Black Twitter

Black Twitter is an internet community largely consisting of the Black diaspora of users in the United States and other nations on Twitter, focused on issues of interest to the black community.[1][2][3][4] Feminista Jones described it in Salon as "a collective of active, primarily African-American Twitter users who have created a virtual community proving adept at bringing about a wide range of sociopolitical changes."[5] A similar Black Twitter community arose in South Africa in the early 2010s.[6]

User base

[edit]According to a 2013 report by the Pew Research Center, 28 percent of African Americans who had used the Internet, also used Twitter, compared to 20 percent of online white, non-Hispanic Americans.[7] By 2018, this gap had shrunk, with 26 percent of all African American adults using Twitter, compared to 24 percent of white adults and 20 percent of Hispanic adults.[8] In addition, in 2013, 11 percent of African-American Twitter users said they used Twitter at least once a day, compared to 3 percent of white users.[5] BlackTwitter.com was launched as a news aggregator reflective of black culture in 2020.[citation needed]

User and social media researcher André Brock of the University of Iowa dates the first published comments on Black Twitter usage to a 2008 piece by blogger Anil Dash, and a 2009 article by Chris Wilson in The Root describing the viral success of Twitter memes such as #YouKnowYoureBlackWhen and #YouKnowYoureFromQueens that were primarily aimed at Black Twitter users. Brock cites the first reference to a Black Twitter community—as "Late Night Black People Twitter" and "Black People Twitter"—in the November 2009 article "What Were Black People Talking About on Twitter Last Night?" by Choire Sicha, co-founder of current-affairs website The Awl. Sicha described it as "huge, organic and … seemingly seriously nocturnal"—in fact, active around the clock.[9]

Kyra Gaunt, an early adopter who participated in Black Twitter, who also became a social media researcher, shared reactions to black users at the first 140 Characters Conference (#140Conf) that took place on November 17, 2009, at the O2 Indigo in London.[10][11] Her slide deck offered examples of racist reactions to the topic #ThatsAfrican that started trending in July 2008. She and other users claimed the trending topic was censored by the platform.[12] She and other Black Twitter users began blogging and micro-blogging about Black Twitter identity.[13][14] The blogging led to buzz-worthy media appearances about Twitter.[15] Social media researcher Sarah Florini prefers to discuss the interactions among this community of users as an "enclave."[16]

Reciprocity and community

[edit]

An August 2010 article by Farhad Manjoo in Slate, "How Black People Use Twitter," brought the community to wider attention.[1] Manjoo wrote that young black people appeared to use Twitter in a particular way: "They form tighter clusters on the network—they follow one another more readily, they retweet each other more often, and more of their posts are @-replies—posts directed at other users."[18] Manjoo cited Brendan Meeder of Carnegie Mellon University, who argued that the high level of reciprocity between the many users who initiate hashtags (or "blacktags") leads to a high-density, influential network.[18]

A 2014 dissertation by Meredith Clark explains that users on Black Twitter began to use hashtags as a way to attract members of society with similar ideals to a single conversation in order to interact with each other and feel as though they are engaged in a “safe space”. Clark characterizes the use of Black Twitter as critically important to the group, as the conversation helps “cement the hashtag as a cultural artifact recognizable in the minds of both Black Twitter participants and individuals with no knowledge of the initial discussion”. She stated that hashtags have transitioned from serving as a method of setting up a conversation between separate parties to an underlying reason behind how users outside Black Twitter learn about the thoughts and feelings of African Americans in the present world.[19]

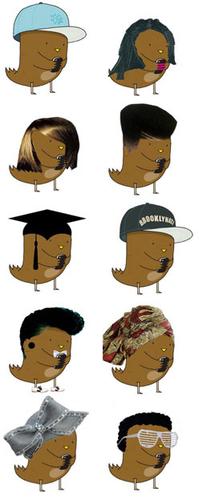

Manjoo's article in Slate drew criticism from American and Africana studies scholar Kimberly C. Ellis. She concluded that large parts of the article had generalized too much, and published a response to it titled "Why 'They' Don't Understand What Black People Do On Twitter." Pointing out the diversity of black people on Twitter, she said, "[I]t's clear that not only Slate but the rest of mainstream America has no real idea who Black people are, no real clue about our humanity, in general [...]. For us, Twitter is an electronic medium that allows enough flexibility for uninhibited and fabricated creativity while exhibiting more of the strengths of social media that allow us to build community. [...] Actually, we talk to each other AND we broadcast a message to the world, hence the popularity of the Trending Topics and Twitter usage, yes?" Ellis said that the most appropriate response she had seen to the Slate article was that by Twitter user @InnyVinny, who made the point that "black people are not a monolith" and then presented a wide array of brown Twitter bird drawings on her blog site to express the diverse range of Black Twitter users; the #browntwitterbird hashtag immediately went viral, as users adopted or suggested new Twitter birds.[17]

