Bossa nova

| Bossa nova | |

|---|---|

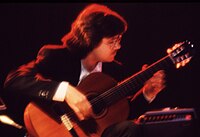

Vinicius de Moraes and Baden Powell at the Teatro da Praia | |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1950s, South Zone of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Derivative forms |

|

Bossa nova (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈbɔsɐ ˈnɔvɐ] ) is a relaxed style of samba[nb 1] developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[2] It is mainly characterized by a calm syncopated rhythm with chords and fingerstyle mimicking the beat of a samba groove, as if it was a simplification and stylization on the guitar of the rhythm produced by a samba school band. Another defining characteristic of the style is the use of unconventional chords in some cases with complex progressions and "ambiguous" harmonies.[3][4] A common misconception is that these complex chords and harmonies were derived from jazz, but samba guitar players have been using similar arrangement structures since the early 1920s, indicating a case of parallel evolution of styles rather than a simple transference from jazz to bossa nova.[5][6] Nevertheless, bossa nova was influenced by jazz, both in the harmonies used and also by the instrumentation of songs, and today many bossa nova songs are considered jazz standards. The popularity of bossa nova has helped to renew samba and contributed to the modernization of Brazilian music in general.

One of the major innovations of bossa nova was the way to synthesize the rhythm of samba on the classical guitar.[2][6] According to musicologist Gilberto Mendes, the bossa nova was one of the "three rhythmic phases of samba", in which the "bossa beat" had been extracted by João Gilberto from the traditional samba.[5] The synthesis performed by Gilberto's guitar was a reduction of the "batucada" of samba, a stylization produced from one of the percussion instruments: the thumb stylized a surdo; the index, middle and ring fingers phrased like a tamborim.[6] In line with this thesis, musicians such as Baden Powell, Roberto Menescal, and Ronaldo Bôscoli also understand the bossa nova beat as being extracted from the tamborim play in the bateria.[7]

Etymology

[edit]

In Brazil, the word bossa is old-fashioned slang for something done with particular charm, natural flair or innate ability. As early as 1932, Noel Rosa used the word in a samba:

- "O samba, a prontidão e outras bossas são nossas coisas, são coisas nossas."

- ("Samba, readiness and other bossas are our things, are things from us.")

The phrase bossa nova, translated literally, means "new trend" or "new wave" in Portuguese.[9] The exact origin of the term bossa nova remained unclear for many decades, according to some authors. Within the artistic beach culture of the late 1950s in Rio de Janeiro, the term bossa was used to refer to any new "trend" or "fashionable wave". In his book Bossa Nova, Brazilian author Ruy Castro asserts that bossa was already in use in the 1950s by musicians as a word to characterize someone's knack for playing or singing idiosyncratically.[10]

Castro claims that the term bossa nova might have first been used in public for a concert given in 1957 by the Grupo Universitário Hebraico do Brasil ('Hebrew University Group of Brazil'). The authorship of the term bossa nova is attributed to the then-young journalist Moyses Fuks, who was promoting the event.[11] That group consisted of Sylvia Telles, Carlos Lyra, Nara Leão, Luiz Eça, Roberto Menescal, and others. Mr Fuks's description, fully supported by most of the bossa nova members, simply read "HOJE. SYLVIA TELLES E UM GRUPO BOSSA NOVA" ("Today. Sylvia Telles and a 'Bossa Nova' group"), since Sylvia Telles was the most famous musician in the group at that time.

In 1959, Nara Leão also participated in more than one embryonic display of bossa nova. These include the 1st Festival de Samba Session, conducted by the student union of Pontifícia Universidade Católica. This session was chaired by Carlos Diegues (later a prominent Cinema Novo film director), a law student whom Leão ultimately married.[12]

History

[edit]In 1959, the soundtrack to the film Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro) was released, which included the future Manhã de Carnaval, "The Morning of the Carnival". The style emerged at the time when samba-canção[nb 2] was the dominant rhythm in the Brazilian music scene.[14][15] Its first appearance was on the album Canção do Amor Demais, in which the singer Elizeth Cardoso recorded two compositions by the duo Antônio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes, "Outra Vez" and "Chega de Saudade", which were accompanied by João Gilberto's guitar. It was the first time that the Bahian musician presented the beat of his guitar that would become characteristic of the style.[2] By accompanying Cardoso's voice, Gilberto innovated in the way of pacing the rhythm, accentuating the weak times, to carry out a synthesis of the beat of samba to guitar.[2][16]

