British America

British America and the British West Indies[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1585–1783 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: God Save the King | |||||||||||||||||||||

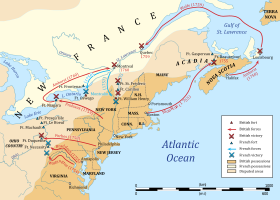

British colonies in continental North America (red) and the island colonies of the British West Indies of the Caribbean Sea (pink), after the French and Indian War (1754–1763) and before the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Colonies of England (1585–1707) Colonies of Scotland (1629–1632) Colonies of Great Britain (1707–1783) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy with various colonial arrangements | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1607–1625 (first) | James VI and I | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1760–1783 (last) | George III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1585 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1610 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Bermuda | 1614 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1620 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1632 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1655 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1670 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1713 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1763 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1775–1783 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1783 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pound sterling, Spanish dollar, bills of credit, commodity money, and many local currencies | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

British America collectively refers to various European colonies in the Americas prior to the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1783. The British monarchy of the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland—later named the Kingdom of Great Britain of the British Isles and Western Europe—governed many colonies in the Americas beginning in 1585. From 1607, numerous permanent settlements were made from Hudson Bay, to the Mississippi River and the Caribbean Sea.

Much of these territories were occupied by indigenous peoples, whose populations declined to epidemics, wars, and massacres. Africans were brought over in the Atlantic slave trade to aid with developing and farming the land as slaves or indentured servants. In 1664, England took the New Amsterdam colony in a war with the Dutch Republic. In the 1680s, frequent wars began between the British and the French over North American colonies. England and Scotland formed the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707.

In Queen Anne's War (1702—1713), Britain won Newfoundland and the Hudson Bay area from New France. In the Seven Years War (known in North America as French and Indian War (1754—1763)), the British won the eastern half of modern Canada, previously New France, and the Floridas from New Spain. In the American Revolutionary War (1775—1783), thirteen British colonies rebelled against the monarchy, forming the independent United States of America; Britain ceded the colonies and recognized the U.S. in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

The territories were formally named British America and the British West Indies briefly prior to 1783. "British North America" refers to British possessions in the Americas afterwards, such as Canada, but the term was only used after the 1839 Durham Report was published.

Background

[edit]Native American societies

[edit]Native Americans potentially have evidence of settlement in modern Illinois in as early as 5000 BCE, and in the Ohio River Valley in as early as 350 BCE. In the Hopewellian period from 200 BCE to 500 CE, numerous Native American tribes formed around what would later be New England due to ideal agricultural conditions. Major groups of this area include the Algonquian, Mohicans, Susquehannock, and Wyandot.

Around 1570 CE, in modern New York state, five native tribes—the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca peoples—formed a confederation ruled through participatory democracy, known as the Iroquois Confederacy. It was highly efficient at governing the region, and played an important part in the politics of later British and French colonies.[1]

European exploration and colonization

[edit]Around 1000 CE, two settlements on the modern Canadian island of Newfoundland were established by Norse viking explorers, but were soon abandoned. The next known European settlement in North America occurred some 500 years later.[2] In 1492, a Spanish expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean, on an island whose identity is disputed.[3] Christopher's brother, Bartholomew Columbus, founded the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola in 1496, the first European colony since the Norse's.[4] In 1526, Spain founded the San Miguel de Gauldape colony in either modern Georgia or the Carolinas. It lasted for a few months.[5]

In 1534, France explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence, starting fur trade with the natives, and eventually what became their colony New France.[6] In 1559, Spain founded a settlement at modern Pensacola, Florida, which was abandoned by 1561. In 1570, Spanish Jesuits founded the Ajacán Mission at Chesapeake Bay in modern Virginia, but they were killed by the local Powhatan people. In 1589 or 1599, a French colony was founded at Sable Island in Nova Scotia, but the colony had failed by 1603; another French colony at Saint Croix Island in modern Maine also existed from 1604 to 1607.[5] In 1604, near the Gulf of St. Lawrence, France started a new colony, later named Quebec.[6]

History

[edit]16th century

[edit]Roanoke Colony

[edit]In 1585, the English began their first settlement in North America, the Roanoke Colony. Its initial form only lasted until 1586 due to conflict with the local Native Americans.[7] In 1587, around 115 colonists led by Governor John White settled back at Roanoke.[8][7] White went back on a ship to England to get supplies for the colony, but his return was delayed by English's conflict with the Spanish Armada. In August 1590, White returned back to the colony, which had been abandoned. Left behind was an inscription on a post that said "CROATOAN" and a carving into a tree that said "CRO".[7] Where the colonists went to in those years is considered a mystery by some. However, "Croatoan" was an island south of Roanoke where Native Americans lived.[8]

17th century

[edit]A number of English colonies were established in America between 1607 and 1670 by individuals and companies whose investors expected to reap rewards from their speculation. They were granted commercial charters by Kings James I, Charles I, and Charles II, and by the Parliament of Great Britain. Later, most colonies were founded, or converted to, royal colonies.

