Mother

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gestational surrogacy.

A biological mother is the female genetic contributor to the creation of the infant, through sexual intercourse or egg donation. A biological mother may have legal obligations to a child not raised by her, such as an obligation of monetary support. An adoptive mother is a female who has become the child's parent through the legal process of adoption. A putative mother is a female whose biological relationship to a child is alleged but has not been established. A stepmother is a non-biological female parent married to a child's preexisting parent, and may form a family unit but generally does not have the legal rights and responsibilities of a parent in relation to the child.

A father is the male counterpart of a mother. Women who are pregnant may be referred to as expectant mothers or mothers-to-be.[1][2] The process of becoming a mother has been referred to as "matrescence".[3]

The adjective "maternal" refers to a mother and comparatively to "paternal" for a father. The verb "to mother" means to procreate or to sire a child, or to provide care for a child, from which also derives the noun "mothering".[4] Related terms of endearment are mom (mama, mommy), mum (mummy), mumsy, mamacita (ma, mam) and mammy. A female role model that children can look up to is sometimes referred to as a mother-figure.

Types of motherhood

Biological mother

Biological motherhood for humans, as in other mammals, occurs when a pregnant female gestates a fertilized ovum (the "egg"). A female can become pregnant through sexual intercourse after she has begun to ovulate. In well-nourished girls, menarche (the first menstrual period) usually takes place around the age of 12 or 13.[5]

Typically, a fetus develops from the viable zygote, resulting in an embryo. Gestation occurs in the woman's uterus until the fetus (assuming it is carried to term) is sufficiently developed to be born. In humans, gestation is often around 9 months in duration, after which the woman experiences labor and gives birth. This is not always the case, however, as some babies are born prematurely, late, or in the case of stillbirth, do not survive gestation. Usually, once the baby is born, the mother produces milk via the lactation process. The mother's breast milk is the source of antibodies for the infant's immune system, and commonly the sole source of nutrition for newborns before they are able to eat and digest other foods; older infants and toddlers may continue to be breastfed, in combination with other foods, which should be introduced from approximately six months of age.[6]

Childlessness is the state of not having children. Childlessness may have personal, social or political significance. Childlessness may be voluntary childlessness, which occurs by choice, or may be involuntary due to health problems or social circumstances. Motherhood is usually voluntary, but may also be the result of forced pregnancy, such as pregnancy from rape. Unwanted motherhood occurs especially in cultures which practice forced marriage and child marriage.

Non-biological mother

Mother can often apply to a woman other than the biological parent, especially if she fulfills the main social role in raising the child. This is commonly either an adoptive mother or a stepmother (the biologically unrelated partner of a child's father). The term "othermother" or "other mother" is also used in some contexts for women who provide care for a child not biologically their own in addition to the child's primary mother.

Adoption, in various forms, has been practiced throughout history, even predating human civilization.[7] Modern systems of adoption, arising in the 20th century, tend to be governed by comprehensive statutes and regulations. In recent decades, international adoptions have become more and more common.

Adoption in the United States is common and relatively easy from a legal point of view (compared to other Western countries).[8] In 2001, with over 127,000 adoptions, the US accounted for nearly half of the total number of adoptions worldwide.[9]

Surrogate mother

A surrogate mother is a woman who bears a child that came from another woman's fertilized ovum on behalf of a couple unable to give birth to children. Thus the surrogate mother carries and gives birth to a child that she is not the biological mother of. Surrogate motherhood became possible with advances in reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilization.

Not all women who become pregnant via in vitro fertilization are surrogate mothers. Surrogacy involves both a genetic mother, who provides the ovum, and a gestational (or surrogate) mother, who carries the child to term.

