PRO (linguistics)

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

In generative linguistics, PRO (called "big PRO", distinct from pro, "small pro" or "little pro") is a pronominal determiner phrase (DP) without phonological content. As such, it is part of the set of empty categories. The null pronoun PRO is postulated in the subject position of non-finite clauses.[1] One property of PRO is that, when it occurs in a non-finite complement clause, it can be bound by the main clause subject ("subject control") or the main clause object ("object control"). The presence of PRO in non-finite clauses lacking overt subjects allows a principled solution for problems relating to binding theory.[1]

Within government and binding theory, the existence and distribution of PRO followed from the PRO theorem, which states that PRO may not be governed.[2] More recent analyses have abandoned the PRO theorem.[3] Instead, PRO is taken to be in complementary distribution with overt subjects because it is the only item that is able to carry null case which is checked for by non-finite tense markers (T), for example the English to in control infinitives.[4]

Motivation for PRO

[edit]There are several independent pieces of linguistic theory which motivate the existence of PRO.[3][5] The following four are reviewed here:

- the extended projection principle

- the theta criterion

- binding theory

- nominal agreement

Extended projection principle

[edit]The extended projection principle (EPP) requires that all clauses have a subject. A consequence of the EPP is that clauses that lack an overt subject must necessarily have an "invisible" or "covert" subject; with non-finite clauses this covert subject is PRO.[5]

Motivation for a PRO subject comes from the grammaticality of sentences such as (1) and (2), where the subject of the infinitival to-clause, though not overtly expressed, is understood to be controlled by an argument of the main clause. In (1a), the subject of control is understood to be the same person that issued the promise, namely John. This is annotated in (1b) by co-indexing John with PRO, which indicates that the PRO subject of [TP to control the situation] co-refers with John. In (2a), the subject of sleep is understood to be the same person that was convinced, namely Bill. This is annotated in(2b) by co-indexing Bill with PRO, which indicates that the PRO subject of [TP to sleep] co-refers with Bill.

(1) a. John promised Bill to control the situation.

b. Johnj promised Bill [CP[TP PROj to control the situation]]

(2) a. John convinced Bill to sleep.

b. John convinced Billk [CP[TP PROk to sleep]]

(adapted from: Koopman, Sportiche and Stabler 2014: 247 (29), 251 (47b))

|

Since the argument that controls PRO in (1a) is the subject, this is called subject control, and PRO is co-indexed with its antecedent John, As shown in (2a), it is also possible to have object control, where the argument that controls PRO is the object of the main clause, and PRO is co-indexed with its antecedent Bill.

In the context of the EPP, the existence of subject and object control follows naturally from the fact that the null pronominal subject PRO can be co-indexed with different DP arguments. While (1a) and (2a) show the surface sentences, (1b) and (2b) show the more abstract structure where PRO serves as the subject of the non-finite clauses, thereby satisfying the EPP-feature of T (realized by infinitival 'to'). The following tree diagrams of examples (1) and (2) show how PRO occupies the subject position of non-finite clauses.

|

|

Theta criterion

[edit]Every verb has theta roles and under the theta criterion every theta role must be present in the structure of the sentence;[5] this means that theta roles must be associated with a syntactic position even when there is no overt argument. Therefore, in the absence of an overt subject, the null category PRO helps to satisfy the theta criterion.[5] For example:

(3) a. John promised Mary to examine the patient.

b. John promised Mary [PRO to examine the patient].

(adapted from: Koopman, Sportiche and Stabler 2014: 247 (31))

|

In example (3), the verb examine is associated with the following lexical entry:

examine: V <DPagent DPtheme>[1]

Accordingly, the verb examine must have a DP (determiner phrase) as an agent and a DP as a theme. However, in (3a), since no overt DP functions as the agent of examine, this should be a violation of the theta criterion.[1] However, the presence of the null PRO subject, as shown (3b),[1] satisfies the theta criterion by having PRO as the DPagent in the sentence and the patient as the DPtheme.[1] The tree diagram (3) represents how PRO satisfies the theta criterion of examine by being the DPagent in the non-finite clause.