Jamestown Colony

[edit]On 6 December 1606, three ships—the Discovery, Godspeed, and Susan Constant—left England to start a colony on the James River upstream from Chesapeake Bay. The settlement, known as the Jamestown Colony, was the first permanent English settlement in North America. It invested into by the Virginia Company English trading company. The site fit criteria given by the Virginia Company: it was inland and surrounded by water on three sides, which made it defensible against a potential Spanish naval attack; it was not inhabited by local Native Americans; and the water around the shore was deep enough so the English ships could be tied at the shoreline.[9][10][11]

Jamestown, established on May 14, 1607, was the start of the Virginia Colony, and was the colony's capital until 1699. Edward Maria Wingfield was made the colony's first president, and governed with six council members. The colonists suffered from diseases, famines, and wars with the Powhatan. Some Powhatan helped the colonists, and without them, the colony likely would have failed. In 1612, Englishman John Rolfe arrived in Jamestown, and introduced tobacco farming there. Tobacco made the colony profitable for the Virginia Company. In 1619, Virginia governor George Yeardley introduced a representative legislative assembly to the government. The town expanded in the 1620s.[9][10][11]

Popham Colony

[edit]In August 1607, 100 English settlers, men and boys, landed at present-day Phippsburg, Maine, with the goal of establishing the Popham Colony, building a fort and ships there. However, as they arrived in August, they came too late to plant crops, and when they started running out of food, some of them returned to England. The colony's leader, George Popham, died in February 1608. His successor, Raleigh Gilbert, learned that he had inherited his father's estate in England, and returned home in autumn 1608. The other colonists followed him back.[12][13]

Anglo-Powhatan Wars

[edit]

Thirty Powhatan tribes were organized under the Powhatan Confederacy, led by chief Powhatan. Chief Powhatan initially thought the English could be good allies and help defend them from other native tribes and the Spanish. Relations worsened when the English demanded the Powhatan give them more land to grow tobacco. In three wars, the Powhatan lost more land: the first from 1610 to 1614, the second from 1622 to 1626, and the third from 1644 to 1646. The Powhatan were subject to more lifestyle restrictions placed upon them by the English. The third war ended when chief Powhatan's successor, Opechanacanough, was captured and killed by Necotowance—who became the new successor. However, Necotowance signed a peace treaty with the British which effectively ended the confederacy. The Powhatan lost more land to the English over the next decades.[14][15]

Bermuda settlement

[edit]In 1511, the island of "Bermudas", later named Bermuda, was present on a Spanish map, possibly having been spotted as early as 1503. In 1609, 150 English people traveling on the Sea Venture, a Virginia Company ship on course to Jamestown, were shipwrecked on Bermuda by a hurricane. At the time, the English named it the "Somers Isles" after the travelers' leader, George Somers. This started a permanent English settlement in Bermuda. Most of them continued onto Jamestown, leaving three people behind on Bermuda until a Virginia Company charter in 1612 brought 60 more people to the island. The Virginia Company governed Bermuda until 1684.[16]

Plymouth Colony

[edit]In 1620, a hundred European Pilgrims, men and women, sailed to New England, establishing the permanent Plymouth settlement in modern Massachusetts. Forty of them were a part of the English Separatist Church, a radical faction of Puritan Protestants; they had moved from England to the Dutch Republic more than a decade prior, and then went to America seeking religious freedom. The first Pilgrim ship, the Mayflower, landed at Plymouth Rock in December. More than half of the colonists died in the first winter, but ultimately made a thriving, mostly self-sufficient colony. They also made peace treaties with the local Native American tribes, and in autumn 1621, the Pilgrims and Wampanoag shared a harvest feast which was the origin of the annual American holiday, Thanksgiving. Three other European ships traveled to Plymouth soon after, the Fortune in 1621, and the Anne and the Little James in 1622. All adult males on the Mayflower signed the Mayflower Compact, which wrote the first set of laws for the colony.[17][18]

Slaves and indentured servants

[edit]

From the 16th to 19th centuries, in the Atlantic slave trade, European powers—the Dutch Republic, England, France, Portugal, and Spain—transported 10 to 12 million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to work as slaves in the Americas.[19] In 1619, a group of twenty Africans were landed in Virginia, the first African-Americans. They were either slaves, those forced to work against their will and without pay; or indentured servants, those indebted to an employer for a limited time—the latter includes those who consented to the work or not. Both were true in this instance, as the group was forced to work and without pay and later freed.[20][21] Some European Americans were also indentured servants in English America.[20]

In 1641, Massachusetts became the first English colony in North America legalize slavery. Virginia legalized it in 1661. More restrictive slave laws in the colonies were codified, and the amount of African slaves increased, especially in the 1660s.[20][21] Britannica writes: "the development of the belief that [Africans] were an “inferior” race with a “heathen” culture made it easier for whites to rationalize the enslavement of Black people. Enslaved Africans were put to work clearing and cultivating the farmlands of the New World." In total, 430,000 Africans were brought to the future territories of the United States.[20]

Province of Maryland

[edit]In 1632, Englishman George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore was granted a charter by English king Charles I to proprietary rights to an area east of the Potomac River—to be a home for Roman Catholics facing repression in England—in exchange for a share of the income made from the land. Before George Calvert could develop the land, he died, and his son Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore was given the charter. Cecilius officially established the Province of Maryland, named after Charles I's queen consort Henrietta Maria. In March 1634, Cecilius' younger brother Leonard Calvert landed the founding expedition of Maryland, a permanent settlement, at St. Clement's Island on the Potomac. This carefully chosen expedition of English Protestants and Catholics arrived at the island on the ships The Ark and the Dove. The Marylanders learned from the mistakes of the Virginians by establishing trading posts and farms and making peace with the local Native Americans. In 1639, Maryland received African slaves.[22][23]