Lesbian and bisexual motherhood

The possibility for lesbian and bisexual women in same-sex relationships to become mothers has increased over the past few decades[when?] due to technological developments. Modern lesbian parenting originated with women who were in heterosexual relationships who later identified as lesbian or bisexual, as changing attitudes provided more acceptance for non-heterosexual relationships. Other ways for such women to become mothers is through adopting, foster parenting or in vitro fertilization.[10][11]

Transgender motherhood

Transgender women may have biological children with a partner by utilizing their sperm to fertilize an egg and form an embryo.[12][13] For transgender women, there is currently no accessible way to carry a child. However, research is being done on uterus transplants, which could potentially allow transgender women to carry and give birth to children through Caesarean section. Other types of motherhood include adoption or foster parenting. However, adoption agencies often refuse to work with transgender parents or are reluctant to do so.[14][15]

Social role

The social roles associated with motherhood are variable across time, culture, and social class.[17] Historically, the role of women was confined to some extent to being a mother and wife, with women being expected to dedicate most of their energy to these roles, and to spend most of their time taking care of the home. In many cultures, women received significant help in performing these tasks from older female relatives, such as mothers in law or their own mothers.[18]

Regarding women in the workforce, mothers are said to often follow a "mommy track" rather than being entirely "career women". Mothers may be stay at home mothers or working mothers. In recent decades there has been an increase in stay at home fathers too. Social views on these arrangements vary significantly by culture: in Europe for instance, in German-speaking countries there is a strong tradition of mothers exiting the workforce and being homemakers.[20] Mothers have historically fulfilled the primary role in raising children, but since the late 20th century, the role of the father in child care has been given greater prominence and social acceptance in some Western countries.[21][22] The 20th century also saw more and more women entering paid work. Mothers' rights within the workforce include maternity leave and parental leave.

The social role and experience of motherhood varies greatly depending upon location. Mothers are more likely than fathers to encourage assimilative and communion-enhancing patterns in their children.[23] Mothers are more likely than fathers to acknowledge their children's contributions in conversation.[24][25][26][27] The way mothers speak to their children ("motherese") is better suited to support very young children in their efforts to understand speech (in context of the reference English) than fathers.[24]

Since the 1970s, in vitro fertilization has made pregnancy possible at ages well beyond "natural" limits, generating ethical controversy and forcing significant changes in the social meaning of motherhood.[28][29] This is, however, a position highly biased by Western world locality: outside the Western world, in-vitro fertilization has far less prominence, importance or currency compared to primary, basic healthcare, women's basic health, reducing infant mortality and the prevention of life-threatening diseases such as polio, typhus and malaria.

Traditionally, and still in most parts of the world today, a mother was expected to be a married woman, with birth outside of marriage carrying a strong social stigma. Historically, this stigma not only applied to the mother, but also to her child. This continues to be the case in many parts of the developing world today, but in many Western countries the situation has changed radically, with single motherhood being much more socially acceptable now. For more details on these subjects, see Legitimacy (family law) and single parent.

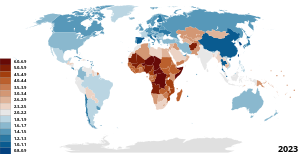

The total fertility rate (TFR), that is, the number of children born per woman, differs greatly from country to country. The TFR in 2013 was estimated to be highest in Niger (7.03 children born per woman) and lowest in Singapore (0.79 children/woman).[30]

In the United States, the TFR was estimated for 2013 at 2.06 births per woman.[30] In 2011, the average age at first birth was 25.6 and 40.7% of births were to unmarried women.[31]

Health

A maternal death is defined by WHO as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes".[32]

About 56% of maternal deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa and another 29% in South Asia.[33]

In 2006, the organization Save the Children has ranked the countries of the world, and found that Scandinavian countries are the safest places to give birth, whereas countries in sub-Saharan Africa are the least safe to give birth.[34] This study argues a mother in the bottom ten ranked countries is over 750 times more likely to die in pregnancy or childbirth, compared to a mother in the top ten ranked countries, and a mother in the bottom ten ranked countries is 28 times more likely to see her child die before reaching their first birthday.

