Brian Herbert Medlin

Emeritus Professor Brian Herbert Medlin | |

|---|---|

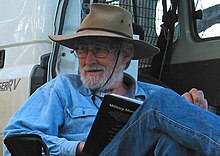

Brian Medlin picnicking at MacKenzie Creek Victoria. A self-portrait using his new digital camera. By permission Estate Brian Medlin. | |

| Born | 1927 Orroroo, South Australia, Australia |

| Died | 2004 (aged 76–77) |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Relatives | Harry Medlin (brother) |

Philosophy career | |

| Education | University of Adelaide, University of Oxford |

| Alma mater | University of Adelaide |

| Institutions | Flinders University of South Australia |

| Language | English |

Main interests | Philosophy of mind, political philosophy, "applying philosophical methods to current problems and social issues" |

Brian Herbert Medlin (1927–2004) was Foundation[1] Professor of Philosophy at Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia, from 1967 to 1988.[2] He pioneered radical philosophy in Australian universities[3] and played an active role in the campaign against the Vietnam War.[2]

Early life

[edit]Medlin was born in 1927 in Orroroo, South Australia. He was the younger brother of Harry Medlin, who became the Deputy Chancellor of the University of Adelaide.[4] Medlin attended Richmond Primary School and Adelaide Technical High School. While at high school, Medlin was introduced to the philosophy of Bertrand Russell. He worked in the Northern Territory after graduating from secondary school, working in the pastoral industry in various capacities. He returned to Adelaide in the mid-1950s and while working as a teacher he studied English, Latin and Philosophy at the University of Adelaide, graduating in 1958 with first-class honours. During his university years he associated with writers such as John Bray, Charles Jury, Max Harris and Mary Martin. He received a scholarship to attend Oxford University, where he spent several years.[5] He met the British writer and philosopher Iris Murdoch in the early 1960s and on his return to Australia corresponded with her for several decades.[6] Their correspondence was a significant influence on Murdoch's depiction of Australia in her novels.[7] During his Oxford years, he spent a year teaching philosophy in Ghana.[5]

Academic career

[edit]On his return to Australia in 1964, Medlin initially worked as a Reader at the University of Queensland. His early interests included the identity theory of mind and the nature of egoism.[8] In 1967 he was appointed to the newly established Flinders University of South Australia as the Foundation Professor of Philosophy. In 1970, he adopted revolutionary socialism and with colleagues introduced new topics concerned with "applying philosophical methods to current problems and social issues".[9] He developed innovative courses in women's studies, and politics and art, and instituted a student-staff consultative committee.[5] He became known nationally as "an early leader in the ‘red shift’ in academic philosophy."[3] In 1971 he was described as "spearheading the revolution" in philosophy which polarised academics in Australia when he draped a red flag over the podium at the conference of the Australian Association of Philosophers.[10] He retired from Flinders in 1988, after a serious motorcycle accident in 1983 had long-term effects on his health. He was awarded the title of Emeritus Professor.[5] Medlin's influence is attested by obituaries published in the national daily Australian newspaper[2] and in the Australian Federal Senate.[5]

Activism

[edit]Medlin was strongly opposed to Australia's participation in the Vietnam War. He was chairman of the Campaign for Peace in Vietnam (CPV) in South Australia. Medlin played a leading role with other activists such as Lynn Arnold in the anti-war campaign. He was arrested during a Vietnam Moratorium Campaign (VMC) march in September 1970 and imprisoned for three weeks. During this time, his supporters kept a candlelit vigil outside Adelaide jail.[2] These experiences contributed to his influential course on politics and the arts taught at Flinders University, which prompted the formation of the well-known Australian progressive rock band Redgum.[2] Over many years Medlin was subject to covert surveillance by ASIO for his activism and radicalism. Redgum went on to produce a song that satired and criticised ASIO's surveillance of peace activists.[4]

Later career

[edit]After his retirement from Flinders University, Medlin moved to Victoria with his wife, Christine Vick, and spent some years regenerating a 10-acre property at Wimmera with native vegetation. He retained an interest in many subjects including natural history, literature, current affairs and photography.[5] He died in 2004.