Pequot War

[edit]

The Pequot War from 1636 to 1638 was between the Pequot people and English colonists with their Native American allies in New England. In the 1620s, the Pequot used "diplomacy, coercion, intermarriage, and warfare" to dominate the other natives in the Long Island—Connecticut River complex, in order to control the local fur and wampum trades. They also allied with the Dutch. The other native tribes sided with the English colonists when as they became more powerful and established the Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut colonies.[24][25]

The Pequot War's immediate cause was the murder of two English traders, Captain John Stone and John Oldham, allegedly by the Pequots' allies, the Western Niantic people. In 1636, Massachusetts Bay Colony governor Henry Vane sent John Endecott on an expedition to Block Island to demand the Western Niantic to surrender the traders' murderers. There, Endecott burned the Western Niantic people's villages, and then moved to a Pequot village where he did the same. The Pequot raided English settlements in retaliation. The tribes which were dominated by the Pequot sided with the English, as the Pequot tribe was destroyed. Of the around 3,000 Pequot who lived in the region before the war, only 200 were alive after it. Many of these deaths occurred on May 26, 1637, in the Mystic massacre, when an English militia, along with members of the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes, set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River, killing 700 Pequot people.[24][25]

Colonial administration

[edit]A state department in London known as the Southern Department governed all the colonies beginning in 1660 along with a committee of the Privy Council, called the Board of Trade and Plantations. In 1768, Parliament created a specific state department for America, but it was disbanded in 1782 when the Home Office took responsibility for the remaining possessions of British North America in Eastern Canada, the Floridas, and the West Indies.[26]

Occupation of New Amsterdam

[edit]In 1624, the Dutch West India Company, a chartered company of the Dutch Republic,[28] founded the colony of New Netherland, which included the territory of modern New York City, as well as parts of New Jersey, Long Island, and Connecticut. The colony's capital was New Amsterdam, which became New York City. In 1664, an English naval squadron under Colonel Richard Nicolls threatened the Dutch to give up New Amsterdam. The Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant wanted to resist the English, but he was not popular enough to be supported in that. He surrendered the city on February 9, 1664, and the English renamed it "New York" soon after. The English and Dutch lived peacefully there. The city was returned to the Dutch in 1673, before going back to the English in 1674.[29]

King Philip's War

[edit]King Philip's War, in New England from 1675 to 1676, was between some Native American tribes (the Narragansett, Nashaway, Nipmuc, Podunk, and Wampanoag peoples, as well as the Wabanaki Confederacy) and English colonists with their own native allies (the Mohawk, Mohegan, and Pequot). Opposition to the English was led by Wampanoag chief Metacom. The war started with the murder of John Sassamon, a native who was Metacom's advisor and English language interpreter; before his murder, he was accused by Metacom of spying for the English. The murder escalated tensions between the natives and English over land disputes. In June 1675, the Plymouth Colony executed three Wampanoag who were found guilty of murdering Sassamon. King Philip's War took place in modern Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The English and their allies won, and most of their opposition was killed in the war or sold into slavery or indentured servitude.[30][31][32]

King William's War

[edit]The Nine Years War from 1689 to 1697 was a conflict in Europe between France and an alliance of England and the Dutch Republic. They fought—as members of either the House of Bourbon or Habsburg—over the future successor to Spanish king Charles II, who had no children yet. Its North American theater, taking place simultaneously, was King William's War. Canadian and New England colonists fought on behalf of the French and British sides, each with different Native American allies. Both sides had military successes. The 1697 Peace of Rijswijk treaties which ended the war in Europe and North America left the Spanish succession dispute and the North American territorial disputes unsolved.[33][34][35]

Salem witch trials

[edit]The Salem witch trials were a widely controversial event in Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693. It started in spring 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts, when three girls who claimed to be possessed by the devil accused several local women of witchcraft. Mass hysteria over alleged witchcraft spread throughout the colony. As witchcraft was illegal, a special court convened in Salem to hear the legal cases against alleged witches. 150 people were accused, and 27 of them died in relation to the trials, most of them sentenced to death by hanging.[36][37]

18th century

[edit]Queen Anne's War

[edit]The War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1714 was a worldwide conflict that centered around the successor to Charles II of Spain, who died in 1700 with no children.[38][39] Philip V, grandson of French king Louis XIV, ascended to the Spanish throne, provoking their rivals, the English and Dutch.[38] The war's North American theater was Queen Anne's War from 1702 to 1713, as England (later Britain) and France fought for territory on the continent. English settlements—on the exposed frontier between British America and Canada, as well as around Charleston, South Carolina—were raided by the French and their Native American allies, so the Crown gave the colonists military aid. In the 1710 Siege of Port Royal, Britain conquered the Acadia region of New France. Acadia was made the British province of Nova Scotia. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France ceded Newfoundland and the Hudson Bay region to Britain.[38][40]

