Propane

It has been suggested that parts of this page be moved into Liquefied petroleum gas. (Discuss) (August 2024) |

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propane[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Tricarbane (never recommended[1]) | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1730718 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.753 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E944 (glazing agents, ...) | ||

| 25044 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1978 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[3] | |||

| C3H8 | |||

| Molar mass | 44.097 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | 2.0098 kg/m3 (at 0 °C, 101.3 kPa) | ||

| Melting point | −187.7 °C; −305.8 °F; 85.5 K | ||

| Boiling point | −42.25 to −42.04 °C; −44.05 to −43.67 °F; 230.90 to 231.11 K | ||

| Critical point (T, P) | 370 K (97 °C; 206 °F), 4.23 MPa (41.7 atm) | ||

| 47 mg⋅L−1 (at 0 °C) | |||

| log P | 2.236 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 853.16 kPa (at 21.1 °C (70.0 °F)) | ||

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

15 nmol⋅Pa−1⋅kg−1 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Propanium | ||

| −40.5 × 10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| 0.083 D[2] | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

73.60 J⋅K−1⋅mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−105.2–104.2 kJ⋅mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.2197–2.2187 MJ⋅mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H220 | |||

| P210 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −104 °C (−155 °F; 169 K) | ||

| 470 °C (878 °F; 743 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 2.37–9.5% | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1,000 ppm (1,800 mg/m3)[4] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 1,000 ppm (1,800 mg/m3)[4] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

2,100 ppm[4] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanes

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Propane (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

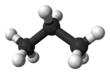

Propane (/ˈproʊpeɪn/) is a three-carbon alkane with the molecular formula C3H8. It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but compressible to a transportable liquid. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum refining, it is often a constituent of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), which is commonly used as a fuel in domestic and industrial applications and in low-emissions public transportation; other constituents of LPG may include propylene, butane, butylene, butadiene, and isobutylene. Discovered in 1857 by the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot, it became commercially available in the US by 1911. Propane has lower volumetric energy density than gasoline or coal, but has higher gravimetric energy density than them and burns more cleanly.[6]

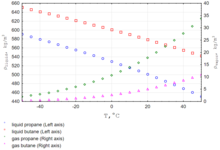

Propane gas has become a popular choice for barbecues and portable stoves because its low −42 °C boiling point makes it vaporise inside pressurised liquid containers (it exists in two phases, vapor above liquid). It retains its ability to vaporise even in cold weather, making it better-suited for outdoor use in cold climates than alternatives with higher boiling points like butane.[7] LPG powers buses, forklifts, automobiles, outboard boat motors, and ice resurfacing machines, and is used for heat and cooking in recreational vehicles and campers. Propane is becoming popular as a replacement refrigerant (R290) for heatpumps also as it offers greater efficiency than the current refrigerants: R410A / R32, higher temperature heat output and less damage to the atmosphere for escaped gasses - at the expense of high gas flammability.[8]

History

[edit]Propane was first synthesized by the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot in 1857 during his researches on hydrogenation. Berthelot made propane by heating propylene dibromide (C3H6Br2) with potassium iodide and water.[9][10]: p. 9, §1.1 [11] Propane was found dissolved in Pennsylvanian light crude oil by Edmund Ronalds in 1864.[12][13] Walter O. Snelling of the U.S. Bureau of Mines highlighted it as a volatile component in gasoline in 1910, which marked the "birth of the propane industry" in the United States.[14] The volatility of these lighter hydrocarbons caused them to be known as "wild" because of the high vapor pressures of unrefined gasoline. On March 31, 1912, The New York Times reported on Snelling's work with liquefied gas, saying "a steel bottle will carry enough gas to light an ordinary home for three weeks".[15]

It was during this time that Snelling—in cooperation with Frank P. Peterson, Chester Kerr, and Arthur Kerr—developed ways to liquefy the LP gases during the refining of gasoline.[14] Together, they established American Gasol Co., the first commercial marketer of propane. Snelling had produced relatively pure propane by 1911, and on March 25, 1913, his method of processing and producing LP gases was issued patent #1,056,845.[14] A separate method of producing LP gas through compression was developed by Frank Peterson and its patent was granted on July 2, 1912.[16]

