Individualist anarchism in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anarchism in the United States |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau.[1] Other important individualist anarchists in the United States were Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Ezra Heywood, M. E. Lazarus, John Beverley Robinson, James L. Walker, Joseph Labadie, Steven Byington and Laurance Labadie.[2][3]

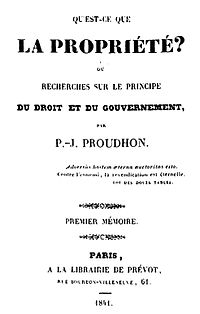

The first American anarchist publication was The Peaceful Revolutionist, edited by Warren, whose earliest experiments and writings predate Proudhon.[4] According to historian James J. Martin, the individualist anarchists were socialists, whose support for the labor theory of value made their libertarian socialist form of mutualism a free-market socialist alternative to both capitalism and Marxism.[5][6]

By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed.[7] In the 21st century, Kevin Carson describes his Studies in Mutualist Political Economy as "an attempt to revive individualist anarchist political economy, to incorporate the useful developments of the last hundred years, and to make it relevant to the problems of the twenty-first century".[8]

Overview

[edit]For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, American individualist anarchism "stresses the isolation of the individual – his right to his own tools, his mind, his body, and to the products of his labor. To the artist who embraces this philosophy it is 'aesthetic' anarchism, to the reformer, ethical anarchism, to the independent mechanic, economic anarchism. The former is concerned with philosophy, the latter with practical demonstration. The economic anarchist is concerned with constructing a society on the basis of anarchism. Economically he sees no harm whatsoever in the private possession of what the individual produces by his own labor, but only so much and no more. The aesthetic and ethical type found expression in the transcendentalism, humanitarianism, and romanticism of the first part of the nineteenth century, the economic type in the pioneer life of the West during the same period, but more favorably after the Civil War".[9]

Contemporary individualist anarchist Kevin Carson states that "[u]nlike the rest of the socialist movement, the individualist anarchists believed that the natural wage of labor in a free market was its product, and that economic exploitation could only take place when capitalists and landlords harnessed the power of the state in their interests. Thus, individualist anarchism was an alternative both to the increasing statism of the mainstream socialist movement, and to a classical liberal movement that was moving toward a mere apologetic for the power of big business".[10] It is for this reason that it has been suggested that in order to understand American individualist anarchism one must take into account "the social context of their ideas, namely the transformation of America from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist society, [...] the non-capitalist nature of the early U.S. can be seen from the early dominance of self-employment (artisan and peasant production). At the beginning of the 19th century, around 80% of the working (non-slave) male population were self-employed. The great majority of Americans during this time were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs". This made individualist anarchism "clearly a form of artisanal socialism [...] while communist anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism are forms of industrial (or proletarian) socialism".[11]

Historian Wendy McElroy reports that American individualist anarchism received an important influence of three European thinkers. According to McElroy, "[o]ne of the most important of these influences was the French political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose words "Liberty is not the Daughter But the Mother of Order" appeared as a motto on Liberty's masthead",[1] an influential individualist anarchist publication of Benjamin Tucker. McElroy further stated that "[a]nother major foreign influence was the German philosopher Max Stirner. The third foreign thinker with great impact was the British philosopher Herbert Spencer".[1] Other influences to consider include William Godwin's anarchism which "exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier". After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren, considered to be the first individualist anarchist. After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his ideological loyalties from socialism to anarchism which anarchist Peter Sabatini described as "no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism".[12]

Origins

[edit]Mutualism

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought which can be traced to the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market.[13] Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank which would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate only high enough to cover the costs of administration.[14] Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value which holds that when labour or its product is sold, in exchange it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[15] Some mutualists believe that if the state did not intervene, individuals would receive no more income than that in proportion to the amount of labor they exert as a result of increased competition in the marketplace.[16][17] Mutualists oppose the idea of individuals receiving an income through loans, investments and rent as they believe these individuals are not labouring. Some of them argue that if state intervention ceased, these types of incomes would disappear due to increased competition in capital.[18][19] Although Proudhon opposed this type of income, he expressed that he "never meant to [...] forbid or suppress, by sovereign decree, ground rent and interest on capital. I believe that all these forms of human activity should remain free and optional for all".[20]

Mutualists argue for conditional titles to land, whose private ownership is legitimate only so long as it remains in use or occupation (which Proudhon called "possession").[21] Proudhon's mutualism supports labor-owned cooperative firms and associations[22] for "we need not hesitate, for we have no choice [...] it is necessary to form an ASSOCIATION among workers [...] because without that, they would remain related as subordinates and superiors, and there would ensue two [...] castes of masters and wage-workers, which is repugnant to a free and democratic society" and so "it becomes necessary for the workers to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism".[23] As for capital goods (man-made and non-land, means of production), mutualist opinion differs on whether these should be common property and commonly managed public assets or private property in the form of worker cooperatives, for as long as they ensure the worker's right to the full product of their labor, mutualists support markets and property in the product of labor, differentiating between capitalist private property (productive property) and personal property (private property).[24][25]

Following Proudhon, mutualists are libertarian socialists who consider themselves to part of the market socialist tradition and the socialist movement. However, some contemporary mutualists outside the classical anarchist tradition abandoned the labor theory of value and prefer to avoid the term socialist due to its association with state socialism throughout the 20th century. Nonetheless, those contemporary mutualists "still retain some cultural attitudes, for the most part, that set them off from the libertarian right. Most of them view mutualism as an alternative to capitalism, and believe that capitalism as it exists is a statist system with exploitative features".[26] Mutualists have distinguished themselves from state socialism and do not advocate state ownership over the means of production. Benjamin Tucker said of Proudhon that "though opposed to socializing the ownership of capital, Proudhon aimed nevertheless to socialize its effects by making its use beneficial to all instead of a means of impoverishing the many to enrich the few [...] by subjecting capital to the natural law of competition, thus bringing the price of its own use down to cost".[27]