Yamasee War

[edit]The Yamasee War from 1715 to 1716 was between the British in southeastern South Carolina, and the Yamasee Native Americans with allies of other native tribes. The Yamasee resented the colonists for "settlers’ encroachment upon their land [and] unresolved grievances arising from the fur trade". The war started on April 15, 1715, when 90 white people—traders and their families—were killed by a group of Yamasee. Except for the Cherokee and Muscogee, all the nearby native tribes aided Yamasee raids of plantations and trading posts. New Englanders gave the South Carolinians troops and military supplies, weakening the native war effort. Some of the natives escaped to Florida, joining the Seminole people.[41][42]

War of Jenkins' Ear

[edit]In the 1730s, Britain and Spain tried to find a diplomatic solution to their centuries-long dispute over colonial Georgia and the surrounding lands. These negotiations failed, only leading to more animosity between them.[43] The two empires fought in the War of Jenkins' Ear from 1739 to 1748, which was subsumed into the War of the Austrian Succession from 1740 to 1748. In 1738, as the British public was spiteful towards Spain for their attacks on British ships, British Captain Robert Jenkins appeared before the House of Commons and showed them an amputated ear he alleged was cut off in 1731 by Spanish coast guards in the West Indies. Members of Parliament who were in opposition to British prime minister Robert Walpole seized on the political popularity of declaring war on Spain.[44] In the following years, British General James Oglethorpe captured many Spanish forts in Florida, British colonists in Georgia allied with the Native Americans to defend the colony from the Spanish, and the British kept their control over the region.[43]

French and Indian War

[edit]The French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763 was the North American theater of the Seven Years War, a worldwide conflict between Britain and France (despite the French and Indian War starting in 1754, the Seven Years War is commonly dated as 1756 to 1763). At the start, both countries had vast and conflicting territorial claims in North America. It started as a dispute over claims to the upper Ohio River valley. Britain wanted Pennsylvanians and Virginians to be able to settle and trade there; the area was already filled with English settlers, but the Native Americans there had alliances and trade with the French.[45][46]

In May 1754, British colonist George Washington assumed control of the Virginian militia, and garrisoned them at Fort Necessity in Pennsylvania, 60 kilometers (40 miles) north of Fort Duquesne, occupied by the French. On May 28, the British attacked a French scouting party, killing its commander Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. On June 3, the French attacked the British garrison at the Battle of Fort Necessity. Outnumbered, Washington surrendered the fort to the French, who burned it. He retreated with his militia back to Virginia. Virginia's government asked British king George II for aid; he was apprehensive, but ultimately sent a ground force under General Edward Braddock to help overthrow Fort Duquesne, and a naval force under Admiral Edward Braddock to patrol the Gulf of St. Lawrence and stop France from reinforcing Canadian troops.[45][46]

From June 19 to July 11, 1754, the Albany Congress was held in Albany, New York. It was a conference for delegates from seven of the thirteen colonies—Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island—to plan a combined defensive alliance against the French, and to gain the Iroquois Confederacy's loyalty against the French. Representatives of the Iroquois nations withdrew from the negotiations after some time. The colonial delegates debated how to regulate British—Native American affairs and the westward immigration of British colonists. Pennsylvania delegate Benjamin Franklin proposed the Albany Plan of Union, a "loose confederation" of the colonies, headed by a president general that could levy certain taxes, to be paid to a central treasury. The delegates voted for the plan, but it was disallowed by the Crown, who wanted to maintain their regional authority and sovereignty. However, the conference's idea of unifying the thirteen colonies under a loose confederation carried in regional politics.[47][48]

The British formally declared war in 1756. The first great British victory was at the Siege of Louisbourg, at the eastern end of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in July 1758. In July, the British won the Battle of Fort Frontenac on the western end. In November, the British captured Fort Duquesne and replaced it with Fort Pitt. The British closed in on the French in Quebec, and defeated them at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in September 1759. The French lost their remaining foothold in Canada, Montreal, during the Montreal campaign of September 1760. Spain joined the war as an ally of France, and the British began attacking Spanish and French territories in other parts of the world.[45][46]

Anglo-Cherokee War

[edit]The Anglo-Cherokee War of 1758 to 1761 was a small part of the French and Indian War, located in the southernmost thirteen colonies. Before the war, the Cherokee—about 7,700 to 9,000 in population—were allied with Britain against France, even though they [the Cherokee] resented parts of British rule. Some Cherokee mercenaries fought the French on the Virginia frontier. In late 1758, there was an incident where some Virginian colonists attacked Cherokee warriors returning from a battle with France. This was the final straw for the Cherokee in their opinion of the British. They rebelled, first in North Carolina, and spreading southwards. The war ended with a peace treaty between the British and Cherokee on September 23, 1761. The Cherokees were then ruled by a pro-English Cherokee man named Attakullakulla; lines were drawn as boundaries between the southern colonies and Cherokee lands; and Frenchmen in Cherokee lands were expelled. The Cherokee ended the war with a population of about 6,900.[49]

Tacky's Revolt

[edit]In 1760 and 1761, in Tacky's Revolt, African slaves in the British colony of Jamaica rebelled against their colonial slave-owners. Historian Vincent Brown writes: "[Tacky's Revolt] was part of four wars at once: it was an extension of wars on the African continent; it was a race war between black slaves and white slave holders; it was a struggle among black people over the terms of communal belonging, effective control of local territory, and establishment of their own political legacies; and it was, most immediately, one of the hardest-fought battles [of the] Seven Years’ War."[50] The Caribbean's control by the British was key to winning the Seven Year's War, so in response to the uprising, they "brought the full resources of transatlantic empire to bear against the rebels", bringing a local conflict into the global war before ending it quickly.[51]