According to Shani O. Hilton writing in 2013, the defining characteristic of Black Twitter is that its members "a) are interested in issues of race in the news and pop culture and b) tweet A LOT." She adds that while the community includes thousands of black Twitter users, in fact, "not everyone within Black Twitter is black, and not every black person on Twitter is in Black Twitter". She also notes that the viral reach and focus of Black Twitter's hashtags have transformed it from a mere source of entertainment, and object of outside curiosity, to "a cultural force in its own right ... Now, black folks on Twitter aren't just influencing the conversation online, they're creating it."[20]

Apryl Williams and Doris Domoszlai (2013) similarly state, "There is no single identity or set of characteristics that define Black Twitter. Like all cultural groups, Black Twitter is dynamic, containing a variety of viewpoints and identities. We think of Black Twitter as a social construct created by a self-selecting community of users to describe aspects of black American society through their use of the Twitter platform. Not everyone on Black Twitter is black, and not everyone who is black is represented by Black Twitter."[4]

Signifyin'

[edit]Feminista Jones has argued that Black Twitter's historical cultural roots are the spirituals, or work songs, sung by enslaved people in the United States, when finding a universal means of communication was essential to survival and grassroots organization.[5]

Several writers see Black Twitter interaction as a form of signifyin', wordplay involving tropes such as irony and hyperbole. André Brock states that the Black Tweeter is the signifier, while the hashtag is the signifier, sign and signified, "marking ... the concept to be signified, the cultural context within which the tweet should be understood, and the 'call' awaiting a response." He writes: "Tweet-as-signifyin', then, can be understood as a discursive, public performance of Black identity."[1]

Sarah Florini of UW-Madison also interprets Black Twitter within the context of signifyin'. She writes that race is normally "deeply tied to corporeal signifiers"; in the absence of the body, black users display their racial identities through wordplay and other languages that shows knowledge of black culture. Black Twitter has become an important platform for this performance.[21]

Florini notes that the specific construction of Twitter contributes to African Americans' ability to signify on Black Twitter. She contends that "Twitter’s architecture creates participant structures that accommodate the crucial function of the audience during signifyin’". By seeing each other's replies and retweets, the user base can jointly partake in an extended dialogue where each person tries to participate in the signifyin’. In addition, Florini adds that "Twitter mimics another key aspect of how signifyin’ games are traditionally played—speed". Specifically, the retweets and replies are able to be sent so quickly that it replaces the need for the audience members to interact in person.[21]

In addition the practices of signifying create a signal that one is entering a communicative collective space rather than functioning as an individual. Tweets become part of Black Twitter by responding to the calls in the tag. Hashtags embody a performance of blackness through the transmission of racial knowledge into wordplay. Sarah Florini in particular focuses on how an active self-identification of blackness rejects notions of a post-racial society by disrupting the narratives of a color-blind society. This rejection of a post-racial society gets tied into the collective practices of performance by turning narratives such as the Republican National Committee's declaration of Rosa Parks ending racism[22] into a moment of critique and ridicule under the guise of a game. Moments, where the performance of blackness meets social critique, allow for the spaces of activism to be created. The Republican Party later rescinded its statement to acknowledge that racism was not over.[23]

Manjoo referred to the hashtags the black community uses as "blacktags," citing Baratunde Thurston, then of The Onion, who argued that blacktags are a version of the dozens.[18] Also an example of signifyin', this is a game popular with African Americans in which participants outdo each other by throwing insults back and forth ("Yo momma so bowlegged, she look like a bite out of a donut," "Yo momma sent her picture to the lonely hearts club, but they sent it back and said, 'We ain't that lonely!'").[24] According to Thurston, the brevity of tweets and the instant feedback mean Twitter fits well into the African tradition of call and response.[18]

Black Twitter humor

[edit]Humor as a form of social commentary

Many scholars have highlighted how Black Twitter offers a platform for users to share humorous, yet insightful messages.[21][25]

More recently, Black Twitter spotlighted the "BBQing While Black", incident during which a white woman called police officers on a black family barbecuing in the park. Oakland police arrived; no one was arrested.[26]

When speaking on CNN about her dissent towards former President Donald Trump, CNN commentator Angela Rye stated "[she] will never claim Trump as her bigot president."[27]

Black Twitter and image repair

[edit]In their 2018 book, Race, Gender & Image Repair Case Studies in the Early 21st Century, Mia Moody-Ramirez and Hazel Cole explored how Black Twitter has been used to repair the image of individuals and corporations using William Benoit's typology of image repair.[26] The popularity of #NiggerNavy provides an example of how social media users used Twitter to call out social injustices.[26] Black Twitter reacted in January 2017 when Yahoo Finance misspelled the word "bigger" with an "n" instead of a "b", in a Twitter link to a story on President-elect Donald Trump's plans to enlarge America's navy, thus unintentionally changing what was meant as a "bigger navy" into a "nigger navy". This is a notable example of an "atomic typo" where a typo is undetected by spell checkers because the typo happens to be a correctly spelled word. The tweet containing a racial slur gained more than 1,000 retweets before being deleted, almost one hour after it was shared.[28] Yahoo Finance published an apology shortly after, saying it was a "mistake". It was too late. Black Twitter turned #NiggerNavy into a joke for many Twitter users.[29]

