Swing Time (film)

| Swing Time | |

|---|---|

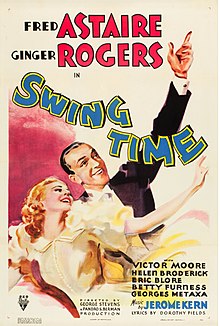

Theatrical release poster by William Rose | |

| Directed by | George Stevens |

| Screenplay by | Howard Lindsay Allan Scott Contributing writers (uncredited):[1] Dorothy Yost Ben Holmes Anthony Veiller Rian James |

| Story by | Erwin S. Gelsey "Portrait of John Garnett" (screen story)[1] |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Starring | Fred Astaire Ginger Rogers |

| Cinematography | David Abel |

| Edited by | Henry Berman |

| Music by | Jerome Kern (music) Dorothy Fields (lyrics) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $886,000[3] |

| Box office | $2.6 million[3] |

Swing Time is a 1936 American musical comedy film, the sixth of ten starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Directed by George Stevens for RKO, it features Helen Broderick, Victor Moore, Betty Furness, Eric Blore and Georges Metaxa, with music by Jerome Kern and lyrics by Dorothy Fields. Set mainly in New York City, the film follows a gambler and dancer, "Lucky" (Astaire), who is trying to raise money to secure his marriage when he meets a dance instructor, Penny (Rogers), and begins dancing with her; the two soon fall in love and are forced to reconcile their feelings.

Noted dance critic Arlene Croce considers Swing Time to be Astaire and Rogers's best dance musical,[4] a view shared by John Mueller[5] and Hannah Hyam.[6] It features four dance routines that are each regarded as masterpieces. According to The Oxford Companion to the American Musical, Swing Time is "a strong candidate for the best of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals". The Oxford Companion says that, although the screenplay is contrived, it "left plenty of room for dance and all of it was superb. ... Although the movie is remembered as one of the great dance musicals, it also boasts one of the best film scores of the 1930s."[7] "Never Gonna Dance" is often singled out as the partnership's and collaborator Hermes Pan's most profound achievement in filmed dance, while "The Way You Look Tonight" won the Academy Award for Best Original Song, and Astaire topped the U.S. pop chart with it in 1936. Jerome Kern's score, the first of two that he composed specially for Astaire films, contains three of his most memorable songs.[8]

The film's plot has been criticized, though,[9] as has the performance of Metaxa.[4][5] More praised is Rogers's acting and dancing performance.[10] Rogers credited much of the film's success to Stevens: "He gave us a certain quality, I think, that made it stand out above the others."[5] Swing Time also marked the beginning of a decline in popularity of the Astaire–Rogers partnership among the general public, with box-office receipts falling faster than usual after a successful opening.[11] Nevertheless, the film was a sizable hit, costing $886,000, grossing over $2,600,000 worldwide, and showing a net profit of $830,000. The partnership never regained the creative heights scaled in this and previous films.[12]

In 1999, Swing Time was listed as one of Entertainment Weekly's top 100 films. In 2004, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". In AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition), it is ranked at No. 90.

Plot

[edit]John "Lucky" Garnett is a gambler and dancer who is ready to marry Margaret Watson. Not wanting him to retire, the other members of his dance act deliberately sabotage the event. "Pop" Cardetti takes Lucky's trousers to be altered by sewing cuffs, while the others begin a crap game. After the tailor refuses to modify the pants, Pop returns with them, unaltered. Margaret's father phones to say that he has sent everyone home, but the call is intercepted. When Lucky finally leaves for the wedding, his troupe bets the bankroll that he will not get married. Lucky mollifies Margaret's father by saying that he was "earning" $200. Judge Watson tells Lucky that he must earn $25,000 to demonstrate his good intentions.

At the train station, Lucky's dance troupe takes all of his money, except for his lucky quarter because he did not get married. Pop and Lucky board the first freight train to New York. Lucky meets Penny when he asks for change for his lucky quarter, so that he can buy cigarettes for Pop. The cigarette machine dumps a load of coins, so they follow Penny and offer to repurchase the quarter, but she is in no mood to deal with them. Pop sneaks the quarter out of her purse when she drops her things, but she thinks that Lucky did it. Lucky insists on following Penny to her job as a dance school instructor. He accepts a dancing lesson from her agency to apologize. After a disastrous lesson ("Pick Yourself Up"), Penny tells him to "save his money". Her boss, Mr. Gordon, overhears and fires her. He also fires Mabel Anderson for complaining that Pop ate her sandwich. Lucky dances with Penny to prove how much that she has taught him. Gordon gives Penny back her job, and sets up an audition with the owner of the Silver Sandal nightclub.