The Treaty of Paris (1763) and Pontiac's War

[edit]The British ultimately won the Seven Years War. Britain, France, and Spain formally ended the Seven Years War with the Treaty of Paris of 1763. Canada and Spain gave Britain Canada and Florida, respectively. France gave Louisiana to Spain, but kept its sugar-producing islands in the West Indies. Britain left the war with twice as much national debt, as their war effort was paid with large amounts of borrowed money from British and Dutch bankers.[46][52]

When the British inherited the French lands of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, they also received France and Spain's diplomatic situations with the Native Americans of Spain, Canada, and the Great Lakes region. The British had to decide if the natives would be subject to the British Empire or allowed some autonomy. Their decision is represented by the words of Jeffrey Amherst, the governor general in North America, who said the Native Americans are "the Vilest Race of Beings that Ever Infested the Earth", and "the only true method of treating those [people] is to keep them in a proper subjection.” The British severed ties with the native nations. British settlers increased in native lands, while British troops were stationed in the Great Lakes region and restrictions were put on trade between the colonists and natives.[53]

The Native Americans, predicting "the English have a mind to cut them off the face of the earth", rebelled in Pontiac's War from 1763 to 1765. Fourteen native tribes—who spoke Algonquian, Iroquoian, Muskogean, or Siouan languages—started fighting the British in the Great Lakes region. Intense fighting went on for two years, and ended in a stalemate. Ultimately, the Crown was forced to give the natives more autonomy; this increased colonial resentment against the monarchy, fueling revolutionary sentiment.[53]

American Revolution

[edit]In March 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, taxing many transactions in the thirteen colonies to pay Britain's debt from the Seven Years War. The Crown also felt the colonies should repay them for saving the colonists from attacks by the natives. Previously, each colony decided how taxes were levied and collected, and the act was unpopular. The new taxes were never collected, as Americans rioted over them, and Benjamin Franklin influenced Parliament to rescind it.[54] The Townshend Acts of June and July 1767 were the Crown asserting its authority over the colonies: colonist citizens and officials were illicitly smuggling British goods, so Parliament made customs commissioners to oversee the trade, stop smuggling, and tax the goods. The colonists stopped buying the goods and harassed the commissioners. The Crown then had troops occupy Boston.[54]

On March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston, amidst tensions between British soldiers and Bostonians, an argument between a soldier and a wigmaker led to 200 colonists surrounding seven soldiers and throwing objects at them. This prompted the Boston Massacre, when the soldiers fired at five Bostonians; three died, which was useful for anti-monarchist colonists.[54] Henry Pelham and Paul Revere's engraving of the massacre that depicted the soldiers as the aggressors, was distributed throughout the colonies, effectively stoking anti-monarchist anger.[54][55]

The Crown withdrew its soldiers from Boston, and rescinded the Townshend Acts. However, in 1773, they enacted the Tea Act to help the struggling British East India Company. The company could now sell tea in the colonies at a cheaper price than local tea merchants, who imported from Dutch traders—hurting local merchants' business. Colonists were again angered, wanting to trade with which ever country they wanted and not be forced to buy English tea. The Sons of Liberty, anti-monarchist radicals, responded with the Boston Tea Party, disguising themselves as Mohawk to board British ships in the Boston Harbor, and dumping 92,000 pounds of tea into the water. Parliament, many members of which had large shares in the British East India Company, wanted to punish the colonists.[54]

The Crown, wanting to punish the Massachusetts colonists, passed laws from March to June 1774 which some colonists labeled the "Intolerable Acts". The colony's elected council was replaced with one ran by the Crown, and British military governor General Thomas Gage was given vast powers. Town meetings without official approval were banned, and the Boston Harbor was closed until the losses from the Tea Party were paid off. The Quartering Act allowed British soldiers—until then, camping in the countryside—to garrison in unoccupied buildings in town, and the colonists had to pay for the soldiers' housing and food.[54] The First Continental Congress of colonists met in Philadelphia in September 1774, to formally denounce "taxation without representation" and the forced maintenance of the garrisons.[56]

American Revolutionary War

[edit]At the start of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, the British Empire included 23 colonies and territories on the North American continent.[57] On April 18, 1775, British troops in Boston began marching to Concord, Massachusetts, to seize an arms cache owned by rebel militiamen. The rebels were warned of this, and they intercepted the Crown's soldiers at the Battles of Lexington and Concord the next day, starting the war. British troops and their Loyalist colonist allies fought against Patriot rebel colonists. The Second Continental Congress voted to form the Continental Army, headed by George Washington, to lead the Patriot war effort. The Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston on June 17 ended in a British victory, but motivated Patriots.[56]

By June 1776, a majority of colonists in the thirteen colonists were in favor of seceding from the Crown. On July 4, the Continental Congress voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence, written mainly by Thomas Jefferson, declared the colonies as a country of thirteen unified states independent from Britain, named the "United States of America". In 1777, the British tried to hurt the American war effort by putting themselves between New England and the colonies to the south. In the Battles of Saratoga at Saratoga, New York in September and October, the Americans defeated the British.[56] Also that year, the U.S. adopted the Articles of Confederation, a federal constitution that was enforced from 1781 to 1789.[58]

