Borsh

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

Borsh

Borshi | |

|---|---|

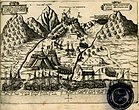

Borsh Castle | |

| Coordinates: 40°3′45″N 19°51′24″E / 40.06250°N 19.85667°E | |

| Country | |

| County | Vlorë |

| Municipality | Himarë |

| Municipal unit | Lukovë |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 2,500 |

| Demonym | Borshiot/e |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Borsh (Albanian pronunciation: [ˈbɔɾʃ]; Albanian definite form: Borshi, [ˈbɔɾʃi]) is a maritime village, in the Albanian Riviera, in the former Lukovë municipality, Vlorë County, Albania.[1] At the 2015 local government reform, it became part of the Himarë municipality.[2] The village is inhabited by ethnic Albanians,[3] many of whom have traditionally been Bektashi. In Borsh, the Lab dialect of Albanian is spoken.

Borsh borders with Fterra, Qeparo, Piqeras, Kuç, Çorraj, Kalasa, Zhulat, Tatzat, and has a population of 2,500 registered inhabitants.[citation needed]

History

[edit]The region which Borshi is located was part of the Chaonia of the ancient region of Epirus. Borshi was probably fortified from antiquity and it belonged to Kemara (modern Himara) then part of the Chaonian tribal state, one of the main ancient Greek tribes in Epirus.[4] In the Hellenistic period Borshi was a northwestern-most stronghold of the fortification system of Chaonia after Himara.[5] The Chaonian fortification in Borsh of which Phoenice served as centre controlled a crucial road that connected Chaonia and southern Illyria.[6]

The castle remained in use in Roman times and was refortified by the Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. Nothing is known of the settlement in the Byzantine era, until it is mentioned as Sopotos in 1258 when it was part of the Despotate of Epirus that grew out of the failing Byzantine empire. Borsh then went through a period of considerable turmoil, changing hands several times between the Despotate of Epirus and Norman crusades invaders before being taken by the Turks in 1431.

Fifty years later it was captured by Albanians led by Skanderbeg's son Gjon Kastrioti II, but was retaken by the Turks eleven years later and heavily refortified. On June 10, 1570 the castle of Sopot was taken by James Celsi, Proveditor of the Venetian navy, who left after leaving in charge the commander of Nauplion, Emmanuel Mormoris. This also caused part of the nearby Himariotes to submit to Venetian rule.[7] The next year the Ottoman army recaptured it and took Mormori as a prisoner.

The 18th century was a turbulent economic time and due to Orthodox revolts and conflicts with Orthodox powers such as the Russian Empire, Ottoman governors at times applied pressures including drastic tax raises on the local Christian population as well as other pressures caused towns to convert.[8] Borsh converted in 1744 and followed it up by raiding nearby Piqeras, which remained Christian.[9][10]

The fortress was renovated again by Ali Pasha Tepelena, and it is these fortifications that visitors can view by taking the half-hour walk up to the 'castle rock', the limestone mount clearly visible above the old village. During Ali Pasha's reign, there were 700 houses at Borsh, and below the castle mount you can see a ruined mosque of Hajji Bendo and a madrese (a Muslim theological school), both of which were damaged in Ali Pasha's wars but survived, only to be destroyed in fighting after 1912 when the Turks left the region.

Between 1912 and 1914, serious inter-ethnic conflict took place between Greeks and Albanians, and significant portion of the old village was destroyed, however some buildings remain in fine condition. Modern Borsh was built after that, but became seriously depopulated, firstly due to malaria, and following severe reprisal killings by Germans in World War II. However, depopulation was balanced by an influx of refugees from Vlora, fleeing into partisan territory from the city which was heavily contested until late in the war.In 1914 the greek military massacred albanians in Borsh [11]

Geography

[edit]Geographical scope

[edit]Borsh is a coastal village in southern Albania, in the district of Vlore. The geographic coordinates of the village are 40.0667° N, 19.9389° E.

Borsh is located about 25 km south of the city of Vlore and is situated in a mountainous area, with coastal beaches and crystal-clear waters. The village of Borsh is located on a coastal stretch of about 7 km and is surrounded by hills with heights of around 900 meters above sea level.

There are many beautiful natural areas in the Borsh region, such as the Llogara National Park, the Bënça River Gorge, the Borsh River, and the Borsh Castle area. This area has a warm Mediterranean climate, with an average temperature of 25 degrees Celsius during the summer and 10-12 degrees Celsius during the winter.

Borsh is a popular tourist destination for its beaches, beautiful nature, and its connections to the region's traditional and folk culture.

Climate

[edit]Borsh experiences a hot-summer mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). Precipitation in Borsh mainly falls in the winter, with little rain in the summer months. Borsh experiences mild winters and hot, dry summers. The average annual temperature is 13.3 °C or 55.9 °F, with 1598 mm or 62.9 inches of precipitation per year.[12]

| Climate data for Bosh (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

37.1 (98.8) |

41.8 (107.2) |

41.3 (106.3) |

37.6 (99.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.3 (52.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.1 (61.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 162.1 (6.38) |

139.8 (5.50) |

105.6 (4.16) |

73.9 (2.91) |

37.7 (1.48) |

18.5 (0.73) |

13.3 (0.52) |

20.2 (0.80) |

102.6 (4.04) |

219.4 (8.64) |

263.3 (10.37) |

248.7 (9.79) |

1,405.1 (55.32) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.2 | 75.3 | 73.9 | 72.1 | 69.8 | 67.4 | 66.5 | 68.1 | 72.0 | 74.6 | 76.5 | 76.8 | 72.4 |

| Source: NOAA[13] | |||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]

The village is very stable and growing in prosperity thanks to tourism and olive oil production. The economy of Borsh is mainly based on tourism, livestock farming, and agriculture.