Lucky and Pop check into the hotel where Penny and Mabel live. Lucky fails to win a tuxedo for the audition by playing strip piquet. They miss the audition, and Penny gets mad at Lucky again. He and Pop picket in front of Penny's apartment door for a week. Mabel intervenes, and Penny forgives him, agreeing to a second audition. At the Silver Sandal, bandleader Ricardo Romero, who wants to marry Penny, refuses to play for them. The club owner cannot force him because he lost Romero's contract in a bet with Club Raymond. At the casino, Pop warns Lucky that he is about to win enough money to marry Margaret. He takes his bet off the table. The club owner wagers Ricardo's contract on a cut of the cards. Seeing that Raymond intends to cheat, Pop cheats too, and Lucky wins the contract.

Lucky and Penny are dance partners, but he avoids seeing her alone. He lacks the nerve to tell her about Margaret. Mabel arranges a trip to the country. Lucky resists the temptation to snuggle in a snow-covered gazebo, prompting "A Fine Romance". Pop lets the truth slip about Margaret. In the remodeled Silver Sandal, Penny refuses another proposal from Ricardo. Mabel dares her to give Lucky "a great big kiss". They do kiss behind a dressing room door. Pop lets his sleight of hand become known to Raymond, who insists on competing with Lucky for the contract. He loses. Margaret arrives, and Lucky asks her to meet him the next day. While Lucky is indecisive, Penny becomes heartbroken. Lucky finds her in the deserted club, where he learns that she has agreed to marry Ricardo. Asked about the future, he sings "Never Gonna Dance", segueing without dialogue into their dance to "The Way You Look Tonight".

The next day, Margaret tells Lucky that she wants to marry someone else. Everyone laughs until Pop announces that Ricardo and Penny will be married that afternoon. They rush to intervene and manage to pull off the trouser gag. While waiting for the nonexistent alteration, Ricardo struggles to keep up a pair of baggy pants. An infectious round of laughter causes Penny to call off the wedding, having been wooed by Lucky.

Cast

[edit]- Fred Astaire as John "Lucky" Garnett

- Ginger Rogers as Penelope "Penny" Carroll

- Victor Moore as Edwin "Pop" Cardetti

- Eric Blore as Mr. Gordon

- Helen Broderick as Mabel Anderson

- Betty Furness as Margaret Watson

- Georges Metaxa as Ricardo "Ricky" Romero

- Landers Stevens as Judge Watson

- Abe Reynolds as Schmidt the tailor (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Initially, the working titles for the film were I Won't Dance and Never Gonna Dance, but studio executives worried that no one would come see a musical in which no one danced, so the title was changed.[13] Pick Yourself Up was also considered as a title, as were 15 other possibilities.[1]

Erwin Gelsey's original screen story was purchased by RKO and, in November 1935, Gelsey was hired to adapt the story. Although he did not receive any screen credit, he was under consideration for screenplay credit as late as July 1936. Howard Lindsay wrote the first draft of the screenplay, which was considerably rewritten by Allan Scott. Before shooting started in April 1936, Scott was called back from New York to write additional dialogue.[1]

Astaire spent almost eight weeks preparing for the film's dance numbers.[1]

The "Bojangles of Harlem" number, a tribute to Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, was the last part of the film to be shot, because of the special effects required. To create the effect that Astaire was dancing with three shadows of himself that were larger-than-life, Astaire had to be filmed dancing in front of a blank white screen on which a powerful light projected his shadow. This footage was tripled in the film lab. Next, Astaire was filmed performing under normal lighting in front of another white screen while watching a projection of the dancing shadow, and the four shots were optically combined. In its entirety, the sequence took three full days of shooting; the whole film took several weeks longer to shoot than the normal Astaire–Rogers film.[1]

The New York street scenes were shot on Paramount's back lot, the train station interiors and exteriors at the Los Angeles Santa Fe Railroad Station, and the freight yard scene was shot in downtown Los Angeles.[1]

The car used during the "New Amsterdam Inn" number is a 1935 Auburn 851 Phaeton Sedan.[14]

Musical numbers

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

- "Pick Yourself Up": The first of Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields's standards is a polka sung and danced by Astaire and Rogers. It is also a technical tour-de-force, with the basic polka embellished by syncopated rhythms, and overlaid with tap decoration. In particular, Rogers recaptures the spontaneity and commitment that she first displayed in the "I'll Be Hard to Handle" number from Roberta; that film's score was originally written by Kern for the Broadway stage.