The 1920s saw increased production of LP gases, with the first year of recorded production totaling 223,000 US gallons (840 m3) in 1922. In 1927, annual marketed LP gas production reached 1 million US gallons (3,800 m3), and by 1935, the annual sales of LP gas had reached 56 million US gallons (210,000 m3). Major industry developments in the 1930s included the introduction of railroad tank car transport, gas odorization, and the construction of local bottle-filling plants. The year 1945 marked the first year that annual LP gas sales reached a billion gallons. By 1947, 62% of all U.S. homes had been equipped with either natural gas or propane for cooking.[14]

In 1950, 1,000 propane-fueled buses were ordered by the Chicago Transit Authority, and by 1958, sales in the U.S. had reached 7 billion US gallons (26,000,000 m3) annually. In 2004, it was reported to be a growing $8-billion to $10-billion industry with over 15 billion US gallons (57,000,000 m3) of propane being used annually in the U.S.[17]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, propane shortages were reported in the United States due to increased demand.[18][19][20]

Etymology

[edit]The "prop-" root found in "propane" and names of other compounds with three-carbon chains was derived from "propionic acid",[21] which in turn was named after the Greek words protos (meaning first) and pion (fat), as it was the "first" member of the series of fatty acids.[22]

Properties and reactions

[edit]

Propane is a colorless, odorless gas. Ethyl mercaptan is added as a safety precaution as an odorant,[23] and is commonly called a "rotten egg" smell.[24] At normal pressure it liquifies below its boiling point at −42 °C and solidifies below its melting point at −187.7 °C. Propane crystallizes in the space group P21/n.[25][26] The low space-filling of 58.5% (at 90 K), due to the bad stacking properties of the molecule, is the reason for the particularly low melting point.

Propane undergoes combustion reactions in a similar fashion to other alkanes. In the presence of excess oxygen, propane burns to form water and carbon dioxide. When insufficient oxygen is present for complete combustion, carbon monoxide, soot (carbon), or both, are formed as well: The complete combustion of propane produces about 50 MJ/kg of heat.[27]

Propane combustion is much cleaner than that of coal or unleaded gasoline. Propane's per-BTU production of CO2 is almost as low as that of natural gas.[28] Propane burns hotter than home heating oil or diesel fuel because of the very high hydrogen content. The presence of C–C bonds, plus the multiple bonds of propylene and butylene, produce organic exhausts besides carbon dioxide and water vapor during typical combustion. These bonds also cause propane to burn with a visible flame.

Energy content

[edit]The enthalpy of combustion of propane gas where all products return to standard state, for example where water returns to its liquid state at standard temperature (known as higher heating value), is (2,219.2 ± 0.5) kJ/mol, or (50.33 ± 0.01) MJ/kg.[27]

The enthalpy of combustion of propane gas where products do not return to standard state, for example where the hot gases including water vapor exit a chimney, (known as lower heating value) is −2043.455 kJ/mol.[29] The lower heat value is the amount of heat available from burning the substance where the combustion products are vented to the atmosphere; for example, the heat from a fireplace when the flue is open.

Density

[edit]The density of propane gas at 25 °C (77 °F) is 1.808 kg/m3, about 1.5× the density of air at the same temperature. The density of liquid propane at 25 °C (77 °F) is 0.493 g/cm3, which is equivalent to 4.11 pounds per U.S. liquid gallon or 493 g/L. Propane expands at 1.5% per 10 °F. Thus, liquid propane has a density of approximately 4.2 pounds per gallon (504 g/L) at 60 °F (15.6 °C).[30]

As the density of propane changes with temperature, this fact must be considered every time when the application is connected with safety or custody transfer operations.[31]

Uses

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

Portable stoves

[edit]Propane is a popular choice for barbecues and portable stoves because the low boiling point of −42 °C (−44 °F) makes it vaporize as soon as it is released from its pressurized container. Therefore, no carburetor or other vaporizing device is required; a simple metering nozzle suffices.