The British loss at Saratoga influenced France, still Britain's rival, to openly join the war on the American side, after secretly aiding them for a year. The French openly declared war on Britain in June 1778. The Spanish and Dutch, also enemies with Britain, began helping the Americans.[56][59] In autumn 1871, British forces led by Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis were forced by the Americans into Yorktown, Virginia, near Chesapeake Bay. On October 19, 1781, the British were defeated by George Washington's forces at the Battle of Yorktown. The remaining British troops were relegated to the Carolinas and Georgia; they did not engage in "decisive action" with the Americans, and in late 1872, the Crown pulled them out of the colonies, effectively ending conflict.[56][60]

The Treaty of Paris was deliberated in 1783 between American statesmen Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay; and representatives of British king George III. The two countries formally ended the war, and Britain recognized the U.S. government as legitimate. Britain ceded the territory of the former thirteen colonies, as well as most British territory to the east of the Mississippi River and the vast Northwest Territory, which spanned the modern states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and partially, Wisconsin. Britain made peace treaties with France, the Dutch Republic, and Spain later in 1783.[61]

After the Treaty of Paris (1783)

[edit]After 1783, Britain ceded East and West Florida to the Kingdom of Spain, which in turn ceded them to the United States in 1821. The Atlantic archipelago of the Bahamas had been administratively grouped with the North American continent, but with the loss of the Floridas was grouped with the British colonies of the Caribbean as the British West Indies.

Most of the remaining colonies to the north (including the continental colonies and the archipelago of Bermuda, the nearest landfall from which was North Carolina, but the nearest other British territory from which became Nova Scotia) formed the Dominion of Canada in 1867, with the colony of Newfoundland (which had become the Dominion of Newfoundland in 1907, leaving Bermuda as the only remaining British colony in British North America, before reverting to a colony in 1934) joining the independent Commonwealth realm of Canada in 1949, and Bermuda, elevated (by the independence of the thirteen colonies that became the United States) to the role of an Imperial fortress and the most important British naval and military base in the Western Hemisphere (due to its location, 1,236 km (768 mi) south of Nova Scotia, and 1,538 km (956 mi) north of the British Virgin Islands, and handily placed for naval and amphibious operations against its nearest neighbour, the nascent United States, during the 19th century), remains as a British Overseas Territory today.

North American colonies in 1775

[edit]The Thirteen Colonies that became the original states of the United States were:

Colonies and territories that became part of British North America (and from 1867 the Dominion of Canada):

- Province of Quebec northeast of the Great Lakes (including Labrador until 1791)

- Nova Scotia (including New Brunswick until 1784)

- Island of St. John

- Rupert's Land

- North-Western Territory

- British Arctic Territories

Colonies that became part of British North America (but which would be left out of the 1867 Confederation of Canada):

Colonies and territories that were ceded to Spain or the United States in 1783:

- Province of East Florida (Spanish 1783–1823, U.S. after 1823)

- Province of West Florida (Spanish 1783–1823, U.S. after 1823)

- Indian Reserve (U.S. after 1783)

- Province of Quebec southwest of the Great Lakes (U.S. after 1783)

Colonies in the Caribbean, Mid-Atlantic, and South America in 1783

[edit]- Divisions of the British Leeward Islands

- Saint Christopher (de facto capital)

- Antigua

- Barbuda

- British Virgin Islands

- Montserrat

- Nevis

- Anguilla

-

- Island of Jamaica

- Settlement of Belize in British Honduras

- Mosquito Coast

- Bay Islands

- Cayman Islands

- Old Providence Island Colony

- Other possessions in the British Windward Islands

- Island of Barbados

- Island of Grenada

- Island of St. Vincent

- Island of Tobago (detached from Grenada in 1768)

- Island of Dominica (detached from Grenada in 1770)

Imperial administration after 1783

[edit]

The Home Office was formed on 27 March 1782, responsible for the administration of all British territory, within and without the British Isles, taking over the administration of the British colonies, including those of British North America, from the Board of Trade and the first Colonial Office. Dissatisfaction with the then Home Secretary (who oversaw the Home Office), William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, during two decades of war with the French Republic led to colonial business being transferred to the War Office in 1801, which became the War and Colonial Office, with the Secretary of State for War was renamed the Secretary of State for War and Colonies. From 1824, the British Empire was divided by the War and Colonial Office into four administrative departments, including NORTH AMERICA, the WEST INDIES, MEDITERRANEAN AND AFRICA, and EASTERN COLONIES, of which North America included:[64]

North America

The Colonial Office and War Office, and the Secretary of State for the Colonies and the Secretary of State for War, were separated in 1854.[65][66] The War Office, from then until the 1867 confederation of the Dominion of Canada, split the military administration of the British colonial and foreign stations into nine districts: North America And North Atlantic; West Indies; Mediterranean; West Coast Of Africa And South Atlantic; South Africa; Egypt And The Sudan; INDIAN OCEAN; Australia; and China. North America And North Atlantic included the following stations (or garrisons):[67]

North America and North Atlantic

- New Westminster (British Columbia)

- Newfoundland

- Quebec

- Halifax

- Kingston, Canada West

- Bermuda

The Colonial Office, by 1862, oversaw eight Colonies in British North America,[68] including:

North American Colonies, 1862

- Canada

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Prince Edward Island

- Newfoundland

- Bermuda

- Vancouver Island

- British Colombia

By 1867, administration of the South Atlantic Ocean archipelago of the Falkland Islands, which had been colonised in 1833, had been added to the remit of the North American Department of the Colonial Office.[69]

North American Department of the Colonial Office, 1867

- Canada

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Prince Edward Island

- Newfoundland

- Bermuda

- Vancouver Island

- British Colombia

- Falkland Islands

Following the 1867 confederation, Bermuda and Newfoundland remained as the only British colonies in North America (although the Falkland Islands also continued to be administered by the North American Department of the Colonial Office).[70] The reduction of the territory administered by the British Government would result in re-organisation of the Colonial Office. In 1901, the departments of the Colonial Office included: North American and Australasian; West Indian; Eastern; South African; and West African (two departments).[71] In 1907, the Colony of Newfoundland became the Dominion of Newfoundland, leaving the Imperial fortress of Bermuda as the sole remaining British North American colony. By 1908, the Colonial Office included only two departments (one overseeing dominion and protectorate business, the other colonial): Dominions Department (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Newfoundland, Transvaal, Orange River Colony, Australian States, Fiji, Western Pacific, Basutoland, Bechuanaland Protectorate, Swaziland, Rhodesia); Crown Colonies Department. The Crown Colonies Department was made up of four territorial divisions: Eastern Division; West Indian Division; East African and Mediterranean Division; and the West African Division. Of these, the West Indian Division now included all of the remaining British colonies in the Western Hemisphere, from Bermuda to the Falkland Islands.[72]

See also

[edit]- Evolution of the British Empire

- British colonization of the Americas

- Colonial history of the United States

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

- British colonization of Australia

- British colonization of New Zealand

- British North America Acts

- British overseas territories

Notes

[edit]- ^ Formerly called English America before the Act of Union in 1707.

References

[edit]- ^ "Iroquois Confederacy | Definition, Significance, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (31 March 2016). "View From Space Hints at a New Viking Site in North America". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus | Biography, Nationality, Voyages, Ships, Route, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2 December 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Santo Domingo | History, Culture, Map, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 9 December 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b "7 Failed North American Colonies". HISTORY. 6 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ a b "New France | Definition, History, & Map | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b c "Lost Colony | Roanoke Island, Virginia, 1587 | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 30 October 2024. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ a b "What Happened to the 'Lost Colony' of Roanoke?". HISTORY. 20 June 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Jamestown Colony | History, Foundation, Settlement, Map, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 22 September 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b Yorktown, Mailing Address: P. O. Box 210; Us, VA 23690 Phone: 757 898-2410 Contact. "A Short History of Jamestown - Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Jamestown Colony ‑ Facts, Founding, Pocahontas". HISTORY. 27 June 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. "Popham Colony". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "The Lost Colony of Popham". HISTORY. 1 June 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. "Anglo-Powhatan Wars". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Powhatan War | Native Americans, Jamestown, Virginia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Bermuda - British Colony, Shipwrecks, Tourism | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 17 November 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Plymouth Colony ‑ Location, Pilgrims & Thanksgiving". HISTORY. 20 August 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Plymouth | Rock, Massachusetts, Colony, Map, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 20 September 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Transatlantic slave trade | History & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 September 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d "African Americans | History, Facts, & Culture | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 4 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b Yan, Holly (11 February 2019). "Virginia's governor called slaves 'indentured servants.' Here's a fact check". CNN. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "The settlement of Maryland | March 25, 1634". HISTORY. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Maryland - Colonial, Chesapeake, Plantations | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b Mark, Joshua J. "Pequot War". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Pequot War | History, Facts, & Significance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ Foulds, Nancy Brown. "Colonial Office". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Davidson, Justin (13 March 2024). "The Streets of Pre–New York". Curbed. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "Dutch West India Company | New Netherland, Colonization, Slavery | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "New Amsterdam becomes New York | September 8, 1664". HISTORY. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "King Philip's War | Cause, Summary, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 19 September 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "King Philip's War ‑ Definition, Cause & Significance". HISTORY. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Metacom | Biography, War, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2 December 2024. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ "King William's War | Native American, French, British | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "War of the Grand Alliance | European History, Causes & Consequences | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "American colonies - French Rivalry, Colonial Wars, Imperial Conflict | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 16 November 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Salem Witch Trials ‑ Events, Facts & Victims". HISTORY. 19 September 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Blumberg, Jess. "A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "War of the Spanish Succession". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Charles II | Restoration, Habsburg Dynasty & Reunification | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2 November 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Queen Anne's War | Native American, French, British | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Yamasee War | Native American, Colonial, Conflict | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Yamassee War". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b "War of Jenkins' Ear". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "War of Jenkins' Ear | Spanish-British, Caribbean, 1739-1748 | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c "French and Indian War | Definition, History, Dates, Summary, Causes, Combatants, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 24 October 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d "French and Indian War ‑ Seven Years War". HISTORY. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Albany Congress | Definition & Significance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Cherokee War (1759-1761)". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Tacky's Revolt". www.amrevmuseum.org. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ Gardner, John S. (29 February 2020). "Tacky's Revolt review: Britain, Jamaica, slavery and an early fight for freedom". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Treaty of Paris | End of French & Indian War, Peace, Colonies | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Pontiac's Rebellion | George Washington's Mount Vernon". www.mountvernon.org. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "7 Events That Enraged Colonists and Led to the American Revolution". HISTORY. 6 August 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "How Paul Revere's Engraving of the Boston Massacre Rallied the Patriot Cause". HISTORY. 20 June 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Revolutionary War ‑ Timeline, Facts & Battles". HISTORY. 24 June 2024. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "American Revolution | Causes, Battles, Aftermath, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 19 October 2024. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Articles of Confederation (1777)". National Archives. 9 April 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Battle of Saratoga ‑ Definition, Significance & Date". HISTORY. 13 June 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Battle of Yorktown ‑ Definition, Who Won & Importance". HISTORY. 21 June 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "Treaty of Paris ‑ Definition, Date & Terms". HISTORY. 21 June 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Rhode Island Royal Charter of 1663". sos.ri.gov. Secretary of State of Rhode Island. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ "Charles II Granted Rhode Island New Charter". christianity.com. 8 July 1663. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Young, Douglas MacMurray (1961). The Colonial Office in The Early Nineteenth Century. London: Published for the Royal Commonwealth Society by Longmans. p. 55.