- "The Way You Look Tonight": Kern and Fields's Oscar-winning foxtrot is sung by Astaire, seated at a piano, while Ginger is busy washing her hair in a side room. Astaire conveys a sunny yet nostalgic romanticism, but later, when they dance to "Never Gonna Dance", the pair will create a mood of sombre poignancy. As evidence of its enduring appeal, the song has been featured in modern cinema and television. It is featured in the films Chinatown and My Best Friend's Wedding, and it plays a prominent role as an important element in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine series finale, "What You Leave Behind".

- "Waltz in Swing Time": Described by one critic as "the finest piece of pure dance music ever written for Astaire", this is the most virtuosic partnered romantic duet Astaire ever committed to film. Kern was always reluctant to compose in the swing style, so the film's orchestrator, Robert Russell Bennett — a longtime Kern associate on Broadway — composed the number using some themes provided by Kern.[1] The song's interlude, a ¾ treatment of "The Way You Look Tonight", was added by rehearsal pianist Hal Borne. Bennett recalled Kern's request to attend to the number ("see what Freddie [Astaire] wants") to Arlene Croce in 1976,[15] and later in a letter to John Mueller; the published sheet music notes that the waltz was "constructed and arranged" by Bennett. The dance is a nostalgic celebration of love, in the form of a syncopated waltz with tap overlays — a concept that Astaire would rework in the "Belle of New York" segment of the "Currier and Ives" routine from The Belle of New York. In the midst of this complex routine, Astaire and Rogers find time to gently poke fun at notions of elegance, in a reminder of a similar episode in "Pick Yourself Up".

- "A Fine Romance": Kern and Fields's third standard, a quickstep to Fields's bittersweet lyrics, is sung alternately by Rogers and Astaire, with Rogers providing an object lesson in acting while a bowler-hatted Astaire at times appears to be impersonating Stan Laurel. Never a man to discard a favorite piece of fine clothing, Astaire wears the same coat in the opening scene of Holiday Inn.

- "Bojangles of Harlem": Kern, Bennett and Borne combined their talents to produce a jaunty instrumental piece ideally suited to Astaire, who here — while overtly paying tribute to Bill Robinson — actually broadens his tribute to African-American tap dancers by dancing in the style of Astaire's one-time teacher, John W. Bubbles, and dressing in the style of the character, Sportin' Life, a role that Bubbles played in Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.[1] Dorothy Fields recounted how Astaire managed to inspire the reluctant Kern by visiting his home and singing while dancing on and around his furniture. It is the only number in which Astaire — again bowler-hatted — appears in blackface. The idea of using trick photography to show Astaire dancing with three of his shadows was invented by Hermes Pan[16]: 9 (who also choreographed the opening chorus), after which Astaire dances a short opening solo that features poses mimicking and satirizing Al Jolson,[citation needed] all of which was captured by Stevens in one take. A two-minute solo follows, with Astaire dancing with his shadows; it took three days to shoot. Astaire's choreography exercises every limb, and makes extensive use of hand-clappers. Hermes Pan earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Dance Direction.