Black women's experience on Black Twitter

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (June 2022) |

Black Twitter is an intersectional space, as Black people have intersecting identities that impact how they engage in spaces. As research shows that college-aged women use social media more than college-aged men, Black college-aged women also use social media more than Black-college aged men.[30] Digital spaces like Twitter have been important spaces for students to resist white supremacy. Dr. Marc Lamont Hill has positioned that, Black Twitter. "Is a digital [space] that enable[s] critical pedagogy, political organizing, and both symbolic and material forms of resistance to anti-Black state violence within the United States".[31] It was also mentioned by former CEO Jack Dorsey that Black Twitter is "such a powerful force".[32] Although Black Twitter is used to unite black people in the fight against white supremacy, it is also a space where Black women face disproportionate abuse. A study performed by Amnesty International shows that Black women are the most abused group on the platform.[33] The study concludes that Black women are 84 percent more likely to be targeted than their white counterparts and that they, along with Latinx women, are faced with more abuse on the platform than any other demographic.[33] Twitter’s acquisition by Elon Musk's has led to the Black community fear that blocked accounts used for harassment, abuse, misinformation and violence may be allowed back on the platform due to Musk's differing viewpoints on free speech, stating that he will be "very reluctant to delete things".[32]

With Black women spending a lot of time on social media, their resistance to white supremacy and creating counter-narratives can be seen through hashtags developed like #BlackGirlMagic, #BlackGirlsMatter, etc. " Social media has become a crucial space for discussing, dismantling, and organizing against anti-Black racism for young Black women."[30]

Influence

[edit]

Having been the topic of a 2012 SXSW Interactive panel led by Kimberly Ellis,[34][35] Black Twitter came to wider public attention in July 2013, when it was credited with having stopped a book deal between a Seattle literary agent and one of the jurors in the trial of George Zimmerman. Zimmerman – who had only been arrested and charged after a large-scale social media campaign including petitions circulated on Twitter that attracted millions of signatures[5][36] – was controversially acquitted that month of charges stemming from the February 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin, a black teenager in Florida.[37] Black Twitter's swift response to the juror's proposed book, spearheaded by Twitter user Genie Lauren, who launched a change.org petition, resulted in coverage on CNN.[20][38]

The community was also involved in June 2013 in protesting to companies selling products by Paula Deen, the celebrity chef, after she was accused of racism, reportedly resulting in the loss of millions of dollars' worth of business.[5] A #paulasbestdishes hashtag game started by writer and humorist Tracy Clayton went viral.[20][39]

In August 2013, outrage on Black Twitter over a Harriet Tubman "sex parody" video Russell Simmons had posted on his Def Comedy Jam website persuaded him to remove the video; he apologized for his error in judgment.[40][41][42]

Another example of Black Twitter's influence occurred in May 2018 after Ambien maker Sanofi Aventis responded to Roseanne Barr, who blamed their sedative for the racist tweet she posted, which resulted in the cancellation of her TV show, Roseanne.[43][44] Barr explained that she was "ambien tweeting" when she compared former Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett to the "spawn" of "Muslim brotherhood & Planet of the Apes."[45] Sanofi responded: "People of all races, religions and nationalities work at Sanofi every day to improve the lives of people around the world. While all pharmaceutical treatments have side effects, racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication."[46] In response to Twitter chatter and criticism, Barr was killed off in Roseanne via an opioid overdose. The show was renamed The Conners.[47]

Demonstrating the continued influence of Black Twitter, a 2019 SXSW Education panel, organized by Kennetta Piper, was selected to address the topic, "We Tried to Tell Y’all: Black Twitter as a Source!" Panelists included Meredith Clark, Feminista Jones, Mia Moody-Ramirez and L. Joy Williams.[48]

In 2022, Black Twitter was credited with prompting national media coverage of the killing of Shanquella Robinson, a young American woman who mysteriously died in Mexico.[49]

#SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen

[edit]The #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen hashtag was created by black feminist blogger/author Mikki Kendall in response to the Twitter comments of male feminist Hugo Schwyzer, a critique of mainstream feminism as catering to the needs of white women, while the concerns of black feminists are pushed to the side.[40][50] The hashtag and subsequent conversations have been part of Black Twitter culture. In Kendall's own words: "#SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen started in a moment of frustration. [...] When I launched the hashtag #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen, I thought it would largely be a discussion between people impacted by the latest bout of problematic behavior from mainstream white feminists. It was intended to be Twitter shorthand for how often feminists of color are told that the racism they feel they experience 'isn't a feminist issue'. The first few tweets reflect the deeply personal impact of such a long-running structural issue."[51]