- ^ Maton, 1995, article

- ^ Maton, 1998, article

- ^ METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS AT THE FOREIGN AND COLONIAL STATIONS OF THE ROYAL ENGINEERS AND THE ARMY MEDICAL DEPARTMENT 1852—1886. London: Published by the authority of the Meteorological Council. PRINTED FOR HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE BY EYRE AND SPOTTISWOODE, East Harding Street, Fleet Street, London E.C. 1890.

- ^ "COLONIAL GOVERNORS AND BISHOPS". The Wiltshire County Mirror. Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. 1 October 1862. p. 7.

The annual return has been issued by the Colonial-office, containing the list of Governors and Bishops. Our North American colonies are eight in number, - Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, Bermuda, Vancouver Island, and British Colombia;

- ^ BIRCH, ARTHUR N.; ROBINSON, WILLIAM (1867). THE COLONIAL OFFICE LIST FOR 1867: COMPRISING Historical and Statistical Information RESPECTING THE COLONIAL DEPENDENCIES OF GREAT BRITAIN, AN ACCOUNT OF THE SERVICES OF THE PRINCIPAL OFFICERS OF THE SEVERAL COLONIAL GOVERNMENTS. WITH MAP. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL RECORDS, &c., &c., WITH PERMISSION OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES. BY ARTHUR N. BIRCH, AND WILLIAM ROBINSON, OF THE COLONIAL OFFICE. LONDON: HARRISON. BOOKSELLER TO HER MAJESTY AND H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES. Printed by HARRISON AND SONS. p. 8.

- ^ Fairfield, Edward (1878). THE COLONIAL OFFICE LIST FOR 1878: COMPRISING Historical and Statistical Information RESPECTING THE COLONIAL DEPENDENCIES OF GREAT BRITAIN, AN ACCOUNT OF THE SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS IN THE COLONIAL SERVICE; A TRANSCRIPT OF THE COLONIAL REGULATIONS, AND OTHER INFORMATION. WITH MAPS. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL RECORDS* BY PERMISSION OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES, BY EDWARD FAIRFIELD, OF THE COLONIAL OFFICE. LONDON: HARRISON AND SONS, Printers in Ordinary to Her Majesty. Page 17, PART II. — COLONIES .-- COLONIAL GOVERNORS. Colonies. North American.

CANADA: PROVINCES OF CANADA-Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, North-west Territories, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island; NEWFOUNDLAND; BERMUDA; FALKLAND ISLANDS

- ^ Mercer, W. H.; Collins, A. E. (1901). THE COLONIAL OFFICE LIST FOR 1901: COMPRISING Historical and Statistical Information RESPECTING THE COLONIAL DEPENDENCIES OF GREAT BRITAIN, AN ACCOUNT OF THE SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS IN THE COLONIAL SERVICE; A TRANSCRIPT OF THE COLONIAL REGULATIONS, AND OTHER INFORMATION. WITH MAPS. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL RECORDS* BY PERMISSION OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES, BY W. H. MERCER, One of the Crown Agents for the Colonies, and A. E. COLLINS, OF THE COLONIAL 0FFICE. LONDON: HARRISON AND SONS, Printers in Ordinary to Her late Majesty. p. xiii.

- ^ Mercer, W. H.; Collins, A. E. (1908). THE COLONIAL OFFICE LIST FOR 1901: COMPRISING Historical Statistical Information RESPECTING THE COLONIAL DEPENDENCIES OF GREAT BRITAIN, AN ACCOUNT OF THE SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS IN THE COLONIAL SERVICE; A TRANSCRIPT OF THE COLONIAL REGULATIONS, AND OTHER INFORMATION. WITH MAPS. COMPILED FROM OFFICIAL RECORDS* BY PERMISSION OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES, BY W. H. MERCER, One of the Crown Agents for the Colonies, and A. E. COLLINS, OF THE COLONIAL 0FFICE. LONDON: Waterlow and Sons Limited. p. xiii.

- 1607 establishments in the British Empire

- 1783 disestablishments in North America

- 1783 disestablishments in the British Empire

- British colonization of the Americas

- British North America

- Colonial United States (British)

- Colonization history of the United States

- English-speaking countries and territories

- History of the Caribbean

- States and territories established in 1607