Binding theory

[edit]

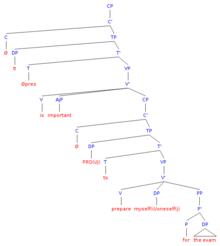

The claim that non-finite clauses have a phonologically null PRO subject is in part motivated by binding theory — in particular, the idea that an anaphor requires a local antecedent to be present. Reflexive pronouns such as myself and oneself require a local antecedent. As shown in (4), PRO can function as an antecedent for reflexives: in (4a) PRO is the antecedent for the reflexive pronoun 'myself', and in (4b) PRO functions as the antecedent for the impersonal reflexive oneself. If the null subject PRO were not present in examples like (4a) and (4b), then non-finite clauses would contain anaphors that lacked a local antecedent, and incorrectly predicting that such sentences to be ungrammatical. The grammaticality of such sentences confirms that the reflexives have an antecedent, which by hypothesis is PRO.[3]

(4) a. It's important [PROi to prepare myselfi properly for the exam]

b. It's important [PROj to prepare oneselfj properly for the exam]

(Radford 2004: 111)

|

Note, however, that PRO itself has no local antecedent in these examples: PRO can share reference with an external referent as in (4a), or have an arbitrary reading as in (4b).

Nominal agreement

[edit]Evidence that non-finite clauses have a phonologically null PRO subject comes from the fact that predicate nominals must agree with the subject of a copular clause.[3] This is illustrated in (5) and (6). Example (5) shows that the number of the predicate nominal must agree with that of the overt subject: in (5a) the singular subject (their son) requires a singular nominal predicate (millionaire); in (5b), the plural subject (his sons) requires a plural nominal predicate (millionaires). The examples in (6) show that the same contrast holds of PRO subjects: if PRO is controlled by a singular antecedent, in (6a) the subject of want, then the predicate nominal must be singular; if PRO is controlled by a plural antecedent, as in (6b), then the predicate nominal must be plural.

(5) a. They want [their son to become a millionaire/*millionaires]

b. He wants [his sons to become *a millionaire/millionaires]

(6) a. He wants [PRO to become a millionaire/*millionaires]

b. They want [PRO to become *a millionaire/millionaires]

(adapted from Radford 2004: 110)

|

The following tree diagrams show how PRO, as the subject of the copular clause, enters into agreement with the nominal predicate introduced by the copular verb become. The application of agreement is automatically explained if PRO is co-indexed with the subject of the main clause, with the predicate nominal simply agreeing with the number features of the argument that controls PRO, just as it would be if an overt subject had been introduced.[3]

|

|

Theoretical status of PRO

[edit]There are two main approaches to PRO:

- work from the 1980s attempts to derive its existence from the PRO theorem

- recent work emphasizes the connection of PRO with weak case

PRO theorem

[edit]The interpretation of PRO may be dependent on another noun phrase; in this respect PRO behaves like an anaphor. But it is also possible for PRO to have arbitrary reference; in this respect, PRO behaves like a pronominal. This is why, in terms of features, PRO may be described as follows:

PRO = [+anaphor, +pronominal]

However, this set of features poses a problem for binding theory, as it imposes contradictory constraints on the distribution of PRO. This is because an anaphor must be bound in its governing category, but a pronominal must be free in its governing category:

an anaphor must be bound in governing category a pronominal must be free in governing category

Chomsky (1981) solves this paradox with the so-called PRO theorem which states that PRO must be ungoverned.

Since PRO cannot be governed it cannot have a governing category, and so is exempt from the binding theory.[2] Under this definition, the features of PRO no longer conflict with the principles of binding theory. However, developments in binding theory since 1981 have presented significant challenges to the PRO theorem.[6] For example, if PRO is ungoverned, then it must not be case-marked. However, in Icelandic, PRO appears to be case-marked, and is thus governed.[6] More recent research attempts to characterize PRO without reference to the PRO theorem.[3]

Null case of PRO

[edit]It has been argued that PRO has case, which is checked by non-finite T.[7] This is illustrated by the contrasting examples in (7), (8) and (9) below. The (a) examples show contexts where an overt DP subject is ungrammatical in the specifier position of the TP (tense phrase). The (b) examples shows that, in exactly the same contexts, a null PRO subject is grammatical.[4]

(7) a. *Kerry attempted [Bill [T to] study physics].

b. Kerryi attempted [PROi [T to] study physics].

(8) a. *Kerry persuaded Sarah [Bill [T to] study physics].

b. Kerry persuaded Sarahj [PROj [T to] study physics].