#IfTheyGunnedMeDown

[edit]After Ferguson, Missouri police officer Darren Wilson fatally shot unarmed resident Michael Brown, an attorney from Jackson, Mississippi named CJ Lawrence tweeted a photo of himself speaking at his commencement at Tougaloo College with former President Bill Clinton laughing in the background and a second photo of himself holding a bottle of Hennessy and a microphone. Lawrence posed the question, "If They Gunned me down which photo would the media use?" The hashtag became the number one trending topic in the world overnight and was ultimately named the most influential hashtag of 2014 by Time magazine. This was a direct criticism of the way Black victims of police violence were portrayed in media, with the assassination of their characters as a result of the choices of images used to depict them. #IfTheyGunnedMeDown spread virally in the course of worldwide social media attention paid to the Ferguson crisis. The hashtag was posted several thousand times in the weeks following Lawrence's initial use of it. #IfTheyGunnedMeDown is now taught in elementary classrooms and in universities around the world.[citation needed] Lawrence, the creator, still lectures on #IfTheyGunnedMeDown and has since established his own media company, Black With No Chaser, to continue the mission of making sure that Black people control their narratives.[52]

#MigosSaid

[edit]The call and response aspects of a game where users work to outdo the other are exemplified in the creation of the blacktag #MigosSaid. Black Twitter engaged in a public display of using oral traditions to critique the hierarchy of pop culture. The movement stemmed from an initial tweet on June 22, 2014, when @Pipe_Tyson tweeted, "Migos best music group since the Beatles." This sparked an online joke where users began to use the hashtag #MigosSaid to examine lyrics of the popular rap group. While the game could widely be seen as a joke it also embodied a critique of popular representations of black artists. The hashtag made in fun was used to offer a counter argument to the view the Beatles and other white popular music figures are more culturally relevant than their black counterparts.[53]

#BlackLivesMatter

[edit]

The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag was created in 2013 by activists Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. They felt that African Americans received unequal treatment from law enforcement. Alicia Garza describes the hashtag as follows: "Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression."[54]

#OscarsSoWhite

[edit]The #OscarsSoWhite hashtag was originally created in 2015 in response to the 87th Academy Awards' lack of diversity amongst the nominees in major categories. The hashtag was used again when the nominations were announced for the 88th Academy Awards the following year. April Reign, activist and former attorney, who is credited with starting the hashtag, tweeted, "It's actually worse than last year.[55] Best Documentary and Best Original Screenplay. That's it. #OscarsSoWhite." In addition, she mentions that none of the African-American cast of Straight Outta Compton were recognized, while the Caucasian screenwriter received nominations.[56]

#SayHerName

[edit]The #SayHerName hashtag was created in February 2015 as part of a gender-inclusive racial justice movement. The movement campaigns for black women in the United States against anti-Black violence and police violence. Gender-specific ways black women are affected by police brutality and anti-Black violence are highlighted in this movement, including the specific impact black queer women and black trans women encounter. The hashtag gained more popularity and the movement gained more momentum following Sandra Bland's death in police custody in July 2015. This hashtag is commonly used with #BlackLivesMatter, reinforcing the intersectionality of the movement.[57][58]

#IfIDieInPoliceCustody

[edit]#IfIDieInPoliceCustody is another hashtag that started trending after Sandra Bland's death. With the growing tweets following the BLM movement police brutality was one of the major themes that struck the black culture. Unsure as to the exact cause of Sandra Bland death the hashtag started as a result.[59] In the tweets, people ask what you would want people to know about you if you died in police custody.[60]

#ICantBreathe

[edit]

The #ICantBreathe hashtag was created after the police killing of Eric Garner and the grand jury's decision to not indict Daniel Pantaleo, the police officer that choked Garner to death, on December 3, 2014. "I can't breathe" were Garner's final words and can be heard in the video footage of the arrest that led to his death. The hashtag trended for days and gained attention beyond Twitter. Basketball players, including LeBron James, wore shirts with the words for warm ups on December 8, 2014.[61][62][63] The hashtag saw resurgence in 2020, following the murder of George Floyd and the protests that followed.[64]