Josiah Warren

[edit]

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[2] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published,[4] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[4]

Warren was a follower of Robert Owen and joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana. Josiah Warren termed the phrase "cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item.[28] Therefore, "[h]e proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce".[2] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years, after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included Utopia and Modern Times. Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society, published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories.[29] Catalan historian Xavier Diez reports that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand and the intentional communities started by them.[30]

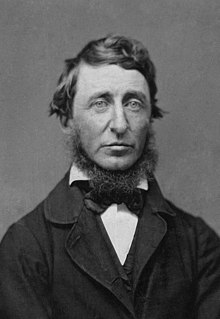

Henry David Thoreau

[edit]

The American version of individualist anarchism has a strong emphasis on individual sovereignty.[3] Some individualist anarchists such as Henry David Thoreau[31][32] describe a simple right of "disunion" from the state.[33]

"Civil Disobedience" (Resistance to Civil Government) is an essay by Thoreau that was first published in 1849. It argues that people should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that people have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. Thoreau was motivated in part by his disgust with slavery and the Mexican–American War. It would influence Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Buber and Leo Tolstoy through its advocacy of nonviolent resistance.[34] It is also the main prescedent for anarcho-pacifism.[34]

Anarchism started to have an ecological view mainly in the writings of American individualist anarchist and transcendentalist Thoreau. In his book Walden, he advocates simple living and self-sufficiency among natural surroundings in resistance to the advancement of industrial civilization.[35] Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and anarcho-primitivism represented today in John Zerzan. For George Woodcock, this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid-19th century".[35] John Zerzan himself included the text "Excursions" (1863) by Thoreau in his edited compilation of anti-civilization writings called Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections from 1999.[36] Walden made Thoreau influential in the European individualist anarchist green current of anarcho-naturism.[35]

William Batchelder Greene

[edit]

William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist, individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister, soldier and promoter of free banking in the United States. Greene is best known for the works Mutual Banking (1850), which proposed an interest-free banking system, and Transcendentalism, a critique of the New England philosophical school. For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent [...] that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. [...] William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[37]

After 1850, Greene became active in labor reform.[37] Greene was "elected vice-president of the New England Labor Reform League, the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking, and in 1869 president of the Massachusetts Labor Union".[37] He then published Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875).[37] He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order."[37] His "associationism [...] is checked by individualism. [...] 'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage – the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".[37]

Stephen Pearl Andrews

[edit]

Stephen Pearl Andrews was an individualist anarchist and close associate of Josiah Warren. Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance.

Andrews said that when individuals act in their own self-interest, they incidentally contribute to the well-being of others. He maintained that it is a "mistake" to create a "state, church or public morality" that individuals must serve rather than pursuing their own happiness. In Love, Marriage and Divorce, and the Sovereignty of the Individual, he says to "[g]ive up [...] the search after the remedy for the evils of government in more government. The road lies just the other way – toward individualism and freedom from all government. [...] Nature made individuals, not nations; and while nations exist at all, the liberties of the individual must perish".

Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey reports that "Steven Pearl Andrews [...] was not a fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America & adopted a lot of fourierist principles & practices [...], a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized Abolitionism, Free Love, spiritual universalism, [Josiah] Warren, & Fourier into a grand utopian scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy". Bey further states that Andrews was "instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th St. in New York, & 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts & the North American Phalanx in New Jersey) – in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious (for 'Free Love') & finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (& Victoria Woodhull) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International, expelled by Marx for its anarchist, feminist, & spiritualist tendencies.[38]

Free love

[edit]An important current within American individualist anarchism is free love.[39] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women such as with marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[39]

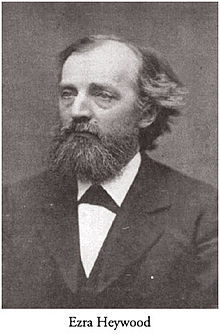

The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois Waisbrooker.[40] However, there also existed Angela Heywood and Ezra Heywood's The Word (1872–1890, 1892–1893).[39]

M. E. Lazarus was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.[39] Hutchins Hapgood was an American journalist, author, individualist anarchist and philosophical anarchist who was well known within the Bohemian environment of around the start of the 20th century New York City. He advocated free love and committed adultery frequently. Hapgood was a follower of the German philosophers Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche.[41]

Lucifer the Lightbearer

[edit]

According to Harman, the mission of Lucifer the Lightbearer was "to help woman to break the chains that for ages have bound her to the rack of man-made law, spiritual, economic, industrial, social and especially sexual, believing that until woman is roused to a sense of her own responsibility on all lines of human endeavor, and especially on lines of her special field, that of reproduction of the race, there will be little if any real advancement toward a higher and truer civilization". The name was chosen because "Lucifer, the ancient name of the Morning Star, now called Venus, seems to us unsurpassed as a cognomen for a journal whose mission is to bring light to the dwellers in darkness".

In February 1887, the editors and publishers of Lucifer were arrested after the journal ran afoul of the Comstock Act for the publication of a letter condemning forced sex within marriage, which the author identified as rape. The Comstock Act specifically prohibited the discussion of marital rape. A Topeka district attorney eventually handed down 216 indictments. In February 1890, Harman, now the sole producer of Lucifer, was again arrested on charges resulting from a similar article written by a New York physician. As a result of the original charges, Harman would spend large portions of the next six years in prison.