The most recent data suggests that Italy, Sweden and Luxembourg are the safest countries in terms of maternal death and Afghanistan, Central African Republic and Malawi are the most dangerous.[35][36]

Childbirth can be a dangerous process in the absence of effective measures to reduce death. When none of these measure are taken, the maternal death rate has been estimated as being within the order of magnitude of 1,500 deaths per 100,000 births.[37] Modern medicine has greatly alleviated the risk of childbirth. In modern Western countries the current maternal mortality rate is around 10 deaths per 100,000 births.[38]

Religious

Nearly all world religions define tasks or roles for mothers through either religious law or through the glorification of mothers who served in substantial religious events. There are many examples of religious law relating to mothers and women.

Major world religions which have specific religious law or religious texts that comment on mothers include: Christianity,[39] Judaism,[40] and Islam.[41] Some examples of honoring motherhood include the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary as Mother of God and the multiple positive references to active womanhood as a mother in the Book of Proverbs.

Hindu's Mother Goddess and Demeter of ancient Greek pre-Christian belief are also mothers.

Mother-offspring violence

History records many conflicts between mothers and their children. Some even resulted in murder, such as the conflict between Cleopatra III of Egypt and her son Ptolemy X.

In modern cultures, matricide (the killing of one's mother) and filicide (the killing of one's son or daughter) have been studied but remain poorly understood. Psychosis and schizophrenia are common causes of both,[42][43] and young, indigent mothers with a history of domestic abuse are slightly more likely to commit filicide.[43][44] Mothers are more likely to commit filicide than fathers when the child is 8 years old or younger.[45] Matricide is most frequently committed by adult sons.[46]

In the United States in 2012, there were 130 matricides (0.4 per million people) and 383 filicides (1.2 per million), or 1.4 incidents per day.[47]

In art

Throughout history, mothers have been depicted in a variety of art works, including paintings, sculptures and written texts, that have helped define the cultural meaning of 'mother', as well as ideals and taboos of motherhood.

Fourth century grave reliefs on the island of Rhodes depicted mothers with children.[48]

Paintings of mothers with their children have a long tradition in France. In the 18th century, these works embodied the Enlightenment's preoccupation with strong family bonds and the relation between mothers and children.[49]

At the end of the nineteenth century, Mary Cassatt was a painter well known for her portraits of mothers.

American poet, essayist and feminist Adrienne Rich has noted "the disjuncture between motherhood as patriarchal institution and motherhood as complexly and variously lived experience".[50] The vast majority of works depicting motherhood in western art history have been created by artists who are men, with very few having been created by women or mothers themselves, and these often focus on the "institution of motherhood" rather than diverse lived experiences.[51] At the same time, art concerning motherhood has been historically marginalized within the feminist art movement, though this is changing with an increasing number of feminist publications addressing this topic.[52]

The institution of motherhood in western art is often depicted through "the myth of the all-loving, all-forgiving and all-sacrificing mother" and related ideals.[51] Examples include works featuring the Virgin Mary, an archetypal mother and a key historical basis for depictions of mothers in western art from the European Renaissance onwards.[53] Mothers depicted in dominant art works are also primarily white, heterosexual, middle class and young or attractive.[50]

These ideals of motherhood have been challenged by artists with lived experience as mothers. An example in western contemporary art is Mary Kelly's Post-Partum Document. Bypassing typical themes of tenderness or nostalgia, this work documents in extensive detail the challenges, complexities and day-to-day realities of the mother-child relationship.[54] Other artists have addressed similar aspects of motherhood that fall outside dominant ideals, including maternal ambivalence, desire, and the pursuit of self-fulfillment.[52] While the ideal of maternal self-sacrifice and the 'good mother' forms an important part of many works of art relating to the Holocaust, other women's Holocaust and post-Holocaust art has engaged more deeply with mothers' trauma, taboos, and the experiences of second and third-generation Holocaust survivors.[55] For example, works by first-generation survivors of the Holocaust such as Ella Liebermann-Shiber and Shoshana Neuman have depicted mothers abandoning and suffocating their children in an effort to stay alive themselves.