Refrigerant

[edit]Blends of pure, dry "isopropane" [isobutane/propane mixtures of propane (R-290) and isobutane (R-600a)] can be used as the circulating refrigerant in suitably constructed compressor-based refrigeration.[32] Compared to fluorocarbons, propane has a negligible ozone depletion potential and very low global warming potential (having a GWP value of 0.072,[33] 13.9 times lower than the GWP of carbon dioxide) and can serve as a functional replacement for R-12, R-22, R-134a, and other chlorofluorocarbon or hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants in conventional stationary refrigeration and air conditioning systems.[34] Because its global warming effect is far less than current refrigerants, propane was chosen as one of five replacement refrigerants approved by the EPA in 2015, for use in systems specially designed to handle its flammability.[35]

Such substitution is widely prohibited or discouraged in motor vehicle air conditioning systems, on the grounds that using flammable hydrocarbons in systems originally designed to carry non-flammable refrigerant presents a significant risk of fire or explosion.[36]

Vendors and advocates of hydrocarbon refrigerants argue against such bans on the grounds that there have been very few such incidents relative to the number of vehicle air conditioning systems filled with hydrocarbons.[37][38]

Propane is also instrumental in providing off-the-grid refrigeration, as the energy source for a gas absorption refrigerator and is commonly used for camping and recreational vehicles.

It has also been proposed to use propane as a refrigerant in heat pumps.[39]

Domestic and industrial fuel

[edit]

Since it can be transported easily, it is a popular fuel for home heat and backup electrical generation in sparsely populated areas that do not have natural gas pipelines. In June 2023, Stanford researchers found propane combustion emitted detectable and repeatable levels of benzene that in some homes raised indoor benzene concentrations above well-established health benchmarks. The research also shows that gas and propane fuels appear to be the dominant source of benzene produced by cooking.[40]

In rural areas of North America, as well as northern Australia, propane is used to heat livestock facilities, in grain dryers, and other heat-producing appliances. When used for heating or grain drying it is usually stored in a large, permanently-placed cylinder which is refilled by a propane-delivery truck. As of 2014[update], 6.2 million American households use propane as their primary heating fuel.[41]

In North America, local delivery trucks with an average cylinder size of 3,000 US gallons (11 m3), fill up large cylinders that are permanently installed on the property, or other service trucks exchange empty cylinders of propane with filled cylinders. Large tractor-trailer trucks, with an average cylinder size of 10,000 US gallons (38 m3), transport propane from the pipeline or refinery to the local bulk plant. The bobtail tank truck is not unique to the North American market, though the practice is not as common elsewhere, and the vehicles are generally called tankers. In many countries, propane is delivered to end-users via small or medium-sized individual cylinders, while empty cylinders are removed for refilling at a central location.

There are also community propane systems, with a central cylinder feeding individual homes.[42]

Motor fuel

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

In the U.S., over 190,000 on-road vehicles use propane, and over 450,000 forklifts use it for power. It is the third most popular vehicle fuel in the world,[43] behind gasoline and diesel fuel. In other parts of the world, propane used in vehicles is known as autogas. In 2007, approximately 13 million vehicles worldwide use autogas.[43]

The advantage of propane in cars is its liquid state at a moderate pressure. This allows fast refill times, affordable fuel cylinder construction, and price ranges typically just over half that of gasoline. Meanwhile, it is noticeably cleaner (both in handling, and in combustion), results in less engine wear (due to carbon deposits) without diluting engine oil (often extending oil-change intervals), and until recently[when?] was relatively low-cost in North America. The octane rating of propane is relatively high at 110. In the United States the propane fueling infrastructure is the most developed of all alternative vehicle fuels. Many converted vehicles have provisions for topping off from "barbecue bottles". Purpose-built vehicles are often in commercially owned fleets, and have private fueling facilities. A further saving for propane fuel vehicle operators, especially in fleets, is that theft is much more difficult than with gasoline or diesel fuels.

Propane is also used as fuel for small engines, especially those used indoors or in areas with insufficient fresh air and ventilation to carry away the more toxic exhaust of an engine running on gasoline or diesel fuel. More recently,[when?] there have been lawn-care products like string trimmers, lawn mowers and leaf blowers intended for outdoor use, but fueled by propane in order to reduce air pollution.[44]

Many heavy-duty highway trucks use propane as a boost, where it is added through the turbocharger, to mix with diesel fuel droplets. Propane droplets' very high hydrogen content helps the diesel fuel to burn hotter and therefore more completely. This provides more torque, more horsepower, and a cleaner exhaust for the trucks. It is normal for a 7-liter medium-duty diesel truck engine to increase fuel economy by 20 to 33 percent when a propane boost system is used. It is cheaper because propane is much cheaper than diesel fuel. The longer distance a cross-country trucker can travel on a full load of combined diesel and propane fuel means they can maintain federal hours of work rules with two fewer fuel stops in a cross-country trip. Truckers, tractor pulling competitions, and farmers have been using a propane boost system for over forty years[when?] in North America.