In the summer, Borsh is a popular tourist destination, especially for its beautiful beaches and rich natural environment. Tourism is the main source of income for the town and offers many business opportunities for hoteliers, restaurants, and other tourism-related businesses.

In addition to tourism, Borsh has an economy based on livestock farming and agriculture. Crops such as olives, oranges, lemons, grapes, peppers, and other food plants are cultivated. Livestock farming is also important in the rural areas of Borsh, with animals such as goats, sheep, and cows.

Overall, the economy of Borsh is small and developing, but tourism and the agricultural sector may offer growth opportunities in the future.

Borsh has gained popularity due to its beach, which is the largest beach in the Ionian sea (7 km).

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]The Lab dialect spoken in Borsh was reported by Albanian linguist M.Totoni to possess nasal vowels,[14] a characteristic that was previously thought to have been the diagnostic difference between the major Tosk and Gheg divisions, whereby Tosk dialects such as Borsh's lab dialect were previously thought to have all lost nasal vowels when they split from Gheg dialects, which retained the nasality feature.[15]

Notable people

[edit]Following is a list of notable people from Borsh.

- Perparim Kabo-Professor Doctor of Philosophical Sciences

- Beqir Haçi-Poet,publicist,translator

- Arsen Hoxha-Football referee

- Nebil Çika- Journalist

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Location of Borsh". Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ^ "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF) (in Albanian). p. 6376. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Kallivretakis, Leonidas (1995). "Η ελληνική κοινότητα της Αλβανίας υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής γεωγραφίας και δημογραφίας [The Greek Community of Albania in terms of historical geography and demography." In Nikolakopoulos, Ilias, Kouloubis Theodoros A. & Thanos M. Veremis (eds). Ο Ελληνισμός της Αλβανίας [The Greeks of Albania]. University of Athens. p. 51. " AM Αλβανοί Μουσουλμάνοι”; p.53. “BORSH ΜΠΟΡΣΙ 1243 AM"

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History: The fourth century B.C. Cambridge University Press. 1994. pp. 437–443. ISBN 9780521233484.

To the north the Chaonians ... The state represented by 'Kemara' in the list of hosts had two centres, Himarrë and Borsh, both probably fortified ... Thus the north-west Greek-speaking tribes were at a half-way stage economically and politically, retaining the vigour of a tribal society and reaching out in a typically Greek manner towards a larger political organization.

- ^ Çipa, Kriledjan (2017). "Himara in the Hellenistic period. Analysis of Historical, epigraphic and Archaeological Sources". Novaensia. 28. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ *Çipa, Kriledjan (2020). "The fortified settlement of Borshi and its role in Chaonia fortification system". In Luigi Maria Caliò; Gian Michele Gerogiannis; Maria Kopsacheili (eds.). Fortificazioni e società nel Mediterraneo occidentale: Albania e Grecia settentrionale [Fortifications and Societies in the Western Mediterranean: Albania and Northern Greece]. Quasar. p. 216. ISBN 9788854910430.

- ^ Hill, George (2010). A History of Cyprus. Cambridge University Press. p. 911. ISBN 978-1-108-02064-0.

- ^ Giakoumis, Kosta (2010).“The Orthodox Church in Albania During the Ottoman Rule (15th-19th century)”, in Rathberger A. [ed.] (2010), Religion und Kultur im albanisch-sprachigen Südosteuropa, preface by O. Schmitt, Frankfurt am Main: Pro Oriente – Peter Lang, pp. 69-110. Pages 75-77.

- ^ *Kallivretakis, Leonidas (2003). "Νέα Πικέρνη Δήμου Βουπρασίων: το χρονικό ενός οικισμού της Πελοποννήσου τον 19ο αιώνα (και η περιπέτεια ενός πληθυσμού) [Nea Pikerni of Demos Vouprassion: The chronicle of a 19th century Peloponnesian settlement (and the adventures of a population)]". In Panagiotopoulos, Vasilis; Kallivretakis, Leonidas; Dimitropoulos, Dimitris; Kokolakis, Mihalis; Olibitou, Eudokia (eds.). Πληθυσμοί και οικισμοί του ελληνικού χώρου: ιστορικά μελετήματα [Populations and settlements of the Greek villages: historical essays] (PDF). Athens: Institute for Neohellenic Research. pp. 221–242. ISSN 1105-0845.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780198142539.

- ^ https://top-channel.tv/english/borsh-commemorates-greek-massacres/

- ^ "Borsh climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Borsh water temperature - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "Bosh Climate Normals 1981–2010". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Totoni, Menela (1964). “E folmja e bregdetit të poshtëm”, Studime Filologjike I, Tiranë, 1964, p. 136.

- ^ Paçarizi , Rrahman (2008). Albanian Language Archived 2017-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Page 102.