The Bridge at No Gun Ri

Book cover | |

| Author | Charles J. Hanley, Sang-hun Choe, Martha Mendoza |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Korean War massacre |

| Genre | Narrative history |

| Publisher | Henry Holt and Company |

Publication date | September 6, 2001 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 313 |

| ISBN | 0-8050-6658-6 |

The Bridge at No Gun Ri is a non-fiction book about the killing of South Korean civilians by the U.S. military in July 1950, early in the Korean War. Published in 2001, it was written by Charles J. Hanley, Sang-hun Choe and Martha Mendoza, with researcher Randy Herschaft, the Associated Press (AP) journalists who wrote about the mass refugee killing in news reports that won the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism and 10 other major national and international journalism awards. The book looks in depth at the lives of both the villager victims and the young American soldiers who killed them, and analyzes various U.S. military policies including use of deadly force in dealing with the refugee crisis during the early days of the war.

Synopsis

[edit]The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War is written in chronological narrative style and is organized in three parts, "The Road to No Gun Ri," "The Bridge at No Gun Ri," and "The Road from No Gun Ri." It opens with two chapters that alternately introduce the readers to the young Army enlistees of the 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, mostly from poor backgrounds, many of them school dropouts, on occupation duty in post-World War II Japan, where they have been insufficiently trained and are unprepared for the sudden outbreak of war in nearby Korea; and then to the South Korean villager families and the age-old rhythms of their rural lives, to be exploded in late June 1950 by a Korean civil war borne of the new U.S.-Soviet rivalry, the Cold War.

The next two chapters describe the deployment of U.S. military units to face the onrushing North Korean invaders, the growing nervousness of U.S. commanders who issue orders to fire on South Korean refugee columns out of fear of enemy infiltrators, and the disarray of the weakly led 7th Cavalrymen as they reach the warfront; and then tell of the villagers' plight as they first seek shelter from the war by gathering in a remote area of their valley, and then are forced by retreating U.S. troops to head south toward U.S. lines.

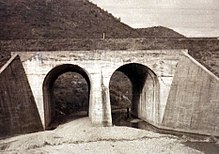

The 26-page middle section is an account of the three days of carnage that began with U.S. warplanes attacking the column of hundreds of refugees, after which survivors were forced into an underpass and machine-gunned until few were left alive among piles of bodies. Survivors estimated 400 were killed, mostly women and children. (The South Korean government-funded No Gun Ri Peace Foundation estimated in 2011 that 250-300 were killed.) Some Seventh Cavalry veterans recalled orders coming down to stop all refugees from crossing U.S. lines and to "eliminate" the No Gun Ri group. This and earlier chapters describe declassified military documents showing such orders spreading across the warfront.

The final section of four chapters follows the stories of lives shattered when they intersected at No Gun Ri, both of Korean villagers fighting to survive in the chaos of war, and of young U.S. soldiers fighting in the seesaw battles of 1950-51. In the postwar decades, the psychic toll of what the Koreans suffered and what the Americans did and witnessed weighs heavily on both, leaving them deeply depressed, sometimes suicidal, often haunted by visions and ghosts. One, Chung Eun-yong, a former policeman whose two children were killed at No Gun Ri, makes it his life mission to find the truth of who was responsible for the massacre. The section ends when an Associated Press reporter telephones Chung at the beginning of a lengthy journalistic investigation.

The book has two epilogues. The first describes the AP investigative work that found the U.S. veterans who corroborated the Korean survivors' story and the declassified documents that further supported it, and the bibliographic, archival and interview sources for the book. (The AP team's editor, Bob Port, later wrote about the reporters' yearlong struggle to publish their explosive report in the face of resistance by AP executives.)[1] The second epilogue details the serious irregularities in the U.S. Army report[2] on the No Gun Ri investigation prompted by the AP disclosures. (Co-author Hanley later published a more extensive analysis of what the Korean survivors described as a "whitewash.")[3]

Reviews

[edit]The Bridge at No Gun Ri is "one of the best books ever to appear on Americans in foreign wars," wrote historian Bruce Cumings, an American scholar of East Asia and the Korean War.[4] On the cover, Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Sydney Schanberg said the book is "in a class to stand with such work as Hersey's Hiroshima and Keneally's Schindler's List … powerful history." The New Yorker magazine said it "raises questions about military preparedness and civilian involvement that are as relevant today as they were half a century ago. ... The book is a sobering testament to the ravages of combat."[5] The Far Eastern Economic Review declared it "great journalism and scholarship and also a great read."[6] In a starred review, Kirkus Reviews said, "In crisp and forceful prose, the authors explain how No Gun Ri, like My Lai, was only the tip of the civilian-killing, scorched-earth iceberg. ... A wrenching story."[7] Library Journal said it "tells a grim but true story. The authors have done their research and tell an excellent tale -- one that the U.S. Army tried to forget."[8] The Economist also cited its "faithful" and "meticulous" research.[9] Publishers Weekly described the book as "advocacy reportage" that "eschewed critical analysis by concentrating on the victims on both sides of the rifles."[10]