Writings

[edit]In 1957, while still studying at Adelaide University, Medlin published an article titled "Ultimate principles and ethical egoism"[11] that continues to be seen as a significant contribution to debates about egoism. For example in 2007, Stephen R.C. Hicks wrote, in reference to this essay, "Brian Medlin was representative" of his generation in tending to scepticism and non-naturalism.[12] His 1963 article "The origin of motion"[13] is discussed in detail in N. Strobach's "The Moment of Change" (2013).[14] Medlin also wrote poetry, which was widely published in Australian periodicals through the 1950s and 1960s, and short fiction, often using the pseudonym Timothy Tregonning. Many unpublished works are in the Brian Medlin Collection[1] at Flinders University. A collection of his essays, stories and poems titled The Level-Headed Revolutionary was published by Wakefield Press in 2021.[15]

Bibliography

[edit]Archive

[edit]Brian Medlin Collection,[1] Special Collections, Flinders University Library, Bedford Park, South Australia.

Books

[edit]Human Nature Human Survival. Adelaide: Board of Research, Flinders University, 1992.

Never Mind about the Bourgeoisie: The Correspondence between Iris Murdoch and Brian Medlin 1976–1995. Edited by Gillian Dooley and Graham Nerlich. Newcastle on Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2014.

The Level-Headed Revolutionary: Essays, Stories and Poems by Brian Medlin. Edited by Gillian Dooley, Wallace McKitrick and Susan Petrilli. Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Brian Medlin Collection". Flinders University of South Australia. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Schumann, John (17 November 2004). "Democracy drove radical". The Australian.

- ^ a b Franklin, James (2003). Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia. Macleay Press. pp. 289–291, 307.

- ^ a b Kovac, Anna (2015). "ASIO's Surveillance of Brian Medlin". Flinders Journal of History and Politics. 31: 112–138 – via Proquest.

- ^ a b c d e f Lees, Meg (6 December 2004). "Medlin, Brian". Australian Senate Hansard.

- ^ Dooley, Gillian; Nerlich, Graham (2014). Never Mind about the Bourgeoisie. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1443855440.

- ^ Dooley, Gillian (December 2011). "You are my Australia: Brian Medlin's contribution to Iris Murdoch's concept of Australia in The Green Knight". Antipodes. 25 (2): 157–162 – via Proquest, Gale etc.

- ^ Oppy, Graham (2011). The Antipodean Philosopher. London, New York etc.: Lexington Books. p. 144. ISBN 9780739167939.

- ^ Hilliard, David (1991). Flinders University: the first 25 years 1966–1991. Adelaide: Flinders University. p. 57. ISBN 0725805013.

- ^ Williams, Graham (13 March 1971). "Under the red flag". Advertiser (Adelaide, S.A.).

- ^ Medlin, Brian (1957). "Ultimate principles and ethical egoism". Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 35 (2): 111–118. doi:10.1080/00048405785200121.

- ^ Hicks, Stephen R.C. (2007). "Tara Smith: Ayn Rand's Normative Ethics: The Virtuous Egoist". Philosophy in Review. 27 (5) – via Gale.

- ^ Medlin, Brian (1963). "The origin of motion". Mind. 72 (286): 155–175. doi:10.1093/mind/LXXII.286.155.

- ^ Strobach, Niko (2013). The moment of change: a systematic history in the philosophy of space and time. Springer. pp. 154–160. ISBN 9789401591270.

- ^ Medlin, Brian (2021). "The Level-headed Revolutionary: Essays, Stories and Poems". www.wakefieldpress.com.au. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- 1927 births

- 2004 deaths

- Analytic philosophers

- Anti–Vietnam War activists

- Academic staff of Flinders University

- Australian environmentalists

- Australian essayists

- Australian ethicists

- Australian humanists

- Australian male non-fiction writers

- Australian male poets

- Australian male short story writers

- Australian pacifists

- 20th-century Australian philosophers

- Australian photographers

- Australian socialists

- Environmental philosophers

- Environmental writers

- Epistemologists

- Metaphysicians

- Metaphysics writers

- Ontologists

- Philosophers of art

- Philosophers of culture

- Philosophers of education

- Philosophers of history

- Philosophers of literature

- Philosophers of mind

- Philosophers of social science

- Philosophers of war

- Australian philosophy academics

- Political controversies in Australia

- Australian political philosophers

- Redgum

- Social philosophers

- Sustainability advocates

- Theorists on Western civilization