Increasingly diverse representations of motherhood can be found in contemporary works of art. Catherine Opie's self-portrait photographs, including of herself nursing, reference the existing Virgin Mary archetype while subverting its norms around sexuality by centering her identity as a lesbian.[50] Rather than attempting to make her experience of motherhood fit into existing norms, Opie's photographs are "non-traditional and non-apologetic representations".[56]

In her 2020 photography collection, Solana Cain explored the meaning of joy for Black mothers to challenge the lack of images in mainstream media that represent Black motherhood.[57] Renee Cox's Yo Mama series of nude self-portraits challenge historical representations of both the black female body and of maternity and slavery in the US, the latter of which is often characterized by the "extreme passivity and devalued love" typically associated with motherhood.[58]

Synonyms and translations

The proverbial "first word" of an infant often sounds like "ma" or "mama". This strong association of that sound with "mother" has persisted in nearly every language on earth, countering the natural localization of language.

Familiar or colloquial terms for mother in English are:

- Ma(মা), Mata (মাতা), Amma (আম্মা), Ammu (আম্মু) used in Bangladesh, India.

- Aama, Mata used in Nepal

- Mom and mommy are used in the United States, Canada, South Africa, and parts of the West Midlands including Birmingham in the United Kingdom.

- Inay, Nanay, Mama, Ma, Mom, Mommy are used in the Philippines

- Mum and mummy and mama are used in the United Kingdom, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan, Hong Kong and Ireland.

- Ma, mam, and mammy are used in Netherlands, Ireland, the Northern areas of the United Kingdom, and Wales; it is also used in some areas of the United States.

- Mama was imported into Japan from American influence post-World War II, and is a less formal term for mother[59]

In many other languages, similar pronunciations apply:

- Amma (அம்மா) or Thai (தாய்) in Tamil.

- Bi-ma (बिमा) in Bodo.

- Maa, aai, amma, and mata are used in languages of India like Assamese, Bengali, Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu etc.

- Mamá, mama, ma, and mami in Spanish

- Mama in Polish, German, Dutch, Russian and Slovak

- Māma (妈妈/媽媽) in Chinese

- Máma in Czech and in Ukrainian

- Maman in French and Persian

- Ma, mama in Indonesian

- Mamaí, mam in Irish

- Mamma in Italian, Icelandic, Latvian and Swedish

- Māman or mādar in Persian

- Mamãe or mãe in Portuguese

- Mā̃ (ਮਾਂ) in Punjabi

- Mõujì in Kashmiri

- Maa(ମା), Bou/Bau(ବୋଉ/ବଉ) in Odia

- Mama in Swahili

- Em (אם) in Hebrew

- A'ma (ܐܡܐ) in Aramaic

- Má or mẹ in Vietnamese

- Mam in Welsh

- Eomma (엄마, pronounced [ʌmma]) in Korean

- Mma in Tyap

- In many south Asian cultures and the Middle East, the mother is known as amma, oma, ammi or "ummi", or variations thereof. Many times, these terms denote affection or a maternal role in a child's life.

Etymology

The modern English word is from Middle English moder, from Old English mōdor, from Proto-Germanic *mōdēr (cf. East Frisian muur, Dutch moeder, German Mutter), from Proto-Indo-European *méh₂tēr (cf. Irish máthair, Tocharian A mācar, B mācer, Lithuanian mótė). Other cognates include Latin māter, Greek μήτηρ, Common Slavic *mati (thence Russian мать (mat')), Persian مادر (madar), and Sanskrit मातृ (mātṛ).

Notable mothers in mythology

Zoology

In zoology, particularly in mammals, a mother fills many similar biological functions as a human mother.

Mammals

Many other mammal mothers also have numerous commonalities with humans.

Primates

The behavior and role of mothers in non-human species is most similar in species most closely related to humans. This means great apes are most similar, then the broader superfamily of all apes, then all primates.