In 1896, Lucifer was moved to Chicago, but legal harassment continued. The United States Postal Service—then known as the United States Post Office Department—seized and destroyed numerous issues of the journal and, in May 1905, Harman was again arrested and convicted for the distribution of two articles—"The Fatherhood Question" and "More Thoughts on Sexology" by Sara Crist Campbell. Sentenced to a year of hard labor, the 75-year-old editor's health deteriorated greatly. After 24 years in production, Lucifer ceased publication in 1907 and became the more scholarly American Journal of Eugenics.

They also had many opponents, and Moses Harman spent two years in jail after a court determined that a journal he published was "obscene" under the notorious Comstock Law. In particular, the court objected to three letters to the editor, one of which described the plight of a woman who had been raped by her husband, tearing stitches from a recent operation after a difficult childbirth and causing severe hemorrhaging. The letter lamented the woman's lack of legal recourse. Ezra Heywood, who had already been prosecuted under the Comstock Law for a pamphlet attacking marriage, reprinted the letter in solidarity with Harman and was also arrested and sentenced to two years in prison.

Ezra Heywood

[edit]Ezra Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren such as the True Civilization (1869) and William Batchelder Greene. In 1872, at a convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual Liberty publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations.

The Word

[edit]

The Word was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood's from (1872–1890, 1892–1893), issued first from Princeton and then from Cambridge, Massachusetts.[39] The Word was subtitled "A Monthly Journal of Reform" and included contributions from Josiah Warren, Benjamin Tucker and J.K. Ingalls. Initially, The Word presented free love as a minor theme which was expressed within a labor reform format, but the publication later evolved into an explicitly free love periodical.[39] At some point, Tucker became an important contributor but later became dissatisfied with the journal's focus on free love since he desired a concentration on economics. In contrast, Tucker's relationship with Heywood grew more distant. Yet, when Heywood was imprisoned for his pro-birth control stand from August to December 1878 under the Comstock laws, Tucker abandoned the Radical Review in order to assume editorship of Heywood's The Word. After Heywood's release from prison, The Word openly became a free love journal; it flouted the law by printing birth control material and openly discussing sexual matters. Tucker's disapproval of this policy stemmed from his conviction that "[l]iberty, to be effective, must find its first application in the realm of economics".[39]

M. E. Lazarus

[edit]M. E. Lazarus was an American individualist anarchist from Guntersville, AL. He is the author of several essays and anarchist pamphlettes including Land Tenure: Anarchist View (1889). A famous quote from Lazarus is "Every vote for a governing office is an instrument for enslaving me". Lazarus was also an intellectual contributor to Fourierism and the Free Love movement of the 1850s, a social reform group that called for, in its extreme form, the abolition of institutionalized marriage.

In Lazarus' 1852 essay, Love vs Marriage, he argued that marriage as an institution was akin to "legalized prostitution", oppressing women and men by allowing loveless marriages contracted for economic or utilitarian reasons to take precedence over true love.[42][43][44]

Freethought

[edit]Freethought as a philosophical position and as activism was important in North American individualist anarchism. In the United States, freethought was "a basically anti-Christian, anti-clerical movement, whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of Freethought and, for a time, The Truth Seeker. E.C. Walker was co-editor of the excellent free-thought / free love journal Lucifer, the Light-Bearer".[1] Many of the anarchists were "ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty. [...] The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself".[1]

Boston anarchists

[edit]

Another form of individualist anarchism was found in the United States as advocated by the Boston anarchists.[45] By default, American individualists had no difficulty accepting the concepts that "one man employ another" or that "he direct him," in his labor but rather demanded that "all natural opportunities requisite to the production of wealth be accessible to all on equal terms and that monopolies arising from special privileges created by law be abolished."[46]

They believed state monopoly capitalism (defined as a state-sponsored monopoly)[47] prevented labor from being fully rewarded. Voltairine de Cleyre, summed up the philosophy by saying that the anarchist individualists "are firm in the idea that the system of employer and employed, buying and selling, banking, and all the other essential institutions of Commercialism, centred upon private property, are in themselves good, and are rendered vicious merely by the interference of the State".[48]

Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including intellectual property rights and possession versus property in land.[49][50][51] A major schism occurred later in the 19th century when Tucker and some others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights—as espoused by Lysander Spooner—and converted to an "egoism" modeled upon Stirner's philosophy.[50] Lysander Spooner besides his individualist anarchist activism was also an important anti-slavery activist and became a member of the First International.[52]

Some Boston anarchists, including Benjamin Tucker, identified themselves as socialists which in the 19th century was often used in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. "the labor problem").[53] The Boston anarchists such as Tucker and his followers are considered socialists due to their opposition to usury.[11] This is because as the modern economist Jim Stanford states there are many different kinds of competitive markets such as market socialism and capitalism is only one type of a market economy.[54]

Liberty (1881–1908)

[edit]

Liberty was a 19th-century market socialist[55] Anarchist and Libertarian Socialist[56] periodical published in the United States by Benjamin Tucker, from August 1881 to April 1908. The periodical was instrumental in developing and formalizing the American individualist anarchist philosophy through publishing essays and serving as a format for debate. Contributors included Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Dyer Lum, Joshua K. Ingalls, John Henry Mackay, Victor Yarros, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, James L. Walker, J. William Lloyd, Florence Finch Kelly, Voltairine de Cleyre, Steven T. Byington, John Beverley Robinson, Jo Labadie, Lillian Harman, and Henry Appleton. Included in its masthead is a quote from Pierre Proudhon saying that liberty is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order".

Within the labor movement

[edit]George Woodcock reports that the American individualist anarchists Lysander Spooner and William B. Greene had been members of the socialist First International[57] Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's Liberty were also important labor organizers of the time.