(9) a. *It is not easy [Bill [T to] study physics].

b. It is not easy [PROk [T to] study physics].

(adapted from Martin 2001: 144 (13))

|

The subject of the non-finite T must satisfy the case checked by T, and this case cannot be satisfied by a pronounced (i.e., overt) DP, it is argued that these non-finite T's (and -ing clausal gerunds), check for a special null case (assigned in English by infinitival to),[8] and that the only DP compatible with such a case is PRO.[4]

The following tree diagrams for (7b), (8b), and (9b) show how PRO can be co-indexed with the different types of antecedents: the tree diagram for (7a) shows subject control; the tree for (8b) shows object control; the tree for (9b) shows PRO with arbitrary reference.

|

|

|

It is furthermore argued that null case is the only case assignable to PRO, and that PRO is the only DP to which null case may be assigned.[4] These assertions have since been challenged by certain data which appear to demonstrate that PRO may carry case other than null case.[9]

Distribution of PRO

[edit]The distribution of PRO is constrained by the following factors:

- PRO can only be the subject of a non-finite clause

- PRO can be controlled by a subject or object antecedent

- PRO can lack an antecedent, i.e. be uncontrolled[10]

- PRO may undergo movement

PRO as subject of non-finite clause

[edit]The examples in (10) show that PRO is grammatical as the subject of non-finite clauses. In both (10a) and (10b), PRO is the subject of the non-finite clause to study physics. In (10a), the antecedent of PRO is the matrix subject Kerry, and in (10b) it is the matrix object Sarah. The examples in (11) show that PRO is ungrammatical in finite clauses and in non-subject position: (11a) establishes that PRO cannot be the subject of a finite clause, and (11b-c) establish that PRO cannot occur in complement position. In particular, (11b) shows that PRO cannot be complement to V, while (11c) shows that PRO cannot be complement to P.[4]

(10) a. Kerryi attempted PROi to study physics.

b. Kerry persuaded Sarahj PROj to study physics.

(11) a. *Pam believes PRO solved the problem.

b. *Sarah saw PRO.

c. *Sarah saw pictures of PRO.

(Martin 2001: 141)

|

Obligatory control of PRO

[edit]In contexts where PRO is obligatorily controlled, the following restrictions hold:[10]

- PRO must have an antecedent (12a);

- the antecedent for PRO must be local (12b);

- PRO must be c-commanded by the antecedent (12c);

- under VP ellipsis, PRO can only be construed with a sloppy (bound variable) reading: in (12d) Bill expects himself (Bill) to win (the reading where Bill expects John to win is excluded);

- obligatorily controlled PRO may not have split antecedents,(12e).

(12) a. *It was expected PRO to shave himself.

b. *John thinks that it was expected PRO to shave himself.

c. *John’s campaign expects PRO to shave himself.

d. John expects PRO to win and Bill does too. (= Bill expects Bill to win)

e. *Johni told Maryj PROi+j to wash themselves/each other.

(Hornstein 1999: 73)

|

Non-obligatory control of PRO

[edit]In contexts where PRO is not obligatorily controlled, as in (13a), then when PRO does have an antecedent, the following restrictions hold:[10]

- the antecedent need not be local, (13b);

- the antecedent need not c-command PRO,(13c);

- with VP-ellipsis, both sloppy and strict readings are permitted: in (13d), Bill may think that John having his resume in order is crucial, or that Bill may that having his own resume in order is crucial (Need fixation, Ala Al-Kajela 2015 PRO Theory, Norbert Hornstein 1999 Movement and Control claims NOC only allows strict interpretation with VP ellipsis.)

- under non-obligatory control, PRO allows split antecedents, (13e)

(13) a. It was believed that PRO shaving was important.

b. Johni thinks that it is believed that PROi shaving himself is important.

c. Clinton’si campaign believes that PROi keeping his sex life under control is necessary for electoral success.

d. John thinks that PRO getting his resume in order is crucial and Bill does too.

e. Johni told Maryj [that [[PROi+j washing themselves/each other] would be fun]].