Other uses

[edit]- Propane is the primary flammable gas in blowtorches for soldering.

- Propane is used in oxy-fuel welding and cutting. Propane does not burn as hot as acetylene in its inner cone, and so it is rarely used for welding. Propane, however, has a very high number of BTUs per cubic foot in its outer cone, and so with the right torch (injector style) it can make a faster and cleaner cut than acetylene, and is much more useful for heating and bending than acetylene.

- Propane is used as a feedstock for the production of base petrochemicals in steam cracking.

- Propane is the primary fuel for hot-air balloons.

- It is used in semiconductor manufacture to deposit silicon carbide.

- Propane is commonly used in theme parks and in movie production as an inexpensive, high-energy fuel for explosions and other special effects.

- Propane is used as a propellant, relying on the expansion of the gas to fire the projectile. It does not ignite the gas. The use of a liquefied gas gives more shots per cylinder, compared to a compressed gas.

- Propane is also used as a cooking fuel.

- Propane is used as a propellant for many household aerosol sprays, including shaving creams and air fresheners.

- Propane is a promising feedstock for the production of propylene.[citation needed]

- Liquified propane is used in the extraction of animal fats and vegetable oils.[45]

Purity

[edit]The North American standard grade of automotive-use propane is rated HD-5 (Heavy Duty 5%). HD-5 grade has a maximum of 5 percent butane, but propane sold in Europe has a maximum allowable amount of butane of 30 percent, meaning it is not the same fuel as HD-5. The LPG used as auto fuel and cooking gas in Asia and Australia also has very high butane content.

Propylene (also called propene) can be a contaminant of commercial propane. Propane containing too much propene is not suited for most vehicle fuels. HD-5 is a specification that establishes a maximum concentration of 5% propene in propane. Propane and other LP gas specifications are established in ASTM D-1835.[46] All propane fuels include an odorant, almost always ethanethiol, so that the gas can be smelled easily in case of a leak. Propane as HD-5 was originally intended for use as vehicle fuel. HD-5 is currently being used in all propane applications.

Typically in the United States and Canada, LPG is primarily propane (at least 90%), while the rest is mostly ethane, propylene, butane, and odorants including ethyl mercaptan.[47][48] This is the HD-5 standard, (maximum allowable propylene content, and no more than 5% butanes and ethane) defined by the American Society for Testing and Materials by its Standard 1835 for internal combustion engines. Not all products labeled "LPG" conform to this standard, however. In Mexico, for example, gas labeled "LPG" may consist of 60% propane and 40% butane. "The exact proportion of this combination varies by country, depending on international prices, on the availability of components and, especially, on the climatic conditions that favor LPG with higher butane content in warmer regions and propane in cold areas".[49]

Comparison with natural gas

[edit]Propane is bought and stored in a liquid form, LPG. It can easily be stored in a relatively small space.

By comparison, compressed natural gas (CNG) cannot be liquefied by compression at normal temperatures, as these are well above its critical temperature. As a gas, very high pressure is required to store useful quantities. This poses the hazard that, in an accident, just as with any compressed gas cylinder (such as a CO2 cylinder used for a soda concession) a CNG cylinder may burst with great force, or leak rapidly enough to become a self-propelled missile. Therefore, CNG is much less efficient to store than propane, due to the large cylinder volume required. An alternative means of storing natural gas is as a cryogenic liquid in an insulated container as liquefied natural gas (LNG). This form of storage is at low pressure and is around 3.5 times as efficient as storing it as CNG.

Unlike propane, if a spill occurs, CNG will evaporate and dissipate because it is lighter than air.

Propane is much more commonly used to fuel vehicles than is natural gas, because that equipment costs less. Propane requires just 1,220 kilopascals (177 psi) of pressure to keep it liquid at 37.8 °C (100 °F).[50]

Hazards

[edit]Propane is a simple asphyxiant.[51] Unlike natural gas, it is denser than air. It may accumulate in low spaces and near the floor. When abused as an inhalant, it may cause hypoxia (lack of oxygen), pneumonia, cardiac failure or cardiac arrest.[52][53] Propane has low toxicity since it is not readily absorbed and is not biologically active. Commonly stored under pressure at room temperature, propane and its mixtures will flash evaporate at atmospheric pressure and cool well below the freezing point of water. The cold gas, which appears white due to moisture condensing from the air, may cause frostbite.