- "Never Gonna Dance": After Astaire sings Fields's closing line of Kern's haunting ballad, they begin the acknowledgement phase of the dance, replete with a poignant nostalgia for their now-doomed affair, in which the music changes to "The Way You Look Tonight", and they dance slowly in a manner reminiscent of the opening part of "Let's Face The Music And Dance" from Follow the Fleet. At the end of this episode, Astaire adopts a crestfallen, helpless pose. They begin the denial phase, and again the music changes and speeds up, this time to the "Waltz In Swing Time" while the dancers separate to twirl their way up their respective staircases, escaping to the platform at the top of the Silver Sandal Set — an elaborate Art Deco-influenced Hollywood Moderne creation of Carroll Clark and John Harkrider. The music switches to a frantic, fast-paced, recapitulation of "Never Gonna Dance" as the pair dance a last, desperate and virtuosic routine before Rogers flees and Astaire repeats his pose of dejection, in a final acceptance of the affair's end. This final routine was shot 47 times in one day before Astaire was satisfied, with Rogers's feet left bruised and bleeding by the time they finished.[16]: 12

- Finale duet: At the end of the film, Astaire and Rogers sing shortened versions of "A Fine Romance" and "The Way You Look Tonight" simultaneously (with altered lyrics). Harmonies were slightly altered so that the two songs fit well together.

Musical notes

- Kern and Fields also wrote an additional song, "It's Not in the Cards", as a full opening number, but it was cut, heard only momentarily at the conclusion of the first scene, and later as background music.[1]

- Kern was hired to write seven songs, for which he was paid $50,000 and a gross percentage up to $37,500. Astaire requested that two of the songs be swing numbers, but the weak version of "Bojangles of Harlem" that he delivered remained unacceptable, despite Astaire having spent several hours tap-dancing in Kern's hotel room in an attempt to loosen it up. Kern required the services of Robert Russell Bennet, and, during rehearsal, Astaire's rehearsal pianist, Hal Borne, contributed ideas. Although Astaire requested that Borne receive credit for his contribution, Kern was insistent that Borne receive no credit, was not to compose any music, and was not to be paid for writing any music. Bennett also received no credit in the film, but the sheet music for "Waltz in Swing Time" credits him with the construction and arrangement.[1]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]According to RKO records, the film made $1,624,000 in the U.S. and Canada, and $994,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $830,000.[3]

It was the 15th most popular film at the British box office in 1935–1936.[17]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97%, based on 29 reviews, with an average rating of 8.58/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire are brilliant in Swing Time, one of the duo's most charming and wonderfully choreographed films."[18] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 91 out of 100, based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[19]

- American Dancer, November 1936: "Astaire's dancing can no longer be classified as mere tap, because it is such a perfect blend of tap, modern and ballet, with a generous share of Astaire's personality and good humor... Rogers is vastly improved... but she cannot, as yet, vie with Astaire's amazing agility, superb grace and sophisticated charm. With Astaire one feels, with each succeeding picture, that surely his dancing has reached perfection and marks the end of invention of new steps: and yet he seems to go forward with ease and apparent nonchalance."[20]

- Dance Magazine, November 1936, by Joseph Arnold Kaye: "Much has been written about Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Swing Time except, perhaps, one thing: Astaire and Rogers are the picture; everything else seems to have been put in to fill the time between swings. Dance routines are fresh and interesting, dance is superb. When Hollywood will learn to make a dance picture as good as the dancing, we cannot even guess."[20]

- Variety, September 2, 1936, by Abel: "Perhaps a shade under previous par, but it's another box-office and personal winner from the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers combo... Film's 103 minutes running time could have been pared to advantage but Swing Time will swing 'em past the wickets in above-average tempo."[20]

Awards and honors

[edit]At the 1937 Academy Awards, Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields won the award for Best Music, Original Song, and Hermes Pan was nominated but did not win for his choreography for "Bojangles of Harlem".

In 1999, Entertainment Weekly named Swing Time as one of the top 100 films, and in 2004, the film was included in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". In 2007, the American Film Institute ranked Swing Time at No. 90 on their 10th anniversary list of 100 Years...100 Movies.[1]

Adaptations

[edit]A Broadway musical based on the film, Never Gonna Dance, used much of Kern and Fields's original score. The show, which had a book by Jeffrey Hatcher, began performances on October 27, 2003, running for 44 previews and 84 performances. It opened on December 4, 2003, and closed on February 15, 2004. It was directed by Michael Greif and choreographed by Jerry Mitchell.[21][1]

Allusions in other works

[edit]The film lends its title to Zadie Smith's 2016 novel Swing Time, in which it is a recurring plot device.[22]

Home media

[edit]Region 1

In 2005, a digitally restored version of Swing Time was released, available both separately (in Region 1) and as part of The Astaire & Rogers Collection, Vol.1 from Warner Home Video. These releases feature a commentary by John Mueller, author of Astaire Dancing – The Musical Films.