Joseph Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet. In 1883 Labadie embraced individualist anarchism, a non-violent doctrine. He became closely allied with Benjamin Tucker, the country's foremost exponent of that doctrine, and frequently wrote for the latter's publication, Liberty. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing [their] fellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes." However, he supported community cooperation, as he supported community control of water utilities, streets, and railroads.[58] Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for the clemency of the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators. In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president, and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers.

Dyer Lum was a 19th-century American individualist anarchist, labor activist and poet.[59] A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s,[60] he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.[61] Lum was a prolific writer who wrote a number of key anarchist texts, and contributed to publications including Mother Earth, Twentieth Century, Liberty (Benjamin Tucker's individualist anarchist journal), The Alarm (the journal of the International Working People's Association) and The Open Court among others. Lum's political philosophy was a fusion of individualist anarchist economics—"a radicalized form of laissez-faire economics" inspired by the Boston anarchists—with radical labor organization similar to that of the Chicago anarchists of the time.[62] Herbert Spencer and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon influenced Lum strongly in his individualist tendency.[62] He developed a "mutualist" theory of unions and as such was active within the Knights of Labor and later promoted anti-political strategies in the American Federation of Labor.[62] Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism, and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and radicalize workers[62] as he came to believe that revolution would inevitably involve a violent struggle between the working class and the employing class.[61] Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery.[61] Kevin Carson has praised Lum's fusion of individualist laissez-faire economics with radical labor activism as "creative" and described him as "more significant than any in the Boston group".[62]

Egoism

[edit]

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract". After converting to egoist individualism, Tucker that "it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off. [...] Man's only right to land is his might over it."[63] In adopting Stirnerite egoism by 1886, Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. Tucker comments that "[s]o bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly".[64]

Wendy McElroy writes that "[s]everal periodicals were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism. They included: I published by C.L. Swartz, edited by W.E. Gordak and J.W. Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle 'A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology'.[64]

Among those American anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker, John Beverley Robinson, Steven T. Byington, Hutchins Hapgood, James L. Walker, Victor Yarros and E. H. Fulton.[64] John Beverley Robinson wrote an essay called "Egoism" in which he states that "[m]odern egoism, as propounded by Stirner and Nietzsche, and expounded by Ibsen, Shaw and others, is all these; but it is more. It is the realization by the individual that they are an individual; that, as far as they are concerned, they are the only individual".[65] Steven T. Byington was a one-time proponent of Georgism who later converted to egoist stirnerist positions after associating with Benjamin Tucker. He is known for translating two important anarchist works into English from German: Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own and Paul Eltzbacher's Anarchism: Exponents of the Anarchist Philosophy (also published by Dover with the title The Great Anarchists: Ideas and Teachings of Seven Major Thinkers).

James L. Walker and The Philosophy of Egoism

[edit]James L. Walker, sometimes known by the pen name Tak Kak, was one of the main contributors to Benjamin Tucker's Liberty. He published his major philosophical work called Philosophy of Egoism in the May 1890 to September 1891 in issues of the publication Egoism.[66] James L. Walker published the work The Philosophy of Egoism in which he argued that egosim "implies a rethinking of the self-other relationship, nothing less than 'a complete revolution in the relations of mankind' that avoids both the 'archist' principle that legitimates domination and the 'moralist' notion that elevates self-renunciation to a virtue. Walker describes himself as an 'egoistic anarchist' who believed in both contract and cooperation as practical principles to guide everyday interactions".[67] For Walker, the egoist rejects notions of duty and is indifferent to the hardships of the oppressed whose consent to their oppression enslaves not only them, but those who do not consent.[68] The egoist comes to self-consciousness, not for the God's sake, not for humanity's sake, but for his or her own sake.[69] For him, "[c]ooperation and reciprocity are possible only among those who are unwilling to appeal to fixed patterns of justice in human relationships and instead focus on a form of reciprocity, a union of egoists, in which person each finds pleasure and fulfillment in doing things for others".[70] Walker thought that "what really defines egoism is not mere self-interest, pleasure, or greed; it is the sovereignty of the individual, the full expression of the subjectivity of the individual ego".[71]

Influence of Friedrich Nietzsche

[edit]Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Stirner were frequently compared by French "literary anarchists" and anarchist interpretations of Nietzschean ideas appear to have also been influential in the United States.[72] One researcher notes that "translations of Nietzsche's writings in the United States very likely appeared first in Liberty, the anarchist journal edited by Benjamin Tucker". He adds that "Tucker preferred the strategy of exploiting his writings, but proceeding with due caution: 'Nietzsche says splendid things, – often, indeed, Anarchist things, – but he is no Anarchist. It is of the Anarchists, then, to intellectually exploit this would-be exploiter. He may be utilized profitably, but not prophetably'".[73]

Italian Americans

[edit]Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States[74] by Italian born individualists such as Giuseppe Ciancabilla and others who advocated for violent propaganda by the deed there. Anarchist historian George Woodcock reports the incident in which the important Italian social anarchist Errico Malatesta became involved "in a dispute with the individualist anarchists of Paterson, who insisted that anarchism implied no organization at all, and that every man must act solely on his impulses. At last, in one noisy debate, the individual impulse of a certain Ciancabilla directed him to shoot Malatesta, who was badly wounded but obstinately refused to name his assailant".[75]