#HandsUpDontShoot

[edit]The #HandsUpDontShoot hashtag was created after the police shooting of Michael Brown and the grand jury's decision to not indict Darren Wilson, the white Ferguson police officer that shot Brown, on November 24, 2015. Witnesses claimed that Brown had his hands up and was surrendering when Wilson fatally shot him. However, this information was deemed not credible in the face of conflicting testimonies and impacted the jury's decision. What made this particular shooting unique, was that Michael Brown's deceased body lied in the ground for four hours. Ferguson residents took to Black Twitter to share images of his body, share the story of Michael Brown being killed with his hands up, and ultimately the failure of the state to value his life. As Dr. Marc Lamont Hill puts it, "These efforts, anchored by the hashtags #MichaelBrown, #Ferguson, and #HandsUpDontShoot, transformed Brown’s death from a local event to an international cause."[65] Hands up, don't shoot is a slogan used by the Black Lives Matter movement and was used during protests after the ruling. The slogan was supported by members of the St. Louis Rams football team, who entered the field during a National Football League game holding their hands up. Using the hashtag on Twitter was a form of showing solidarity with those protesting, show opposition to the decision, and bring attention to police brutality.[66][67][68] The #HandsUpDontShoot hashtag was immediately satirized with #PantsUpDontLoot when peaceful protests turned into riotous looting and firebombing that same evening.[69][70][71]

#BlackGirlMagic/#BlackBoyJoy

[edit]Black Twitter has also been used as a method of praise.[72]

According to Ayanna Harrison, the hashtag #BlackBoyJoy first appeared as a "natural and necessary counterpart to the more established #BlackGirlMagic".[73] The hashtag #BlackBoyJoy appeared following the 2016 Video Music Awards ceremony, after Chance the Rapper tweeted an image of himself on the red carpet using the hashtag.[74]

#StayMadAbby

[edit]In 2015, #StayMadAbby surfaced on Black Twitter as Black students and college graduates rallied against Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia after he made comments about their supposed inability to graduate from universities he labeled "too fast". Scalia's comments came in 2015 during oral arguments for the affirmative action case Fisher v. University of Texas. The suit, filed by one-time prospective student Abigail Fisher, alleged that she was denied admission to the University of Texas at Austin because she was white, and that other, less qualified candidates were admitted because of their race.[75]

The hashtag #StayMadAbby took off with hundreds of Black graduates tweeting photos of themselves clad in caps and gowns, as well as statistics pointedly noting that Black students only account for a small share of the UT Austin student body. The hashtag #BeckyWithTheBadGrades also emerged to spotlight Fisher. The hashtag referred both to Fisher and to a lyric from Beyoncé's song "Sorry".[76]

Reception

[edit]Jonathan Pitts-Wiley, a former writer for The Root, cautioned in 2010 that Black Twitter was just a slice of contemporary African-American culture. "For people who aren't on the inside," he wrote, "it's sort of an inside look at a slice of the black American modes of thought. I want to be particular about that—it's just a slice of it. Unfortunately, it may be a slice that confirms what many people already think they know about black culture."[18]

Daniella Gibbs Leger, wrote in a 2013 HuffPost Black Voices article that "Black Twitter is a real thing. It is often hilarious (as with the Paula Deen recipes hashtag); sometimes that humor comes with a bit of a sting (see any hashtag related to Don Lemon)." Referring to the controversy over the Tubman video, she concluded, "1. Don't mess with Black Twitter because it will come for you. 2. If you're about to post a really offensive joke, take 10 minutes and really think about it. 3. There are some really funny and clever people out there on Twitter. And 4. See number 1."[40]

Criticism

[edit]Labeling

[edit]While Black Twitter is used as a way to communicate within the black community, many people outside of said community and within do not understand the need to label it. In regards to this concern, Meredith Clark, a professor at the University of North Texas who studies black online communities, recalls one user's remarks, "Black Twitter is just Twitter".[77][78]

Intersectionality

[edit]Additional criticism of Black Twitter is the lack of intersectionality.[citation needed] One example is the tweets made after rapper Tyga was pictured with the transgender porn actress Mia Isabella.[clarification needed] Alicia Garza, one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, explained the importance of intersectionality[failed verification] and makes it one of the priorities in the movement. She wrote that many people find certain "charismatic black men" more appealing, which leaves "sisters, queers, trans, and disabled [black] folk [to] take up roles in the background."[79]

South Africa

[edit]Kenichi Serino wrote in 2013 in The Christian Science Monitor that South Africa was experiencing a similar Black Twitter phenomenon, with black discourse on Twitter becoming increasingly influential.[6] In a country that has 11 official languages, Black Twitter users regularly embedded words from isiZulu, isiXhosa, and Sesotho in their tweets.[6] In August 2016 there were approximately 7.7 million South Africans on Twitter – by August 2017, this grew to about eight million users, with 63.8% of South Africans being online.[80] But according to journalism lecturer Unathi Kondile, black people had taken to Twitter as "a free online platform where black voices can assert themselves and their views without editors or publishers deciding if their views matter."[6]

#FeesMustFall

[edit]#FeesMustFall was the most significant hashtag in South African Black Twitter. It started with a student-led protest movement that began in mid October 2015 in response to an increase in fees at South African universities. The protests also called for higher wages for low earning university staff who worked for private contractors such as cleaning services and campus security and for them to be employed directly by universities.[81]

#MenAreTrash

[edit]The #MenAreTrash hashtag was another prominent topic in 2017 on South African Twitter. Black women took to the social media platform to address numerous issues such as rape, patriarchy and domestic violence.[82]

#OperationDudula

[edit]Trending almost on a daily basis in South Africa is the #OperationDudula hashtag. The hashtag is used to rally people against immigration. According to journalist Pumza Fihlani, the movement behind the hashtag was founded by Nhlanhla "Lux" Dlamini, and became prominent in 2021.[83]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c André Brock, "From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation" Archived December 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), December 12, 2012 (hereafter Brock 2012).