Propane is denser than air. If a leak in a propane fuel system occurs, the vaporized gas will have a tendency to sink into any enclosed area and thus poses a risk of explosion and fire. The typical scenario is a leaking cylinder stored in a basement; the propane leak drifts across the floor to the pilot light on the furnace or water heater, and results in an explosion or fire. This property makes propane generally unsuitable as a fuel for boats. In 2007, a heavily investigated vapor-related explosion occurred in Ghent, West Virginia, U.S., killing four people and completely destroying the Little General convenience store on Flat Top Road, causing several injuries.[54][55]

Another hazard associated with propane storage and transport is known as a BLEVE or boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion. The Kingman Explosion involved a railroad tank car in Kingman, Arizona, U.S., in 1973 during a propane transfer. The fire and subsequent explosions resulted in twelve fatalities and numerous injuries.[56]

Production

[edit]Propane is produced as a by-product of two other processes, natural gas processing and petroleum refining. The processing of natural gas involves removal of butane, propane, and large amounts of ethane from the raw gas, to prevent condensation of these volatiles in natural gas pipelines. Additionally, oil refineries produce some propane as a by-product of cracking petroleum into gasoline or heating oil.

The supply of propane cannot easily be adjusted to meet increased demand, because of the by-product nature of propane production. About 90% of U.S. propane is domestically produced.[41] The United States imports about 10% of the propane consumed each year, with about 70% of that coming from Canada via pipeline and rail. The remaining 30% of imported propane comes to the United States from other sources via ocean transport.

After it is separated from the crude oil, North American propane is stored in huge salt caverns. Examples of these are Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta; Mont Belvieu, Texas; and Conway, Kansas. These salt caverns[57] can store 80,000,000 barrels (13,000,000 m3) of propane.

Retail cost

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2017) |

United States

[edit]As of October 2013[update], the retail cost of propane was approximately $2.37 per gallon, or roughly $25.95 per 1 million BTUs.[58] This means that filling a 500-gallon propane tank, which is what households that use propane as their main source of energy usually require, cost $948 (80% of 500 gallons or 400 gallons), a 7.5% increase on the 2012–2013 winter season average US price.[59] However, propane costs per gallon change significantly from one state to another: the Energy Information Administration (EIA) quotes a $2.995 per gallon average on the East Coast for October 2013,[60] while the figure for the Midwest was $1.860 for the same period.[61]

As of December 2015[update], the propane retail cost was approximately $1.97 per gallon,[62] which meant filling a 500-gallon propane tank to 80% capacity costed $788, a 16.9% decrease or $160 less from November 2013. Similar regional differences in prices are present with the December 2015 EIA figure for the East Coast at $2.67 per gallon and the Midwest at $1.43 per gallon.[62]

As of August 2018[update], the average US propane retail cost was approximately $2.48 per gallon. The wholesale price of propane in the U.S. always drops in the summer as most homes do not require it for home heating. The wholesale price of propane in the summer of 2018 was between 86 cents to 96 cents per U.S. gallon, based on a truckload or railway car load. The price for home heating was exactly double that price; at 95 cents per gallon wholesale, a home-delivered price was $1.90 per gallon if ordered 500 gallons at a time. Prices in the Midwest are always less than in California. Prices for home delivery always go up near the end of August or the first few days of September when people start ordering their home tanks to be filled.[63]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "General Principles, Rules, and Conventions". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. P-12.1. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

Similarly, the retained names 'ethane', 'propane', and 'butane' were never replaced by systematic names 'dicarbane', 'tricarbane', and 'tetracarbane' as recommended for analogues of silane, 'disilane'; phosphane, 'triphosphane'; and sulfane, 'tetrasulfane'.

- ^ Lide, David R. Jr. (1960). "Microwave Spectrum, Structure, and Dipole Moment of Propane". J. Chem. Phys. 33 (5): 1514–1518. Bibcode:1960JChPh..33.1514L. doi:10.1063/1.1731434.

- ^ Record of Propane in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0524". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "PROPANE – CAMEO Chemicals – NOAA". cameochemicals.noaa.gov. NOAA Office of Response and Restoration, US GOV.

- ^ "Fuels". www.globalfueleconomy.org. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ "The difference between butane and propane". Calor Gas News and Views. Calor Gas Ltd UK.

- ^ "Propane". vasa.org.au. Retrieved 2024-05-11.

- ^ Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences (in French). Vol. 140. Académie des Sciences. 1905.