Enrico Arrigoni

[edit]Enrico Arrigoni, pseudonym of Frank Brand, was an Italian American individualist anarchist Lathe operator, house painter, bricklayer, dramatist and political activist influenced by the work of Max Stirner.[76][77] He took the pseudonym "Brand" from a fictional character in one of Henrik Ibsen's plays.[77] In the 1910s he started becoming involved in anarchist and anti-war activism around Milan.[77] From the 1910s until the 1920s he participated in anarchist activities and popular uprisings in various countries including Switzerland, Germany, Hungary, Argentina and Cuba.[77] He lived from the 1920s onwards in New York City and there he edited the individualist anarchist eclectic journal Eresia in 1928. He also wrote for other American anarchist publications such as L' Adunata dei refrattari, Cultura Obrera, Controcorrente and Intessa Libertaria.[77] During the Spanish Civil War, he went to fight with the anarchists but was imprisoned and was helped on his release by Emma Goldman.[76][77] Afterwards Arrigoni became a longtime member of the Libertarian Book Club in New York City.[77] He died in New York City when he was 90 years old on December 7, 1986.[77]

Since 1945

[edit]Murray Bookchin has identified post-left anarchy as a form of individualist anarchism in Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm where he says he identifies "a shift among Euro-American anarchists away from social anarchism and toward individualist or lifestyle anarchism. Indeed, lifestyle anarchism today is finding its principal expression in spray-can graffiti, post-modernist nihilism, antirationalism, neoprimitivism, anti-technologism, neo-Situationist 'cultural terrorism,' mysticism, and a 'practice' of staging Foucauldian 'personal insurrections'".[78] Post-left anarchist Bob Black in his long critique of Bookchin's philosophy called Anarchy after leftism said about post-left anarchy that "It is, unlike Bookchinism, individualistic" in the sense that if the freedom and happiness of the individual – i.e., each and every really existing person, every Tom, Dick and Murray – is not the measure of the good society, what is?"[79]

A strong relationship does exist with post-left anarchism and the work of individualist anarchist Max Stirner. Jason McQuinn says that "when I (and other anti-ideological anarchists) criticize ideology, it is always from a specifically critical, anarchist perspective rooted in both the skeptical, individualist-anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner.[80] Also Bob Black and Feral Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher strongly adhere to stirnerist egoist anarchism. Bob Black has humorously suggested the idea of "marxist stirnerism".[81]

Hakim Bey has said that "[f]rom Stirner's 'Union of Self-Owning Ones' we proceed to Nietzsche's circle of 'Free Spirits' and thence to Charles Fourier's 'Passional Series', doubling and redoubling ourselves even as the Other multiplies itself in the eros of the group".[82] Bey also wrote that "[t]he Mackay Society, of which Mark & I are active members, is devoted to the anarchism of Max Stirner, Benj. Tucker & John Henry Mackay. [...] The Mackay Society, incidentally, represents a little-known current of individualist thought which never cut its ties with revolutionary labor. Dyer Lum, Ezra & Angela Haywood represent this school of thought; Jo Labadie, who wrote for Tucker's Liberty, made himself a link between the American 'plumb-line' anarchists, the 'philosophical' individualists, & the syndicalist or communist branch of the movement; his influence reached the Mackay Society through his son, Laurance. Like the Italian Stirnerites (who influenced us through our late friend Enrico Arrigoni) we support all anti-authoritarian currents, despite their apparent contradictions".[83]

As far as posterior individualist anarchists, Jason McQuinn used for some time the pseudonym Lev Chernyi in honor of the Russian individualist anarchist of the same name while Feral Faun has quoted Italian individualist anarchist Renzo Novatore[84] and has translated Novatore[85] as well as the young Italian individualist anarchist Bruno Filippi.[86] Egoism has had also a strong influence on insurrectionary anarchism as can be seen in the work of the American insurrectionist Wolfi Landstreicher.

In 1995, Lansdstreicher writing as Feral Faun wrote:

In the game of insurgence – a lived guerilla war game – it is strategically necessary to use identities and roles. Unfortunately, the context of social relationships gives these roles and identities the power to define the individual who attempts to use them. So I, Feral Faun, became [...] an anarchist, [...] a writer, [...] a Stirner-influenced, post-situationist, anti-civilization theorist, [...] if not in my own eyes, at least in the eyes of most people who've read my writings.[87]

Left-wing market anarchism, a form of left-libertarianism, individualist anarchism[88] and libertarian socialism,[89][90] is associated with scholars such as Kevin Carson,[91][92] Roderick T. Long,[93][94] Charles Johnson,[95] Brad Spangler,[96] Samuel Edward Konkin III,[97] Sheldon Richman,[98][99][100] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[101] and Gary Chartier,[102] who stress the value of radically free markets, termed freed markets to distinguish them from the common conception which these libertarians believe to be riddled with statist and capitalist privileges.[103] Referred to as left-wing market anarchists[104] or market-oriented left-libertarians,[100] proponents of this approach strongly affirm the classical liberal ideas of self-ownership and free markets while maintaining that taken to their logical conclusions, these ideas support anti-capitalist, anti-corporatist, anti-hierarchical, pro-labor positions in economics; anti-imperialism in foreign policy; and thoroughly liberal or radical views regarding such cultural issues as gender, sexuality and race.[105][106]

The genealogy of contemporary market-oriented left-libertarianism, sometimes labeled left-wing market anarchism,[107] overlaps to a significant degree with that of Steiner–Vallentyne left-libertarianism as the roots of that tradition are sketched in the book The Origins of Left-Libertarianism.[108] Carson–Long-style left-libertarianism is rooted in 19th century mutualism and in the work of figures such as the socialist Thomas Hodgskin and the individualist anarchists Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner. While with notable exceptions market-oriented libertarians after Tucker tended to ally with the political right, relationships between such libertarians and the New Left thrived in the 1960s, laying the groundwork for modern left-wing market anarchism.[109] Left wing market anarchism identifies with left-libertarianism[110] which names several related yet distinct approaches to politics, society, culture and political and social theory which stress both individual freedom and social justice. Unlike right-libertarians, left-libertarians believe that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights,[111][112] and maintain that natural resources (land, oil, gold, trees) ought to be held in some egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.[112] Those left-libertarians who support property do so under different property norms[113][114][115][116] and theories,[117][118][119] or under the condition that recompense is offered to the local or global community.[112]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Wendy McElroy. "The culture of individualist anarchist in Late-nineteenth century America".