On June 11, 2019, The Criterion Collection released the movie in the United States on Blu-ray and DVD formats.

Region 2

In 2003, a digitally restored version of Swing Time (in Region 2) was released both separately and as part of The Fred and Ginger Collection, Vol. 1 from Universal Studios, which controls the rights to the RKO Astaire–Rogers pictures in the UK and Ireland. These releases feature an introduction by Astaire's daughter, Ava Astaire McKenzie.

The movie has also been released on Blu-ray in the UK by The Criterion Collection.

See also

[edit]- You Were Never Lovelier – 1942 film by William A. Seiter

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Swing Time at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ Brown, Gene (1995). Movie Time: A Chronology of Hollywood and the Movie Industry from Its Beginnings to the Present. New York: Macmillan. p. 130. ISBN 0-02-860429-6.

- ^ a b c Richard Jewel (1994) 'RKO Film Grosses: 1931–1951', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Vol. 14 No. 1, p.55

- ^ a b Croce, pp.98-115

- ^ a b c Mueller, pp.100-113

- ^ Hyam, Hannah (2007). Fred and Ginger – The Astaire-Rogers Partnership 1934–1938. Brighton: Pen Press Publications. ISBN 978-1-905621-96-5.

- ^ Hischak, Thomas. "Swing Time". The Oxford Companion to the American Musical, Oxford University Press 2009. Oxford Reference Online, accessed September 25, 2016 (requires subscription)

- ^ Mueller, p. 101n: "In a 1936 letter George Gershwin was somewhat patronizing about the music: 'Although I don't think Kern has written any outstanding song hits, I think he did a very credible job with the music and some of it is really quite delightful. Of course, he never was really quite ideal for Astaire and I take that into consideration'."

- ^ Mueller, p. 101: "the story is riddled with inconsistencies, implausibilities, contrivances, omissions, and irrationalities," Croce, p. 102: "discontinuities in the plot," also see Hyam, p. 46.

- ^ Mueller, p. 103: "her finest in the series".

- ^ Astaire, Fred (1959). Steps in Time. London: Heinemann. pp. 218–228. ISBN 0-241-11749-6.

- ^ Croce, p. 104: "Swing Time is an apotheosis."

- ^ Hischak, Thomas S. (2013). The Jerome Kern Encyclopedia. Lantham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8108-9167-8.

- ^ "IMCDb.org: "Swing Time, 1936": cars, bikes, trucks and other vehicles". www.imcdb.org.

- ^ Croce, p. 112

- ^ a b The Swing of Things: 'Swing Time' Step by Step (DVD). Warner Home Video. 2005.

- ^ "The Film Business in the United States and Britain during the 1930s" by John Sedgwick and Michael Pokorny, The Economic History ReviewNew Series, Vol. 58, No. 1 (Feb., 2005), pp.97

- ^ "Swing Time (1936)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ "Swing Time Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c Billman, Larry (1997). Fred Astaire – A Bio-bibliography. Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 93. ISBN 0-313-29010-5.

- ^ Never Gonna Dance on the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Charles, Ron (9 November 2016). "'Swing Time': Zadie Smith's sweeping novel about friendship, race and class". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

Bibliography

- Croce, Arlene (1972). The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book. London: W.H. Allen. ISBN 0-491-00159-2.

- Green, Stanley (1999) Hollywood Musicals Year by Year (2nd ed.), pub. Hal Leonard Corporation ISBN 0-634-00765-3 pages 60–61

- Mueller, John (1986). Astaire Dancing – The Musical Films. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-11749-6.

External links

[edit]- Swing Time at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Swing Time at IMDb

- Swing Time at AllMovie

- Swing Time at the TCM Movie Database

- Swing Time at Rotten Tomatoes

- Swing Time: Heaven Can’t Wait an essay by Imogen Sara Smith at the Criterion Collection

- 1936 films

- 1936 musical comedy films

- American black-and-white films

- American dance films

- American musical comedy films

- Blackface minstrel shows and films

- Films directed by George Stevens

- Films produced by Pandro S. Berman

- Films set in New York City

- Films adapted into plays

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- RKO Pictures films

- United States National Film Registry films

- 1930s dance films

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s American films

- English-language musical comedy films