See also

- Father

- Advanced maternal age

- Attachment parenting

- Baby planner

- Blessed Virgin Mary

- Breastfeeding

- Jungian archetypes

- Lactation

- Maternal bond

- Maternity package

- Matriarch

- Matricide

- Matrilocal residence

- Mother goddess

- Mother insult

- Motherhood penalty

- Mother's Day

- Mothers' rights

- Nuclear family

- Oedipus complex

- Othermother

- Parenting

- Single-parent

References

- ^ "definition of mother from Oxford Dictionaries Online". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Define Mother at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ^ Sacks, Alexandra (8 May 2017). "The Birth of a Mother". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "Definition of MOTHER". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2022-04-16. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ Mishra, Gita D.; Cooper, Rachel; Tom, Sarah E.; Kuh, Diana (2009). "Early Life Circumstances and Their Impact on Menarche and Menopause". Medscape. 5(2). Women's Health. pp. 175–190. Archived from the original on 2009-06-06. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ^ "Your baby's first solid foods". nhs.uk. 2017-12-21. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- ^ Peter Conn (28 January 2013). Adoption: A Brief Social and Cultural History. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 25–64. ISBN 978-1-137-33390-2.

- ^ Jardine, Cassandra (31 Oct 2007). "Why adoption is so easy in America". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11.

- ^ "Child Adoption : Trends and Policies" (PDF). Un.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ "Lesbian parenting: issues, strengths and challenges". Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ Mezey, Nancy J (2008). New Choices, New Families: How Lesbians Decide about Motherhood. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9000-0.

- ^ Halim, Shakera (2019-08-05). "Study shows sperm production for transgender women could still be possible". Health Europa. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ "Reproductive Options for Transgender Individuals". Yale Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ Kinkler, Lori A.; Goldberg, Abbie E. (2011-10-01). "Working With What We've Got: Perceptions of Barriers and Supports Among Small-Metropolitan Same-Sex Adopting Couples". Family Relations. 60 (4): 387–403. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00654.x. ISSN 0197-6664. PMC 3176589. PMID 21949461.

- ^ Montero, Darrel (2014-05-20). "Attitudes Toward Same-Gender Adoption and Parenting: An Analysis of Surveys from 16 Countries". Advances in Social Work. 15 (2): 444–459. doi:10.18060/16139. ISSN 2331-4125. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ Arendell, Terry (2000). "Conceiving and Investigating Motherhood: The Decade's Scholarship". Journal of Marriage and Family. 62 (4): 1192–1207. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01192.x.

- ^ "The Changing Role of Women in North American Mammalogy" (PDF). Biology.unm.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ Website list Archived 2011-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Has childlessness peaked in Europe?" (PDF). Ined.fr. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ [1] Archived August 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ucgstp.org". Ucgstp.org. Archived from the original on 2008-02-25. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ Ann M. Berghout Austin1 and T.J. Braeger2 (1990-10-01). "Gendered differences in parents' encouragement of sibling interaction: implications for the construction of a personal premise system". Fla.sagepub.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-04. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Fathers' speech to their children: perfect pitch or tin ear?". Thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Hladik, E.; Edwards, H. (1984). "A comparison of mother-father speech in the naturalistic home environment". Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 13: 321–332. doi:10.1007/bf01068149. S2CID 144226238.

- ^ Leaper, C.; Anderson, K.; Sanders, P. (1998). "Moderators of gender effects on parents' talk to their children: A meta-analysis". Developmental Psychology. 34 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.3. PMID 9471001.

- ^ Mannle, S.; Tomasello, M. (1987). "Fathers, siblings, and the bridge hypothesis". In Nelson, K. E.; vanKleeck, A. (eds.). Children's language. Vol. 6. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. pp. 23–42.

- ^ "Motherhood: Is It Ever Too Late? | Jacob M. Appel". Huffingtonpost.com. 2009-08-15. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ "Getting Pregnant After 50: Risks, Rewards". Huffingtonpost.com. 2009-08-17. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ^ a b "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ^ "FastStats". cdc.gov. 20 October 2021. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "WHO - Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births)". who.int. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013.