- ^ "Black and white: why capitalization matters". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on September 18, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

A website originally registered to the man accused in the Charleston killings, Dylann Roof, capitalizes "White" but not "black", as do many other sites. Publications aimed at blacks often capitalize "Black" but not "white", and there are strong feelings that "Black" should be capitalized. (The home page of the church target in the attack, the Emanuel AME Church, does not capitalize "black".) To start with, let us stipulate that any discussion involving race is fraught: Even thinking there is such a thing as race is controversial, since many anthropologists believe that people cannot be so grouped biologically.

- ^ Tharps, Lori L. (November 18, 2014). "Opinion | The Case for Black With a Capital B". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

In 1926, The New York Times denied his request, as did most other newspapers. In 1929, when the editor for the Encyclopaedia Britannica informed Du Bois that Negro would be lowercased in the article he had submitted for publication, Du Bois quickly wrote a heated retort that called "the use of a small letter for the name of twelve million Americans and two hundred million human beings a personal insult." The editor changed his mind and conceded to the capital N, as did many other mainstream publications including The Atlantic Monthly and, eventually, The New York Times. On March 7, 1930, The Times announced its new policy on the editorial page: "In our Style Book, Negro is now added to the list of words to be capitalized. It is not merely a typographical change, it is an act in recognition of racial respect for those who have been generations in the 'lower case'. "

- ^ a b Apryl Williams and Doris Domoszlai. "#BlackTwitter: a networked cultural identity" Archived September 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Ripple Effect, Harmony Institute, August 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Feminista Jones, "Is Twitter the underground railroad of activism?" Archived November 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Salon, July 17, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kenichi Serino, "#RainbowNation: The rise of South Africa's 'black Twitter'", The Christian Science Monitor, March 7, 2013. Archived June 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Maeve Duggan, Joanna Brenner, "The Demographics of Social Media Users — 2012" Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Pew Internet and American Life Project, Pew Research Center, February 14, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Aaron; Anderson, Monica (March 1, 2018). "Social Media Use in 2018. Appendix A: Detailed table". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Choire Sicha, "What Were Black People Talking About on Twitter Last Night?" Archived June 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Awl, November 11, 2009: "At the risk of getting randomly harshed on by the Internet, I cannot keep quiet about my obsession with Late Night Black People Twitter, an obsession I know some of you other white people share, because it is awesome."

- For Choire Sicha being the first journalist to refer to Black Twitter, see Brock 2012 Archived December 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, p. 533: "The initial coining of 'Black Twitter' is commonly attributed to Choire Sicha's (2009) article, 'What Were Black People Talking About on Twitter Last Night'."

- Chris Wilson, "uknowurblack" Archived May 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Root, September 9, 2009.

- ^ "The Characters « 140 Character Conference". lon.140conf.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ Gaunt, Kyra (December 2, 2009). "London #140 Conf Talk by Kyra Gaunt". SlideShare. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Bunz, Mercedes (November 17, 2009). "#140con: On racism and Twitter". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony. "Black Twitter, Combating the New Jim Crow & the Power of Social Networking". www.newblackmaninexile.net. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Gaunt, Kyra (January 30, 2011). "Black Twitter, Combating the New Jim Crow & the Power of Social Networking – TED Fellows". TED Fellows Blog. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Sydell, Laura (February 3, 2011). "Anti-Social Networks? We're Just As Cliquey Online". All Things Considered, NPR.org. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Florini, Sarah (July 3, 2015). "The Podcast "Chitlin' Circuit": Black Podcasters, Alternative Media, and Audio Enclaves". Journal of Radio and Audio Media. 22 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1080/19376529.2015.1083373. ISSN 1937-6529. S2CID 192455124. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ a b Chase Hoffberger, "The demystification of 'Black Twitter'", The Daily Dot, March 9, 2012. Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Marcia Wade Talbert, "SXSW 2012: The Power of 'Black Twitter'", Black Enterprise, March 14, 2012. Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Kimberly C. Ellis (August 12, 2010). "Why 'They' Don't Understand What Black People Do on Twitter". Dr. Goddess. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012.