- ^ a b c Palmer, Brian (29 December 2010). "What do anarchists want from us?" Slate.com.

- ^ a b Madison, Charles A. (1945). "Anarchism in the United States". Journal of the History of Ideas. 6 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 46–66. doi:10.2307/2707055. JSTOR 2707055.

- ^ a b c Bailie, William (1906). Josiah Warren: The First American Anarchist – A Sociological Study Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co. p. 20.

- ^ Martin, James J. (1970). Men Against the State. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher. pp. viii, ix, 209. ISBN 9780879260064

- ^ McKay, Iain, ed. (2012) [2008]. An Anarchist FAQ. Vol. I/II. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 9781849351225.

- ^ Avrich, Paul. 2006. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. p. 6.

- ^ Carson, Kevin (2006). "Preface" Archived 2016-10-01 at the Wayback Machine. Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. Charlestone, North Carolina: BookSurge Publishing. ISBN 9781419658693. "Preface". Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2020.. Retrieved 26 September 2020 – via the Mutualist: Free Market Anti-Capitalism website.

- ^ Eunice Minette Schuster. Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism. Archived February 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kevin Carson. Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective. BookSurge. 2008. p. 1.

- ^ a b "G.1.4 Why is the social context important in evaluating Individualist Anarchism?" An Anarchist FAQ. Archived March 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Peter Sabatini. "Libertarianism: Bogus Anarchy".

- ^ "Introduction". Mutualist: Free-Market Anti-Capitalism. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Miller, David. 1987. "Mutualism." The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraph 15.

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraphs 9, 10 & 22.

- ^ Carson, Kevin, 2004, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, chapter 2 (after Meek & Oppenheimer).

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraph 19.

- ^ Carson, Kevin, 2004, Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, chapter 2 (after Ricardo, Dobb & Oppenheimer).

- ^ Solution of the Social Problem, 1848–49.

- ^ Swartz, Clarence Lee. What is Mutualism? VI. Land and Rent

- ^ Hymans, E., Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, pp. 190–91,

Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Broadview Press, 2004, pp. 110, 112 - ^ General Idea of the Revolution, Pluto Press, pp. 215–16, 277

- ^ Crowder, George (1991). Classical Anarchism: The Political Thought of Godwin, Proudhon, Bakunin, and Kropotkin. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9780198277446. "The ownership [anarchists oppose] is basically that which is unearned [...] including such things as interest on loans and income from rent. This is contrasted with ownership rights in those goods either produced by the work of the owner or necessary for that work, for example his dwelling-house, land and tools. Proudhon initially refers to legitimate rights of ownership of these goods as 'possession,' and although in his latter work he calls this 'property,' the conceptual distinction remains the same."

- ^ Hargreaves, David H. (2019). Beyond Schooling: An Anarchist Challenge. London: Routledge. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9780429582363. "Ironically, Proudhon did not mean literally what he said. His boldness of expression was intended for emphasis, and by 'property' he wished to be understood what he later called 'the sum of its abuses'. He was denouncing the property of the man who uses it to exploit the labour of others without any effort on his own part, property distinguished by interest and rent, by the impositions of the non-producer on the producer. Towards property regarded as 'possession' the right of a man to control his dwelling and the land and tools he needs to live, Proudhon had no hostility; indeed, he regarded it as the cornerstone of liberty, and his main criticism of the communists was that they wished to destroy it."

- ^ "A Mutualist FAQ: A.4. Are Mutualists Socialists?". Mutualist: Free-Market Anti-Capitalism. Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin (1926) [1890]. Individual Liberty: Selections from the Writings of Benjamin R. Tucker. New York: Vanguard Press. Archived 17 January 1999 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2020 – via Flag.Blackened.Net.

- ^ Warren, Josiah. Equitable Commerce. "A watch has a cost and a value. The COST consists of the amount of labor bestowed on the mineral or natural wealth, in converting it into metals ..."

- ^ Madison, Charles A. (January 1945). "Anarchism in the United States". Journal of the History of Ideas. 6: 1. p. 53.

- ^ Diez, Xavier. L'ANARQUISME INDIVIDUALISTA A ESPANYA 1923–1938 p. 42.

- ^ Johnson, Ellwood. The Goodly Word: The Puritan Influence in America Literature, Clements Publishing, 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences, edited by Edwin Robert Anderson Seligman, Alvin Saunders Johnson, 1937, p. 12.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David (1996). Thoreau: Political Writings. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-47675-1.

- ^ a b "RESISTING THE NATION STATE the pacifist and anarchist tradition by Geoffrey Ostergaard". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ a b c "Su obra más representativa es Walden, aparecida en 1854, aunque redactada entre 1845 y 1847, cuando Thoreau decide instalarse en el aislamiento de una cabaña en el bosque, y vivir en íntimo contacto con la naturaleza, en una vida de soledad y sobriedad. De esta experiencia, su filosofía trata de transmitirnos la idea que resulta necesario un retorno respetuoso a la naturaleza, y que la felicidad es sobre todo fruto de la riqueza interior y de la armonía de los individuos con el entorno natural. Muchos han visto en Thoreau a uno de los precursores del ecologismo y del anarquismo primitivista representado en la actualidad por Jonh Zerzan. Para George Woodcock(8), esta actitud puede estar también motivada por una cierta idea de resistencia al progreso y de rechazo al materialismo creciente que caracteriza la sociedad norteamericana de mediados de siglo XIX.""LA INSUMISIÓN VOLUNTARIA. EL ANARQUISMO INDIVIDUALISTA ESPAÑOL DURANTE LA DICTADURA Y LA SEGUNDA REPÚBLICA (1923–1938)" by Xavier Diez Archived May 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections by John Zerzan (editor)

- ^ Hakim Bey. "The Lemonade Ocean & Modern Times".