In 1959, João Gilberto's bossa album was released, containing the tracks "Chega de Saudade" and "Bim Bom".[16] Considered the landmark of the birth of bossa nova,[2][16] it also featured Gilberto's innovative way of singing samba, which was inspired by Dorival Caymmi.[17][18] With the LP Chega de Saudade, released in 1959, Gilberto consolidated the bossa nova as a new style of playing samba.[2][3] His innovative way of playing and singing samba, combined with the harmonies of Antônio Carlos Jobim and the lyrics of Vinicius de Moraes, found immediate resonance among musicians who were looking for new approaches to samba in Rio de Janeiro,[2][19] many of them were influenced by American jazz.[20]

In 1964 João Gilberto and Stan Getz released the Getz/Gilberto album. Then, it emerged an artistic movement around Gilberto and other professional artists such as Jobim, Moraes and Baden Powell, among others, which attracted young amateur musicians from the South Zone of Rio – such as Carlos Lyra, Roberto Menescal, Ronaldo Bôscoli and Nara Leão.[19][21] Jorge Ben wrote "Mas que Nada" in 1963, and Sérgio Mendes & Brazil 66 gained a bossa rock hit "Mas que Nada" in 1966.[22] It was inducted to the Latin Grammy Hall of Fame. In the 1960s, US jazz artists such as Stan Getz, Hank Mobley, Dave Brubeck, Zoot Sims, Paul Winter and Quincy Jones recorded bossa jazz albums.

Bossa nova continues to influence popular music around the world, from the 1960s to today. An example is the song "Break on Through (To the Other Side)" by American rock band The Doors, especially the drum beat. Drummer John Densmore has stated that he was very influenced by the sounds of Brazil when coming up with the drum part for the song.[23] A more recent reference is the Icelandic jazz pop singer Laufey and her hit song "From The Start", with its bossa nova infused rhythm.[24]

Instruments

[edit]Classical guitar

[edit]

Bossa nova is most commonly performed on the nylon-string classical guitar, played with the fingers rather than with a pick. Its purest form could be considered unaccompanied guitar with vocals, as created, pioneered, and exemplified by João Gilberto. Even in larger, jazz-like arrangements for groups, there is almost always a guitar that plays the underlying rhythm. Gilberto basically took one of the several rhythmic layers from a samba ensemble, specifically the tamborim, and applied it to the picking hand. According to Brazilian musician Paulo Bittencourt, João Gilberto, known for his eccentricity and obsessed by the idea of finding a new way of playing the guitar, sometimes locked himself in the bathroom, where he played one and the same chord for many hours in a row.[25]

Drums and percussion

[edit]As in samba, the surdo plays an ostinato figure on the downbeat of beat one, the "ah" of beat one, the downbeat of beat two and the "ah" of beat two. The clave pattern sounds very similar to the two-three or three-two son clave of Cuban styles such as mambo but is dissimilar in that the "two" side of the clave is pushed by an eighth note. Also important in the percussion section for bossa nova is the cabasa, which plays a steady sixteenth-note pattern. These parts are easily adaptable to the drum set, which makes bossa nova a rather popular Brazilian style for drummers.

Structure

[edit]Certain other instrumentations and vocals are also part of the structure of bossa nova. These include:

Bossa nova and samba

[edit]

Bossa nova has at its core a rhythm based on samba. Samba combines the rhythmic patterns and feel originating in afro-Brazilian slave communities. Samba's emphasis on the second beat carries through to bossa nova (to the degree that it is often notated in 2/4 time). However, unlike samba, bossa nova has no dance steps to accompany it.[26] When played on the guitar, in a simple one-bar pattern, the thumb plays the bass notes on 1 and 2, while the fingers pluck the chords in unison on the two eighth notes of beat one, followed by the second sixteenth note of beat two. Two-measure patterns usually contain a syncopation into the second measure. Syncopation is a common feature of bossa nova, giving it its distinct "swaying" motion. While jazz music, which is typically swung, also contains syncopation, bossa nova is typically played without swing, contrasting with jazz. As bossa nova composer Carlos Lyra describes it in his song "Influência do Jazz", the samba rhythm moves "side to side" while jazz moves "front to back". There's also some evidence indicating a musical influence of blues in bossa nova, even thought this effect is not immediately recognized in the genre structure.[27]

Vocals

[edit]Aside from the guitar style, João Gilberto's other innovation was the projection of the singing voice. Prior to bossa nova, Brazilian singers employed brassy, almost operatic styles. Now, the characteristic nasal vocal production of bossa nova is a peculiar trait of the caboclo folk tradition of northeastern Brazil.[28][29]

Themes and lyrics

[edit]The lyrical themes found in bossa nova include women, love, longing, homesickness, nature. Bossa Nova was often apolitical. The musical lyrics of the late 1950s depicted the easy life of the middle to upper-class Brazilians, though the majority of the population was in the working class. In conjunction with political developments of the early 1960s (especially the 1964 military coup d'état), the popularity of bossa nova was eclipsed by Música popular brasileira, a musical genre that appeared around the mid-1960s, featuring lyrics that were more politically charged and focused on the working class struggle.