- Xeni Jardin, "Brown Twitter Bird: a reaction to 'How Black People Use Twitter'", BoingBoing, August 14, 2010. Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- InnyVinny, "...oh, Slate..." Archived August 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, innyvinny.com, August 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Farhad Manjoo, "How Black People Use Twitter" Archived March 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Slate, August 10, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Meredith (2014). To tweet our own cause: A mixed-methods study of the online phenomenon "Black Twitter". cdr.lib.unc.edu (Thesis). doi:10.17615/7bfs-rp55. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Shani O. Hilton, "The Secret Power Of Black Twitter" Archived November 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, BuzzFeed, July 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c Sarah Florini, "Tweets, Tweeps, and Signifyin’: Communication and Cultural Performance on 'Black Twitter'", Television & New Media, March 7, 2013. Archived October 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ @gop (December 1, 2013). "Today we remember Rosa Parks' bold stand and her role in ending racism" (Tweet). Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (December 2, 2013). "GOP Claims Racism Is Over In Misguided Rosa Parks Tribute". HuffPost. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Cecil Adams, "To African-Americans, what does "signifying" mean?" Archived October 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Straight Dope, September 28, 1984.

- ^ Dates, J. & Mia Moody-Ramirez (2018). From Blackface to Black Twitter: Reflections on Black Humor, Race, Politics & Gender. Peter Lang.

- ^ a b c Moody-Ramirez, M., Cole, H. (2018). Race, Gender & Image Repair Case Studies in the Early 21st Century. Lexington Press.

- ^ Levenson, Eric (February 20, 2017). "'Not My President's Day' protesters rally to oppose Trump". CNN. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ Mezzofiore, G. (2017). "Yahoo accidentally tweeted a racist slur and Twitter is dragging them." Mashable. Retrieved December 17, 2017, from Archived January 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Benoit, W. L. (1995). Accounts, excuses and apologies: A theory of image restoration strategies. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- ^ a b Tanksley, Tiera (2019). Race, Education and #BlackLivesMatter: How Social Media Activism Shapes the Educational Experiences of Black College-Age Women (Thesis). UCLA.

- ^ Hill, Marc Lamont (February 2018). ""Thank You, Black Twitter": State Violence, Digital Counterpublics, and Pedagogies of Resistance". Urban Education. 53 (2): 286–302. doi:10.1177/0042085917747124. ISSN 0042-0859. S2CID 148773395.

- ^ a b "What Happens to #BlackTwitter When Musk Takes Over?". Bloomberg. April 28, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ a b admin (December 19, 2018). "New Study Confirms That Black Women Are Most Abused Group on Twitter". Colorlines. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Kiana Fitzgerald, "Preview – The Bombastic Brilliance of Black Twitter" Archived December 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, SXTX state, February 26, 2012.

- ^ Suzanne Choney, It's a black Twitterverse, white people only live in it Archived February 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Today, March 10, 2012.

- ^ Walter Pacheco, "Trayvon Martin case draws more blacks to Twitter" , Orlando Sentinel, March 28, 2012.

- ^ Jamilah Lemieux, "Justice for Trayvon: Black Twitter Kills Juror B37’s Book", Ebony, July 16, 2013. Archived July 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Don Lemon, "The Influence of Black Twitter", CNN, July 17, 2013.

- ^ Prachi Gupta, "Paula Deen’s racism goes viral with #PaulasBestDishes", Salon, June 19, 2013. Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Daniella Gibbs Leger, "Don't Mess With Black Twitter" Archived September 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, HuffPost, August 22, 2013.

- ^ Service, LAWT News. "Russell Simmons Violates Harriet Tubman". www.lawattstimes.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ "Spike Lee Slams Russell Simmons For Producing Mock Harriet Tubman Sex Tape". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Moody-Ramirez, M. & Cole, H, 2018

- ^ "Ambien maker to Roseanne: Racism is not a side effect of our drug". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Koblin, John (May 29, 2018). "After Racist Tweet, Roseanne Barr's Show Is Canceled by ABC". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ SanofiUS [@sanofius] (May 30, 2018). "People of all races, religions and nationalities work at Sanofi every day to improve the lives of people around the world. While all pharmaceutical treatments have side effects, racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ "'The Conners' reveals how the show kills off Roseanne – and fired Roseanne Barr responds". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "We Tried to Tell Y'all: Black Twitter as a Source". Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "Mexican authorities seek to extradite suspect in North Carolina woman's death". youtube. CBS News.

- ^ "Black Twitter: A virtual community ready to hashtag out a response to cultural issues". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Kendall, Mikki (August 14, 2013). "#SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen: women of color's issue with digital feminism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Vega, Tanzina (August 12, 2014). "Shooting Spurs Hashtag Effort on Stereotypes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ Millard, Drew. "What We Talk About When We Talk About Migos Being Better Than The Beatles." N.p., November 10, 2014. Web. December 13, 2014. Archived August 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement by Alicia Garza". October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Molina-Guzmán, Isabel (2016-10-19). "#OscarsSoWhite: how Stuart Hall explains why nothing changes in Hollywood and everything is changing". Critical Studies in Media Communication. 33 (5): 438–454. doi:10.1080/15295036.2016.1227864. ISSN 1529–5036 Archived August 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ CNN, Brandon Griggs. "Again, #OscarsSoWhite" Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. CNN. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Jiménez, Ileana (November 21, 2016). "#SayHerName Loudly: How Black Girls Are Leading #BlackLivesMatter". Radical Teacher. 106. doi:10.5195/rt.2016.310. ISSN 1941-0832.