(Hornstein 1999: 73)

|

Movement of PRO

[edit]

For a sentence such as (14a), there is a debate about whether PRO moves from Spec-VP (where it is introduced) to Spec-TP in non-finite clauses. Baltin (1995) argues that the tense marker to does not have an EPP feature, and that therefore PRO does not move to Spec-TP; this yields the structure in (14b).[11] In contrast, Radford (2004) argues that infinitival to does have an EPP feature, and that therefore PRO must move to Spec-TP, as in (14c).[3]

(14) a. They don't want [to see you]

b. They don't want [CP [C ∅] [TP [T to] [VP PRO [V see] you]]]

c. They don't want [CP [C ∅] [TP PRO [T to] [VP

|

Baltin argues against moving PRO to Spec-TP on this basis of so-called wanna contraction, illustrated in (15): placing PRO between want and to would block the contraction of want+to into wanna.[11] Radford argues that an analysis that assigns an EPP feature to infinitival to (and so forces movement of PRO to Spec-TP), can still account for wanna: the latter can be achieved by having to cliticise onto the null complementizer ∅, and then having this [C-T] compound cliticise onto want.[3]

(15) They don't wanna see you. |

Radford justifies moving PRO to Spec-TP on the basis of the binding properties of certain sentences. For example, in (16), moving PRO to Spec-TP is necessary for it to c-command themselves, which in turn is necessary to satisfy the binding principles and have PRO be coreferenced with themselves.[3]

(16) a. "to themselves be indicted"

b. [CP [C ∅] [TP [T to] [AUXP themselves [AUX be] [VP [V indicted] PRO]]]]

c. [CP [C ∅] [TP PRO [T to] [AUXP themselves [AUX be] [VP [V indicted]

|

Cross-linguistic differences in PRO

[edit]Occurrences of PRO have been discussed and documented with regards to many languages. Major points of similarities and differences center on the following:

- whether PRO lacks case (e.g., English)

- whether PRO has case (e.g., Icelandic)

- whether experiencer arguments can control PRO in adjunct clauses (e.g., Romance languages)

English PRO is caseless

[edit]In English, PRO is treated as caseless, and can be controlled by the subject (17a) or object (17b) of the verb in the main clause) or it may be uncontrolled (17c).[12]

(17) a. Johnj promised Mary [PROj to control himself]

b. John convinced Billk [PROk to sleep]

c. [PRO to know her] is [PRO to love her].

((a) & (b) from Koopman, Sportiche and Stabler, 2014: 247 (30), 251 (47))

|

In (17a) above, the subject of the verb in the main clause (John promised Mary) is John, so PRO is interpreted as referring to John, while in (17b) to sleep is an action performed by Bill, and PRO is interpreted as referring to Bill. And in (17c), PRO is not controlled by any antecedent, and so can be paraphrased as 'For someone to love her is for someone to know her'; this is called impersonal PRO or arbitrary PRO.

Icelandic PRO is case-marked

[edit]Icelandic PRO appears to be case-marked.[9] Rules of case agreement in Icelandic require that floated quantifiers agree in case (as well as in number and gender) with the DP they quantify. As illustrated in (18) and (19), this agreement requirement holds of PRO. In (18), the quantifier báðir 'both' appears in the nominative masculine plural form. In (19), the quantifier báðum 'both' appears in the dative plural form. The occurrence of such forms indicates that the quantifiers are agreeing with their antecedent, namely PRO. This leads to the conclusion that PRO must be case-marked, and this is possible only if PRO is in Spec-TP.

Bræðrunum

brothers.the.D.M.PL

likaði

liked

illa

ill

[að

to

PRO

N

vera

be

ekki

not

báðir

both.N.M.PL

kosnir].

elected

'The brothers disliked not being both elected.'

Bræðurnir

brothers.the.N.M.PL

æsktu

wished(for)

þess

it

[að

to

PRO

D

vera

be

báðum

both.D.PL

boðið].

invited

'The brothers wished to be both invited.' (Sigurðsson and Sigursson, 2008: 410 (18))

Romance PRO controlled by Dative experiencer

[edit]PRO in adjunct clauses in Spanish can be controlled by dative experiencer subjects. In (20), the verb saber 'know' introduces the dative experiencer subject Juan, and this DP controls the PRO in the phrase sin PRO saber por qué. (Dative experiencers (see Theta role) were also very common in Old English.[13])

[Sin

without

PROi

saber

to.know

por qué]

why

A

to

Juani

Juan.DAT

le

3S.DAT

gusta

likes

María.

