocation of the Lords of the Isles of the 14th and 15th centuries who spanned the North Channel. In the 17th century, Highland warriors and persecuted Presbyterian Ministers criss-crossed the North Channel.

- ^ a b World and its Peoples: Ireland and United Kingdom, London: Marshall Cavendish, 2010, p. 8,

The nomenclature of Great Britain and Ireland and the status of the different parts of the archipelago are often confused by people in other parts of the world. The name British Isles is commonly used by geographers for the archipelago; in the Republic of Ireland, however, this name is considered to be exclusionary. In the Republic of Ireland, the name British-Irish Isles is occasionally used. However, the term British-Irish Isles is not recognized by international geographers. In all documents jointly drawn up by the British and Irish governments, the archipelago is simply referred to as "these islands." The name British Isles remains the only generally accepted terms for the archipelago off the northwestern coast of mainland Europe.

- ^ Marsh, David (11 May 2010). "Snooker and the geography of the British Isles". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "British Isles: a geographical term for the islands comprising Great Britain and Ireland with all their offshore islands including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands."

- ^ Alan Lew; Colin Hall; Dallen Timothy (2008). World Geography of Travel and Tourism: A Regional Approach. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-7978-7.

The British Isles comprise more than 6,000 islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe, including the countries of the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland. The group also includes the United Kingdom crown dependencies of the Isle of Man, and by tradition, the Channel Islands (the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey), even though these islands are strictly speaking an archipelago immediately off the coast of Normandy (France) rather than part of the British Isles.

- ^ Ken MacMillan, 2001, "Discourse on history, geography, and law: John Dee and the limits of the British empire", in Canadian Journal of History, April 2001.

- ^ a b R. J. Mayhew, 2000, "Geography is Twinned with Divinity: The Laudian Geography of Peter Heylyn" in Geographical Review, Vol. 90, No. 1 (January 2000), pp. 18–34: "In the period between 1600 and 1800, politics meant what we might now term 'high politics', excluding the cultural and social elements that modern analyses of ideology seek to uncover. Politics referred to discussions of dynastic legitimacy, of representation, and of the Constitution. ... Geography books spanning the period from the Reformation to the Reform Act ... demonstrated their authors' specific political identities by the languages and arguments they deployed. This cannot be seen as any deviation from the classical geographical tradition, or as a tainting of geography by politics, because geography was not to be conceived separately from politics."

- ^ a b Robert Mayhew, 2005, "Mayhew, Robert (March 2005). "Mapping science's imagined community: geography as a Republic of Letters". The British Journal for the History of Science. 38 (1): 73–92. doi:10.1017/S0007087404006478. S2CID 145452323." in the British Journal of the History of Science, 38(1): 73–92, March 2005.

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 12,Ó Corráin 1989, p. 1

- ^ Cunliffe 2002, pp. 38–45, 94 The Massaliote Periplus describes a sea route south round the west coast of Spain from the promontory of Oestriminis (Cape Finisterre) back to the Mediterranean. The poem by Avienius makes used of it in describing the voyage of Himilco the Navigator, also incorporating fragments from 11 ancient writers including Pytheas. When Avienus says it's two days sailing from Oestriminis to the Holy Isle, inhabited by the Hierni, near Albion, this differs from the sailing directions of the Periplus and implies that Oestriminis is Brittany, a conflict explained if it had been taken by Avienus from one of his other sources.

- ^ Ó Corráin 1989, p. 1

- ^ a b Cunliffe 2002, p. 94

- '^ Cognates of Albion (normally referring only to Scotland) – Albion (archæic); Cornish: Alban; Irish: Alba; Manx: Albey; Scots: Albiane; Scottish Gaelic: Alba; Welsh: Yr Alban. Cognates of Ierne – Ireland; Cornish: Iwerdhon; Irish: Éire; Manx: Nerin; Scots: Irland; Scottish Gaelic: Éirinn; Welsh: Iwerddon though in English Albion is deliberately archæic or poetical. Cognates of Priteni – Welsh: Prydain; Briton and British'.

- ^ O'Rahilly 1946, p. 84

- ^ O'Rahilly 1946, pp. 15, 84

- ^ a b c d Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). The place-names of Roman Britain. Princeton University Press. pp. 63−64, 282. ISBN 978-0-691-03953-4.

- ^ Paton, W. R.; Walbank, F. W.; Habicht, Christian, eds. (2010) [1922]. Polybius: The Histories. Loeb Classical Library 137. Vol. II: Books 3–4. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 150–151. doi:10.4159/DLCL.polybius-histories.2010.