- ^ McMurtry-Chubb, Teri A (2016). "#SayHerName #BIackWomensLivesMatter: State Violence in Policing the Black Female Body". Mercer Law Review. 67: 651–705. Archived from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ Carey-Mahoney, Ryan. "Sandra Bland death triggers #IfIDieInPoliceCustody trend". USA TODAY. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Sandra Bland death triggers #IfIDieInPoliceCustody trend" Archived February 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. USA TODAY. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "'I can't breathe.' Eric Garner's last words are 2014's most notable quote, according to a Yale librarian." Archived September 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Washington Post. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Yang, Guobin (August 11, 2016). "Narrative Agency in Hashtag Activism: The Case of #BlackLivesMatter". Media and Communication. 4 (4): 13–17. doi:10.17645/mac.v4i4.692. ISSN 2183-2439.

- ^ Levitt, Jeremy I. (April 5, 2016). "'Fuck Your Breath': Black Men and Youth, State Violence, and Human Rights in the 21st Century". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2759465.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "'I Can't Breathe': Final Words of Black Man Before Being Killed by White Cops Cause Anger on Twitter". News18. May 29, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ Hill, Marc Lamont (January 3, 2018). ""Thank You, Black Twitter": State Violence, Digital Counterpublics, and Pedagogies of Resistance". Urban Education. 53 (2): 286–302. doi:10.1177/0042085917747124. ISSN 0042-0859. S2CID 148773395.

- ^ Frisk, Adam. "#HandsUpDontShoot solidarity rallies continue across U.S." Archived September 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Global News. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Hoyt, Kate Drazner (March 1, 2016). "The affect of the hashtag: #HandsUpDontShoot and the body in peril". Explorations in Media Ecology. 15 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1386/eme.15.1.33_1.

- ^ Jr, Emmett L. Gill (May 18, 2016). ""Hands up, don't shoot" or shut up and play ball? Fan-generated media views of the Ferguson Five". Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 26 (3–4): 400–412. doi:10.1080/10911359.2016.1139990. ISSN 1091–1359 Archived May 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "#PantsUpDontLoot hashtag search". Twitter. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ "Darren Wilson Supporters Crowdfund '#PantsUPDontLOOT' Ferguson Billboard". CBS St. Louis. November 18, 2014. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ "Pants Up, Don't Loot: Controversial Billboard Mocking Ferguson Protesters is Successfully Crowdfunded". November 19, 2014. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Dates, J. & Moody-Ramirez, M. (2018). From Blackface to Black Twitter: Reflections on Black Humor, Race, Politics & Gender. Peter Lang.

- ^ Thomas, Dexter (September 8, 2015). "Why everyone's saying 'Black Girls are Magic'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ Harrison, Ayanna. (2016). "#BlackBoyJoy and Rae Sremmurd: The commoditization of blackness in music." Studlife.com. Retrieved December 17, 2017. Archived January 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Visser, Nick (December 10, 2015). "#StayMadAbby Is Black Students' Perfect Response To Justice Scalia". HuffPost. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Pettit, Emma (June 23, 2016). "Why Twitter Is Calling Abigail Fisher 'Becky With the Bad Grades': A Brief Explainer." The Chronicle. Archived January 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "What people don't get about 'Black Twitter'". Washington Post. Retrieved October 27, 2016. Archived July 3, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Wortham, Jenna. "Black Tweets Matter". Smithsonian. Retrieved October 27, 2016. Archived December 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "When 'Black Twitter' sounds like 'White Twitter'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 27, 2016. Archived August 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How many people use Facebook, Twitter and Instagram in South Africa". Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ "Protests grow over university fee hikes". eNCA. October 19, 2015. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ "The-revolution-will-be-Tweeted". EWN. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ Fihlani, Pumza (March 13, 2022). "Dudula: How South African anger has focused on foreigners". BBC News. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Arceneaux, Michael. "The Miseducation of Black Twitter: Why It's Not What You Think", ComplexTech, December 20, 2012.

- Editorial Staff. "Black Twitter Wikipedia Page Gives The Social Media Force An Official Stamp Of Approval", HuffPost, August 21, 2013.

- Greenfield, Rebecca. "Why Conservatives Love Black Twitter" Archived July 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Wire, July 18, 2013.

- Telusma, Blue. "Study: Black Twitter Matters to the news media (although they don't admit it)", The Grio, February 27, 2018.