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Free Love Movement and Radical Individualism By Wendy McElroy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ^ Joanne E. Passet, "Power through Print: Lois Waisbrooker and Grassroots Feminism," in: Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, James Philip Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006; pp. 229–50.

- ^ Biographical Essay by Dowling, Robert M. American Writers, Supplement XVII. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008

- ^ Freedman, Estelle B., "Boston Marriage, Free Love, and Fictive Kin: Historical Alternatives to Mainstream Marriage." Organization of American Historians Newsletter, August 2004. http://www.oah.org/pubs/nl/2004aug/freedman.html#Anchor-23702

- ^ Guarneri, Carl J., The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1991.

- ^ Stoehr, Taylor, ed., Free Love in America: A Documentary History. New York: AMS, 1979.

- ^ Levy, Carl. "Anarchism". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09.

- ^ Madison, Charles A. "Anarchism in the United States." Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol 6, No 1, January 1945, p. 53.

- ^ Schwartzman, Jack. "Ingalls, Hanson, and Tucker: Nineteenth-Century American Anarchists." American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 5 (November 2003). p. 325.

- ^ de Cleyre, Voltairine. Anarchism. Originally published in Free Society, 13 October 1901. Published in Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre, edited by Sharon Presley, SUNY Press 2005, p. 224.

- ^ Spooner, Lysander. The Law of Intellectual Property Archived May 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Watner, Carl (1977). "Benjamin Tucker and His Periodical, Liberty" (PDF). 30 July 2014. (868 KB). Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 308.

- ^ Watner, Carl. ""Spooner Vs. Liberty" (PDF). 22 January 2010." (1.20 MB) in The Libertarian Forum. March 1975. Volume VII, No 3. ISSN 0047-4517. pp. 5–6.

- ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: a history of anarchist ideas and movements (1962). p. 459.

- ^ Brooks, Frank H. 1994. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. p. 75.

- ^ Stanford, Jim. Economics for Everyone: A Short Guide to the Economics of Capitalism. Ann Arbor: MI., Pluto Press. 2008. p. 36.

- ^ McKay, Iain. An Anarchist FAQ. AK Press. Oakland. 2008. pp 60.

- ^ McKay, Iain. An Anarchist FAQ. AK Press. Oakland. 2008. pp 22.

- ^ Woodcock, G. (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Melbourne: Penguin. p. 460.

- ^ Martin, James J. (1970). Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908. Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher.

- ^ Schuster, Eunice (1999). Native American Anarchism. City: Breakout Productions. p. 168 (footnote 22). ISBN 978-1-893626-21-8.

- ^ Johnpoll, Bernard; Harvey Klehr (1986). Biographical Dictionary of the American Left. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-24200-7.

- ^ a b c Crass, Chris. "Voltairine de Cleyre – a biographical sketch". Infoshop.org. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ a b c d e Carson, Kevin. "May Day Thoughts: Individualist Anarchism and the Labor Movement". Mutualist Blog: Free Market Anti-Capitalism. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Tucker, Instead of a Book, p. 350

- ^ a b c "Wendy Mcelroy. "Benjamin Tucker, Individualism, & Liberty: Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order"". Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ^ "Egoism" by John Beverley Robinson

- ^ McElroy, Wendy. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books. 2003. p. 55

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 163

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 165

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 166

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 164

- ^ John F. Welsh. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. p. 167

- ^ O. Ewald, "German Philosophy in 1907", in The Philosophical Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, Jul., 1908, pp. 400–26; T. A. Riley, "Anti-Statism in German Literature, as Exemplified by the Work of John Henry Mackay", in PMLA, Vol. 62, No. 3, Sep., 1947, pp. 828–43; C. E. Forth, "Nietzsche, Decadence, and Regeneration in France, 1891–95", in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 54, No. 1, Jan., 1993, pp. 97–117; see also Robert C. Holub's Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist, an essay available online at the University of California, Berkeley website.

- ^ Robert C. Holub, Nietzsche: Socialist, Anarchist, Feminist Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "it was in times of severe social repression and deadening social quiescence that individualist anarchists came to the foreground of libertarian activity – and then primarily as terrorists. In France, Spain, and the United States, individualistic anarchists committed acts of terrorism that gave anarchism its reputation as a violently sinister conspiracy." [1]Murray Bookchin. Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. 1962

- ^ a b Enrico Arrigoni at the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia Archived May 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h [2]Paul Avrich. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America

- ^ Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm by Murray Bookchin

- ^ Anarchy after Leftism by Bob Black

- ^ "What is Ideology?" by Jason McQuinn

- ^ "Theses on Groucho Marxism" by Bob Black

- ^ Immediatism by Hakim Bey. AK Press. 1994. p. 4 Archived December 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hakim Bey. "An esoteric interpretation of the I.W.W. preamble"

- ^ Anti-politics.net Archived 2009-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, "Whither now? Some thoughts on creating anarchy" by Feral Faun

- ^ Towards the creative nothing and other writings by Renzo Novatore Archived August 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The rebel's dark laughter: the writings of Bruno Filippi.

- ^ "The Last Word" by Feral Faun

- ^ Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia.

- ^ "It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism." Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. p. Back cover

- ^ "But there has always been a market-oriented strand of libertarian socialism that emphasizes voluntary cooperation between producers. And markets, properly understood, have always been about cooperation. As a commenter at Reason magazine's Hit&Run blog, remarking on Jesse Walker's link to the Kelly article, put it: "every trade is a cooperative act." In fact, it's a fairly common observation among market anarchists that genuinely free markets have the most legitimate claim to the label "socialism.""."Socialism: A Perfectly Good Word Rehabilitated" by Kevin Carson at website of Center for a Stateless Society

- ^ Carson, Kevin A. (2008). Organization Theory: A Libertarian Perspective. Charleston, SC:BookSurge.