- ^ Büttner-Wobst, Theodor, ed. (1922). Polybii Historiae [The History of Polybius]. Vol. I. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. p. 208.

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 12

- ^ a b c Snyder 2003, p. 68

- ^ Oldfather, Charles Henry, ed. (1933). Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes. Loeb Classical Library 279 (in Ancient Greek and American English). Vol. I: Books I – II.34. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Oldfather, Charles Henry, ed. (1935). Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes. Loeb Classical Library 303 (in Ancient Greek and American English). Vol. II: Books II.35 – IV.58. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 194–195.

- ^ Freeman, Philip (2001). Ireland and the Classical World. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-292-72518-8.

- ^ a b c d e Cunliffe 2002, p. 95

- ^ a b Snyder 2003, p. 12

- ^ Cunliffe 2002, p. 94–95

- ^ Aristotle or Pseudo-Aristotle (1955). "On the Cosmos, 393b12". On Sophistical Refutations. On Coming-to-be and Passing Away. On the Cosmos. Translated by Forster, Edward Seymour; Furley, David J. William Heinemann, Harvard University Press. pp. 360–361. at the Open Library Project.DjVu

- ^ "The opinions as to the identity of ancient Thule have been numerous in the extreme. We may here mention six:

- The common, and apparently the best founded opinion, that Thule is the island of Iceland.

- That it is either the Ferroe group, or one of those islands.

- The notion of Ortelius, Farnaby, and Schœnning, that it is identical with Thylemark in Norway.

- The opinion of Malte Brun, that the continental portion of Denmark is meant thereby, a part of which is to the present day called Thy or Thyland.

- The opinion of Rudbeck and of Calstron, borrowed originally from Procopius, that this is a general name for the whole of Scandinavia.

- That of Gosselin, who thinks that under this name Mainland, the principal of the Shetland Islands, is meant.

- ^ Pliny the Elder (1942). "Book IV, chapter XVI". Naturalis historia [Natural History]. Vol. II. Translated by Rackham, Harris. Harvard University Press. pp. 195–196.

- ^ O'Loughlin, Thomas (2018). "Ireland". Brill Encyclopedia of Early Christianity. Vol. 4 (Isi - Ori) (Online ed.). doi:10.1163/2589-7993_EECO_SIM_00001698. ISSN 2589-7993.

- ^ a b c Lightfoot, J. L., ed. (2014). Dionysius Periegetes, Description of the Known World: With Introduction, Translation, & Commentary (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 228–229, 391. ISBN 978-0-19-967558-6. OCLC 875132507.

- ^ Claudius Ptolemy (1898). "Ἕκθεσις τῶν κατὰ παράλληλον ἰδιωμάτων: κβ',κε'" (PDF). In Heiberg, J.L. (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Opera quae exstant omnia. Vol. 1 Syntaxis Mathematica. Leipzig: in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Freeman, Philip (2001). Ireland and the Classical World. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-292-72518-8.

- ^ Stückelberger, Alfred; Grasshoff, Gerd, eds. (2017) [2006]. Klaudios Ptolemaios. Handbuch der Geographie: 1. Teilband: Einleitung und Buch 1-4 & 2. Teilband: Buch 5-8 und Indices (in Ancient Greek and German) (2nd ed.). Schwabe Verlag (Basel). ISBN 978-3-7965-3703-5.

- ^ Ó Corráin 1989

- ^ Breeze, David J.; Wilkins, Alan (2018). "Pytheas, Tacitus and Thule". Britannia. 49: 303–308. doi:10.1017/S0068113X18000223. ISSN 0068-113X. JSTOR 26815343.

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 34

- ^ Ó Corráin 1989, p. 3

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 46

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 54 refers to epigraphic evidence from those Britons at home and abroad who left Latin inscriptions.

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 68, Cunliffe 2002, p. 95

- ^ Lentz, August, ed. (1965) [1867]. Herodiani technici Reliquiae. Grammatici Graeci III.1.1 (in Ancient Greek and Latin). Hildesheim [Leipzig]: G. Olms (B. G. Teubner). p. 95.

- ^ August, Lentz, ed. (1965). Herodiani technici Reliquiae. Grammatici Graeci III.1.2 (in Ancient Greek and Latin). Hildesheim [Leipzig]: G. Olms (B. G. Teubner). p. 484.