Dance

[edit]Bossa nova was also a fad dance that corresponded to the music. It was introduced in the late 1950s and faded out in the mid-sixties.[30][unreliable source?] Bossa nova music, with its soft, sophisticated vocal rhythms and improvisations, is well suited for listening but failed to become dance music despite heavy promotion in the 1960s. The style of basic dance steps suited the music well. It was danced on "soft" knees that allowed for sideways sways with hip motions and it could be danced both solo and in pairs. About ten various simple step patterns were published.

A variant of basic 8-beat pattern was: "step forward, tap, step back, step together, repeat from the opposite foot". A variation of this pattern was a kind of slow samba walk, with "step together" above replaced by "replace". Box steps of rhumba and whisk steps of nightclub two step could be fitted with bossa-nova styling. Embellishments included placing one arm onto one's own belly and waving another arm at waist level in the direction of the sway, possibly with a finger click.[citation needed]

Notable bossa nova recordings

[edit]Albums

[edit]- Chega de Saudade (recorded 1959)

- O Amor, o Sorriso e a Flor (recorded 1960)

- Getz/Gilberto with Stan Getz (recorded 18 & 19 March 1963, released 1964)

- Luiz Bonfá Plays and Sings Bossa Nova (recorded December, 1962)

- The Composer of Desafinado Plays (recorded 9 & 10 May 1963)

- The Wonderful World of Antônio Carlos Jobim (recorded 1965)

- Wave (1967)

- Tide (1970)

Songs

[edit]- "Manhã de Carnaval," The morning of the carnival–Luiz Bonfa (1959), From Film "Black Orpheus" (Orpheu Negro)

- "The Girl From Ipanema"—Astrud Gilberto (1963)[31]

- "Blue Bossa"—Kenny Dorham (1963)

- "From the Start" —Laufey (2023)[32]

See also

[edit]- "Blame It on the Bossa Nova" – Eydie Gorme, 1963

- Cha-cha-chá

- Rumba

- Tango music

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The center of bossa nova remains, as for samba and subgenre of jazz, the song. Its intuition is lyrical and, even in the most sophisticated products, demands that one believes in a kind of spontaneity. Jazz, whose fundamental intuition is of a technical nature, privileges the chord".[1]

- ^ A slower tempo samba featured by a dominance of the melodic line over the main rhythmic[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Mammi 1992, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g EBC 2018.

- ^ a b Ratliff 2019.

- ^ Lopes & Simas 2015, p. 46.

- ^ a b Lopes & Simas 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Garcia 2019.

- ^ Garcia 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting music theory: a guide to the practice, p.28. ISBN 0-415-97440-2.

- ^ "Definition of Bossa Nova". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

Origin and Etymology: Portuguese, literally, 'new trend'. First Known Use: 1962

- ^ Castro, Ruy (transl. by Lysa Salsbury). Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World. 2000. 1st English language edition. A Capella Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Inc. ISBN 1-55652-409-9 First published in Brasil by Companhia das Letras (1990)

- ^ Afonso, Carlos Alberto (20 February 2010). "BLOG DA TOCA: 000026 - MOYSÉS FUKS na CALÇADA da FAMA de IPANEMA". BLOG DA TOCA. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Nara Leão". bossanova.folha.com.br. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Tatit 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Severiano 2009, p. 273.

- ^ Matos 2015, p. 130.

- ^ a b c Castro 2018.

- ^ Machado 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Caymmi 2001, p. 377.

- ^ a b Marcondes 1977, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Silva 2017, p. 133-137.

- ^ Lopes & Simas 2015, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Azevedo, Zeca. "As 100 Maiores Músicas Brasileiras – "Mas que Nada"". Rolling Stone Brasil. Spring. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ The Story of "Break on Through" by The Doors, retrieved 6 October 2023

- ^ "Laufey Crafts a Bossa Nova-Infused Love Triangle in "From The Start"", onestowatch.com, retrieved 19 June 2024

- ^ Bittencourt, Paulo. "What is bossa nova? Musician Paulo Bittencourt tells the story". medium.com.