- ^ Acetylene and Its Polymers : 150+ Years of History, Seth C. Rasmussen, Springer, 2018, ISBN 978-3-319-95489-9, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95489-9.

- ^ "Substitutions inverses", Marcellin Berthelot, pp. 48-58 in Annales de chimie et de physique, 3rd ser., 51, Paris : Victor Masson, 1857.

- ^ Roscoe, H.E.; Schorlemmer, C. (1881). Treatise on Chemistry. Vol. 3. Macmillan. pp. 144–145.

- ^ Watts, H. (1868). Dictionary of Chemistry. Vol. 4. p. 385.

- ^ a b c d National Propane Gas Association. "The History of Propane". Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ "GAS PLANT IN STEEL BOTTLE.; Dr. Snelling's Process Gives Month's Supply in Liquid Form". The New York Times. April 1, 1912. p. 9. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ "The First Fifty Years of LP-Gas: An Industry Chronology" (PDF). LPGA Times. January 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-07., Page 17.

- ^ Propane Education & Research Council. "Fact Sheet – The History of Propane". Archived from the original on February 16, 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ Puente, Victor (7 December 2020). "Propane shortage: An unexpected side effect of the pandemic and restaurant mandates". WKYT. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ^ Lott, Jennifer (14 January 2021). "Southwest Louisiana is experiencing a propane supply shortage". KPLC. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ^ Peguero, Joshua (6 December 2020). "Pandemic is creating an increase in demand for propane, as some homeowners struggle to get some". WBAY. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary entry for propane". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam. 1913. OCLC 800618302. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ NIOSH [2021]. Odor fade in natural gas and propane. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2021-106 (revised 01/2022), https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2021106revised012022external icon.

- ^ "What to do if You Smell Propane Gas".

- ^ "geometry of crystalline propane".

- ^ Boese R, Weiss HC, Blaser D (1999). "The melting point alternation in the short-chain n-alkanes: Single-crystal X-ray analyses of propane at 30 K and of n-butane to n-nonane at 90 K". Angew Chem Int Ed. 38: 988–992. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990401)38:7<988::AID-ANIE988>3.3.CO;2-S.

- ^ a b Propane. NIST Standard Reference Data referring to Pittam, D. A.; Pilcher, G. (1972). "Measurements of heats of combustion by flame calorimetry. Part 8.—Methane, ethane, propane, n-butane and 2-methylpropane". Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 1: Physical Chemistry in Condensed Phases. 68: 2224. doi:10.1039/f19726802224. and Rossini, F.D. (1934). "Calorimetric determination of the heats of combustion of ethane, propane, normal butane, and normal pentane". Bureau of Standards Journal of Research. 12 (6): 735–750. doi:10.6028/jres.012.059.

- ^ United States Energy Information Association. "How much carbon dioxide is produced when different fuels are burned". Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Ҫengel, Yunus A.; Boles, Michael A. (2006). Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach (Fifth ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 925. ISBN 978-0-07-288495-1.

- ^ Razmi, Amir (May 2019). "Propylene Production by Propane Dehydrogenation (PDH)". Engineering: 3.

- ^ Zivenko, Oleksiy (2019). "LPG Accounting Specificity During ITS Storage and Transportation". Measuring Equipment and Metrology. 80 (3): 21–27. doi:10.23939/istcmtm2019.03.021. ISSN 0368-6418. S2CID 211776025.

- ^ Başaran, Anıl (August 10, 2023). "Experimental investigation of R600a as a low GWP substitute to R134a in the closed-loop two-phase thermosyphon of the mini thermoelectric refrigerator". Applied Thermal Engineering. 211. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.118501. S2CID 248206074. Archived from the original on August 11, 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis

- ^ "European Commission on retrofit refrigerants for stationary applications" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 5, 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Koch, Wendy (March 6, 2015). "Why Your Fridge Pollutes and How It's Changing". National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^

- "U.S. EPA hydrocarbon-refrigerants FAQ". Epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2002-12-31. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Compendium of hydrocarbon-refrigerant policy statements, October 2006. vasa.org.au

- "MACS bulletin: hydrocarbon refrigerant usage in vehicles" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Society of Automotive Engineers hydrocarbon refrigerant bulletin". Sae.org. 2005-04-27. Archived from the original on 2005-05-05. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Shade Tree Mechanic on hydrocarbon refrigerants". Shadetreemechanic.com. 2005-04-27. Archived from the original on 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Saskatchewan Labour bulletin on hydrocarbon refrigerants in vehicles". Labour.gov.sk.ca. 2010-06-29. Archived from the original on 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- VASA on refrigerant legality & advisability. vasa.org.au