María.NOM

'Without knowing why, Juan likes María.' (Montrul 1998: 32 (12))

In French, PRO can be controlled by dative experiencers in object position in an adjunct clause. (This is also true for Spanish.) In (21), the dative experiencer object Pierre controls the PRO-subject of the adjunct clause avant même de PRO y avoir été initié 'before even having been initiated to it'.

Le

the

parachutisme

skydiving

effraye

scares

Pierrei

Pierre

[avant

before

même

even

de

of

PROi

y

LOC

avoir

to.have

été

been

initié].

initiated

'Skydiving scares Peteri [even before PROi being initiated to it].' (Montrul 1998: 33 (13))

The structure of sentences like (21) can lead to an ambiguous interpretation if the subject is animate.[13] This illustrated in (26), where the PRO in the adjunct clause can be controlled by either the subject (22a) or the object (22b) of the main clause.

Améliei

Amelie

effraye

scares

les

the

étudiants

students

avant

before

même

even

de

of

PROi

les

them

rencontrer.

to.meet

'Ameliei scares the students [even before PROi^meeting them].'

Amélie

Amelie

effraye

scares

[les

the

étudiants]j

students

avant

before

même

even

de

of

PROj

la

her

rencontrer.

to.meet

'Amelie scares the studentsi [even before PROj^meeting her].'

Alternative theories

[edit]A movement theory of control

[edit]Norbert Hornstein has proposed that control verbs can be explained without resorting to PRO, and as such that PRO can be done away with entirely. This theory explains obligatory control with movement, and non-obligatory control with pro (little pro). This alternative theory of control is in part motivated by adherence to the minimalist program.[10]

Working assumptions

[edit]The movement theory of control is predicated on the following principles.[10]

(23) a. θ-roles are features on verbs.

b. A DP/NP "receives" a θ-role by checking a θ-feature of a verbal/predicative phrase that it merges with.

c. There is no upper bound on the number of θ-roles a chain can have.

d. Sideward movement is permitted.

(Hornstein 1999: 78)

|

The idea introduced in (23d) is of particular importance as a single DP/NP-chain can acquire more than one θ-role by simultaneously satisfying the θ-criterion across multiple positions, e.g. the subject of the non-finite embedded clause and the subject of the matrix verb.[10] In this context a chain refers to an argument which has moved and all of its traces.[3] Hornstein argues that there is insufficient empirical evidence that a chain must be restricted to a single θ-role and that allowing multiple θ-roles per chain is the null hypothesis.[10]

Obligatory control as movement

[edit]These principles allow control verbs to be explained by movement and what had previously been analyzed as PRO is instead treated as the trace of DP/NP-movement. Consider the example in (24): to derive (24a) the DP John moves through several positions, and checks a θ-role at each landing site; this is shown in (24b). In this way, the chain of Johns satisfies the Agent θ-role of the verb hope, as well as the Agent θ-role of the verb leave. In the movement analysis, multiple θ-role assignment does the same work as allowing obligatory control of a PRO subject.[10]

(24) a. John hopes to leave.

b. [IP John [VP John [hopes [IP John to [VP John leave]]]]]

(Hornstein 1999: 79)

|

Non-obligatory control as pro

[edit]With the need for PRO eliminated under obligatory control, Hornstein argues that it follows naturally that PRO should be altogether eliminated from the theory as it is equivalent to little pro. In particular, little pro is equivalent to an indefinite or a definite pronoun (similar to English one) and has the same distribution as non-obligatory control PRO. With non-obligatory control, an overt embedded subject may be introduced (25) or omitted (26), and omitting the embedded subject may result in an arbitrary reading. Additionally, the overt subject may not be moved out of the embedded clause, (27).[10]

(25) a. It is believed that Bill’s shaving is important.

b. It is impossible for Bill to win at roulette.

(26) a. It is believed that pro shaving is important.

b. It is impossible pro to win at roulette.

(27) a. *Bill’s is believed that shaving is important.

b. *Bill is impossible to win at roulette.