- ^ "Over 99 percent of maternal deaths occur in developing countries". worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- ^ [2] Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kevin Spak (14 April 2010). "Safest Place to Give Birth? Italy". Newser. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Rogers, Simon (2010-04-13). "Maternal mortality: how many women die in childbirth in your country?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2016-12-15.

- ^ Van Lerberghe W, De Brouwere V. Of blind alleys and things that have worked: history's lessons on reducing maternal mortality. In: De Brouwere V, Van Lerberghe W, eds. Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. Antwerp, ITG Press, 2001 (Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy, 17:7–33). "Where nothing effective is done to avert maternal death, "natural" mortality is probably of the order of magnitude of 1,500/100,000."

- ^ ibid, p10

- ^ "What The Bible Says About Mother". Mothers Day World. Archived from the original on 2008-12-19. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Katz, Lisa. "Religious Obligations of Jewish women". About.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ 'Ali Al-Hashimi, Muhammad. The Ideal Muslimah: The True Islâmic Personality of the Muslim Woman as Defined in the Qur'ân and Sunnah. Wisdom Enrichment Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on 2002-03-02. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Bourget, Dominique; Gagné, Pierre; Labelle, Mary-Eve (September 2007). "Parricide: A Comparative Study of Matricide Versus Patricide". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 35 (3): 306–312. PMID 17872550. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b West, Sara G. (Feb 2007). "An Overview of Filicide". Psychiatry. 4 (2): 48–57. PMC 2922347. PMID 20805899.

- ^ Friedman, SH; Horwitz, SM; Resnick, PJ (Sep 2005). "Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (9): 1578–87. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1578. PMID 16135615.

- ^ Greenfeld, Lawrence A., Snell, Tracy L. (1999-02-12, updated 2000-03-10). "Women Offenders". NCJ 175688. US Department of Justice

- ^ Heide, KM (Mar 2013). "Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of U.S. arrest data". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 31 (2): 301–14. doi:10.1002/bsl.2056. PMID 23558726.

- ^ "Crime in the United States: Murder Circumstances by Relationship, 2012". U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society, p. 234, at Google Books

- ^ Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-century France, p. 87, at Google Books

- ^ a b c Heath, Joanne (December 2013). "Negotiating the Maternal: Motherhood, Feminism, and Art". Art Journal. 72 (4): 84–86. doi:10.1080/00043249.2013.10792867. ISSN 0004-3249. S2CID 143550487.

- ^ a b Epp Buller, Rachel (2012). "Introduction". In Epp Buller, Rachel (ed.). Reconciling Art and Mothering. Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-4094-2613-4.

- ^ a b Chernick, Myrel; Klein, Jennie (2011). "Introduction". In Chernick, Myrel; Klein, Jennie (eds.). The M Word: Real Mothers in Contemporary Art. Bradford, Canada: Demeter Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0-9866671-2-1.

- ^ Thurer, Shari (1995). The myths of motherhood : how culture reinvents the good mother. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-024683-5. OCLC 780801259.

- ^ "Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document (article)". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

- ^ Mor Presiado (2018). "The Expansion and Destruction of the Symbol of the Victimized and Self-Sacrificing Mother in Women's Holocaust Art". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (33): 177. doi:10.2979/nashim.33.1.09. ISSN 0793-8934. S2CID 165961732.

- ^ Barnett, Erin (2012). "Lesbian, Pervert, Mother: Catherine Opie's Photographic Transgressions". In Epp Buller, Rachel (ed.). Reconciling Art and Mothering. Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 85–93. ISBN 978-1-4094-2613-4.

- ^ Quammie, Bee (May 5, 2021). "The tenderness and tenacity of Black motherhood". Maclean's. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved Mar 3, 2022.

- ^ Liss, Andrea (2012). "Making the Black Maternal Visible: Renee Cox's Family Portraits". In Epp Buller, Rachel (ed.). Reconciling Art and Mothering. Burlington, VT, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 71–84. ISBN 978-1-4094-2613-4.