- "Queensland (Australia) government warning on hydrocarbon refrigerants" (PDF). Energy.qld.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 17, 2008. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 16 October 1997". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. 1997-10-16. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 29 June 2000". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 May 2005. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Everitt, Neil (2023-03-18). "Scientists back propane in heat pumps". Cooling Post. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ^ Kashtan, Yannai S.; Nicholson, Metta; Finnegan, Colin; Ouyang, Zutao; Lebel, Eric D.; Michanowicz, Drew R.; Shonkoff, Seth B. C.; Jackson, Robert B. (June 15, 2023). "Gas and Propane Combustion from Stoves Emits Benzene and Increases Indoor Air Pollution". Environmental Science & Technology. 57 (26): 9653–9663. Bibcode:2023EnST...57.9653K. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c09289. PMC 10324305. PMID 37319002.

- ^ a b Sloan, Michael. "2016 Propane Market Outlook" (PDF). Propane Education and Research Council. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Council, Propane Education & Research. "Community Propane Systems | Propane.com". Propane. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ a b Propane Education & Research Council. "Autogas". PERC. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ "Facts About Propane: America's Exceptional Energy" (PDF). National Propane Gas Association. April 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ Stoye, Dieter (2000). "Solvents". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_437. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ "ASTM D1835 - 16 Standard Specification for Liquefied Petroleum (LP) Gases". www.astm.org.

- ^ Amerigas. "Amerigas Material Safety Data Sheet for Odorized Propane" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ^ Suburban Propane. "Suburban Propane Material Safety Data Sheet for Commercial Odorized Propane" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ^ Mexican Ministry of Energy. "Liquefied Petroleum Gas Market Outlook 2008–2017" (PDF). Mexican Ministry of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ "Propane Vapor Pressure". The Engineering ToolBox. 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ "Propane". The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Retrieved 2016-05-12.

Propane is a simple asphyxiant and does not present an IDLH hazard at concentrations below its lower explosive limit (LEL). The chosen IDLH is based on the LEL of 21,000 ppm rounded down to 20,000 ppm.

- ^ "Inhalants – Facts and Statistics". Greater Dallas Council on Alcohol & Drug Abuse. March 4, 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-04-08.

- ^ "Inhalants". National Inhalant Prevention Coalition. 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Little General Store Propane Explosion". US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. September 25, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (September 25, 2008). "Investigation Report:Little General Store-Propane Explosion (four killed, six injured)" (PDF). Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Disaster Story". Kingman Historic District. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Argonne National Laboratory (1999). "Salt Cavern Information Center". Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ^ US Energy Information Administration (November 12, 2013). "Heating Oil and Propane Prices".

- ^ Propane Deal (November 12, 2013). "Current Propane Prices".

- ^ US Energy Information Administration (November 12, 2013). "East Coast Heating Oil and Propane Prices".

- ^ US Energy Information Administration (November 12, 2013). "Midwest Heating Oil and Propane Prices".

- ^ a b US Energy Information Administration (December 12, 2015). "Residential Propane: Weekly Heating Oil and Propane Prices (October – March)".

- ^ US Energy Information Administration (August 11, 2018). "Residential Propane: Weekly Heating Oil and Propane Prices (October – March)".

External links

[edit]- Canadian Propane Association

- Kaoru Fujimoto; Hiroshi Kaneko; Qianwen Zhang; Qingjie Ge; Xiaohong Li (2007). "Direct synthesis of propane/butane from synthesis gas". In Noronha, F.B.; Schmal, M.; Sousa-Aguiar, E.F. (eds.). Natural Gas Conversion VIII, Proceedings of the 8th Natural Gas Conversion Symposium. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. Vol. 167. Elsevier. pp. 349–354. doi:10.1016/S0167-2991(07)80156-X. ISBN 9780444530783. (syngas)

- International Chemical Safety Card 0319

- National Propane Gas Association (U.S.)

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Propane Education & Research Council (U.S.)

- Propane Properties Explained Descriptive Breakdown of Propane Characteristics

- UKLPG: Propane and Butane in the UK

- US Energy Information Administration

- World LP Gas Association (WLPGA)