Writing in The Journal of Military Ethics, Lieutenant Commander Greg Hannah of Canada's Royal Military College said of The Bridge at No Gun Ri, "Interviews with survivors and soldiers provide vivid and compelling narrative details for this book. ... Compelling documentary evidence is offered that makes it clear that official policy authorized killing of refugees and that written orders to do so were issued."[11]

Publication

[edit]Several months after the September 29, 1999, publication of the AP's initial news report on No Gun Ri, the journalists signed a contract with Henry Holt and Company to write a book, working with Holt editor Liz Stein. The Bridge at No Gun Ri led Holt's catalog list for the fall 2001 season. But its publication date of September 6, 2001, came just five days before the 9/11 terror attacks, which jolted the publishing industry, caused the cancellation of the authors' national promotional tour, and dried up the book's promising sales.[12]

The 313-page book, later released in paperback, features 35 photographs, two maps, two charts explaining the U.S. Army command structure in Korea and the villagers' family relationships, and reproductions of three key documents among the many demonstrating the policy of shooting refugees. The authors conducted some 500 interviews, chiefly with 24 ex-soldier witnesses and 36 Korean survivors. The AP journalism had drawn criticism in 2000 when it emerged that one of nine ex-soldiers quoted in the original story was not at No Gun Ri, as purported, but was passing on second-hand information. That source doesn't appear in the book's account of the massacre.[13]

Translation, adaptations

[edit]In 2003, a Korean-language translation of The Bridge at No Gun Ri was published in Seoul.[14] The Seoul movie studio Myung Films partly based its 2009 feature film about the massacre, A Little Pond, on The Bridge at No Gun Ri.[15] Three major television documentaries, by the British Broadcasting Corporation,[16] Germany's national ARD television[17] and South Korea's Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation,[18] drew heavily on The Bridge at No Gun Ri.

References

[edit]- ^ Port, J. Robert (2002). "The Story No One Wanted to Hear". In Kristina Borjesson (ed.). Into the Buzzsaw: Leading Journalists Expose the Myth of a Free Press. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. pp. 201–213. ISBN 978-1-57392-972-1.

- ^ Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Army. No Gun Ri Review. Washington, D.C. January 2001

- ^ Hanley, Charles J. (2012). "No Gun Ri: Official Narrative and Inconvenient Truths". In Jae-Jung Suh (ed.). Truth and Reconciliation in South Korea: Between the Present and Future of the Korean Wars. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 68–94. ISBN 978-0-415-62241-7.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (December 2001). "Occurrence at Nogun-ri Bridge". Critical Asian Studies. 33 (4): 506–526. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ "The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War". The New Yorker. October 29, 2001. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ Kattoulas, Velisarios (January 24, 2002). "The Bridge at No Gun Ri : A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War". Far Eastern Economic Review: 62.

- ^ "The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War". Kirkus Reviews. July 1, 2001. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- ^ Ellis, Mark (August 2001). "The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War". Library Journal.

- ^ "The first casualty: War and its victims". The Economist. August 23, 2001. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Publishers Weekly. Review: THE BRIDGE OF NO GUN RI: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War

- ^ Hannah, Lieutenant Commander Gregg (January 2004). "The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War". Journal of Military Ethics. 3 (1): 75–78. doi:10.1080/15027570310004942. S2CID 216117183.

- ^ "After the attack, industry moves forward". Publishers Weekly. 248 (39): 9–10. September 24, 2001.

- ^ "Ex-GI acknowledges records show he couldn't have witnessed killings". The Associated Press. 2000-05-25.

- ^ Choe, Sang-hun; Hanley, Charles; Mendoza, Martha (2003). 노근리 다리 (The Bridge at No Gun Ri). Seoul, South Korea: Ingle Publishing Company. ISBN 978-89-89757-03-0.

- ^ "Story of Nogeun-ri Massacre To Be Made Into Movie". Yonhap News Agency. July 29, 2003.

- ^ British Broadcasting Corp., October Films. "Kill 'em All," Timewatch, February 1, 2002

- ^ ARD Television, Germany. "The Massacre of No Gun Ri," March 19, 2007, retrieved January 28, 2012

- ^ Munwha Broadcasting Corp., South Korea, "No Gun Ri Still Lives On: The Truth Behind That Day," September 2009.

External links

[edit]• Henry Holt and Company website for ‘’The Bridge at No Gun Ri”

• C-SPAN book discussion, The Bridge at No Gun Ri, Berkeley, CA, September 10, 2001.