- ^ Collin, Mark (26 June 2008). "Step one, pour yourself a drink ..." The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ McCann, Bryan (2007). "Blues and Samba: Another Side of Bossa Nova History". Luso-Brazilian Review. 44 (2): 21–49. doi:10.1353/lbr.2008.0005. S2CID 145569698.

- ^ "Caboclos refers to the mixed-race population (Indians or Africans 'imported' to the region during the slave era, and Europeans) who generally live along the Amazon's riverbanks." From "Two Cases on Participatory Municipal Planning on natural-resource management in the Brazilian Amazon", by GRET – Groupe de Recherche et d'Échanges Technologiques, France (in English)

- ^ "Bossa nova". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to Bossa Nova Dancing". www.heritageinstitute.com.

- ^ "The Girl From Ipanema". OldieLyrics. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Kalia, Ammar (3 March 2024). "TikTok jazz sensation Laufey: 'It's no longer about genre, it's about feeling and mood'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Carvalho, Hermínio Bello de (1986). Mudando de Conversa (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1ª ed.). São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

- Caymmi, Stella (2001). Dorival Caymmi: o mar e o tempo (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1ª ed.). São Paulo: Editora 34.

- Lopes, Nei; Simas, Luiz Antonio (2015). Dicionário da História Social do Samba (in Brazilian Portuguese) (2ª ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Machado, Regina Stela Barcelos (2011). A voz na canção popular brasileira: um estudo sobre a Vanguarda Paulista (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1ª ed.). São Paulo: Atelie Editorial.

- Marcondes, Marcos Antônio, ed. (1977). Enciclopédia da música brasileira - erudita, folclórica e popular (in Brazilian Portuguese) (1ª ed.). São Paulo: Art Ed.

- Severiano, Jairo (2009). Uma história da música popular brasileira: das origens à modernidade (in Brazilian Portuguese). São Paulo: Editora 34.

- Tatit, Luiz (1996). O cancionista: composição de canções no Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). São Paulo: Edusp.

- Mammi, Lorenzo (November 1992). "João Gilberto e a Utopia Social da Bossa Nova" (PDF). Novos Estudos Cebrap (in Brazilian Portuguese) (34). São Paulo: 63–70.

- Matos, Cláudia Neiva de (2015) [2013]. "Gêneros na canção popular: os casos do samba e do samba-canção". Artcultura (in Brazilian Portuguese). 15 (27). Uberlândia: Federal University of Uberlândia: 121–132.

- Silva, Rafael Mariano Camilo da (2017). Desafinado: dissonâncias nos discursos acerca da influência do Jazz na Bossa Nova (Master) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Uberlândia: Federal University of Uberlândia. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Castro, Ruy (9 July 2018). "Gravação de 'Chega de Saudade' foi um parto, mas elevou à eternidade som sem nome" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Garcia, Walter (1999). Bim Bom: a contradição sem conflitos de João Gilberto (in Brazilian Portuguese). São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

- Garcia, Walter (22 July 2019). "Batucada do samba cabia na mão de João Gilberto" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Ratliff, Ben (6 July 2019). "João Gilberto, an Architect of Bossa Nova, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times (published 6 July 2019). Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- "60 anos de Bossa Nova" (in Brazilian Portuguese). EBC. 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Castro, Ruy (transl. by Lysa Salsbury). Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World. 2000. 1st English language edition. A Capella Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Inc. ISBN 1-55652-409-9 First published in Brasil by Companhia das Letras. 1990.

- De Stefano, Gildo, Il popolo del samba, La vicenda e i protagonisti della storia della musica popolare brasiliana, Preface by Chico Buarque de Hollanda, Introduction by Gianni Minà, RAI-ERI, Rome 2005, ISBN 8839713484

- De Stefano, Gildo, Saudade Bossa Nova: musiche, contaminazioni e ritmi del Brasile, Preface by Chico Buarque, Introduction by Gianni Minà, Logisma Editore, Firenze 2017, ISBN 978-88-97530-88-6

- McGowan, Chris and Pessanha, Ricardo. The Brazilian Sound: Samba, Bossa Nova and the Popular Music of Brazil. 1998. 2nd edition. Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-545-3

- Perrone, Charles A. Masters of Contemporary Brazilian Song: MPB 1965–1985. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989.

- Mei, Giancarlo. Canto Latino: Origine, Evoluzione e Protagonisti della Musica Popolare del Brasile. 2004. Stampa Alternativa-Nuovi Equilibri. Preface by Sergio Bardotti; afterword by Milton Nascimento. (in Italian)

External links

[edit]- "It's 20 years ago bossa nova was released to the world at Carnegie Hall in New York" by Rénato Sergio, Manchete magazine, 1982 (in Portuguese)