(adapted from Hornstein 1999: 92)

|

In addition, non-obligatory control and movement are in complementary distribution. Since non-obligatory control occurs when movement is not permitted, it may be treated as an elsewhere case: little pro inserted as a last resort measure to rescue the derivation if an overt subject is missing.[10]

Criticism

[edit]Since the publication of this movement theory of control some data has been discussed which it does not explain, challenging the completeness of the movement theory of control.[14]

- Imoaka argues that scrambling out of a split control clause is incompatible with the movement theory of control as constructed in Japanese[14] by Takano[15] and Fujii.[16] Imoaka argues for a theory of Equi-NP Deletion to explain control and claims that such a theory is empirically superior as it successfully explains the problematic data as well as the data previously explained by the movement theory of control.[14]

Abbreviation keys

[edit]Morpheme gloss key

[edit]| Abbreviation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| A | Accusative |

| D or dat | Dative |

| DFT or dft | Default |

| F | Feminine |

| M | Masculine |

| N or nom | Nominative |

| PL | Plural |

| SG | Singular |

Syntactic abbreviation key

[edit]| Abbreviation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| IP | Inflectional phrase |

| DP | Determiner phrase |

| NP | Noun phrase |

| CP | Complementizer phrase |

| TP | Tense phrase |

| VP | Verb phrase |

| AUXP | Auxiliary verb phrase |

| NegP | Negation Phrase |

| AjP | Adjective Phrase |

Tree diagram key

[edit]| Abbreviation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Ø | empty category |

| Øpast | past tense marker |

| Øpres | present tense marker |

| Ø(WORD) | indicates movement of WORD |

(See Syntactic abbreviation key for more information.)

Note: Both the tense marker (under Ts) and the tensed verb (under Vs) are added in the syntactic tree diagrams for readability, although only one would be shown in an average tree diagram. That is, the verbs in these trees would be in the infinitival form if the tense (T) is shown, and is not empty (Ø). Also, movement of determiner phrases has only been illustrated when it is relevant, as in Tree Diagram (10).

See also

[edit]- Control (linguistics)

- Pronoun

- Binding (linguistics)

- Empty category

- Non-finite clauses

- Determiner phrase

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 9781405100175.

- ^ a b Chomsky, Noam (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding: The Pisa Lectures. Mouton de Gruyter.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Radford, Andrew (2004). Minimalist Syntax: Exploring the structure of English. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c d e Roger, Martin (2001). "Null Case and the Distribution of PRO". Linguistic Inquiry. 1. 32 (1): 141–166. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.569.2341. doi:10.1162/002438901554612. JSTOR 4179140. S2CID 30326385.

- ^ a b c d Camacho, José A. (2013). Null Subjects. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107034105.

- ^ a b Sigurðsson, Halldór (1991). "Icelandic case-marked PRO and the licensing of lexical arguments" (PDF). Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 2. 9 (2): 327–364. doi:10.1007/bf00134679. S2CID 189901798.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam; Lasnik, Howard (1993). The theory of principles and parameters. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- ^ Baltin, Mark; Barrett, Leslie. "The Null Content of Null Case" (PDF). NYU Department of Linguistics. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ^ a b Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann; Sigursson, Halldór Ármann (2008). "The Case of PRO". Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 2. 26 (2): 403–450. doi:10.1007/s11049-008-9040-6. JSTOR 20533009. S2CID 55126035.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hornstein, Norbert (1999). "Movement and Control". Linguistic Inquiry. 1. 30 (1): 69–96. doi:10.1162/002438999553968. JSTOR 4179050. S2CID 593044.

- ^ a b Baltin, Mark (1995). "Floating Quantifiers, PRO and predication". Linguistic Inquiry. 1. 26: 199–248.

- ^ Koopman, Hilda; Sportiche, Dominique; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory. p. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0016-8.

- ^ a b Montrul, Silvina A. (1998). "The L2 acquisition of dative experiencer subjects". Second Language Research. 14 (1): 27–61. doi:10.1191/026765898668810271. S2CID 145668459.

- ^ a b c Imoaka, Ako (2011). "Scrambling out of a control clause in Japanese: An argument against the Movement Theory of Control". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 17 (1). Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ Takano, Yuji (2009). "Scrambling and the nature of movement" (PDF). Nanzan Linguistics. 1. 5: 75–104. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Fujii, Tomohiro (2006). Some theoretical issues in Japanese control (PDF) (Ph.D.). University of Maryland. Retrieved 30 October 2014.