- ^ Carson, Kevin A. (2010). The Homebrew Industrial Revolution: A Low-Overhead Manifesto. Charleston, SC:BookSurge.

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2000). Reason and Value: Aristotle versus Rand. Washington, DC:Objectivist Center

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2008). "An Interview With Roderick Long"

- ^ Johnson, Charles W. (2008). "Liberty, Equality, Solidarity: Toward a Dialectical Anarchism." Anarchism/Minarchism: Is a Government Part of a Free Country? In Long, Roderick T. and Machan, Tibor Aldershot:Ashgate pp. 155–88.

- ^ Spangler, Brad (15 September 2006). "Market Anarchism as Stigmergic Socialism Archived May 10, 2011, at archive.today."

- ^ Konkin III, Samuel Edward. The New Libertarian Manifesto Archived 2014-06-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon (23 June 2010). "Why Left-Libertarian?" The Freeman. Foundation for Economic Education.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon (18 December 2009). "Workers of the World Unite for a Free Market Archived July 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine." Foundation for Economic Education.

- ^ a b Sheldon Richman (3 February 2011). "Libertarian Left: Free-market anti-capitalism, the unknown ideal Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine." The American Conservative. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (2000). Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism. University Park, PA:Pennsylvania State University Press.

- ^ Chartier, Gary (2009). Economic Justice and Natural Law. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Gillis, William (2011). "The Freed Market." In Chartier, Gary and Johnson, Charles. Markets Not Capitalism. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. pp. 19–20.

- ^ Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Gary Chartier and Charles W. Johnson (eds). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Minor Compositions; 1st edition (November 5, 2011)

- ^ Gary Chartier has joined Kevin Carson, Charles Johnson, and others (echoing the language of Benjamin Tucker and Thomas Hodgskin) in maintaining that, because of its heritage and its emancipatory goals and potential, radical market anarchism should be seen – by its proponents and by others – as part of the socialist tradition, and that market anarchists can and should call themselves "socialists." See Gary Chartier, "Advocates of Freed Markets Should Oppose Capitalism," "Free-Market Anti-Capitalism?" session, annual conference, Association of Private Enterprise Education (Cæsar's Palace, Las Vegas, NV, April 13, 2010); Gary Chartier, "Advocates of Freed Markets Should Embrace 'Anti-Capitalism'"; Gary Chartier, Socialist Ends, Market Means: Five Essays. Cp. Tucker, "Socialism."

- ^ Chris Sciabarra is the only scholar associated with this school of left-libertarianism who is skeptical about anarchism; see Sciabarra's Total Freedom

- ^ Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner. The origins of Left Libertarianism. Palgrave. 2000

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2006). "Rothbard's 'Left and Right': Forty Years Later." Rothbard Memorial Lecture, Austrian Scholars Conference.

- ^ Related, arguably synonymous, terms include libertarianism, left-wing libertarianism, egalitarian-libertarianism, and libertarian socialism.

- Sundstrom, William A. "An Egalitarian-Libertarian Manifesto Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine."

- Bookchin, Murray and Biehl, Janet (1997). The Murray Bookchin Reader. New York:Cassell. p. 170.

- Sullivan, Mark A. (July 2003). "Why the Georgist Movement Has Not Succeeded: A Personal Response to the Question Raised by Warren J. Samuels." American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 62:3. p. 612.

- ^ Vallentyne, Peter; Steiner, Hillel; Otsuka, Michael (2005). "Why Left-Libertarianism Is Not Incoherent, Indeterminate, or Irrelevant: A Reply to Fried" (PDF). Philosophy and Public Affairs. 33 (2). Blackwell Publishing, Inc.: 201–215. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.2005.00030.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-03. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ a b c Narveson, Jan; Trenchard, David (2008). "Left libertarianism". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 288–89. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n174. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ Schnack, William (13 November 2015). "Panarchy Flourishes Under Geo-Mutualism". Center for a Stateless Society. Archived 10 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Byas, Jason Lee (25 November 2015). "The Moral Irrelevance of Rent". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Carson, Kevin (8 November 2015). "Are We All Mutualists?" Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Gillis, William (29 November 2015). "The Organic Emergence of Property from Reputation". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Bylund, Per (2005). Man and Matter: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Justification of Ownership in Land from the Basis of Self-Ownership (PDF). LUP Student Papers (master's thesis). Lund University. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Long, Roderick T. (2006). "Land-locked: A Critique of Carson on Property Rights" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (1): 87–95.

- ^ Verhaegh, Marcus (2006). "Rothbard as a Political Philosopher" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (4): 3.

Further reading

[edit]- Brooks, Frank H. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick. 1994.

- Chartier, Gary; Johnson, Charles W. (2011). Markets Not Capitalism: Individualist Anarchism Against Bosses, Inequality, Corporate Power, and Structural Poverty. Brooklyn, NY:Minor Compositions/Autonomedia.

- Men against the State: the expositors of individualist anarchism in America, 1827–1908 (1970) by James Joseph Martin.

- Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism by Eunice Minette Schuster.

- Rocker, Rudolf. Pioneers of American Freedom: Origin of Liberal and Radical Thought in America. Rocker Publishing Committee. 1949.

- Nettlau, Max (1996). "Individualist anarchism in the United States, England and elsewhere. The early American libertarian intellectuals". In Heiner M Becker (ed.). A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. ISBN 0-900384-89-1. OCLC 37529250.