- ^ Shoji, Kaori (2004-10-28). "For Japanese, family names are the worst growing pains". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2022-06-09. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

Further reading

- Atkinson, Clarissa W. The Oldest Vocation: Christian Motherhood in the Medieval West (Cornell University Press, 2019).

- Cowling, Camillia, et al. "Mothering slaves: comparative perspectives on motherhood, childlessness, and the care of children in Atlantic slave societies." Slavery & Abolition 38#2 (2017): 223-231. online Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Du, Yue. "Concubinage and Motherhood in Qing China (1644–1911) Ritual, Law, and Custodial Rights of Property." Journal of Family History 42.2 (2017): 162-183.

- Ezawa, Aya. Single Mothers in Contemporary Japan: Motherhood, Class, and Reproductive Practice (2016) online review Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Feldstein, Ruth. Motherhood in black and white (Cornell UP, 2018) in U.S. history.

- Griffin, Emma. "The Value of Motherhood: Understanding Motherhood from Maternal Absence in Victorian Britain." Past & Present 246.Supplement_15 (2020): 167-185.

- Healy-Clancy, Meghan. "The Family Politics of the Federation of South African Women: A History of Public Motherhood in Women's Antiracist Activism" Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 42.4 (2017): 843-866 online Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer. Mother nature: maternal instincts and how they shape the human species.

- Knight, R. J. "Mistresses, motherhood, and maternal exploitation in the Antebellum South." Women's History Review 27.6 (2018): 990-1005 in USA.

- Lerner, Giovanna Faleschini, and D'Amelio Maria Elena, eds. Italian Motherhood on Screen (Springer, 2017).

- McCarthy, Helen. Double Lives: A History of Working Motherhood (Bloomsbury, 2020), focus on UK

- Manne, Anne. Motherhood – How should we care for our children?.

- Massell, Gregory J. The Surrogate Proletariat: Moslem Women and Revolutionary Strategies in Soviet Central Asia, 1919-1929 (Princeton UP, 1974).

- Njoku, C. O., and A. N. Njoku. "Obstetric Fistula: The Agony of Unsafe Motherhood. A Review of Nigeria Experience." Journal of Advances in Medicine and Medical Research (2018): 1-7 online Archived 2021-03-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Portier-Le Cocq, Fabienne, ed. Motherhood in Contemporary International Perspective: Continuity and Change (Routledge, 2019).

- Rahmath, Ayshath Shamah, Raihanah Mohd Mydin, and Ruzy Suliza Hashim. "Archetypal Motherhood and the National Agenda: The Case of the Indian Muslim Women." Space and Culture, India 7.4 (2020): 12-31 online Archived 2021-07-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ramm, Alejandra, and Jasmine Gideon. Motherhood, Social Policies and Women's Activism in Latin America (Springer, 2020).

- Romero, Margarita Sánchez, and Rosa María Cid López, eds. Motherhood and Infancies in the Mediterranean in Antiquity (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2018).

- Rye, Gill, et al., eds. Motherhood in literature and culture: Interdisciplinary perspectives from Europe (Taylor & Francis, 2017).

- Takševa, Tatjana. "Motherhood Studies and Feminist Theory: Elisions and Intersections." Journal of the Motherhood Initiative for Research and Community Involvement 9.1 (2018) online Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- Thornhill, Randy; Gangestad, Steven W. The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality.

- Varma, Mahima. "Adoptive Motherhood in India: State Intervention for Empowerment and Equality." Contemporary Social Sciences 28#3 (2019): 88–101. online Archived 2021-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Vasyagina, Nataliya N., and Aidar M. Kalimullin. "Retrospective analysis of social and cultural meanings of motherhood in Russia." Review of European Studies 7#5 (2015): 61–65.

- Williams, Samantha. Unmarried Motherhood in the Metropolis, 1700–1850 (Springer, 2018) in London. excerpt Archived 2022-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Wood, Elizabeth A. The Baba and the Comrade: Gender and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (Indiana UP, 1997), online review Archived 2021-03-18 at the Wayback Machine